Spores are a crucial part of the life cycle of many organisms, particularly in plants, fungi, and some protists. Understanding whether spores are haploid or diploid is essential for grasping their role in reproduction and development. In general, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. This is particularly true for spores produced during the alternation of generations in plants, such as ferns and mosses, where haploid spores germinate into gametophytes. However, in some organisms like fungi, spores can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the stage of their life cycle. For instance, in basidiomycetes, diploid spores (basidiospores) are produced after karyogamy, while in ascomycetes, haploid ascospores are formed following meiosis. Thus, the ploidy of spores varies across different groups of organisms, reflecting their diverse reproductive strategies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nature of Spores | Spores can be either haploid or diploid depending on the organism and life cycle stage. |

| Haploid Spores | Produced in haploid organisms (e.g., fungi, plants during alternation of generations) via meiosis; contain a single set of chromosomes. |

| Diploid Spores | Produced in diploid organisms or during specific life cycle stages (e.g., some fungi, algae); contain two sets of chromosomes. |

| Function in Fungi | Haploid spores (e.g., conidia, spores) are common in asexual reproduction; diploid spores (e.g., zygospores) form after sexual reproduction. |

| Function in Plants | Haploid spores (e.g., pollen, spores from sporangia) are part of the alternation of generations; diploid spores are rare in plants. |

| Examples of Haploid Spores | Fungal spores (e.g., Aspergillus), plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses). |

| Examples of Diploid Spores | Zygospores in fungi (e.g., Rhizopus), some algal spores. |

| Role in Life Cycle | Haploid spores germinate into haploid individuals; diploid spores germinate into diploid individuals or undergo meiosis. |

| Chromosome Count | Haploid (n): 1 set; Diploid (2n): 2 sets. |

| Reproductive Mode | Haploid spores often asexual; diploid spores often result from sexual reproduction. |

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive cells capable of developing into new organisms without fertilization

- Haploid vs. Diploid: Haploid spores have one set of chromosomes; diploid cells have two sets

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis in the life cycle

- Spores in Plants: Plant spores (e.g., ferns) are typically haploid, part of alternation of generations

- Spores in Bacteria: Bacterial spores are diploid, formed for survival, not reproduction

Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive cells capable of developing into new organisms without fertilization

Spores are a fascinating example of nature’s efficiency in reproduction, serving as self-contained units capable of developing into new organisms without the need for fertilization. This asexual method of reproduction is a hallmark of plants, fungi, and certain protozoans, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments. Unlike seeds, which require a combination of male and female gametes, spores are produced by a single parent and carry the genetic material necessary for growth. This independence from fertilization makes spores a critical survival mechanism, particularly in harsh or unpredictable conditions.

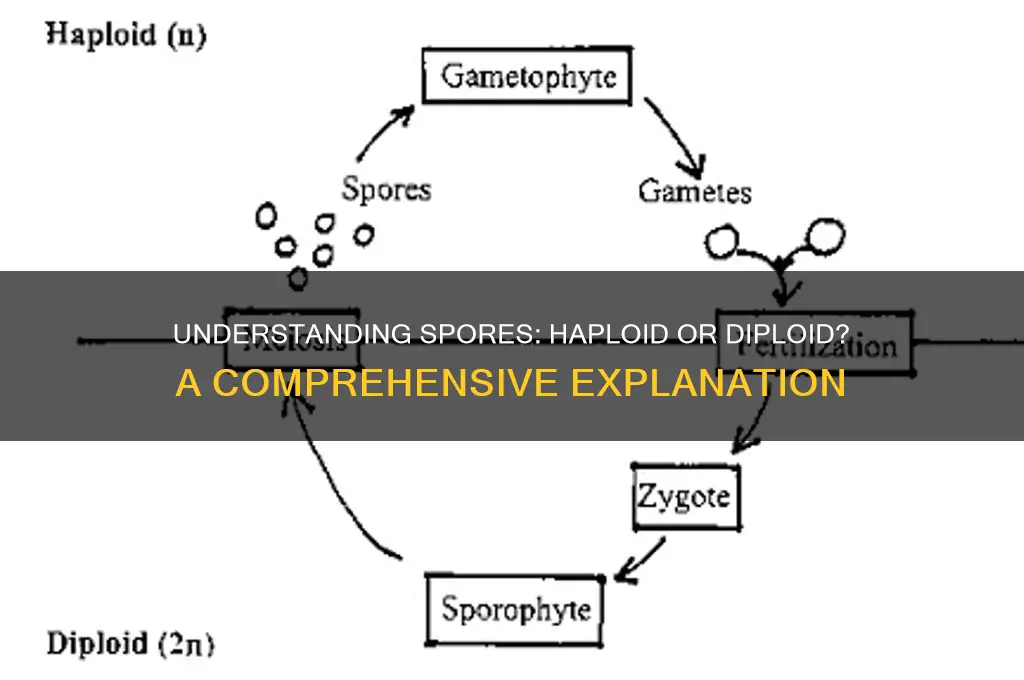

To understand whether spores are haploid or diploid, it’s essential to examine their life cycles. In fungi, for instance, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. These haploid spores germinate and grow into haploid individuals, which then produce gametes through mitosis. When two compatible gametes fuse, they form a diploid zygote, which develops into a structure that eventually releases new haploid spores. This alternation between haploid and diploid phases, known as the alternation of generations, is a defining feature of many spore-producing organisms.

In contrast, some plants, like ferns, produce both haploid and diploid spores during their life cycles. Haploid spores grow into gametophytes, which produce gametes. After fertilization, a diploid sporophyte develops, which in turn produces diploid spores. This complexity highlights the versatility of spores as reproductive structures, adapting to the needs of different organisms. For practical purposes, gardeners and farmers can exploit this knowledge by controlling spore dispersal to manage plant populations or prevent fungal infections.

The haploid nature of most spores has significant evolutionary advantages. Haploid organisms can rapidly adapt to changing environments because mutations in their single set of chromosomes are immediately expressed. This allows spore-producing species to colonize new habitats quickly and efficiently. For example, mold spores can survive in extreme conditions, only to germinate when resources become available. Understanding this adaptability can inform strategies for pest control or conservation efforts, particularly in ecosystems where spore-producing organisms dominate.

In summary, spores are reproductive cells that bypass the need for fertilization, embodying a streamlined approach to survival and proliferation. Whether haploid or diploid, their role in the life cycles of fungi, plants, and protozoans underscores their importance in biology. By studying spores, we gain insights into the mechanisms of asexual reproduction and the resilience of life in diverse environments. This knowledge is not only academically valuable but also has practical applications in agriculture, medicine, and ecology.

Zygosporangium Spore Production: Understanding the Quantity per Structure

You may want to see also

Haploid vs. Diploid: Haploid spores have one set of chromosomes; diploid cells have two sets

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction in many organisms, are fundamentally haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. This characteristic is crucial for their role in the life cycles of plants, fungi, and some protists. Haploid spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring genetic diversity. For example, in ferns, spores develop into gametophytes, which are haploid plants that produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. This haploid phase is essential for the alternation of generations, a life cycle pattern where organisms alternate between haploid and diploid stages.

In contrast, diploid cells, which contain two sets of chromosomes, are prevalent in the somatic cells of multicellular organisms. Diploid cells arise from fertilization, where a haploid sperm fuses with a haploid egg, restoring the full chromosome complement. While spores are inherently haploid, diploid cells are not involved in the dispersal or survival strategies that spores excel at. For instance, in humans, diploid cells make up the majority of the body’s tissues, ensuring stability and functionality through consistent genetic information. Understanding this distinction is key to grasping the reproductive strategies of different organisms.

The haploid nature of spores confers unique advantages, particularly in harsh environments. Haploid organisms can reproduce asexually through spore formation, allowing rapid colonization of new habitats. For example, fungal spores can survive extreme conditions such as drought or heat, dispersing widely until they find suitable conditions to germinate. This resilience is a direct result of their haploid state, which simplifies their genetic makeup and reduces the energy required for reproduction. Diploid cells, while stable, lack this adaptability, as they rely on complex mechanisms for survival and reproduction.

From a practical standpoint, the haploid-diploid distinction has significant implications in agriculture and biotechnology. Haploid plants, often induced artificially, are valuable for breeding programs because they allow for faster trait selection. For instance, haploid wheat or maize plants can be doubled to create homozygous diploid lines, reducing the time needed to develop new varieties. Conversely, diploid cells are essential for genetic engineering, as they provide a stable platform for introducing and expressing new traits. Recognizing the roles of haploid spores and diploid cells enables scientists to harness their unique properties for innovation.

In summary, the difference between haploid spores and diploid cells lies in their chromosome number and functional roles. Haploid spores, with their single set of chromosomes, are specialized for dispersal, survival, and asexual reproduction, making them vital in the life cycles of many organisms. Diploid cells, with two sets of chromosomes, form the basis of somatic tissues and are crucial for stability and complex development. By understanding this distinction, we can appreciate the diverse strategies organisms employ to thrive and adapt in their environments.

Can You Safely Eat Food After Removing Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis in the life cycle

Fungal spores, the microscopic units of dispersal and survival, are predominantly haploid, a characteristic that plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of fungi. This haploid nature is a direct result of their production through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring genetic diversity. In fungi, this process occurs within specialized structures like sporangia or asci, where diploid cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. For instance, in the common bread mold *Rhizopus*, the sporangia release thousands of haploid spores, each capable of developing into a new individual under favorable conditions.

Understanding the haploid nature of fungal spores is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications. Haploid spores simplify genetic studies, as they carry a single set of chromosomes, making it easier to track traits and mutations. This is particularly useful in biotechnology, where fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* are engineered for producing antibiotics and enzymes. For example, the haploid spores of *Penicillium chrysogenum* are used to study and enhance penicillin production, as their genetic uniformity ensures consistent results in fermentation processes.

From an ecological perspective, the haploid state of fungal spores enhances their adaptability and survival. Haploid spores can quickly colonize new environments, as they are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Once they land in a suitable habitat, they can germinate and, through mitosis, develop into a multicellular haploid structure called a gametophyte. If conditions allow, gametangia (reproductive organs) form, and fertilization occurs, restoring the diploid phase. This alternation of generations—between haploid and diploid phases—is a hallmark of fungal life cycles, ensuring both genetic diversity and stability.

Practical tips for working with fungal spores include maintaining sterile conditions to prevent contamination, as spores are highly susceptible to competing microorganisms. For laboratory cultivation, spores are often inoculated onto agar plates or liquid media containing nutrients like glucose and nitrogen sources. Temperature and humidity control are critical, as most fungi thrive in environments ranging from 20°C to 30°C with relative humidity above 80%. For example, mushroom cultivators often use pasteurized substrate and regulate environmental conditions to optimize spore germination and mycelial growth.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of most fungal spores, produced via meiosis, is a fundamental aspect of their biology, influencing their genetic diversity, ecological success, and practical utility. Whether in scientific research, biotechnology, or agriculture, understanding this characteristic allows for better manipulation and application of fungi. By appreciating the role of meiosis in spore production and the advantages of haploidy, we can harness the potential of fungi more effectively, from producing life-saving drugs to decomposing organic matter in ecosystems.

Mastering Spore Cheats: A Step-by-Step Guide to Enhance Your Gameplay

You may want to see also

Spores in Plants: Plant spores (e.g., ferns) are typically haploid, part of alternation of generations

Plant spores, particularly those of ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants, are predominantly haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. This characteristic is a cornerstone of the alternation of generations, a life cycle unique to plants and some algae. In this cycle, the haploid spore germinates into a gametophyte, a structure that produces gametes (sperm and eggs). When these gametes unite, they form a diploid zygote, which develops into the sporophyte generation. The sporophyte then produces spores through meiosis, restarting the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as the haploid phase allows for rapid mutation and evolution, while the diploid phase provides stability.

Consider the fern as a prime example. When a fern releases spores, each spore is haploid and develops into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus) on the forest floor. This gametophyte is bisexual, producing both sperm and eggs. After fertilization, the resulting zygote grows into the familiar fern plant, which is diploid. The fern plant then produces spores via structures called sporangia, located on the undersides of its leaves. This cycle highlights the critical role of haploid spores in bridging the two generations, ensuring the plant’s survival across diverse environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of spores is essential for horticulture and conservation. For instance, gardeners propagating ferns from spores must provide a moist, shaded environment to mimic the conditions where gametophytes thrive. Spores are incredibly lightweight and can travel long distances, making them ideal for colonizing new habitats. However, their haploid state also makes them susceptible to environmental stresses, such as desiccation or extreme temperatures. Conservation efforts for endangered plant species often involve spore banking, where spores are stored in controlled conditions to preserve genetic diversity.

Comparatively, the haploid nature of plant spores contrasts with the diploid spores found in some fungi, such as basidiomycetes (e.g., mushrooms). While fungal spores are often diploid, plant spores are strictly haploid in the alternation of generations. This distinction underscores the evolutionary divergence between plants and fungi, despite their shared reliance on spores for reproduction. For educators and students, this comparison provides a rich opportunity to explore the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of plant spores is not merely a biological detail but a fundamental aspect of plant life cycles. It drives genetic diversity, enables adaptation, and ensures the continuity of species. Whether in the classroom, the garden, or the wild, recognizing the role of haploid spores in the alternation of generations offers valuable insights into the intricate mechanisms of plant survival and evolution. By studying these tiny, single-celled structures, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and resilience of the plant kingdom.

Proper Storage Tips for Spore Syringes: Maximize Longevity and Viability

You may want to see also

Spores in Bacteria: Bacterial spores are diploid, formed for survival, not reproduction

Bacterial spores defy the typical haploid-diploid dichotomy seen in eukaryotic organisms. Unlike fungal or plant spores, which are predominantly haploid, bacterial spores are diploid, retaining a complete set of genetic material. This distinction is crucial because it highlights the unique role of bacterial spores: they are not reproductive structures but rather survival mechanisms. Formed under conditions of nutrient depletion or environmental stress, these spores encapsulate the bacterium’s DNA within a protective coat, ensuring long-term endurance rather than immediate propagation.

Consider the process of sporulation in *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied bacterium. When starved, it asymmetrically divides into a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. The forespore eventually becomes the spore, while the mother cell degrades, providing nutrients for spore maturation. This process results in a diploid spore, as the genetic material is not halved. The spore’s diploid nature is not for genetic diversity but for stability, allowing it to withstand extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation for years or even centuries.

From a practical standpoint, understanding bacterial spores’ diploid nature is essential in fields like food safety and medicine. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores, which are diploid, can survive pasteurization temperatures and germinate under favorable conditions, leading to botulism. To neutralize such threats, industries employ autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, ensuring spore inactivation. Similarly, in healthcare, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* require stringent disinfection protocols, as their diploid spores resist many common sanitizers.

Comparatively, fungal spores, such as those of yeast, are typically haploid and serve reproductive purposes, dispersing to colonize new environments. Bacterial spores, however, are not dispersal agents but dormant forms awaiting optimal conditions to reactivate. This fundamental difference underscores the importance of tailoring strategies to combat bacterial spores, whether in sterilizing medical equipment or preserving food. For example, while haploid fungal spores may succumb to surface disinfectants, diploid bacterial spores demand more aggressive methods, such as spore-specific biocides or high-pressure steam treatment.

In conclusion, bacterial spores’ diploid nature is a testament to their role as survival structures rather than reproductive agents. This distinction has profound implications for industries ranging from healthcare to food production, necessitating targeted approaches to eliminate these resilient forms. By recognizing the unique biology of bacterial spores, we can develop more effective strategies to manage and mitigate their persistence in critical environments.

Are Spores Autotrophic or Heterotrophic? Unraveling Their Nutritional Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes.

Spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells.

In some organisms, such as certain fungi, spores can be diploid if they are formed through mitosis or other processes that do not involve meiosis.

Haploid spores germinate and grow into haploid individuals or structures, which then undergo fertilization to restore the diploid state in the life cycle.

Diploid stages typically involve growth and development, while haploid stages, represented by spores, are often involved in dispersal and survival in adverse conditions.