Sac fungi, also known as Ascomycota, are a diverse group of fungi characterized by their unique reproductive structures called asci, which are sac-like formations where spores develop. These asci play a crucial role in the life cycle of sac fungi, as they house and nurture the spores until they are ready for dispersal. The development of spores within these structures is a fascinating process that ensures the survival and propagation of the species. Understanding the reproductive mechanisms of sac fungi, particularly the role of asci, provides valuable insights into their ecology, evolution, and significance in various ecosystems. This topic delves into the intricate details of how these reproductive structures function and contribute to the diversity and success of Ascomycota.

What You'll Learn

Sporangia formation and structure

Sporangia, the reproductive structures where spores develop in sac fungi, are marvels of fungal biology. These sac-like organs are the factories where asexual spores, known as sporangiospores, are produced. The formation of sporangia is a tightly regulated process, influenced by environmental cues such as humidity, temperature, and nutrient availability. For instance, in *Zygomycota*, sporangia develop at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores, which elevate the structure to facilitate spore dispersal. This strategic positioning ensures that spores are released into air currents, maximizing their chances of colonizing new habitats.

The structure of sporangia is both simple and ingenious. Typically, they consist of a spherical or oval sac composed of a single layer of cells, within which spores are generated through mitosis. The wall of the sporangium is often thin and delicate, designed to rupture or open upon maturity, releasing the spores. In some fungi, like *Phycomyces*, the sporangium is supported by a long, erect stalk, enhancing its visibility and accessibility to wind currents. The internal organization of sporangia is equally fascinating; spores are often packed tightly but not fused, allowing for easy dispersal once the sporangium opens.

Understanding sporangia formation is crucial for practical applications, particularly in agriculture and pest control. For example, the fungus *Beauveria bassiana* produces sporangia that release spores capable of infecting and controlling insect pests. By optimizing conditions for sporangia formation—such as maintaining a relative humidity of 80–90% and a temperature of 25–30°C—farmers can enhance the efficacy of fungal biocontrol agents. Conversely, disrupting sporangia development in pathogenic fungi can mitigate crop diseases, highlighting the dual importance of this structure in both beneficial and detrimental contexts.

A comparative analysis of sporangia across fungal species reveals remarkable diversity. While *Zygomycota* typically produce large, multicellular sporangia, other groups like *Oomycota* (water molds) form smaller, more delicate structures. This variation reflects adaptations to different environments and dispersal mechanisms. For instance, aquatic fungi often have sporangia with thinner walls to facilitate rapid release in water, whereas terrestrial species may have thicker walls to withstand desiccation. Such adaptations underscore the evolutionary sophistication of sporangia as reproductive tools.

In conclusion, sporangia are not merely passive containers for spores but dynamic structures shaped by environmental and evolutionary pressures. Their formation and structure are finely tuned to ensure efficient spore production and dispersal, making them essential to the life cycle of sac fungi. Whether harnessed for biocontrol or studied for their ecological roles, sporangia offer valuable insights into fungal biology and its applications. Practical tips, such as monitoring environmental conditions and understanding species-specific adaptations, can enhance their utilization in various fields.

Is Spore a Powder Move? Exploring the Debate and Mechanics

You may want to see also

Ascus development in Ascomycota

The Lifecycle of Ascus Development

Ascus formation begins during the sexual phase of the Ascomycota lifecycle. It starts with the fusion of haploid hyphae, known as gametangia, which results in the formation of a diploid zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis to produce haploid nuclei, which then develop into ascospores within the ascus. The ascus itself is a sac-like structure, typically cylindrical or club-shaped, with a thick, resilient wall that protects the developing spores. The number of ascospores per ascus varies among species, ranging from four to eight in most cases, though some fungi may produce up to thousands.

Key Stages and Mechanisms

The development of the ascus involves several distinct stages. First, the ascus wall forms around the meiotic products, creating a confined space for spore maturation. Next, the ascospores undergo a period of growth and differentiation, accumulating nutrients and developing structures like cell walls and pigments. Finally, the mature ascus undergoes a mechanism for spore release, often triggered by environmental cues such as humidity or physical disruption. In some species, the ascus wall ruptures explosively, propelling the spores into the surrounding environment. This process, known as "ascus discharge," maximizes spore dispersal and colonization potential.

Practical Implications and Observations

Understanding ascus development has practical applications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. For instance, many Ascomycota species are plant pathogens, and disrupting ascus formation could be a strategy for disease control. Conversely, beneficial species like *Penicillium* and *Aspergillus* produce valuable compounds like antibiotics and enzymes, making ascus development a target for optimizing biotechnological processes. Observing ascus development under a microscope can also serve as an educational tool, offering insights into fungal biology and the diversity of reproductive strategies in nature.

Comparative Insights and Takeaways

Compared to other fungal groups, such as Basidiomycota, Ascomycota’s ascus-based reproduction is highly efficient and adaptable. The ascus provides a controlled environment for spore development, enhancing survival rates in diverse habitats. This efficiency is reflected in the phylum’s dominance, with Ascomycota comprising over 70% of all described fungal species. By studying ascus development, researchers can uncover evolutionary adaptations that have made Ascomycota one of the most successful fungal groups on Earth. Whether in a laboratory or the wild, the ascus remains a testament to the intricate and elegant mechanisms of fungal reproduction.

Hot Dryer vs. Ringworm Spores: Can Heat Eliminate the Fungus?

You may want to see also

Role of fruiting bodies in spore release

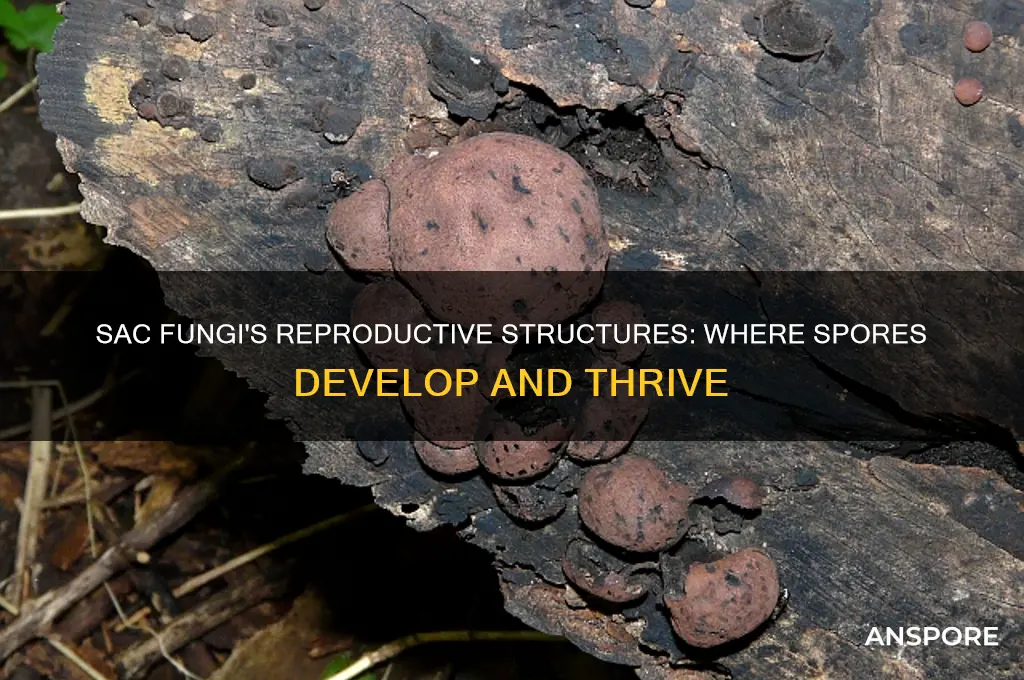

Fruiting bodies, the visible reproductive structures of sac fungi, serve as the primary sites for spore development and release. These structures, often mushroom-like in appearance, are not merely passive containers but dynamic systems optimized for efficient spore dispersal. Within the fruiting body, asci—microscopic, sac-like structures—house the spores, which are ejected with precision and force when conditions are optimal. This mechanism ensures that spores travel beyond the immediate vicinity of the fungus, increasing the likelihood of colonization in new environments.

Consider the process of spore release as a finely tuned biological event. When asci mature, they accumulate turgor pressure, creating a spring-loaded system. Upon triggering, often by environmental cues like humidity or temperature changes, the asci rupture, propelling spores into the air. This explosive release, known as "ballistic discharge," can launch spores several millimeters—a significant distance at the fungal scale. For example, the fungus *Neurospora crassa* uses this method to disperse spores up to 1 centimeter, showcasing the efficiency of fruiting body design.

To maximize spore dispersal, fruiting bodies are strategically positioned and structured. Many fungi grow their fruiting bodies above ground or on elevated substrates, such as decaying wood or plant debris, to take advantage of air currents. The gills, pores, or teeth on the fruiting body’s underside increase surface area, allowing for the simultaneous release of millions of spores. For instance, the common mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* has gills that can release up to 1 billion spores per day under ideal conditions. This design ensures that even if a small fraction of spores land in a suitable habitat, the fungus can successfully propagate.

Practical observations reveal that environmental factors significantly influence fruiting body function. High humidity, for instance, is critical for spore release, as it prevents premature drying and ensures spores remain viable upon ejection. Conversely, excessive moisture can hinder dispersal by causing spores to clump together. Optimal conditions typically include temperatures between 15°C and 25°C and relative humidity above 80%. Gardeners and mycologists can replicate these conditions to encourage fruiting and spore release in cultivated fungi, such as oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), by maintaining controlled environments in grow rooms or greenhouses.

In summary, fruiting bodies are not just reproductive organs but sophisticated dispersal mechanisms. Their structure, positioning, and response to environmental cues work in harmony to ensure spores are released effectively and widely. Understanding these dynamics not only sheds light on fungal biology but also offers practical insights for agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology. By mimicking natural conditions, humans can harness the power of fruiting bodies to cultivate fungi sustainably and study their ecological roles more deeply.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores from Your Carpet Safely

You may want to see also

Sexual vs. asexual spore production

Sac fungi, or Ascomycota, produce spores within specialized structures called asci, which are crucial for their reproductive strategies. These spores can be generated through either sexual or asexual means, each with distinct mechanisms and ecological implications. Understanding the differences between these processes is essential for anyone studying fungal biology or managing fungal populations in agriculture, medicine, or environmental science.

Sexual spore production in sac fungi involves the fusion of gametes from two compatible individuals, leading to genetic recombination. This process begins with the formation of ascogonium (female structure) and antheridium (male structure), which merge to create a zygote. The zygote then undergoes meiosis within the ascus, producing haploid ascospores. This method is advantageous because it generates genetic diversity, enabling populations to adapt to changing environments. For example, *Neurospora crassa*, a model organism in genetics, uses sexual reproduction to create spores with novel traits. However, sexual reproduction requires specific conditions, such as compatible mates and favorable environmental cues, making it less frequent than asexual methods.

In contrast, asexual spore production is a rapid and efficient process that does not involve genetic recombination. Sac fungi often produce asexual spores, called conidia, on structures like conidiophores. These spores are clones of the parent fungus, ensuring consistency in traits but limiting adaptability. Asexual reproduction is favored in stable environments where the parent fungus is already well-suited to survive. For instance, *Aspergillus fumigatus*, a common soil fungus, disperses conidia widely to colonize new habitats quickly. While asexual spores are produced in large quantities, their lack of genetic diversity can make fungal populations vulnerable to sudden environmental changes or diseases.

Practical considerations for managing sac fungi depend on whether they reproduce sexually or asexually. In agriculture, encouraging sexual reproduction in beneficial fungi can enhance their resilience to pests and diseases. For example, introducing compatible strains of *Trichoderma* spp. can promote genetic diversity and improve biocontrol efficacy. Conversely, controlling pathogenic fungi like *Fusarium* spp. often involves disrupting their asexual spore production, such as by reducing humidity or using fungicides. Understanding the reproductive mode of a fungus is also critical in medical settings, as sexual spores of fungi like *Candida albicans* can lead to more severe infections due to their genetic variability.

Takeaway: Sexual and asexual spore production in sac fungi represent contrasting strategies with unique advantages and limitations. Sexual reproduction fosters genetic diversity, enhancing long-term survival, while asexual reproduction allows for rapid proliferation in stable environments. By recognizing these differences, researchers and practitioners can develop targeted strategies to either harness or inhibit fungal growth, depending on the context. Whether in the lab, field, or clinic, this knowledge is indispensable for managing the complex roles of sac fungi in ecosystems and human affairs.

Boiling Water: Effective Method to Kill Spores or Not?

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore maturation

Sac fungi, or Ascomycetes, produce spores within specialized structures called asci, which are crucial for their reproductive cycle. The maturation of these spores is not a random process but is finely tuned to environmental cues that signal optimal conditions for dispersal and germination. Understanding these triggers is essential for both ecological research and practical applications, such as pest control and crop management.

Light and Temperature: The Dual Regulators

Light and temperature act as primary environmental triggers for spore maturation in sac fungi. Many species, like *Neurospora crassa*, exhibit photoperiod sensitivity, where specific light wavelengths accelerate or delay spore development. For instance, red light (660 nm) often promotes maturation, while far-red light (730 nm) can inhibit it. Temperature plays a complementary role; most sac fungi require a temperature range of 20–28°C for optimal spore maturation. Deviations from this range can either halt the process or produce non-viable spores. For example, *Aspergillus nidulans* spores mature efficiently at 25°C but fail to develop properly below 15°C or above 35°C.

Humidity and Nutrient Availability: Fine-Tuning the Process

Humidity levels and nutrient availability are secondary but critical triggers. High humidity (above 80%) is often necessary for ascus formation and spore maturation, as it prevents desiccation during development. In contrast, nutrient depletion, particularly of nitrogen and carbon sources, can signal the fungus to allocate resources to spore production. For instance, *Fusarium graminearum*, a crop pathogen, initiates spore maturation when nitrogen levels in its environment drop below 10 mM. This response ensures spores are produced when the fungus is most likely to find a new host.

Practical Applications and Cautions

Manipulating these environmental triggers can be a powerful tool in agriculture and biotechnology. For example, controlling light exposure and temperature in greenhouses can suppress spore maturation in pathogenic fungi, reducing crop infections. However, caution is necessary; over-reliance on a single trigger, such as temperature, can lead to unintended consequences, like the development of resistant strains. Additionally, while nutrient depletion triggers spore maturation, excessive starvation can lead to abortive development. Researchers and practitioners should adopt a balanced approach, combining multiple triggers to achieve consistent results.

Comparative Insights: Lessons from Nature

Comparing sac fungi with other fungal groups highlights the uniqueness of their response to environmental triggers. Basidiomycetes, for instance, rely more heavily on humidity and physical disturbances for spore release, whereas Ascomycetes prioritize light and nutrient cues. This difference underscores the evolutionary adaptation of sac fungi to specific ecological niches. By studying these variations, scientists can develop targeted strategies for managing fungal populations in diverse environments, from forests to food storage facilities.

Takeaway: Harnessing Triggers for Control

Preserve Your Spore Creations: Easy Email Update Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The reproductive structures where spores develop on sac fungi are called asci (singular: ascus).

Spores, known as ascospores, develop through a process called ascosporogenesis, which occurs inside the ascus following karyogamy (fusion of nuclei) and meiosis.

Asci are crucial for sexual reproduction in sac fungi (Ascomycota), as they protect and disperse ascospores, ensuring genetic diversity and survival in various environments.