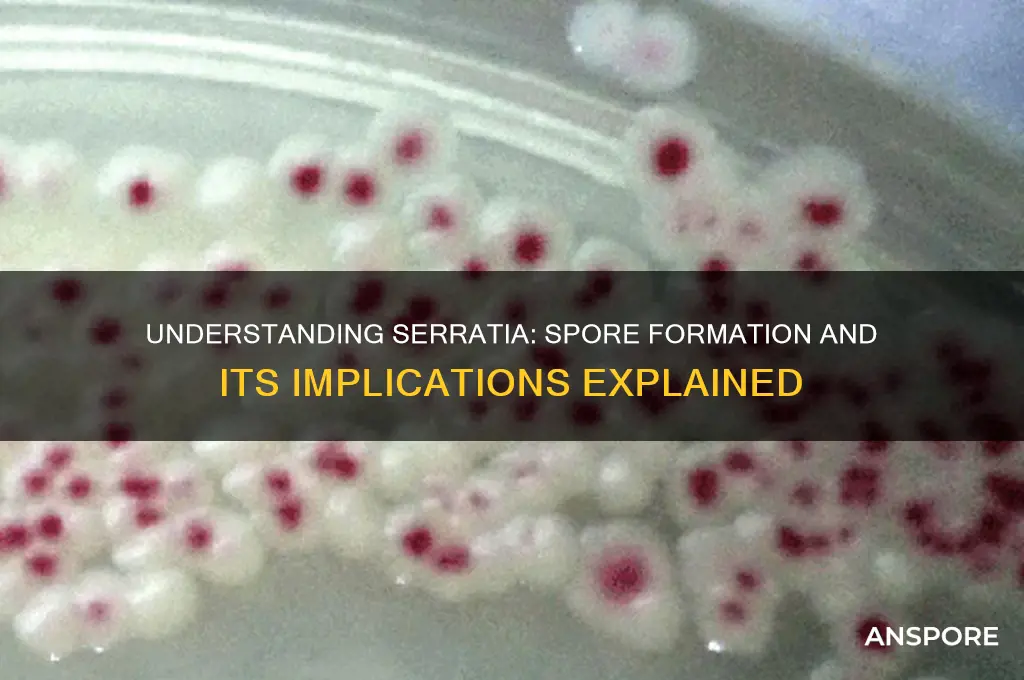

*Serratia marcescens*, a Gram-negative bacterium commonly found in environmental and clinical settings, is often associated with questions about its spore-forming capabilities. Unlike well-known spore-formers such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, *Serratia* does not produce spores under normal conditions. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow some bacteria to survive harsh environments, but *Serratia* relies on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance, to endure adverse conditions. While there have been rare reports of *Serratia* exhibiting spore-like structures under specific laboratory conditions, these are not considered true spores and are not a characteristic feature of the species. Understanding *Serratia*'s lack of spore formation is crucial for effective infection control and treatment strategies in healthcare and industrial settings.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | No, Serratia species are non-spore forming bacteria. |

| Gram Stain | Negative |

| Morphology | Rod-shaped (bacilli) |

| Motility | Most strains are motile by peritrichous flagella |

| Oxygen Requirement | Facultative anaerobe |

| Optimal Growth Temperature | 35-37°C |

| Habitat | Found in various environments including soil, water, plants, and animals |

| Pathogenicity | Opportunistic pathogen in humans, causing infections like pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and wound infections |

| Biochemical Test | Positive for citrate utilization, negative for oxidase |

| Pigmentation | Many strains produce red pigment (prodigiosin) |

What You'll Learn

Conditions for Spore Formation

Spore formation in bacteria is a survival mechanism triggered by harsh environmental conditions. For *Serratia*, a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, the question of spore formation is nuanced. Unlike well-known spore-formers such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, *Serratia* species are not typically classified as spore-forming. However, understanding the conditions that generally induce spore formation in bacteria provides insight into why *Serratia* may or may not exhibit this behavior. Nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources, is a primary trigger for spore formation in other bacteria. When resources become scarce, cells initiate a complex genetic program to form spores, ensuring long-term survival in adverse conditions.

Temperature and pH extremes also play a critical role in inducing spore formation. For spore-forming bacteria, temperatures above their optimal growth range (often around 37°C) can signal environmental stress, prompting the sporulation process. Similarly, pH levels outside the neutral range (pH 7) can activate stress responses. While *Serratia* does not form spores, it may employ other survival strategies, such as biofilm formation or metabolic shifts, under similar stress conditions. For instance, *Serratia marcescens* is known to produce pigments like prodigiosin, which may serve protective functions in stressful environments.

The presence or absence of oxygen is another factor influencing spore formation in bacteria. Anaerobic conditions often trigger sporulation in obligate anaerobes like *Clostridium*, as oxygen deprivation signals a hostile environment. In contrast, *Serratia* species are facultative anaerobes, capable of surviving in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions without resorting to spore formation. This adaptability highlights the diversity of bacterial survival mechanisms and underscores why *Serratia* does not rely on sporulation.

Practical considerations for preventing *Serratia* contamination in clinical or industrial settings involve controlling these environmental factors. Maintaining optimal nutrient levels, temperature, and pH can discourage stress responses that might otherwise lead to survival mechanisms. For example, in healthcare settings, proper disinfection protocols and temperature control (e.g., storing materials below 4°C or above 60°C) can inhibit *Serratia* growth. Additionally, monitoring oxygen levels in closed systems, such as water distribution networks, can reduce the risk of *Serratia* proliferation, as it thrives in environments with organic matter and moisture.

In summary, while *Serratia* is not spore-forming, the conditions that induce spore formation in other bacteria—nutrient deprivation, temperature and pH extremes, and oxygen availability—offer valuable insights into *Serratia*'s survival strategies. By understanding these triggers, we can design targeted interventions to control *Serratia* in various environments. This knowledge is particularly relevant in healthcare, where *Serratia* is an emerging nosocomial pathogen, and in industries where contamination can lead to significant economic losses.

Can Bacterial Cells Form Multiple Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process in Serratia

Serratia, a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, has long been a subject of interest in microbiology due to its versatility and adaptability. While many bacteria within the family Enterobacteriaceae are known for their ability to form spores under stress, Serratia species are generally considered non-spore-forming. However, recent studies have shed light on a unique sporulation-like process in certain Serratia strains, particularly under specific environmental conditions. This process, though not true sporulation, involves the formation of highly resistant cells that resemble spores in their ability to withstand harsh conditions. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for fields such as biotechnology, medicine, and environmental science.

The sporulation-like process in Serratia is triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources. Under these conditions, some strains undergo morphological changes, including cell wall thickening and the accumulation of storage compounds. These changes enhance the cell’s ability to survive in adverse environments, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to antimicrobials. For instance, Serratia marcescens, a well-studied species, has been observed to form these resistant cells when cultured in minimal media with limited nutrients. Researchers have noted that this process is not as robust or widespread as true sporulation in bacteria like Bacillus subtilis, but it highlights Serratia’s remarkable survival strategies.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this sporulation-like process has significant implications. In clinical settings, Serratia species are known to cause opportunistic infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients. The formation of resistant cells could contribute to the persistence of these bacteria in hospital environments, making them difficult to eradicate. For example, Serratia has been isolated from medical devices and surfaces, where it can survive for extended periods. To mitigate this, healthcare facilities should implement rigorous disinfection protocols, including the use of spore-killing agents like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine-based cleaners, even though Serratia does not form true spores.

Comparatively, the sporulation-like process in Serratia differs from true sporulation in several key aspects. True spores, such as those formed by Bacillus or Clostridium species, are highly resistant, metabolically dormant structures that can survive for years. In contrast, Serratia’s resistant cells retain some metabolic activity and are less durable. However, this distinction does not diminish their importance. For instance, in biotechnology, Serratia’s ability to produce pigments and enzymes could be enhanced by exploiting this process to improve cell survival during industrial applications. Researchers are exploring ways to manipulate these conditions to optimize production yields.

In conclusion, while Serratia is not traditionally classified as a spore-forming bacterium, its sporulation-like process under stress conditions is a fascinating adaptation. This mechanism enhances its survival in challenging environments, with implications for both clinical and industrial settings. By studying this process, scientists can develop more effective strategies to control Serratia infections and harness its biotechnological potential. Whether in a hospital or a laboratory, understanding this unique feature of Serratia opens new avenues for research and practical applications.

Mastering Continuous Growth: Effective Strategies to Source and Cultivate Spores

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers for Spores

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are not inherently active. They lie dormant, biding their time until environmental conditions signal it's safe to germinate. Understanding these triggers is crucial for controlling spore-forming organisms like *Serratia*, a genus of bacteria with species capable of forming spores under specific circumstances.

While *Serratia marcescens*, a common human pathogen, is not typically considered spore-forming, some strains within the genus possess this ability. This highlights the importance of identifying the environmental cues that awaken dormant spores, regardless of the specific species.

The Awakening: Key Environmental Triggers

- Nutrient Availability: Spores are metabolically inactive, conserving energy until nutrients become available. A sudden influx of organic matter, such as amino acids, sugars, or vitamins, can act as a powerful wake-up call, triggering germination. This is why spores can persist in seemingly inhospitable environments like soil or dust, waiting for a nutrient-rich opportunity to arise.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Many spore-forming organisms have evolved to recognize specific temperature ranges as signals for germination. For example, some Bacillus species, close relatives of Serratia, germinate optimally at temperatures between 25°C and 37°C (77°F - 98.6°F). Understanding these temperature preferences is crucial for controlling spore growth in food processing, healthcare settings, and other environments.

- pH Shifts: Changes in pH can also trigger spore germination. Some spores prefer neutral pH, while others thrive in acidic or alkaline conditions. Clostridium botulinum, a notorious spore-former responsible for botulism, germinates best in slightly acidic environments, highlighting the importance of pH control in food preservation.

- Hydration: Water is essential for spore germination. Even a small amount of moisture can activate dormant spores, making humidity control critical in preventing spore-related issues. This is why desiccation is a common method for spore preservation and why dry environments are less conducive to spore growth.

Practical Implications:

Understanding these environmental triggers allows us to develop strategies to control spore-forming organisms. In healthcare settings, rigorous cleaning and disinfection protocols, coupled with humidity control, can minimize the risk of *Serratia* and other spore-forming pathogens. In food production, careful monitoring of temperature, pH, and moisture levels during processing and storage is essential to prevent spoilage and foodborne illness.

By recognizing the specific needs of spores and manipulating their environment, we can effectively manage these resilient organisms and protect human health and safety.

Unveiling the Microscopic World: Bacillus Spore Size Explained

You may want to see also

Spore Resistance Mechanisms

Observation: *Serratia marcescens*, a Gram-negative bacterium, is not typically classified as spore-forming, yet it exhibits remarkable resistance mechanisms that rival those of spore-forming organisms. This raises the question: How does *Serratia* survive harsh conditions without spores, and what can we learn from its resistance strategies?

Analytical Insight: Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, which encapsulate their DNA in a protective spore coat, *Serratia* relies on biofilm formation and efflux pumps to withstand environmental stressors. Biofilms, extracellular matrices composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA, act as a physical barrier against antimicrobials and desiccation. Efflux pumps, such as the AcrAB-TolC system, expel toxic compounds like antibiotics and disinfectants, ensuring cellular survival. These mechanisms collectively contribute to *Serratia*'s persistence in hospital environments, where it is a notorious nosocomial pathogen.

Instructive Guidance: To combat *Serratia*'s resistance, healthcare facilities should implement targeted disinfection protocols. Quaternary ammonium compounds (QUATs) are commonly used but can be neutralized by biofilms. Instead, alternating between QUATs and chlorine-based disinfectants (e.g., 1,000 ppm hypochlorite solution) disrupts biofilm integrity. For antibiotic treatment, combination therapy—such as cefepime (2 g IV every 8 hours) paired with levofloxacin (750 mg IV daily)—can bypass efflux pump mechanisms. Always verify local resistance patterns before prescribing.

Comparative Perspective: While *Serratia* lacks spores, its resistance mechanisms share similarities with spore-forming bacteria. For instance, both employ DNA repair enzymes to counteract oxidative stress, a common environmental threat. However, *Serratia*'s reliance on biofilms and efflux pumps offers a dynamic, non-spore alternative to survival. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptability of bacteria in the absence of spore formation, underscoring the need for multifaceted control strategies.

Practical Takeaway: Understanding *Serratia*'s resistance mechanisms is crucial for infection control. Regularly audit disinfection practices, rotate antimicrobial agents, and monitor biofilm hotspots like sinks and medical devices. For at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised patients), implement contact precautions and isolate colonized individuals. By targeting biofilms and efflux pumps, we can mitigate *Serratia*'s resilience, even without the challenge of spores.

Mastering Multiple Personalities in Spore: A Creative Guide to Split Traits

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance of Spores

Spores, the dormant survival forms of certain bacteria, pose unique challenges in clinical settings due to their resilience and ability to withstand harsh conditions. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to disinfectants, making them a persistent threat in healthcare environments. For instance, *Clostridioides difficile*, a spore-forming pathogen, is a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections, particularly in patients over 65 years old or those on prolonged antibiotic therapy. Understanding the clinical significance of spores is critical for infection prevention and control.

The ability of spores to remain viable on surfaces for months underscores the importance of rigorous disinfection protocols. Standard alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against vegetative bacteria, are ineffective against spores. Instead, healthcare facilities must rely on spore-specific disinfectants, such as chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 5,000–10,000 ppm hypochlorite), to decontaminate surfaces and medical equipment. Failure to implement these measures can lead to outbreaks, particularly in high-risk areas like intensive care units and surgical wards.

From a diagnostic perspective, identifying spore-forming bacteria requires specific laboratory techniques. Microscopic examination using Gram staining and spore-specific stains, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, can differentiate spores from vegetative cells. Additionally, molecular methods like PCR can rapidly detect spore-forming pathogens, aiding in timely treatment decisions. For example, early detection of *Bacillus anthracis* spores in bioterrorism scenarios is crucial for initiating antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 60 days) and preventing systemic infection.

Clinically, spore-forming bacteria often necessitate targeted antimicrobial therapy. While many spores are inherently resistant to antibiotics, the germinated vegetative form is susceptible. For *C. difficile* infections, fidaxomicin (200 mg twice daily for 10 days) or vancomycin (125 mg four times daily for 10–14 days) are first-line treatments, depending on infection severity. Probiotics containing *Sporolactobacillus* strains may also be considered to restore gut microbiota balance, though evidence is still emerging.

Finally, patient education plays a pivotal role in managing spore-related infections. Emphasizing hand hygiene with soap and water, rather than alcohol-based sanitizers, is essential for breaking the chain of transmission. Patients should also be advised to avoid unnecessary antibiotic use, as disruption of normal flora increases susceptibility to spore-forming pathogens. By integrating these clinical strategies, healthcare providers can mitigate the risks associated with spores and improve patient outcomes.

Do Nano Spores Drop from Infected Enemies? A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Serratia is not a spore-forming bacterium. It is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that does not produce spores.

Yes, Serratia can survive in various environments due to its ability to form biofilms and adapt to different conditions, but it does not rely on spore formation for survival.

No, none of the known species within the Serratia genus are capable of forming spores.

Serratia lacks the genetic and physiological mechanisms required for spore formation, unlike Bacillus, which forms highly resistant endospores.

While Serratia is not spore-forming, it can still be resistant to certain disinfectants due to its biofilm formation and other adaptive mechanisms, but it is generally more susceptible than spore-forming bacteria.