The question of whether spores are the same as sperm often arises due to their similar-sounding names, but they are fundamentally different biological structures with distinct functions. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, primarily serving as a means of asexual reproduction and survival in harsh conditions. They are typically single-celled and can develop into a new organism under favorable conditions. In contrast, sperm is a male reproductive cell in animals and humans, designed to fertilize a female egg during sexual reproduction. While both spores and sperm play roles in reproduction, their mechanisms, structures, and purposes are entirely unrelated, reflecting the diverse strategies of different life forms to ensure their continuity.

What You'll Learn

Definition of Spores vs. Sperm

Spores and sperm are fundamentally different biological entities, each serving distinct reproductive purposes in their respective organisms. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions. They are typically unicellular and highly resistant to harsh environments, allowing them to survive dormancy for extended periods. In contrast, sperm are male reproductive cells in animals and humans, designed to fertilize a female egg. They are motile, equipped with a tail (flagellum) to swim toward the egg, and contain half the genetic material needed to form a new organism. This distinction highlights their roles: spores are for asexual or sexual reproduction in non-animal species, while sperm are exclusively for sexual reproduction in animals.

To understand their differences, consider their structures and functions. Spores are often encased in protective layers, such as a thick cell wall, enabling them to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. For example, fungal spores can remain viable in soil for decades, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. Sperm, however, are fragile and short-lived outside the body, requiring a fluid medium to maintain motility. In humans, sperm must traverse the female reproductive tract, a journey that only a few survive, to reach and fertilize the egg. This comparison underscores the adaptability of spores versus the specialized, transient nature of sperm.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial in fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. Farmers use fungal spores as bio-pesticides to control pests without harmful chemicals, leveraging their resilience and ability to colonize target organisms. In contrast, fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) rely on the viability and motility of sperm, often requiring laboratory techniques to select the most robust candidates. For instance, sperm washing and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) are procedures that enhance fertilization success by isolating healthy sperm and directly injecting them into eggs. These applications demonstrate how the unique properties of spores and sperm are harnessed for specific purposes.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both spores and sperm are reproductive units, their mechanisms and contexts differ dramatically. Spores are versatile, enabling organisms to disperse and survive in diverse environments, whereas sperm are highly specialized for a single, critical function: fertilization. This specialization reflects the evolutionary strategies of their respective organisms. Plants and fungi use spores to colonize new habitats and persist through adverse conditions, while animals rely on the rapid, directed movement of sperm to ensure successful reproduction. Recognizing these distinctions clarifies their roles in biology and their practical applications in various industries.

In summary, spores and sperm are not interchangeable; they are tailored to the reproductive needs of their organisms. Spores excel in durability and dispersal, making them essential for the survival and propagation of non-animal species. Sperm, with their motility and genetic contribution, are pivotal in animal reproduction. By appreciating these differences, we can better utilize their unique properties in agriculture, medicine, and conservation, advancing both scientific understanding and practical solutions.

Update Spore Without Login: Easy Steps for Seamless Gameplay

You may want to see also

Reproductive Roles in Organisms

Spores and sperm are both reproductive units, yet they serve distinct roles across different organisms. Spores, typically found in plants, fungi, and some protists, are resilient, single-celled structures designed for survival and dispersal. They can withstand harsh conditions—extreme temperatures, drought, or lack of nutrients—and remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination. Sperm, in contrast, are specialized reproductive cells in animals and certain plants, optimized for mobility and fertilization. Their primary function is to deliver genetic material to an egg, requiring a supportive environment to remain viable for only a short period. This fundamental difference highlights how reproductive strategies adapt to the organism’s environment and life cycle.

Consider the reproductive efficiency of spores in ferns versus the role of sperm in humans. Ferns release thousands of spores into the wind, ensuring at least a few land in suitable habitats to grow into new plants. This scattergun approach maximizes survival in unpredictable environments. Human sperm, however, are produced in vast quantities (up to 100 million per ejaculate) but rely on a precise, protected journey through the reproductive tract to reach the egg. While ferns invest in quantity and durability, humans prioritize quality and mobility, reflecting their respective ecological niches. This comparison underscores how reproductive roles are finely tuned to the organism’s survival needs.

For practical insights, gardeners can leverage spore reproduction to propagate plants like ferns or mosses. Collect spores from mature plants (e.g., by placing a paper under fern leaves) and sprinkle them on moist, well-drained soil in a shaded area. Maintain consistent moisture, and within weeks, tiny gametophytes will emerge, eventually growing into new plants. In contrast, understanding sperm viability is crucial for human fertility. Sperm can survive in the female reproductive tract for up to 5 days, but their motility and DNA integrity decline over time. Couples trying to conceive should time intercourse within this window for optimal results. These examples illustrate how knowledge of reproductive roles can be applied in both natural and clinical settings.

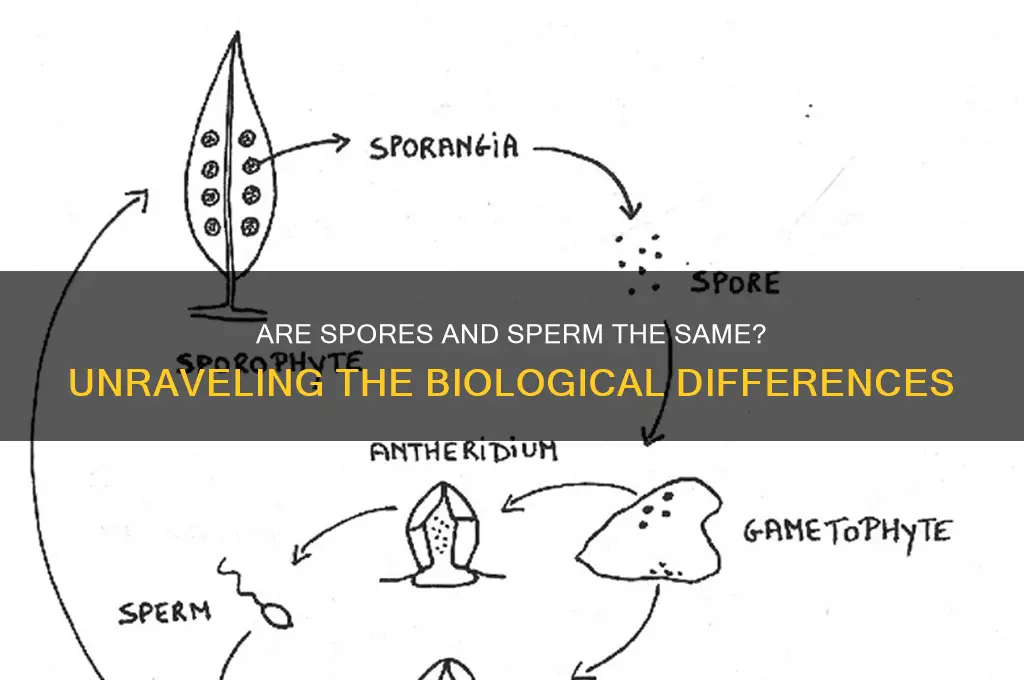

A cautionary note: confusing spores and sperm can lead to misconceptions about reproduction. For instance, while both are microscopic, spores are not involved in sexual reproduction in the same way as sperm. Spores undergo alternation of generations, switching between haploid and diploid phases, whereas sperm are part of a direct fertilization process. Educators and communicators should emphasize these distinctions to avoid oversimplifying complex biological mechanisms. Clarity in this area fosters a deeper appreciation for the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world.

In conclusion, the reproductive roles of spores and sperm exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species survival. Spores thrive through resilience and dispersal, while sperm excel in mobility and precision. By studying these differences, we gain practical tools—from plant propagation to fertility optimization—and a richer understanding of life’s adaptability. Recognizing these unique roles not only clarifies biological concepts but also inspires innovation across fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation.

Fixing Spore on Steam: Troubleshooting Tips for Seamless Gameplay

You may want to see also

Structural Differences Between Spores and Sperm

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, differ fundamentally in structure, function, and purpose. Spores are resilient, single-celled structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, designed to survive harsh conditions and disperse widely. Sperm, in contrast, are motile male reproductive cells in animals, optimized for fertilization. Their structural differences reflect these distinct roles, from protective outer layers to internal cellular machinery.

Consider the cell wall composition as a starting point. Spores possess a thick, durable cell wall often made of sporopollenin, a highly resistant polymer that shields the genetic material from desiccation, radiation, and extreme temperatures. This wall is essential for long-term survival in adverse environments, such as the soil or air. Sperm, however, lack a cell wall entirely. Instead, they have a flexible plasma membrane that allows for movement and interaction with the female reproductive tract. This membrane is rich in proteins and lipids, facilitating recognition and fusion with the egg during fertilization.

Another critical structural difference lies in motility mechanisms. Sperm are equipped with a flagellum, a whip-like tail that propels them through fluid environments. This tail is powered by microtubules arranged in a 9+2 pattern, a structure unique to motile cells. Spores, on the other hand, are non-motile. They rely on external forces like wind, water, or animals for dispersal. Their energy is conserved for germination rather than movement, a strategy that prioritizes survival over active travel.

The internal organization of these cells further highlights their divergence. Spores contain stored nutrients, such as lipids and starches, to sustain the developing organism during germination. They also have a dormant nucleus, ready to activate under favorable conditions. Sperm, conversely, are minimalistic in design. Their primary function is to deliver genetic material, so they carry little cytoplasm and no stored nutrients. The nucleus is compact, and the cell is streamlined to maximize speed and efficiency.

Practically speaking, understanding these structural differences has implications for fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, spore resistance to environmental stressors informs strategies for seed preservation and fungal control. Sperm structure, meanwhile, is crucial in assisted reproductive technologies, where motility and viability are key parameters. By recognizing these distinctions, researchers and practitioners can tailor approaches to optimize outcomes in both plant and animal reproduction.

Mastering the Art of Spores: A Step-by-Step Guide to Creation

You may want to see also

Organisms That Produce Spores vs. Sperm

Spores and sperm are both reproductive structures, yet they serve distinct purposes and are produced by entirely different organisms. Spores are typically associated with plants, fungi, and some bacteria, acting as resilient, dormant cells capable of surviving harsh conditions. In contrast, sperm are exclusively produced by animals and certain protists, functioning as male gametes that fertilize female eggs. This fundamental difference in origin and function underscores the unique evolutionary strategies of spore-producing and sperm-producing organisms.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a spore-producing plant. Ferns release spores into the environment, which can remain viable for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. Once activated, a spore grows into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte that produces both sperm and eggs. This contrasts sharply with the reproductive process of animals, where sperm are actively motile cells, often short-lived, and require immediate access to an egg for fertilization. For instance, human sperm can survive in the female reproductive tract for up to 5 days, but their primary function is to swim toward the egg, a task accomplished within minutes to hours after ejaculation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial in fields like agriculture and medicine. Farmers cultivating spore-producing crops, such as mushrooms, must control humidity and temperature to encourage spore germination. Conversely, in assisted reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization (IVF), sperm are carefully selected and prepared to ensure optimal motility and viability. For example, sperm used in IVF are often washed and concentrated to a dosage of 100,000–200,000 sperm per milliliter, significantly higher than the average ejaculate concentration of 15 million sperm per milliliter.

A comparative analysis reveals the trade-offs between these reproductive strategies. Spores offer longevity and resistance to environmental stress, making them ideal for organisms in unpredictable habitats. Sperm, however, prioritize speed and efficiency, reflecting the competitive nature of animal reproduction. This distinction is further highlighted by the energy investment: spore production is generally less resource-intensive than sperm production, which requires substantial metabolic energy, particularly in species with high sperm counts. For example, a single male fruit fly produces approximately 1,000 sperm per day, while a human male produces millions in the same timeframe.

In conclusion, while both spores and sperm are reproductive units, their roles, mechanisms, and ecological implications diverge sharply. Recognizing these differences not only enriches our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications in agriculture, conservation, and medicine. Whether you're cultivating spore-producing fungi or studying sperm viability for fertility treatments, the unique characteristics of these structures demand tailored approaches for success.

Preventing Contamination: Do Spores Compromise Mushroom Grow Room Success?

You may want to see also

Environmental Survival Capabilities Compared

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, exhibit starkly different environmental survival capabilities shaped by their biological purposes and structures. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and certain bacteria, are designed for endurance. They possess thick, protective walls that shield their genetic material from desiccation, extreme temperatures, and radiation. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive boiling water for hours and remain viable in soil for centuries. This resilience allows spores to persist in harsh conditions, waiting for optimal growth environments. Sperm, in contrast, are fragile and short-lived. They lack protective outer layers and rely on aqueous environments to maintain motility. Human sperm, for example, can survive in the female reproductive tract for only 3–5 days, and their viability drops rapidly outside this environment. This vulnerability underscores sperm’s specialized role in immediate fertilization rather than long-term survival.

To compare their survival strategies, consider their responses to environmental stressors. Spores thrive in adversity, employing mechanisms like DNA repair enzymes and metabolic dormancy to withstand UV radiation, freezing temperatures, and chemical exposure. For example, fungal spores can survive doses of ionizing radiation up to 10,000 Gray, far exceeding the lethal limit for most organisms. Sperm, however, are highly sensitive to such conditions. Exposure to temperatures above 40°C (104°F) or pH levels outside 7.2–7.8 can render sperm immotile within minutes. Even slight dehydration or oxidative stress can damage their plasma membrane and DNA, compromising fertility. These differences highlight how spores prioritize longevity and dispersal, while sperm prioritize rapid movement and immediate function.

Practical applications of these survival capabilities differ significantly. Spores’ durability makes them ideal for agricultural and industrial uses. For instance, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used in bioinsecticides, surviving on crops for weeks to control pests. In contrast, sperm’s fragility necessitates controlled environments for assisted reproduction technologies. Cryopreservation of sperm involves precise cooling rates (e.g., 1–2°C per minute) and protective media like glycerol to prevent ice crystal formation, ensuring viability for decades. However, this process is resource-intensive and requires specialized equipment, unlike spores, which can be stored at room temperature with minimal preparation.

A key takeaway is that spores and sperm represent divergent evolutionary strategies for survival and reproduction. Spores’ robustness enables them to act as environmental reservoirs, ensuring species continuity across generations. Sperm, by contrast, are optimized for short-term success in specific conditions, reflecting their role in sexual reproduction. Understanding these differences has practical implications, from developing spore-based solutions for environmental challenges to improving sperm preservation techniques in reproductive medicine. By studying their survival mechanisms, we gain insights into the adaptability of life and the trade-offs between endurance and immediacy.

Unlocking the Secrets: How to Successfully Collect Fern Spores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores and sperm are entirely different biological structures. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, while sperm is a male reproductive cell in animals and humans.

Spores serve as a means of asexual reproduction and survival in harsh conditions for organisms like fungi, plants (e.g., ferns), and certain bacteria. They can remain dormant until favorable conditions return.

Sperm is a male gamete (reproductive cell) in animals and humans, whose primary purpose is to fertilize a female egg (ovum) to create a new organism through sexual reproduction.

No, plants and fungi do not produce sperm. Instead, they often reproduce via spores or other methods like pollination (in plants) or fungal hyphae. Sperm is specific to animals and humans.