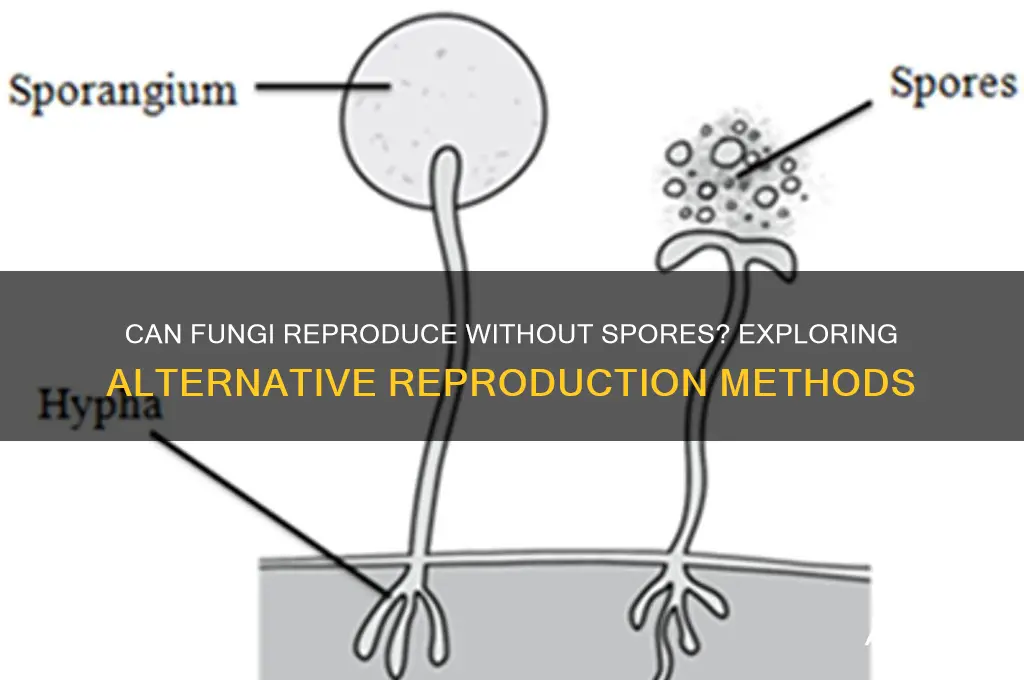

Fungi are a diverse group of organisms primarily known for their ability to reproduce through spores, which are lightweight, resilient structures that disperse and germinate under favorable conditions. However, not all fungi rely solely on spores for reproduction. Some species have evolved alternative methods, such as fragmentation, where parts of the fungal body break off and grow into new individuals, or through the production of specialized structures like sclerotia, which are hardened masses of mycelium that can survive harsh conditions and regenerate. Additionally, certain fungi can reproduce asexually via budding or the formation of vegetative structures like hyphae. These alternative reproductive strategies highlight the adaptability and complexity of fungal life cycles, raising intriguing questions about the conditions under which spore-independent reproduction occurs and its ecological significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Primary Reproduction Method | Most fungi primarily reproduce via spores (sexual or asexual). |

| Alternative Reproduction Methods | Yes, some fungi can reproduce without spores through vegetative means. |

| Vegetative Reproduction Methods | Fragmentation, budding, hyphal fusion, and production of specialized structures like sclerotia or rhizomorphs. |

| Fragmentation | Fungal hyphae break into fragments, each capable of growing into a new individual. |

| Budding | A small outgrowth (bud) develops on the parent fungus and eventually detaches to form a new individual (e.g., yeast). |

| Hyphal Fusion | Hyphae from compatible individuals fuse, sharing genetic material and resources (e.g., in mycelial networks). |

| Sclerotia and Rhizomorphs | Specialized structures that can survive harsh conditions and grow into new fungal colonies (e.g., in mushrooms and molds). |

| Parasexual Cycle | A form of genetic recombination without traditional sexual spores, involving hyphal fusion and exchange of genetic material. |

| Examples of Fungi | Yeasts (budding), molds (fragmentation), and some basidiomycetes (rhizomorphs). |

| Environmental Factors | Vegetative reproduction is more common in stable environments where spores are not necessary for dispersal. |

| Significance | Allows fungi to persist and spread even in conditions unfavorable for spore production or dispersal. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Vegetative Reproduction Methods: Fungi use fragmentation, budding, or hyphal fusion to reproduce without spores

- Role of Mycelium: Mycelial networks enable asexual reproduction through growth and division

- Yeast Budding Process: Yeasts reproduce by budding, forming new cells without spore formation

- Hyphal Fragmentation: Broken hyphae regrow into new fungal individuals independently

- Parasexual Reproduction: Genetic recombination occurs without spores via hyphal fusion and nuclear exchange

Vegetative Reproduction Methods: Fungi use fragmentation, budding, or hyphal fusion to reproduce without spores

Fungi, often associated with spore production, possess a lesser-known yet fascinating ability to reproduce without them. This asexual mode, known as vegetative reproduction, involves the direct transfer of genetic material, bypassing the need for spore formation. Three primary methods dominate this process: fragmentation, budding, and hyphal fusion, each offering unique advantages and contributing to the remarkable adaptability of fungi.

Unlike spore-based reproduction, which relies on dispersal and germination, vegetative reproduction allows fungi to expand their colonies rapidly and efficiently within a localized environment. This is particularly advantageous in stable, resource-rich habitats where establishing a foothold is more crucial than colonizing new territories.

Fragmentation: Breaking Apart to Multiply

Imagine a fungal mycelium, a network of thread-like structures, as a living tapestry. Fragmentation involves the breaking of this tapestry into smaller pieces, each capable of developing into a new, genetically identical individual. This method is akin to cutting a plant stem and rooting the cuttings. For example, certain mushroom-forming fungi, like *Schizophyllum commune*, readily fragment their mycelia, allowing them to spread across decaying wood surfaces. This process is highly efficient, as it requires minimal energy investment and allows for rapid colonization of suitable substrates.

However, fragmentation is not without its limitations. The success of this method depends heavily on the environment. Fragmented pieces must land in suitable conditions with adequate nutrients and moisture to survive and grow.

Budding: A Miniature Clone Factory

Budding, a process reminiscent of yeast reproduction, involves the outgrowth of a small protuberance, or bud, from the parent cell. This bud gradually enlarges, develops its own nucleus and cytoplasm, and eventually detaches, forming a new, genetically identical individual. This method is common in unicellular fungi like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the baker's yeast, where budding allows for rapid population growth in nutrient-rich environments.

The efficiency of budding lies in its simplicity. It requires minimal energy and resources, making it ideal for fungi thriving in environments with abundant nutrients. However, like fragmentation, budding is limited to localized growth and is susceptible to environmental fluctuations.

Hyphal Fusion: A Network of Sharing and Survival

Hyphal fusion, a unique feature of filamentous fungi, involves the merging of hyphae from different individuals, forming a interconnected network. This fusion allows for the exchange of genetic material, nutrients, and even organelles, promoting cooperation and survival within the fungal colony.

This method is particularly advantageous in nutrient-limited environments. By sharing resources, fungi can overcome individual limitations and thrive collectively. Furthermore, hyphal fusion facilitates genetic diversity through the exchange of nuclei, potentially enhancing the colony's adaptability to changing conditions.

In conclusion, vegetative reproduction through fragmentation, budding, and hyphal fusion showcases the remarkable adaptability and resourcefulness of fungi. These methods, while less publicized than spore production, play a crucial role in fungal survival and proliferation, particularly in specific ecological niches. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens our appreciation for the complexity of fungal life but also highlights the diverse strategies employed by organisms to thrive in their environments.

Are Dead Mold Spores Dangerous? Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks

You may want to see also

Role of Mycelium: Mycelial networks enable asexual reproduction through growth and division

Fungi are remarkably versatile organisms, and their reproductive strategies extend beyond the well-known spore-based methods. One such strategy involves the mycelium, a network of thread-like structures that form the vegetative part of a fungus. Mycelial networks play a crucial role in asexual reproduction, enabling fungi to propagate through growth and division without relying on spores. This process is not only efficient but also allows fungi to adapt and thrive in diverse environments.

Consider the mechanism of mycelial fragmentation, a key aspect of this reproductive strategy. When a mycelial network grows, it can divide into smaller fragments, each capable of developing into a new individual fungus. This fragmentation occurs naturally as the mycelium extends through its substrate, whether it’s soil, wood, or other organic matter. For example, in species like *Neurospora crassa*, mycelial fragments can regenerate into fully functional colonies, demonstrating the resilience and adaptability of this method. To encourage this process in a controlled setting, such as in mushroom cultivation, ensure the substrate is nutrient-rich and maintain optimal humidity levels (around 60-70%) to support mycelial growth and fragmentation.

The advantages of mycelial reproduction are particularly evident in resource-limited environments. Unlike spore production, which requires energy-intensive processes, mycelial growth and division are continuous and less resource-demanding. This makes it an ideal strategy for fungi colonizing stable habitats, such as decaying logs or forest floors. For instance, the mycelium of *Armillaria* species can spread over large areas, forming extensive networks that persist for decades, reproducing asexually through fragmentation. This longevity and efficiency highlight the mycelium’s role as a survival mechanism, ensuring fungal persistence even in the absence of spore dispersal.

However, it’s essential to distinguish between mycelial reproduction and other asexual methods. While fragmentation is a form of asexual reproduction, it differs from processes like budding or hyphal tip growth. Fragmentation relies on the physical division of an existing network, whereas budding involves the formation of new individuals from specialized structures. To observe this distinction, examine cultures of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (a budding yeast) alongside mycelial fungi like *Aspergillus*. The yeast will produce buds, while the mycelium will fragment, illustrating the unique nature of each reproductive strategy.

In practical applications, understanding mycelial networks can enhance fungal cultivation and conservation efforts. For mushroom growers, promoting healthy mycelial growth through proper substrate preparation and environmental control can increase yields without relying solely on spore inoculation. Additionally, in ecological restoration, recognizing the role of mycelial networks in soil health can inform strategies for enhancing biodiversity and nutrient cycling. By focusing on the mycelium’s ability to reproduce asexually, we gain insights into fungi’s resilience and their potential to adapt to changing environments. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also opens avenues for harnessing their capabilities in agriculture, ecology, and beyond.

Can You Use Bonemeal on Spore Blossoms? A Minecraft Guide

You may want to see also

Yeast Budding Process: Yeasts reproduce by budding, forming new cells without spore formation

Fungi are remarkably diverse in their reproductive strategies, and while many rely on spores, some, like yeasts, have evolved alternative methods. Among these, the yeast budding process stands out as a fascinating example of asexual reproduction that bypasses spore formation entirely. This mechanism allows yeasts to proliferate rapidly under favorable conditions, making them highly adaptable organisms in various environments, from natural ecosystems to industrial settings.

The budding process begins with a small outgrowth, or bud, forming on the parent cell. This bud gradually increases in size as it receives cytoplasm and organelles from the parent. Crucially, the nucleus of the parent cell undergoes mitosis, producing a daughter nucleus that migrates into the bud. Once the bud reaches a critical size and the daughter nucleus is fully established, it separates from the parent cell, becoming a new, genetically identical individual. This method ensures efficient reproduction without the energy-intensive production of spores, making it particularly advantageous in nutrient-rich environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding yeast budding is essential for industries such as baking, brewing, and biotechnology. For instance, in baking, the budding process of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) is harnessed to leaven dough, with optimal conditions (e.g., temperatures between 25–30°C and a sugar concentration of 5–10%) promoting rapid cell division. Similarly, in brewing, controlling budding rates ensures consistent fermentation. However, excessive budding can lead to overcrowding and resource depletion, so monitoring cell density (ideally below 10^7 cells/mL for most applications) is critical to maintaining productivity.

Comparatively, spore-based reproduction in fungi like molds and mushrooms involves a more complex life cycle, often requiring environmental triggers such as stress or nutrient scarcity. In contrast, yeast budding is a streamlined process that occurs continuously in the presence of adequate resources. This simplicity underscores why yeasts dominate in controlled environments, where conditions can be optimized for their growth. For hobbyists or professionals working with yeasts, maintaining a balanced nutrient supply (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, and vitamins) and avoiding contaminants ensures uninterrupted budding.

In conclusion, the yeast budding process exemplifies how fungi can thrive without relying on spores, offering a unique lens into the adaptability of microbial life. By focusing on this mechanism, industries and researchers can optimize yeast-based processes, from food production to biofuel development. Whether you’re a baker perfecting your sourdough or a scientist culturing yeast in a lab, mastering the nuances of budding is key to harnessing the full potential of these remarkable organisms.

Understanding Fungal Spores: Tiny Reproductive Units and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Hyphal Fragmentation: Broken hyphae regrow into new fungal individuals independently

Fungi are remarkably adaptable organisms, and their reproductive strategies extend beyond the well-known spore formation. One such method, hyphal fragmentation, showcases the resilience and ingenuity of fungal life cycles. When a hypha—the filamentous structure that makes up the fungal body—breaks, the resulting fragments can independently regenerate into new, fully functional individuals. This process is not merely a survival mechanism but a sophisticated form of asexual reproduction that ensures fungal proliferation even in the absence of spores.

Consider the practical implications of hyphal fragmentation in laboratory settings. Researchers often exploit this ability to culture fungi efficiently. For instance, a small piece of a fungal hypha, when placed in nutrient-rich media, can grow into a thriving colony within days. This technique is particularly useful for studying fungal genetics or producing biomass for industrial applications. To maximize success, ensure the media is sterile and contains essential nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, and minerals. Fragment sizes of 1–2 millimeters are ideal, as they balance viability and ease of handling.

From an ecological perspective, hyphal fragmentation plays a critical role in fungal dispersal and colonization. In natural environments, hyphae are constantly exposed to physical stresses—such as soil movement or predation—that can cause breakage. Rather than being a setback, this fragmentation allows fungi to spread rapidly across new substrates. For example, in forest ecosystems, fragmented hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi can colonize the roots of multiple plants, enhancing nutrient uptake and plant health. This process underscores the fungi’s ability to thrive in dynamic, resource-limited conditions.

However, hyphal fragmentation is not without limitations. Unlike spores, which are highly resistant to environmental stresses, fragmented hyphae are vulnerable to desiccation and pathogens. Their success depends on immediate access to moisture and nutrients, making them less suited for long-distance dispersal. Additionally, not all fungal species exhibit this ability equally; some, like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, are more adept at regenerating from fragments than others. Understanding these nuances is crucial for both scientific research and agricultural applications.

In conclusion, hyphal fragmentation exemplifies the versatility of fungal reproduction, offering a spore-independent pathway for growth and survival. Whether in the lab or the wild, this process highlights fungi’s ability to adapt and thrive under diverse conditions. By studying and harnessing this mechanism, we can unlock new possibilities in biotechnology, ecology, and beyond. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, mastering the art of hyphal fragmentation opens doors to deeper insights into the fascinating world of fungi.

Are All Bacillus Species Spore Formers? Unraveling the Microbial Mystery

You may want to see also

Parasexual Reproduction: Genetic recombination occurs without spores via hyphal fusion and nuclear exchange

Fungi are remarkably versatile in their reproductive strategies, and while spores are a common method, they are not the only route. Parasexual reproduction offers a fascinating alternative, allowing genetic recombination without the need for spore formation. This process hinges on the fusion of hyphae—the filamentous structures that make up fungal bodies—followed by the exchange and recombination of nuclei. Unlike sexual reproduction, which typically involves specialized structures like fruiting bodies and spores, parasexual reproduction occurs directly within the vegetative mycelium, making it a more streamlined yet equally effective means of genetic diversity.

Consider the steps involved in parasexual reproduction: First, hyphae from two compatible individuals fuse, forming a heterokaryotic cell containing nuclei from both parents. Next, these nuclei migrate and pair up, setting the stage for genetic exchange. During this phase, recombination occurs through mechanisms like crossing over or nuclear fusion, resulting in new genetic combinations. Finally, the recombined nuclei are distributed through the mycelium, allowing the fungus to express novel traits without ever producing a spore. This process is particularly advantageous in stable environments where rapid adaptation is less critical, as it bypasses the energy-intensive spore production and dispersal stages.

One practical example of parasexual reproduction is observed in *Aspergillus nidulans*, a fungus commonly studied in genetics. Researchers have manipulated this species to induce hyphal fusion and nuclear exchange under controlled conditions, demonstrating how environmental factors like nutrient availability and pH can influence the frequency of parasexual events. For instance, a study published in *Microbiology Spectrum* found that nitrogen limitation significantly increased hyphal fusion rates, suggesting that stress conditions may trigger this reproductive strategy. Such findings highlight the adaptability of fungi and provide insights into optimizing parasexual reproduction for biotechnological applications, such as strain improvement in industrial fungi.

While parasexual reproduction offers clear benefits, it is not without limitations. Unlike sexual reproduction, which ensures a complete shuffling of genetic material through meiosis, parasexual recombination is partial and less predictable. This can lead to uneven genetic outcomes, potentially limiting the diversity achievable through this method. Additionally, the reliance on hyphal compatibility restricts parasexual reproduction to closely related individuals, reducing its applicability in highly diverse fungal populations. Despite these drawbacks, the efficiency and simplicity of parasexual reproduction make it a valuable mechanism for fungi to maintain genetic plasticity in specific ecological contexts.

In conclusion, parasexual reproduction exemplifies the ingenuity of fungal life cycles, providing a spore-independent pathway for genetic recombination. By focusing on hyphal fusion and nuclear exchange, fungi can adapt and thrive in diverse environments without the complexities of spore-based reproduction. For researchers and practitioners, understanding this process opens doors to innovative applications, from enhancing fungal strains for biotechnology to studying evolutionary mechanisms in microbial systems. Whether in the lab or the wild, parasexual reproduction underscores the resilience and resourcefulness of fungi in the face of biological challenges.

Mastering Spore Modding: A Step-by-Step Guide to Custom Creations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, some fungi can reproduce without spores through asexual methods like fragmentation, budding, or vegetative propagation.

Examples include yeast (budding) and molds like Penicillium (fragmentation or hyphal growth).

No, while spores are common in sexual reproduction, some fungi use gametes or other structures like gametangia to reproduce sexually without spores.