Streptococcus salivarius is a gram-positive, non-spore-forming bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. As a member of the normal flora, it plays a role in maintaining oral health and preventing colonization by pathogenic microorganisms. The question of whether *S. salivarius* is spore-forming is straightforward: it does not produce spores. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can survive harsh conditions by forming dormant, highly resistant structures, *S. salivarius* relies on its ability to thrive in its natural habitat without this survival mechanism. This characteristic is consistent with its classification within the Streptococcus genus, which generally lacks spore-forming capabilities. Understanding its non-spore-forming nature is essential for studying its role in human health and its interactions with other microorganisms.

What You'll Learn

- Streptococcus salivarius classification: Non-spore forming, Gram-positive coccus, part of normal human oral flora

- Spore formation process: Requires specific bacteria; S. salivarius lacks spore-forming capabilities

- Survival mechanisms: Relies on biofilm formation, not spore formation, for environmental persistence

- Clinical relevance: Non-spore forming nature impacts treatment and antibiotic susceptibility patterns

- Comparative analysis: Unlike Bacillus or Clostridium, S. salivarius does not produce spores

Streptococcus salivarius classification: Non-spore forming, Gram-positive coccus, part of normal human oral flora

Streptococcus salivarius, a bacterium commonly found in the human oral cavity, is definitively classified as non-spore forming. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Clostridium or Bacillus, which produce highly resistant endospores to survive harsh conditions, S. salivarius lacks this survival mechanism. This characteristic is crucial for understanding its behavior in the oral environment, where it thrives in the presence of moisture, nutrients, and stable conditions provided by the human mouth. The absence of spore formation limits its ability to persist outside the host for extended periods, making it highly dependent on the oral ecosystem for survival.

From a taxonomic perspective, S. salivarius is a Gram-positive coccus, meaning it retains the crystal violet stain in Gram staining due to its thick peptidoglycan cell wall. This classification places it within the Firmicutes phylum, a group of bacteria known for their low GC content and diverse metabolic capabilities. Its coccoid shape, appearing in pairs or chains, is a defining morphological feature that distinguishes it from other oral bacteria. For clinicians and microbiologists, recognizing these traits is essential for accurate identification and differentiation from pathogenic species, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, which share similar habitats but exhibit distinct virulence factors.

As part of the normal human oral flora, S. salivarius plays a symbiotic role in maintaining oral health. It competes with pathogenic bacteria for resources and adhesion sites on mucosal surfaces, effectively reducing the risk of infections like dental caries and pharyngitis. Probiotic formulations containing S. salivarius K12, for instance, are commercially available to support oral and upper respiratory health, particularly in children and adults prone to recurrent streptococcal infections. Dosage typically ranges from 1 to 5 billion CFUs daily, depending on age and health status, with adherence to product guidelines ensuring optimal efficacy.

Comparatively, the non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius contrasts with spore-forming pathogens, which pose challenges in disinfection and treatment due to their resilience. This distinction highlights the importance of targeted antimicrobial strategies in oral care. For example, chlorhexidine mouthwashes effectively reduce S. salivarius populations but are less effective against spore-forming bacteria, underscoring the need for tailored interventions based on bacterial classification. Understanding these differences empowers healthcare providers to recommend appropriate therapies, such as probiotics for flora balance or antibiotics for specific infections, without disrupting the oral microbiome unnecessarily.

Practically, maintaining a healthy oral environment supports the beneficial role of S. salivarius while minimizing overgrowth. Simple measures like twice-daily brushing, flossing, and regular dental check-ups can prevent dysbiosis, where harmful bacteria outcompete beneficial species. For individuals using S. salivarius probiotics, consistency is key; taking the supplement at the same time daily, preferably after meals, enhances colonization and efficacy. Avoiding antimicrobial mouthwashes during probiotic therapy ensures the survival of introduced strains, maximizing their protective effects. By integrating these practices, individuals can harness the natural defenses provided by S. salivarius while mitigating risks associated with its non-spore-forming limitations.

Are White Flecks a Sign of Black Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore formation process: Requires specific bacteria; S. salivarius lacks spore-forming capabilities

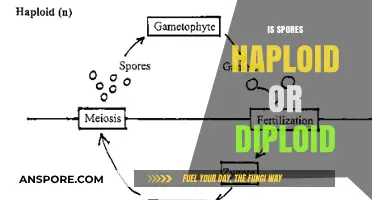

Spore formation is a survival mechanism exclusive to certain bacterial species, notably those in the *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* genera. This process involves the creation of a highly resistant, dormant structure that can withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. For bacteria, sporulation is a complex, energy-intensive process triggered by nutrient deprivation and other environmental stressors. *Streptococcus salivarius*, a common inhabitant of the human oral cavity, does not possess the genetic or physiological machinery required for spore formation. Its survival strategies instead rely on biofilm formation and metabolic adaptability within its niche.

To understand why *S. salivarius* lacks spore-forming capabilities, consider the evolutionary pressures shaping bacterial survival mechanisms. Spore formation is advantageous for bacteria in unpredictable environments, such as soil, where resources fluctuate dramatically. In contrast, *S. salivarius* thrives in the relatively stable environment of the human mouth, where temperature, moisture, and nutrient availability are consistent. Its survival depends on rapid replication and adherence to mucosal surfaces rather than long-term dormancy. Sporulation genes, absent in *S. salivarius*, are instead conserved in bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis*, which requires this mechanism to endure harsh conditions outside a host.

From a practical standpoint, the inability of *S. salivarius* to form spores simplifies its management in clinical and industrial settings. Unlike spore-forming pathogens, which require extreme measures (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes) for eradication, *S. salivarius* is susceptible to standard disinfection methods. For instance, ethanol-based mouthwashes (70% concentration) effectively reduce its population, as do routine dental hygiene practices. This distinction is critical in healthcare, where spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* pose significant challenges due to their resistance to common sanitizers.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in *S. salivarius* highlights the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. While sporulation is a high-energy investment for long-term survival, *S. salivarius* prioritizes rapid colonization and resource utilization. This trade-off is evident in its role as a probiotic in oral health supplements, where its viability depends on protective formulations (e.g., microencapsulation) rather than inherent spore resistance. For consumers, understanding this difference ensures realistic expectations: *S. salivarius* supplements must be stored under controlled conditions (e.g., refrigeration at 2–8°C) to maintain potency, unlike spore-based products, which remain stable at room temperature.

In summary, the spore formation process is a specialized adaptation limited to specific bacterial groups, with *S. salivarius* conspicuously absent from this category. This distinction has practical implications for its control, application, and storage. While spore-forming bacteria demand rigorous eradication methods, *S. salivarius* can be managed with standard practices, making it both a benign commensal and a manageable target in clinical contexts. Recognizing these differences empowers informed decision-making in healthcare, industry, and personal wellness.

Truffle Spores Pricing: Understanding the Cost of Cultivation

You may want to see also

Survival mechanisms: Relies on biofilm formation, not spore formation, for environmental persistence

Streptococcus salivarius, a common inhabitant of the human oral cavity, does not form spores as a survival mechanism. Instead, it relies on biofilm formation to persist in its environment. This distinction is crucial for understanding its behavior and developing strategies to manage its presence. Biofilms are complex communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced protective matrix, allowing them to adhere to surfaces and resist external stressors like antibiotics and host immune responses.

Analyzing the survival mechanisms of *S. salivarius* reveals the strategic advantage of biofilm formation. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which enter a dormant state to endure harsh conditions, *S. salivarius* thrives by clustering together. This communal structure enhances nutrient sharing, facilitates genetic exchange, and provides a physical barrier against antimicrobial agents. For instance, in dental plaque, *S. salivarius* biofilms contribute to the early stages of formation, creating a foundation for other species to colonize. However, this mechanism also poses challenges, as biofilms are notoriously difficult to eradicate, often requiring mechanical disruption or high-dose antimicrobial therapy.

To counteract *S. salivarius* biofilms, practical interventions focus on prevention and targeted treatment. Regular oral hygiene practices, such as brushing twice daily with fluoride toothpaste and flossing, disrupt biofilm formation. For clinical settings, chlorhexidine mouthwash at a concentration of 0.12%–0.2% can reduce biofilm adherence, but prolonged use may lead to staining or altered taste sensation. In cases of persistent infections, combination therapies involving enzymes like DNase, which degrade the biofilm matrix, or antimicrobial peptides, which penetrate the biofilm, show promise.

Comparing *S. salivarius* to spore-forming bacteria highlights the trade-offs in survival strategies. While spores offer long-term resilience in extreme environments, biofilms provide immediate protection and facilitate community-based survival in stable habitats like the oral cavity. This difference underscores the importance of tailoring control measures to the specific mechanism employed by the bacterium. For example, while heat or radiation effectively eliminate spores, biofilms require mechanical or biochemical disruption to be neutralized.

In conclusion, understanding that *S. salivarius* relies on biofilm formation, not spore formation, for environmental persistence is key to managing its impact. By targeting biofilm structures through preventive measures and specialized treatments, individuals and healthcare providers can mitigate its role in oral and systemic infections. This knowledge not only informs clinical practice but also emphasizes the importance of adapting strategies to the unique survival mechanisms of different microorganisms.

Mastering Terraforming in Spore: A Step-by-Step Planet Creation Guide

You may want to see also

Clinical relevance: Non-spore forming nature impacts treatment and antibiotic susceptibility patterns

Streptococcus salivarius, a common inhabitant of the human oral cavity, is not spore-forming. This characteristic fundamentally distinguishes it from spore-forming pathogens like Clostridioides difficile, which can survive harsh conditions and recur after treatment. The non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius has direct implications for its clinical management, particularly in the context of antibiotic therapy and infection control. Unlike spore-formers, S. salivarius relies on active replication and metabolic processes for survival, making it more susceptible to standard antimicrobial agents under typical treatment durations.

From a treatment perspective, the non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius simplifies therapeutic approaches. For instance, in cases of S. salivarius-related infections, such as dental caries or pharyngitis, standard antibiotic regimens (e.g., penicillin 250–500 mg every 6 hours for adults) are often sufficient. There is no need for prolonged or high-dose therapies typically required for spore-forming bacteria, which may necessitate extended treatment durations (e.g., 10–14 days for C. difficile) or combination therapies. This reduces the risk of antibiotic overuse and associated complications like Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), a common adverse effect of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

However, the non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius also influences its susceptibility patterns. While it is generally sensitive to beta-lactams, macrolides, and tetracyclines, emerging resistance is a concern, particularly in healthcare settings. For example, penicillin-resistant strains are rare but have been reported, necessitating susceptibility testing in recurrent or severe infections. In contrast, spore-forming bacteria often exhibit intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics due to their dormant spore state, complicating treatment. For S. salivarius, resistance is primarily acquired through genetic mutations or horizontal gene transfer, making surveillance and judicious antibiotic use critical.

Practically, clinicians should consider the non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius when selecting empiric therapy. For pediatric patients, amoxicillin (50 mg/kg/day divided every 8 hours) remains a first-line option for suspected S. salivarius infections, given its efficacy and narrow spectrum. In immunocompromised patients or those with recurrent infections, culture and sensitivity testing should guide treatment to avoid inappropriate broad-spectrum antibiotic use. Additionally, infection control measures, such as hand hygiene and surface disinfection, are effective in preventing S. salivarius transmission, as spores are not a concern.

In summary, the non-spore-forming nature of S. salivarius streamlines treatment by eliminating the need for spore-targeted therapies but requires vigilance against emerging resistance. Clinicians should leverage this characteristic to optimize antibiotic selection, minimize overuse, and tailor therapy based on susceptibility patterns. By understanding this unique trait, healthcare providers can effectively manage S. salivarius infections while preserving the efficacy of antimicrobial agents.

Mastering Darkspore: Unleashing Your Abilities for Ultimate Dominance

You may want to see also

Comparative analysis: Unlike Bacillus or Clostridium, S. salivarius does not produce spores

Streptococcus salivarius, a common inhabitant of the human oral cavity, stands apart from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium in a critical survival mechanism. While Bacillus and Clostridium species produce highly resistant spores to endure harsh conditions, S. salivarius lacks this ability. This distinction significantly influences their ecological niches and interactions with their environments.

Spores, essentially dormant and resilient cells, allow Bacillus and Clostridium to survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to disinfectants. This adaptability enables them to persist in diverse environments, from soil to the human gut, posing challenges in food preservation and medical settings. In contrast, S. salivarius, being non-spore-forming, relies on its ability to thrive in the stable, nutrient-rich environment of the mouth, where it plays a role in maintaining oral health by competing with pathogenic bacteria.

Understanding this difference is crucial in clinical and industrial applications. For instance, spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium difficile are notorious for causing antibiotic-associated diarrhea, requiring specific treatment strategies due to their spore-mediated persistence. S. salivarius, on the other hand, is often harnessed in probiotics, such as those containing 2-6 billion CFUs (colony-forming units) per dose, to support oral and upper respiratory health. Its non-spore-forming nature means it does not survive long outside its host, necessitating careful formulation and storage of probiotic products to ensure viability.

From a practical standpoint, this comparative analysis highlights the importance of tailoring antimicrobial strategies. While spore-formers may require high-temperature sterilization (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes) or specific sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide, non-spore-forming bacteria like S. salivarius are more susceptible to standard disinfectants and antibiotics. For individuals using S. salivarius probiotics, storing products at 2-8°C and avoiding exposure to moisture ensures potency. This knowledge also underscores the need for targeted research into non-spore-forming bacteria, as their survival strategies differ markedly from their spore-forming counterparts.

In summary, the absence of spore formation in S. salivarius contrasts sharply with the resilience of Bacillus and Clostridium, shaping their roles in health, disease, and industry. Recognizing this distinction not only aids in effective management of bacterial populations but also informs the development of tailored interventions, from probiotic formulations to disinfection protocols. Whether in a clinical, industrial, or personal health context, this comparative analysis provides actionable insights into the unique biology of S. salivarius.

Understanding Black Mold: How and When Spores Are Released into Air

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Streptococcus salivarius is not a spore-forming bacterium. It is a Gram-positive, non-spore-forming coccus.

Being non-spore-forming means Streptococcus salivarius does not produce endospores, which are highly resistant structures used by some bacteria to survive harsh conditions.

No, Streptococcus salivarius lacks the ability to form spores, so it is less resistant to extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, or radiation compared to spore-forming bacteria.

No, none of the Streptococcus species, including Streptococcus salivarius, are known to be spore-forming. They are all non-spore-forming bacteria.