The practice of using mushrooms as a means of poisoning or executing prisoners is a fascinating yet dark aspect of ancient civilizations. Among the most notable cultures to employ this method were the ancient Greeks and Romans, who utilized certain toxic mushroom species, such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), to induce slow and agonizing deaths. These mushrooms contain potent toxins like amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage, leading to fatal outcomes. Historical accounts suggest that prisoners were often forced to consume these mushrooms as a form of capital punishment, with the slow-acting nature of the poison serving as a deterrent and a means of psychological torture. This grim practice highlights the ingenuity and cruelty of ancient societies in their use of natural substances for punitive purposes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom Types Used: Ancient civilizations identified toxic fungi species for poisoning prisoners effectively

- Preparation Methods: Mushrooms were dried, powdered, or brewed into lethal concoctions for execution

- Cultural Beliefs: Poisoning was linked to spiritual punishment or divine justice in some societies

- Historical Records: Texts and artifacts document mushroom use in ancient penal practices

- Symptoms and Effects: Victims experienced hallucinations, organ failure, or death from toxic mushrooms

Mushroom Types Used: Ancient civilizations identified toxic fungi species for poisoning prisoners effectively

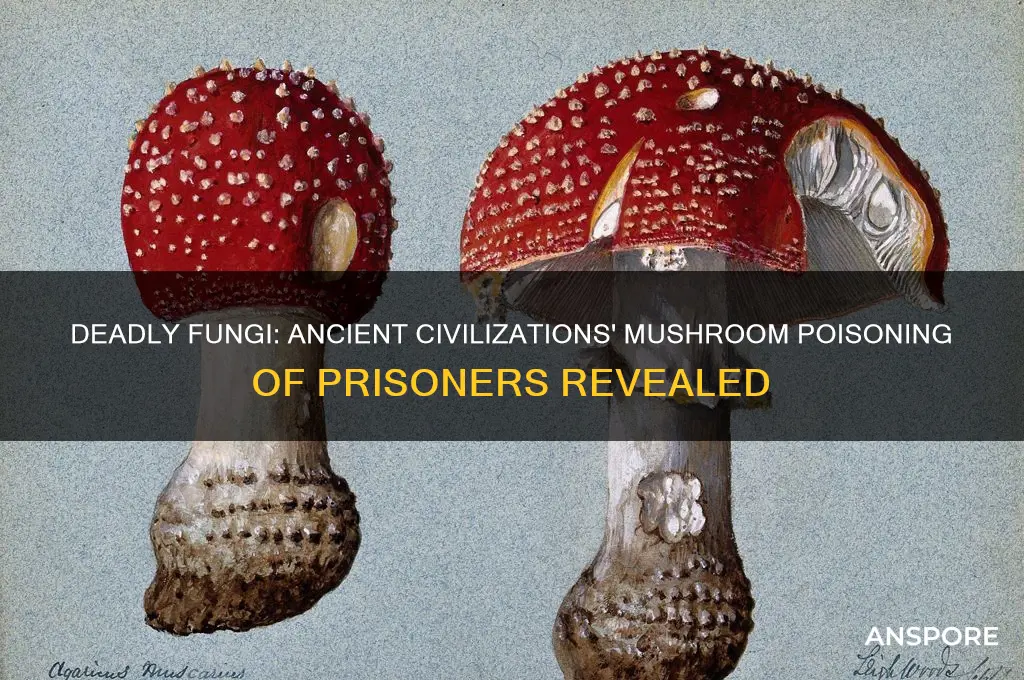

Ancient civilizations, with their intricate knowledge of the natural world, often turned to toxic fungi as a method of poisoning prisoners. Among the myriad of mushroom species, certain varieties were particularly prized for their lethal or incapacitating effects. One such example is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), a fungus notorious for its potent toxins, including alpha-amanitin, which causes severe liver and kidney damage. Historical records suggest that this mushroom was used in executions and assassinations, though its application in prisoner poisoning is less documented. Its delayed onset of symptoms—often 6 to 24 hours after ingestion—made it a cunning choice, as victims would appear unharmed initially, only to succumb later.

Another mushroom of interest is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), a close relative of the Death Cap. Its toxins are equally deadly, targeting the liver and kidneys with relentless efficiency. Ancient cultures likely favored this mushroom for its rapid lethality when consumed in sufficient quantities. A single cap contains enough toxin to kill an adult, making dosage control relatively straightforward. However, its stark white appearance and lack of distinctive odor required careful identification to avoid accidental poisoning of the poisoner.

In contrast, the Fool’s Mushroom (*Clitocybe rivulosa*) offers a different approach to poisoning. Its toxins induce severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting and diarrhea, which could debilitate prisoners without necessarily killing them. This mushroom’s effects are less predictable, as individual tolerance varies, but its widespread availability in Europe made it a practical choice for those seeking to incapacitate rather than execute. Its unassuming appearance—small, white, and easily mistaken for edible species—added to its utility in covert poisoning.

For a more psychological approach, ancient civilizations might have employed the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*). Unlike its deadly cousins, this mushroom contains muscimol and ibotenic acid, which induce hallucinations, confusion, and disorientation. While not typically lethal in small doses, its psychoactive effects could render prisoners compliant or disoriented, making it a tool for control rather than elimination. However, its unpredictable potency and potential for long-term neurological effects required careful administration.

In practice, the choice of mushroom depended on the desired outcome—whether death, debilitation, or control. Dosage was critical, as even toxic species could be harmless in minute quantities. Ancient poisoners likely relied on trial and error, observing symptoms in animals or lower-status individuals before administering the poison to their intended targets. The use of mushrooms in prisoner poisoning highlights the intersection of botany, chemistry, and strategy in ancient warfare and justice systems. Understanding these practices not only sheds light on historical methods but also underscores the enduring danger of toxic fungi in modern contexts.

Are Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Fungus Toxicity

You may want to see also

Preparation Methods: Mushrooms were dried, powdered, or brewed into lethal concoctions for execution

Ancient civilizations often turned to the natural world for tools of punishment, and mushrooms, with their potent toxins, were a favored choice for execution. The preparation of these lethal concoctions was an art as much as it was a science, requiring precision and knowledge of mycology. Drying, powdering, and brewing were the primary methods employed to transform mushrooms into instruments of death. Each technique served a specific purpose, whether it was to concentrate the toxin, mask its presence, or ensure its rapid absorption into the victim’s system.

Drying: Preserving Potency

Drying mushrooms was a common practice to extend their shelf life and intensify their toxic properties. By removing moisture, the active compounds, such as amatoxins found in *Amanita phalloides* (the Death Cap), became more concentrated. This method was particularly useful for civilizations that needed to store poisons for future use. To dry mushrooms effectively, they were often strung on cords and hung in well-ventilated, shaded areas. Once desiccated, the mushrooms could be crushed into a fine powder, making it easier to conceal in food or drink. A single gram of powdered Death Cap, for instance, contains enough toxin to cause severe liver failure in an adult, making dosage both deadly and precise.

Powdering: Stealth and Efficiency

Powdered mushrooms offered a discreet way to administer poison. The fine texture allowed it to be mixed into meals or beverages without detection, ensuring the victim would consume the lethal dose unknowingly. Ancient executioners likely favored this method for its subtlety, as it avoided the need for direct confrontation. However, powdering required careful handling, as inhalation of toxic spores could endanger the preparer. Gloves made from animal hides or thick cloth were often used to protect the hands during this process. A pinch of powdered *Amanita virosa* (the Destroying Angel), another highly toxic species, was sufficient to induce fatal organ failure within hours.

Brewing: Rapid Onset, Certain Death

Brewing mushrooms into a tea or broth was a method favored for its speed and efficacy. Boiling the mushrooms released their toxins into the liquid, creating a potent concoction that could be forced upon the prisoner or administered voluntarily under false pretenses. This technique was particularly useful for executions requiring immediate results, as ingestion of the brew could lead to symptoms within 6 to 24 hours. The dosage was critical; a single cup of *Galerina marginata* (the Funeral Bell) tea contained enough toxin to cause irreversible kidney and liver damage. Brewing also allowed for the addition of other substances to mask the mushroom’s bitter taste, making it more palatable to the unsuspecting victim.

Comparative Analysis: Choosing the Right Method

Each preparation method had its advantages and drawbacks. Drying and powdering were ideal for long-term storage and covert administration but required careful handling to avoid accidental exposure. Brewing, while faster-acting, was less discreet and necessitated immediate use. The choice of method often depended on the context of the execution—whether it was to be public, private, or disguised as an accident. For instance, a powdered toxin might be used in a political assassination, while a brewed concoction could be employed for a swift, public execution. Understanding these techniques offers insight into the calculated brutality of ancient justice systems and their reliance on nature’s most deadly offerings.

Are All Garden Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Finds

You may want to see also

Cultural Beliefs: Poisoning was linked to spiritual punishment or divine justice in some societies

In certain ancient societies, poisoning was not merely a physical act but a spiritual one, deeply intertwined with beliefs about divine justice and moral retribution. For instance, some cultures viewed toxic substances, including mushrooms, as tools of the gods to punish wrongdoing. This perspective transformed the act of poisoning prisoners from a simple execution into a ritualistic act of cosmic balance. The choice of mushrooms, with their dual nature as both healer and poison, added layers of symbolic meaning, suggesting that the punishment was not arbitrary but divinely ordained.

Consider the analytical perspective: the use of mushrooms in poisoning prisoners often reflected a society’s worldview, where illness and death were seen as consequences of spiritual imbalance. In such cultures, administering poisonous mushrooms to prisoners was not just a means of ending life but a way to restore harmony in the universe. For example, a specific dosage of Amanita muscaria, a psychoactive mushroom, might be given to induce hallucinations, symbolizing the prisoner’s journey into the afterlife or their confrontation with divine judgment. This practice was less about the physical suffering and more about aligning the act with spiritual principles.

From an instructive standpoint, if one were to explore this practice, it’s crucial to understand the cultural context. For instance, in some Mesoamerican societies, mushrooms like Psilocybe were associated with deities and used in rituals to communicate with the divine. Poisoning prisoners with such mushrooms could be seen as a way to force a spiritual reckoning, ensuring the individual faced divine justice before death. Practical tips for understanding this include studying the specific mushroom species used, their effects, and the rituals surrounding their administration. For example, a small dose of Psilocybe might induce visions, while a larger dose could be lethal, with the choice of dosage reflecting the severity of the crime.

A comparative analysis reveals that while some cultures used poisoning as a form of divine justice, others viewed it as a means of purification. In certain European traditions, mushrooms like the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) were associated with dark forces, and poisoning prisoners with them was seen as a way to expel evil from the community. This contrasts with societies that believed the poisoned individual’s spirit would be cleansed in the afterlife, ensuring they did not carry their sins into the next world. Such variations highlight the diversity of cultural beliefs surrounding poisoning as spiritual punishment.

Finally, a descriptive approach paints a vivid picture of these practices. Imagine a ritual where a prisoner is given a concoction of poisonous mushrooms under the watchful eyes of priests or shamans. The air is thick with incense, and chants echo the belief that the act is not mere execution but a sacred duty. The prisoner’s reaction—whether convulsions, hallucinations, or a serene acceptance—is interpreted as evidence of divine intervention. This scene underscores the profound connection between poisoning, spirituality, and justice in these ancient societies, offering a glimpse into how cultural beliefs shaped even the most final of acts.

Poisonous Mushrooms in Ireland: Identifying Risks and Staying Safe

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.99 $26.99

Historical Records: Texts and artifacts document mushroom use in ancient penal practices

Ancient texts and artifacts reveal a chilling practice: the use of mushrooms as a tool of punishment and execution. Among the most compelling evidence is the Ebers Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical text dating to around 1550 BCE. While primarily focused on remedies, it obliquely references toxic fungi as a means of inducing severe illness or death. Though not explicitly tied to penal practices, its inclusion of mushroom-based poisons suggests their potential use in judicial contexts. Similarly, Mesopotamian clay tablets from the Code of Hammurabi era (1754 BCE) allude to "plants of the earth" causing harm, a phrase scholars speculate could include hallucinogenic or toxic mushrooms. These records, though cryptic, hint at a deliberate application of fungi in ancient justice systems.

Artifacts further corroborate this grim practice. In ancient Greece, archaeological excavations at Delphi uncovered ceramic vessels containing traces of *Clitocybe dealbata*, a mushroom known to cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in high doses, organ failure. Inscriptions on these vessels suggest they were used in rituals, but their proximity to judicial sites implies a dual purpose—administering poison to prisoners under the guise of divine judgment. Similarly, Roman historian Pliny the Elder documented in his *Naturalis Historia* that certain tribes in Gaul used *Amanita muscaria* to execute criminals, noting its ability to induce convulsions and death within hours. These accounts, while scattered, paint a consistent picture of mushrooms as instruments of penal retribution.

Dosage and administration methods were critical to ensuring the desired effect. Ancient practitioners likely relied on trial and error, with texts like the Chinese *Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing* (circa 200 CE) detailing precise quantities of toxic mushrooms for different outcomes. For instance, a single cap of *Amanita phalloides* could cause fatal liver failure within 48 hours, while smaller doses of *Coprinus atramentarius* induced vomiting and disorientation—a punishment for lesser crimes. Age and health were also considered; younger prisoners were often given lower doses to prolong suffering, while the elderly received higher amounts for swift execution. These meticulous instructions underscore the calculated nature of mushroom-based penalties.

Comparatively, the use of mushrooms in penal practices contrasts with their role in spiritual or medicinal contexts. While cultures like the Maya and Aztecs revered psychoactive mushrooms for their hallucinogenic properties, their application in punishment was distinctly secular and punitive. This duality highlights the versatility of fungi in ancient societies—a tool of both enlightenment and torment. By examining these records, we gain insight into the sophistication of ancient justice systems and their willingness to exploit nature’s deadliest creations. Practical takeaways for modern scholars include cross-referencing botanical and historical sources to identify specific mushroom species and their effects, ensuring accurate interpretation of ancient practices.

Are Brown Yard Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Safe Identification

You may want to see also

Symptoms and Effects: Victims experienced hallucinations, organ failure, or death from toxic mushrooms

The use of toxic mushrooms as a method of poisoning prisoners in ancient civilizations highlights a chilling intersection of botany and punishment. Victims subjected to this practice often experienced a range of symptoms, from psychological torment to fatal physiological collapse. Hallucinations, induced by psychoactive compounds like psilocybin or muscimol, were among the earliest signs, disorienting prisoners and stripping them of their mental defenses. These altered states were not merely inconvenient—they were deliberate tools of control, rendering victims compliant or incoherent. However, the true danger lay in the toxic varieties, such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which contains amatoxins capable of causing irreversible organ failure within 24 to 48 hours. A single mushroom, weighing as little as 30 grams, contains enough toxin to be lethal if ingested, making dosage a matter of life and death.

Understanding the progression of symptoms is critical for recognizing mushroom poisoning, whether in historical contexts or modern scenarios. Initial signs often mimic gastrointestinal distress—nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—which can be mistaken for a simple stomach bug. However, these symptoms are the body’s attempt to expel the toxin, a futile effort against amatoxins, which begin damaging the liver and kidneys within hours. As organ failure sets in, victims may experience jaundice, confusion, and seizures, culminating in death if untreated. In ancient settings, where medical intervention was nonexistent, such poisoning was a slow, agonizing execution disguised as a natural illness. The lack of antidote knowledge ensured that even small doses could be fatal, making mushrooms a silent yet effective weapon.

From a comparative perspective, the symptoms of mushroom poisoning contrast sharply with other ancient execution methods, such as beheading or crucifixion, which were immediate and public. Mushroom poisoning, however, was insidious and private, often leaving no visible marks on the victim. This stealthy approach served dual purposes: it maintained the illusion of natural death, shielding the perpetrators from accusations of cruelty, while also instilling fear in surviving prisoners. The unpredictability of symptoms—hallucinations followed by organ failure—added a psychological layer to the punishment, as victims were left to question their sanity before facing physical collapse. This duality of mental and physical suffering underscores the sophistication of using mushrooms as a tool of retribution.

Practical awareness of toxic mushrooms remains relevant today, as accidental ingestion still poses a significant risk. For instance, the Death Cap resembles edible varieties like the Paddy Straw mushroom, leading to frequent misidentification. To avoid such dangers, adhere to the rule: never consume a wild mushroom unless identified by an expert. If poisoning is suspected, immediate medical attention is crucial, as early administration of activated charcoal or silibinin (a liver-protecting compound) can mitigate damage. While ancient civilizations exploited mushrooms for their lethal potential, modern knowledge allows us to respect their power while minimizing risk. Recognizing the symptoms—hallucinations, organ failure, or death—serves as a stark reminder of both their historical use and contemporary hazards.

Amanita Mushrooms and Dogs: Toxicity Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some ancient civilizations, such as the Greeks and Romans, were known to use poisonous mushrooms to execute or harm prisoners.

The *Amanita phalloides*, also known as the Death Cap mushroom, was frequently used due to its high toxicity and lethal effects.

Poisonous mushrooms were often mixed into food or drink, making it difficult for prisoners to detect and avoid ingestion.

No, mushrooms were one of several methods used, alongside more common practices like beheading, crucifixion, or poisoning with other substances.

Many ancient civilizations had a deep understanding of mushroom toxicity, as evidenced by historical texts like those of Greek philosopher Theophrastus, who documented poisonous fungi.