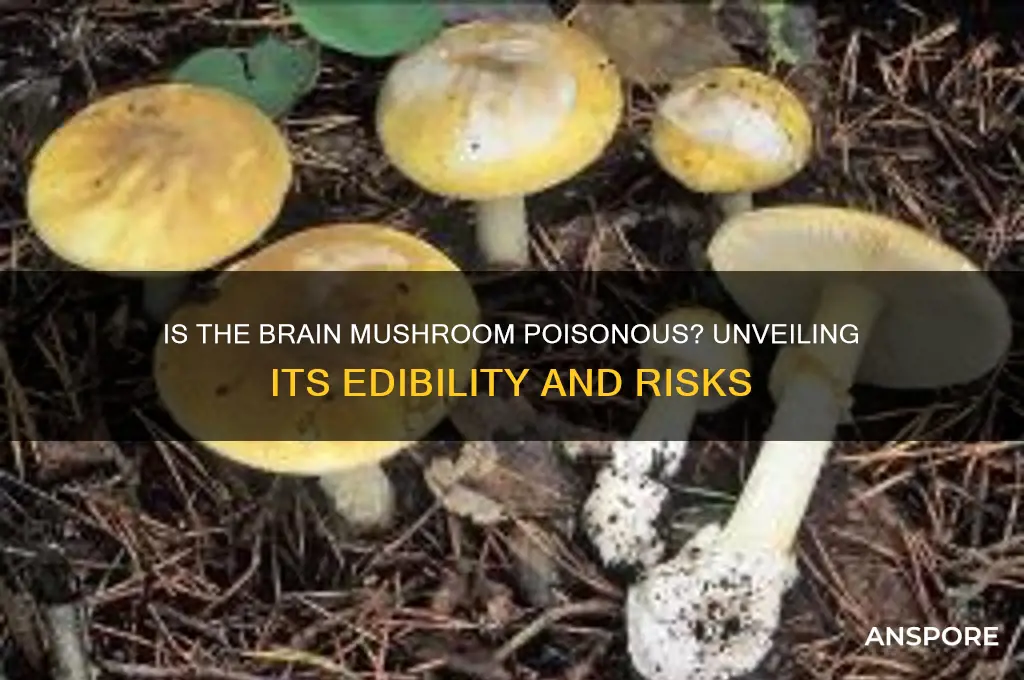

The question of whether the brain mushroom, also known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, is poisonous has long intrigued both foragers and mycologists. While this fungus is prized in some cultures for its meaty texture and unique flavor, it contains a toxin called gyromitrin, which can break down into toxic compounds, including monomethylhydrazine. Consumption of the brain mushroom without proper preparation, such as thorough cooking and drying, can lead to severe symptoms like gastrointestinal distress, neurological issues, and in extreme cases, organ failure or death. Despite its risks, many enthusiasts argue that careful handling renders it safe, sparking ongoing debates about its safety and culinary value.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Brain Mushroom |

| Scientific Name | Mycena species (e.g., Mycena haematopus, Mycena purpureofusca) |

| Toxicity | Generally considered non-toxic but some species may cause mild gastrointestinal upset if ingested |

| Edibility | Not recommended for consumption due to lack of culinary value and potential confusion with toxic species |

| Appearance | Small, delicate mushrooms with a brain-like or wrinkled cap; often reddish, purplish, or brown hues |

| Habitat | Found in wooded areas, often on decaying wood or leaf litter |

| Spores | White to pale pink, depending on the species |

| Look-alikes | Can resemble toxic species like Galerina marginata or Cortinarius spp., which are poisonous |

| Precautions | Avoid consumption unless positively identified by an expert; some species may cause allergic reactions |

| Medicinal Use | No significant medicinal properties reported |

| Conservation | Not considered endangered, but habitat preservation is important for fungal ecosystems |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Symptoms of Brain Mushroom Poisoning

The brain mushroom, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, is notorious for its deceptive appearance and toxic properties. While it resembles edible morels, consuming it can lead to severe poisoning. Understanding the symptoms of brain mushroom poisoning is crucial for anyone foraging wild mushrooms, as early recognition can be life-saving.

Symptoms typically appear within 6 to 12 hours after ingestion, though they can manifest as early as 2 hours or as late as 24 hours. Initial signs often mimic food poisoning, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms may lead individuals to dismiss the severity of their condition, but they are the body’s first warning of a toxic reaction. Unlike common foodborne illnesses, brain mushroom poisoning progresses rapidly, escalating to more serious complications if left untreated.

As the toxins, primarily gyromitrin, break down into monomethylhydrazine, the poisoning can affect multiple organ systems. Central nervous system symptoms emerge, such as dizziness, confusion, and seizures. In severe cases, victims may experience coma or respiratory failure. Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass and weaker immune systems, but even healthy adults can suffer life-threatening consequences from a single meal containing brain mushrooms.

Treatment for brain mushroom poisoning is time-sensitive and requires immediate medical attention. Gastric lavage (stomach pumping) and activated charcoal may be administered to reduce toxin absorption. Intravenous fluids and medications to control seizures or stabilize vital signs are often necessary. In extreme cases, dialysis or respiratory support may be required. Foragers should always carry a mushroom identification guide and avoid consuming any mushroom unless absolutely certain of its edibility.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Brain mushrooms are often misidentified due to their brain-like appearance and false morel resemblance. Key distinguishing features include their wrinkled, lobed caps and brittle, hollow stems. If in doubt, consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether. Remember, no meal is worth risking your health—when it comes to wild mushrooms, caution is paramount.

Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms in Australian Yards: A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Identifying Toxic Brain Mushroom Species

The brain-like appearance of certain mushrooms can be both fascinating and deceptive, especially when some species are toxic. Identifying these toxic varieties requires a keen eye and knowledge of specific characteristics. For instance, the Gyromitra esculenta, commonly known as the false morel, resembles a brain but contains gyromitrin, a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in extreme cases, organ failure. Recognizing its wrinkled, brain-like cap and bulky stem is crucial, as it is often mistaken for edible morels. Always cross-check with reliable field guides or consult an expert before consumption.

Analyzing spore color is another critical step in identifying toxic brain mushrooms. While not all toxic species have distinctive spore colors, some, like the Conocybe filaris, produce rusty-brown spores that can be observed using a spore print. This species, often found in lawns and gardens, contains amatoxins, which can cause liver and kidney damage within hours of ingestion. Amatoxins are particularly dangerous because symptoms may not appear until 6–24 hours after consumption, making early identification essential. A simple spore print test involves placing the mushroom cap on paper overnight, providing valuable clues about its toxicity.

Instructing foragers to focus on habitat and seasonality can further aid in identification. Toxic brain mushrooms often thrive in specific environments. For example, Clathrus archeri, or the octopus stinkhorn, is a brain-like fungus found in wood chips or mulch, emitting a foul odor to attract flies for spore dispersal. While not deadly, it can cause gastrointestinal upset if ingested. Similarly, Exidia nigricans, a black, brain-like jelly fungus, is harmless but often confused with toxic species in damp, decaying wood. Always note the mushroom’s location and time of year, as these details can narrow down potential toxic candidates.

Persuasively, it’s worth emphasizing that relying solely on visual identification can be risky. Some toxic brain mushrooms, like Cortinarius species, may appear innocuous but contain orellanine, a toxin causing delayed kidney failure. Carrying a portable mushroom testing kit, which detects toxins like amatoxins, can provide an additional layer of safety. However, such kits are not foolproof and should complement, not replace, expert knowledge. If in doubt, the safest approach is to avoid consumption altogether, as even small doses of certain toxins can be fatal.

Comparatively, understanding the differences between toxic and edible brain-like mushrooms is vital. For instance, Hericium erinaceus, or lion’s mane mushroom, has a cascading, brain-like appearance but is not only safe but also prized for its cognitive benefits. Its white, shaggy spines and lack of gills distinguish it from toxic species. Conversely, Phallus ravenelii, or the ravenel’s stinkhorn, has a brain-like cap but emits a putrid smell, making it unappealing and mildly toxic if ingested. By comparing these features—texture, odor, and structural details—foragers can make informed decisions.

Descriptively, the Amanita muscaria, while not brain-like in shape, serves as a cautionary example of a toxic mushroom with a distinctive appearance. Its bright red cap with white spots contrasts sharply with brain mushrooms but shares the danger of misidentification. Similarly, toxic brain mushrooms often exhibit subtle cues, such as a slimy texture or unusual coloration, that set them apart. For example, Mycena species, some of which have brain-like caps, may glow under UV light due to bioluminescence, a feature not present in edible varieties. Observing these details under different lighting conditions can reveal hidden characteristics crucial for identification.

In conclusion, identifying toxic brain mushroom species demands a multi-faceted approach. From analyzing spore prints and habitats to using testing kits and comparing features, each method contributes to safer foraging. Always prioritize caution, as the consequences of misidentification can be severe. With practice and knowledge, distinguishing toxic brain mushrooms becomes less daunting, ensuring both curiosity and safety coexist in the world of mycology.

Vanishing Mushrooms: Are They Poisonous or Just Elusive?

You may want to see also

Safe Cooking Methods for Brain Mushrooms

The brain mushroom, scientifically known as *Gyropus purpurinus*, is not inherently poisonous but requires careful preparation to neutralize its mild toxins. Raw consumption can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort, including nausea and diarrhea, due to the presence of thermolabile compounds that break down with heat. This makes proper cooking essential for safe consumption.

Analytical Insight: The key to rendering brain mushrooms safe lies in their heat sensitivity. Studies show that temperatures above 140°F (60°C) effectively denature the toxins, making thorough cooking a non-negotiable step. Boiling or sautéing for at least 10 minutes ensures complete toxin breakdown, while shorter cooking times may leave residual compounds. This method aligns with traditional practices in regions where brain mushrooms are consumed, such as Eastern Europe and parts of Asia.

Instructive Steps: To safely cook brain mushrooms, start by cleaning them thoroughly under cold water to remove dirt and debris. Slice them into uniform pieces to ensure even heat distribution. For sautéing, heat a tablespoon of oil or butter in a pan over medium heat, add the mushrooms, and cook for 10–12 minutes, stirring occasionally. Alternatively, boiling them in a pot of salted water for 15 minutes works equally well. Always discard the cooking liquid, as it may contain leached toxins.

Comparative Caution: Unlike edible varieties like button or shiitake mushrooms, brain mushrooms cannot be safely consumed raw or lightly cooked. Their toxin profile resembles that of *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane), which also requires heat treatment. However, brain mushrooms are less forgiving—even slightly undercooked specimens can cause adverse reactions. This distinction highlights the importance of precise cooking techniques.

Descriptive Takeaway: Properly cooked brain mushrooms offer a unique, nutty flavor and a meaty texture, making them a worthwhile addition to soups, stews, or stir-fries. Their safety hinges on adherence to heat-based methods, transforming a potentially harmful fungus into a culinary delight. Always err on the side of caution, ensuring thorough cooking to enjoy their benefits without risk.

Are Brown Puffball Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Common Misconceptions About Brain Mushrooms

The brain mushroom, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, is often shrouded in misinformation, leading to dangerous assumptions about its safety. One common misconception is that cooking or drying this mushroom eliminates its toxicity entirely. While heat does break down some of the toxin gyromitrin, it converts into monomethylhydrazine, a compound still harmful in sufficient quantities. Consuming even small amounts of improperly prepared brain mushrooms can lead to severe symptoms, including gastrointestinal distress, seizures, and in extreme cases, organ failure. This highlights the importance of precise preparation methods, such as prolonged boiling and discarding the water, rather than relying solely on cooking to neutralize toxins.

Another widespread myth is that brain mushrooms are safe to eat in small doses. This belief often stems from anecdotal reports of people consuming them without immediate adverse effects. However, toxicity can vary widely depending on factors like the mushroom’s age, growing conditions, and individual sensitivity. For instance, children and the elderly are more susceptible to its toxins due to differences in metabolism. Experts recommend avoiding brain mushrooms altogether, as there is no universally safe dosage. Instead, opt for well-documented edible species like *Boletus edulis* or *Agaricus bisporus* to eliminate risk entirely.

A third misconception is that brain mushrooms can be identified as safe based on appearance alone. While some foragers claim certain characteristics, such as a brain-like cap or reddish-brown color, indicate edibility, these traits are unreliable. Misidentification is a significant risk, as toxic look-alikes like *Gyromitra infula* share similar features. Always cross-reference findings with multiple field guides and, if possible, consult an experienced mycologist. Relying solely on visual cues can lead to accidental poisoning, emphasizing the need for caution and expertise in mushroom foraging.

Lastly, many believe that traditional or folk methods, such as soaking in saltwater or vinegar, can detoxify brain mushrooms. These practices are not scientifically validated and can provide a false sense of security. Gyromitrin is a volatile compound that requires specific treatment to reduce its toxicity effectively. Instead of experimenting with unverified techniques, focus on cultivating or purchasing mushrooms with a well-established safety profile. Prioritizing knowledge and caution over convenience is crucial when dealing with potentially poisonous species like the brain mushroom.

Are Oyster Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Risks and Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Medical Treatment for Brain Mushroom Toxicity

The brain mushroom, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, is indeed poisonous due to its high concentration of gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine in the body. Ingestion can lead to severe symptoms, including gastrointestinal distress, neurological effects, and in extreme cases, organ failure. Immediate medical intervention is crucial to mitigate the toxic effects and prevent long-term damage.

Symptom Management and Decontamination

Upon suspected ingestion, the first step is to remove any remaining mushroom material from the stomach. Activated charcoal, administered within 1–2 hours of consumption, can bind to the toxin and reduce absorption. For patients who present later, gastric lavage (stomach pumping) may be necessary, especially in severe cases. Anti-emetics like ondansetron can control vomiting, while intravenous fluids are essential to maintain hydration and support kidney function, as gyromitrin toxicity can lead to acute kidney injury.

Targeted Medical Interventions

The primary treatment for brain mushroom toxicity involves administering pyridoxine (vitamin B6), which acts as an antagonist to the toxic effects of monomethylhydrazine. A typical adult dose is 25–100 mg/kg intravenously, repeated as needed based on symptom severity. In children, the dosage is adjusted by weight, typically starting at 25 mg/kg. Additionally, benzodiazepines such as diazepam may be used to manage seizures, a potential complication of neurological toxicity.

Supportive Care and Monitoring

Continuous monitoring of vital signs, electrolyte levels, and renal function is critical. Hemodialysis may be required in cases of severe kidney damage or if the patient shows signs of metabolic acidosis. For patients with respiratory distress, supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation may be necessary. Long-term follow-up is recommended to assess for potential neurological or renal sequelae, especially in children and the elderly, who are more susceptible to severe outcomes.

Prevention and Public Awareness

While medical treatment is vital, prevention remains the most effective strategy. Public education campaigns emphasizing the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms, particularly *Gyromitra esculenta*, can reduce accidental poisonings. Proper identification techniques and cooking methods (such as boiling to reduce gyromitrin levels) are often mistakenly believed to make the mushroom safe, but even these methods do not eliminate the risk entirely. When in doubt, avoid consumption and consult a mycologist or poison control center.

Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms for Dogs: A Crucial Guide for Pet Owners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the brain mushroom, also known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, is poisonous if not properly prepared. It contains a toxin called gyromitrin, which can cause severe illness or even death if consumed raw or undercooked.

Symptoms of poisoning include gastrointestinal distress (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), dizziness, headaches, and in severe cases, seizures, liver damage, or coma. Symptoms typically appear within 6–12 hours after consumption.

Brain mushrooms can be made safe for consumption through proper preparation, such as thorough cooking, boiling, or parboiling to remove the gyromitrin toxin. However, even with careful preparation, some people may still experience adverse reactions.

While *Gyromitra esculenta* is the most well-known and toxic species, not all "brain mushrooms" are poisonous. However, it is crucial to accurately identify the species, as misidentification can lead to serious consequences.

Avoid consuming brain mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their identification and proper preparation. If in doubt, consult an experienced forager or mycologist. It’s safer to stick to well-known, non-toxic mushroom species.