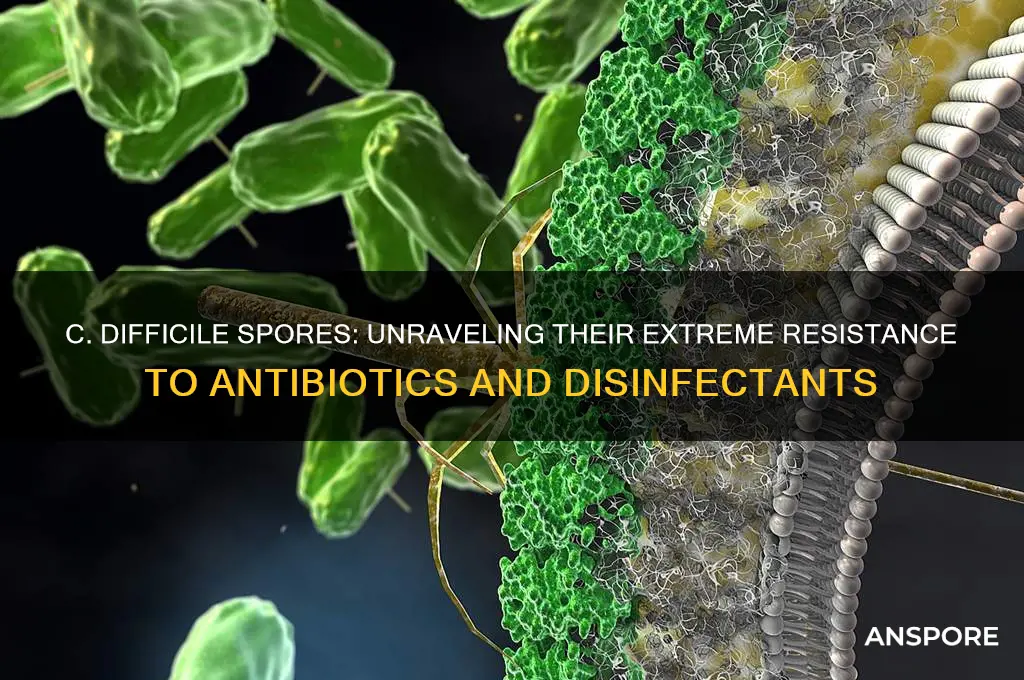

*Clostridioides difficile* (C. difficile) spores are highly resistant to a variety of environmental stressors, making them particularly challenging to eradicate. These spores can withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and many common disinfectants, including alcohol-based cleaners. Their resistance is attributed to their robust outer coat, which protects the spore’s genetic material and metabolic machinery. Additionally, C. difficile spores are highly resistant to antibiotics, as the dormant spore form is not affected by many antimicrobial agents that target actively growing bacteria. This resilience allows the spores to persist in healthcare settings, on surfaces, and in the environment for extended periods, contributing to their role as a leading cause of healthcare-associated infections. Understanding the mechanisms behind this resistance is crucial for developing effective strategies to control and prevent C. difficile transmission.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heat | Highly resistant to temperatures up to 70°C (158°F) for prolonged periods; can survive autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 15–30 minutes if not properly sterilized |

| Desiccation | Can survive in dry environments for months to years |

| Disinfectants | Resistant to many common disinfectants, including alcohol-based products; requires spore-specific agents like chlorine-based disinfectants (e.g., 5,000–10,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite) |

| Antibiotics | Not directly affected by most antibiotics, as spores are dormant and lack metabolic activity; antibiotics target vegetative cells |

| UV Light | Highly resistant to ultraviolet (UV) light exposure |

| pH Levels | Tolerant to a wide range of pH levels, from acidic to alkaline environments |

| Oxygen | Anaerobic in nature but spores are resistant to oxygen exposure |

| Radiation | Resistant to low levels of ionizing radiation |

| Chemical Agents | Resistant to many chemical agents, including quaternary ammonium compounds and phenolic disinfectants |

| Environmental Persistence | Can persist on surfaces and in soil for extended periods, contributing to transmission |

What You'll Learn

- Antibiotics: C. difficile spores survive most antibiotics, persisting in the gut after treatment

- Heat: Spores withstand temperatures up to 70°C, resisting typical disinfection methods

- Desiccation: Highly resistant to drying, allowing long-term survival in harsh environments

- Chemicals: Tolerate disinfectants like alcohol, requiring spore-specific cleaning agents for eradication

- Radiation: Spores resist UV light and low doses of ionizing radiation, ensuring survival

Antibiotics: C. difficile spores survive most antibiotics, persisting in the gut after treatment

C. difficile spores are notorious for their resilience, particularly in the face of antibiotic treatment. Unlike many bacteria that succumb to these drugs, C. difficile spores can withstand the onslaught, remaining dormant and unscathed in the gut even after a full course of antibiotics. This survival mechanism is a key factor in the recurrence of C. difficile infections (CDIs), which affect nearly 20% of patients, often within weeks of initial treatment. The spores’ ability to evade antibiotics lies in their robust outer coating, which protects the bacterial DNA from the drugs’ effects. This persistence highlights a critical challenge in managing CDIs: while antibiotics target actively growing bacteria, they are largely ineffective against the dormant spore form.

Consider the typical scenario: a patient receives a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as clindamycin or fluoroquinolones, to treat a bacterial infection. These antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiome, killing beneficial bacteria that normally keep C. difficile in check. The spores, however, remain unaffected, biding their time until conditions are favorable for germination. Once the antibiotic course ends, the spores activate, multiply, and produce toxins that cause symptoms like diarrhea and inflammation. This cycle underscores why antibiotics, while essential for treating infections, can inadvertently create an environment ripe for C. difficile overgrowth.

To mitigate this risk, healthcare providers must adopt a strategic approach to antibiotic use. For instance, narrow-spectrum antibiotics should be prioritized over broad-spectrum options whenever possible, as they target specific pathogens without causing widespread disruption to the gut flora. Additionally, antibiotic stewardship programs—which promote appropriate prescribing practices—are crucial in reducing the incidence of CDIs. For patients at high risk, such as the elderly or those with compromised immune systems, probiotics or fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) may be considered to restore gut balance after antibiotic treatment.

A practical tip for patients is to question the necessity of antibiotics before starting a course. For example, antibiotics are often overprescribed for viral infections like colds or flu, where they have no effect. By avoiding unnecessary use, individuals can lower their risk of disrupting their gut microbiome and triggering a C. difficile infection. Similarly, healthcare providers should educate patients about the signs of CDI recurrence, such as persistent diarrhea or abdominal pain, to ensure prompt treatment if symptoms reappear.

In conclusion, the survival of C. difficile spores in the presence of antibiotics is a testament to their evolutionary adaptability. While antibiotics remain a cornerstone of modern medicine, their use must be balanced with an understanding of the unintended consequences they can have on the gut microbiome. By adopting targeted prescribing practices, exploring alternative treatments, and fostering patient awareness, we can reduce the burden of CDIs and improve outcomes for those at risk. This nuanced approach is essential in the ongoing battle against this resilient pathogen.

How Low Should a Sporran Hang? A Guide to Proper Placement

You may want to see also

Heat: Spores withstand temperatures up to 70°C, resisting typical disinfection methods

C. difficile spores are remarkably resilient to heat, enduring temperatures up to 70°C without losing viability. This resistance poses a significant challenge in healthcare settings, where standard disinfection methods often rely on heat to eliminate pathogens. For instance, autoclaving, a common sterilization technique, typically operates at 121°C, but C. difficile spores can survive lower temperatures commonly used in surface disinfection or laundry processes. This survival capability underscores the need for more rigorous protocols to ensure complete eradication.

Consider the practical implications for infection control. Standard hot water washing cycles, which rarely exceed 60°C, are insufficient to kill C. difficile spores. Even industrial dishwashers, often used in healthcare facilities, may not reach the necessary temperatures to ensure spore inactivation. This highlights the importance of supplementing heat-based methods with additional measures, such as chemical disinfectants proven effective against spores, to mitigate transmission risks.

From a comparative perspective, the heat resistance of C. difficile spores contrasts sharply with other bacterial spores, such as those of Bacillus species, which are often used as benchmarks for disinfection efficacy. While Bacillus spores require prolonged exposure to temperatures above 100°C for inactivation, C. difficile spores’ tolerance to 70°C makes them a unique threat in environments where lower heat treatments are applied. This distinction necessitates tailored strategies for C. difficile control, emphasizing the limitations of heat-dependent methods.

To address this challenge, healthcare facilities should adopt a multi-faceted approach. First, ensure that laundry and cleaning processes incorporate temperatures exceeding 70°C where possible. Second, use spore-specific disinfectants, such as chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 5,000–10,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite), in conjunction with heat treatments. Finally, educate staff on the risks of relying solely on heat, particularly in settings where temperatures may not reach the critical threshold. By combining these measures, the persistence of C. difficile spores can be effectively managed, reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections.

Mastering Moss Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Moss from Spores

You may want to see also

Desiccation: Highly resistant to drying, allowing long-term survival in harsh environments

C. difficile spores are remarkably resilient to desiccation, a trait that enables them to persist in dry environments for extended periods. This resistance is a key factor in their ability to survive outside the host, often contaminating surfaces in healthcare settings and posing a significant infection risk. Unlike many other bacteria, which require moisture to remain viable, C. difficile spores can endure extreme dryness, making them challenging to eradicate through conventional cleaning methods.

The mechanism behind this resistance lies in the spore’s structure. C. difficile spores have a thick, multilayered coat that acts as a protective barrier against environmental stressors, including desiccation. This coat is composed of proteins and peptides that minimize water loss and maintain the spore’s internal integrity. Additionally, the spore’s core contains highly concentrated DNA and enzymes in a dehydrated state, further enhancing its ability to withstand drying. These adaptations allow the spores to remain dormant yet viable for months or even years, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate and cause infection.

Practical implications of this resistance are significant, particularly in healthcare settings. Standard disinfection protocols often rely on moisture-based cleaning agents, which are ineffective against desiccation-resistant spores. To combat this, facilities must employ spore-specific disinfectants, such as chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 1,000–5,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite), which can penetrate the spore coat and inactivate the organism. Surfaces should be thoroughly wetted and allowed to remain in contact with the disinfectant for at least 10 minutes to ensure efficacy. Regular environmental testing for C. difficile spores can also help identify high-risk areas and guide targeted cleaning efforts.

For individuals at risk, particularly those in healthcare or long-term care facilities, understanding this resistance is crucial for prevention. Hand hygiene with soap and water is more effective than alcohol-based sanitizers, as the latter does not eliminate spores. Patients and caregivers should also be educated on the importance of cleaning high-touch surfaces, such as bed rails and doorknobs, with spore-killing agents. In home settings, laundering contaminated fabrics with bleach and hot water (at least 60°C) can reduce spore transmission.

In summary, the desiccation resistance of C. difficile spores underscores the need for tailored disinfection strategies. By recognizing the limitations of traditional cleaning methods and adopting spore-specific practices, healthcare providers and individuals can mitigate the risk of infection and break the chain of transmission. This knowledge is not just theoretical but a practical tool in the ongoing fight against C. difficile-associated diseases.

How Long Do Black Mold Spores Remain Airborne: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Chemicals: Tolerate disinfectants like alcohol, requiring spore-specific cleaning agents for eradication

C. difficile spores present a unique challenge in healthcare settings due to their remarkable resistance to common disinfectants, particularly alcohol-based solutions. This resilience necessitates a shift from standard cleaning protocols to specialized strategies. Alcohol, a staple in disinfection routines, is ineffective against these spores because it fails to penetrate their robust outer coating. This biological armor allows the spores to survive exposure to concentrations of ethanol and isopropanol that would readily inactivate other pathogens. As a result, healthcare facilities must adopt alternative cleaning agents specifically designed to target and eradicate C. difficile spores.

The ineffectiveness of alcohol-based disinfectants highlights the importance of selecting spore-specific cleaning agents. Chlorine-based compounds, such as sodium hypochlorite (bleach), are among the most effective options. A solution of 1,000–5,000 parts per million (ppm) of available chlorine is recommended for surface disinfection. For example, a 1:10 dilution of household bleach (typically 5% sodium hypochlorite) in water achieves an effective concentration of 5,000 ppm. However, it’s crucial to follow manufacturer guidelines and ensure proper ventilation when using these agents, as they can be corrosive and irritating. Additionally, hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants, particularly those with accelerated hydrogen peroxide, have demonstrated efficacy against C. difficile spores and are less damaging to surfaces compared to chlorine-based solutions.

Implementing spore-specific cleaning agents requires careful consideration of application methods and contact times. For instance, surfaces contaminated with C. difficile spores should be pre-cleaned to remove organic matter before applying the disinfectant. This step ensures maximum contact between the cleaning agent and the spores. Contact times vary depending on the product; chlorine-based solutions typically require 1–10 minutes, while hydrogen peroxide-based products may need 5–30 minutes. Adhering to these guidelines is essential for achieving complete spore eradication. Failure to do so can result in persistent contamination, increasing the risk of healthcare-associated infections.

While spore-specific cleaning agents are critical, their use must be complemented by proper training and adherence to infection control protocols. Staff should be educated on the limitations of alcohol-based disinfectants and the necessity of using alternative agents for C. difficile. Regular audits of cleaning practices can help identify gaps and ensure compliance. Furthermore, environmental monitoring, such as spore testing, can provide objective data on the effectiveness of cleaning protocols. By combining the right chemicals with rigorous practices, healthcare facilities can mitigate the risk of C. difficile transmission and protect vulnerable patient populations.

Can Fungi Reproduce Without Spores? Exploring Alternative Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Radiation: Spores resist UV light and low doses of ionizing radiation, ensuring survival

C. difficile spores are remarkably resilient to radiation, a trait that significantly contributes to their survival in harsh environments. Unlike many microorganisms, these spores can withstand ultraviolet (UV) light, a common disinfectant used in healthcare settings. UV light, typically emitted at wavelengths of 254 nanometers, is effective against vegetative bacteria but fails to penetrate the robust spore coat of C. difficile. This resistance allows spores to persist on surfaces even after UV disinfection, posing a persistent risk of transmission.

Ionizing radiation, another form of radiation used for sterilization, also struggles to eliminate C. difficile spores at low doses. Studies show that doses below 10 kGy (kilogray) are insufficient to inactivate these spores, while higher doses, often above 25 kGy, are required for complete eradication. This resistance is attributed to the spore’s DNA-protecting mechanisms, including the presence of small, acid-soluble spore proteins (SASPs) that bind to and stabilize DNA, shielding it from radiation-induced damage.

Practical implications of this resistance are significant, particularly in healthcare and food processing industries. For instance, UV disinfection systems, commonly used in hospitals to reduce surface contamination, may not effectively target C. difficile spores. Similarly, low-dose radiation treatments used in food preservation or medical device sterilization may fail to eliminate these spores, necessitating alternative methods like high-temperature treatment or chemical disinfectants.

To combat this resistance, facilities must adopt a multi-pronged approach. Combining UV light with chemical agents like chlorine or hydrogen peroxide can enhance disinfection efficacy. In radiation-based sterilization, ensuring doses exceed 25 kGy is critical for spore inactivation. Additionally, regular monitoring of surfaces and equipment for spore presence can help identify and mitigate risks before outbreaks occur. Understanding and addressing this resistance is essential for controlling C. difficile infections and ensuring public safety.

Strangling Spores: Lethal Threat or Harmless Fungus for Creatures?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

C. difficile spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation (drying), and many disinfectants, including alcohol-based cleaners.

C. difficile spores are highly resistant to routine cleaning methods and can survive on surfaces for weeks or even months, making them challenging to eradicate in healthcare environments.

C. difficile spores are highly resistant to alcohol-based disinfectants but can be effectively killed by spore-specific agents like chlorine-based cleaners (e.g., bleach) or hydrogen peroxide-based products.