Fungal spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by fungi to propagate and survive in diverse environments. These lightweight, resilient structures are dispersed through air, water, or animals, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats and endure harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. Spores play a crucial role in the fungal life cycle, serving as both a means of reproduction and a mechanism for long-term survival. They come in various shapes, sizes, and types, depending on the fungal species, and can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions trigger germination. Understanding fungal spores is essential for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as they contribute to processes ranging from nutrient cycling in ecosystems to causing plant and human diseases.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Fungal spores are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures produced by fungi for reproduction and dispersal. |

| Size | Typically range from 1 to 100 micrometers (μm) in diameter, depending on the fungal species. |

| Shape | Varied, including spherical, oval, cylindrical, or elongated, often with distinctive features like spines or appendages. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Primarily composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides, providing structural support and protection. |

| Reproduction Type | Can be asexual (e.g., conidia, spores produced by mitosis) or sexual (e.g., asci, basidiospores, produced by meiosis). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Dispersed via air, water, animals, or insects; some spores are actively ejected (ballistospores), while others are passively released. |

| Dormancy | Many spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh environmental conditions until favorable conditions return. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under suitable conditions (e.g., moisture, temperature, nutrients), developing into hyphae or other fungal structures. |

| Ecological Role | Essential for fungal survival, colonization of new habitats, and decomposition of organic matter in ecosystems. |

| Human Impact | Can cause allergies, respiratory issues (e.g., asthma), and infections (e.g., aspergillosis, candidiasis) in humans; also used in biotechnology and food production (e.g., mushrooms, yeast). |

| Examples | Conidia (e.g., Aspergillus), basidiospores (e.g., mushrooms), zygospores (e.g., Rhizopus), and ascospores (e.g., Saccharomyces). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Fungal Spores: Classification based on structure, function, and reproductive methods in fungi

- Sporulation Process: How fungi produce spores through asexual or sexual reproduction mechanisms

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Methods like wind, water, or animals that spread fungal spores widely

- Environmental Survival: Spores' ability to withstand harsh conditions like heat, cold, or dryness

- Health and Disease: Role of fungal spores in allergies, infections, and mycotoxin production

Types of Fungal Spores: Classification based on structure, function, and reproductive methods in fungi

Fungal spores are the microscopic units of reproduction in fungi, akin to seeds in plants. Their diversity is staggering, with each type adapted to specific environmental conditions and reproductive strategies. To understand this complexity, we classify fungal spores based on structure, function, and reproductive methods. This classification not only highlights their unique roles but also underscores their ecological significance.

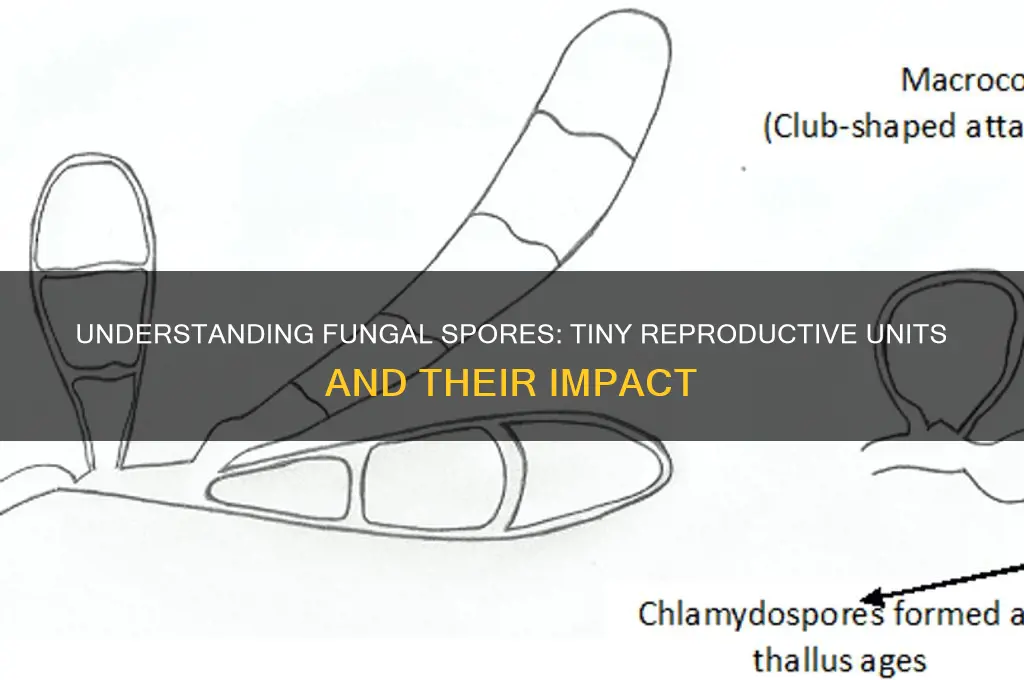

Structurally, fungal spores fall into distinct categories, each designed for survival and dispersal. Zygospores, for instance, are thick-walled and resilient, formed through the fusion of two haploid cells in zygomycetes. These spores are built to endure harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures or desiccation, making them ideal for long-term survival. In contrast, conidia are asexual spores produced at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae in molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. Their thin walls and lightweight structure allow for easy dispersal by wind or water, facilitating rapid colonization of new habitats. Ascospores and basidiospores, produced in sac-like structures (asci) and on club-shaped structures (basidia) respectively, are examples of sexual spores. These spores are often more genetically diverse, enhancing the fungus’s adaptability to changing environments.

Functionally, spores serve as both survival and dispersal agents, but their roles vary widely. Chlamydospores, for example, are thick-walled, resting spores produced by fungi like *Candida* and *Fusarium*. They act as survival structures, remaining dormant until conditions improve. Sporangiospores, produced inside sporangia in fungi like *Rhizopus*, are asexual spores that disperse en masse, often propelled by air currents. Teliospores, found in rust fungi, are long-lived structures that germinate to produce basidia, ensuring the continuation of the fungal life cycle. Each spore type is tailored to its environment, whether it’s surviving drought, colonizing new substrates, or maintaining genetic diversity.

Reproductive methods further differentiate fungal spores, reflecting the complexity of fungal life cycles. Asexual spores, such as conidia and sporangiospores, are produced through mitosis and are genetically identical to the parent fungus. This method allows for rapid proliferation in favorable conditions. Sexual spores, like ascospores and basidiospores, result from meiosis and genetic recombination, increasing genetic variability. For example, the mushroom’s cap is a basidiocarp, a structure that produces and disperses basidiospores. Parthenospores, formed without fertilization, blur the line between asexual and sexual reproduction, showcasing the versatility of fungal reproductive strategies.

Understanding these classifications is not just academic—it has practical implications. For instance, knowing that conidia are lightweight and wind-dispersed helps explain why mold allergies spike during certain seasons. Similarly, the resilience of zygospores explains why some fungi persist in soil for decades. For gardeners, recognizing chlamydospores in pathogens like *Fusarium* can inform strategies to prevent soil-borne diseases. In medicine, the distinction between asexual and sexual spores is crucial for treating fungal infections, as sexual spores often exhibit greater drug resistance. By grasping these classifications, we can better manage fungi in agriculture, medicine, and environmental conservation.

Mastering Spore: A Beginner's Guide to Evolving Your Creature

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: How fungi produce spores through asexual or sexual reproduction mechanisms

Fungal spores are the microscopic units of reproduction, akin to seeds in plants, but their creation is a far more intricate process. The sporulation process is a fascinating mechanism through which fungi ensure their survival and proliferation, employing both asexual and sexual reproduction strategies. This process is not just a biological curiosity; it has significant implications for agriculture, medicine, and ecology, as fungal spores can be both beneficial and detrimental depending on the context.

Asexual Sporulation: A Rapid Multiplication Strategy

Asexual sporulation is the fungi’s go-to method for quick and efficient reproduction, especially in stable environments. This process involves the production of spores such as conidia, sporangiospores, or chlamydospores, which are genetically identical to the parent fungus. For instance, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* genera produce conidia on specialized structures called conidiophores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air or water, allowing the fungus to colonize new territories rapidly. A key advantage of asexual sporulation is its speed; under optimal conditions, a single fungal colony can produce millions of spores within days. However, this method lacks genetic diversity, making the offspring vulnerable to environmental changes or antifungal agents. To mitigate this, some fungi produce thick-walled chlamydospores, which can survive harsh conditions like drought or extreme temperatures, acting as a fungal "insurance policy."

Sexual Sporulation: The Genetic Shuffle

In contrast, sexual sporulation is a more complex and energy-intensive process, reserved for stressful conditions or when genetic diversity is crucial. This mechanism involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals, resulting in a diploid zygote. The zygote then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, such as asci in Ascomycetes or basidiospores in Basidiomycetes. For example, mushrooms (Basidiomycetes) release basidiospores from gills or pores, which are carried by wind to new locations. Sexual sporulation is slower and less frequent than asexual methods, but it generates genetic recombination, enabling fungi to adapt to changing environments or resist diseases. This diversity is why sexually produced spores are often more resilient and better equipped for long-term survival.

Practical Implications and Control Measures

Understanding the sporulation process is critical for managing fungal populations, particularly in agriculture and healthcare. For instance, farmers combating powdery mildew (caused by *Erysiphe* spp.) can disrupt asexual sporulation by reducing humidity or applying fungicides like sulfur or strobilurins. In medical settings, controlling fungal spores is essential to prevent infections, especially in immunocompromised patients. HEPA filters and antifungal agents like fluconazole target spore production and dispersal. Interestingly, some fungi, like *Trichoderma*, are used as biocontrol agents to outcompete pathogenic fungi by disrupting their sporulation process.

Comparative Analysis: Asexual vs. Sexual Sporulation

While asexual sporulation prioritizes speed and quantity, sexual sporulation emphasizes quality and adaptability. Asexual spores dominate in stable, resource-rich environments, whereas sexual spores thrive in unpredictable or stressful conditions. This duality ensures fungal survival across diverse ecosystems. For example, *Fusarium* spp. rely heavily on asexual spores for rapid spread in crops, but they also produce sexual spores to survive winter. By studying these mechanisms, researchers can develop targeted strategies to either promote beneficial fungi (e.g., mycorrhizal species) or suppress harmful ones (e.g., *Candida* spp.).

Takeaway: Harnessing the Sporulation Process

The sporulation process is a testament to fungi’s adaptability and resilience. By understanding the nuances of asexual and sexual reproduction, we can better manage fungal populations in various contexts. Whether it’s optimizing mushroom cultivation, preventing crop diseases, or treating fungal infections, the key lies in disrupting or enhancing sporulation at the right stage. For instance, home gardeners can reduce fungal pathogens by improving air circulation and avoiding overhead watering, which minimizes conditions conducive to asexual sporulation. In contrast, mycologists can induce sexual sporulation in lab settings by manipulating light, temperature, and nutrient availability. This knowledge transforms the sporulation process from a biological phenomenon into a practical tool for human benefit.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Spores Successfully

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Methods like wind, water, or animals that spread fungal spores widely

Fungal spores are nature’s microscopic hitchhikers, relying on external forces to travel far and wide. Among these forces, wind stands as the most prolific dispersal mechanism. Lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or tails, spores from species such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* can be carried for miles, even crossing continents. This aerial journey ensures fungi colonize new habitats, from forest floors to indoor environments, where they play roles in decomposition, food production, and even human health. For instance, a single cubic meter of air can contain up to 10,000 fungal spores, highlighting wind’s efficiency in spore dispersal.

Water, though less universal than wind, serves as a vital dispersal agent for aquatic and semi-aquatic fungi. Species like *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, the chytrid fungus responsible for amphibian declines, rely on water currents to spread. Spores released into streams, ponds, or rainwater can travel downstream, infecting new populations of amphibians. Similarly, splash from raindrops can eject spores from soil or plant surfaces, propelling them into the air or nearby water bodies. Gardeners and conservationists should note: managing water flow in habitats can limit the spread of harmful fungi, protecting vulnerable species.

Animals, both large and small, act as unwitting couriers for fungal spores. Mammals, birds, and insects can carry spores on their fur, feathers, or exoskeletons, transporting them across ecosystems. For example, bats in caves spread *Histoplasma capsulatum* spores in their guano, posing risks to humans who disturb these areas. Similarly, insects like flies and beetles may feed on fungal fruiting bodies, dispersing spores as they move. Even humans contribute, tracking spores on shoes or clothing into new environments. To minimize this, outdoor enthusiasts should clean gear after visiting fungal-rich areas, reducing accidental spore transfer.

Comparing these mechanisms reveals their synergy in fungal survival. Wind offers range, water provides precision in specific habitats, and animals ensure targeted delivery to nutrient-rich areas. Each method complements the others, maximizing fungi’s ability to colonize diverse environments. For instance, a spore carried by wind might land on an animal, which then transports it to a water source, where it can infect a new host. Understanding these interactions is crucial for managing fungal diseases, whether in agriculture, forestry, or human health. By disrupting one or more dispersal pathways, we can mitigate the spread of harmful fungi while preserving their beneficial roles in ecosystems.

Mastering Fern Propagation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Ferns from Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$92.62 $150

Environmental Survival: Spores' ability to withstand harsh conditions like heat, cold, or dryness

Fungal spores are nature's ultimate survivalists, engineered to endure environments that would destroy most life forms. Their resilience to extreme heat, cold, and desiccation is not just a passive trait but an active strategy honed over millennia. For instance, spores of the fungus *Aspergillus* can survive temperatures exceeding 60°C (140°F), a feat achieved through a robust cell wall composed of chitin and melanin, which acts as a thermal shield. This adaptability ensures their persistence in diverse ecosystems, from scorching deserts to frozen tundra.

Consider the practical implications of this survival mechanism. In food preservation, understanding spore resistance is critical. Canning processes, for example, require temperatures of 121°C (250°F) under pressure to eliminate bacterial spores, but fungal spores like those of *Byssochlamys* can still survive in improperly processed jams or acidic foods. Home canners must follow precise guidelines—such as processing high-acid foods for 10–20 minutes and low-acid foods for 20–100 minutes—to ensure safety. Ignoring these protocols risks contamination, as spores can germinate when conditions become favorable, leading to spoilage or even foodborne illness.

From a comparative perspective, fungal spores outshine many other microorganisms in their ability to withstand dryness. While bacterial spores require moisture to germinate, fungal spores can remain dormant in arid conditions for years, even decades. The desert fungus *Eurotium* thrives in environments with less than 10% humidity, its spores protected by a thick, impermeable wall that minimizes water loss. This contrasts sharply with plant seeds, which often require specific moisture levels to break dormancy. Such resilience makes fungal spores ideal candidates for astrobiology studies, as their survival strategies could inform the search for life on Mars, where extreme dryness and temperature fluctuations prevail.

To harness this resilience in agriculture, farmers can adopt spore-based biofungicides like *Trichoderma*, which colonize plant roots and protect against pathogens even in harsh climates. These beneficial fungi survive soil temperatures ranging from -10°C to 50°C (14°F to 122°F), making them effective in both temperate and tropical regions. Application rates typically range from 100–500 grams per hectare, depending on crop type and soil conditions. However, overuse can lead to resistance, so rotating biofungicides with chemical treatments is advisable. This dual approach maximizes crop protection while minimizing environmental impact.

In conclusion, the environmental survival of fungal spores is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Whether in food safety, astrobiology, or agriculture, their ability to withstand heat, cold, and dryness offers both challenges and opportunities. By studying these mechanisms, we can develop strategies to combat spoilage, explore extraterrestrial life, and enhance sustainable farming practices. The key lies in respecting their resilience while leveraging it for human benefit.

Understanding Spore Formation: A Survival Mechanism in Microorganisms

You may want to see also

Health and Disease: Role of fungal spores in allergies, infections, and mycotoxin production

Fungal spores are microscopic, lightweight structures produced by fungi to disperse and survive in various environments. While many are harmless, certain spores play a significant role in human health, triggering allergies, causing infections, and producing mycotoxins that can lead to severe illness. Understanding their impact is crucial for prevention and treatment.

Allergies: Invisible Triggers in the Air

Inhaling fungal spores, particularly from molds like *Cladosporium*, *Aspergillus*, and *Alternaria*, can provoke allergic reactions in susceptible individuals. Symptoms range from sneezing and itchy eyes to asthma exacerbations. For example, *Alternaria* spores are a common culprit in seasonal allergies, with peak levels often coinciding with late summer and early fall. To minimize exposure, keep indoor humidity below 50%, use air purifiers with HEPA filters, and regularly clean areas prone to mold growth, such as bathrooms and basements. For severe cases, allergists may recommend immunotherapy or prescribe antihistamines like loratadine (10 mg daily for adults) to manage symptoms.

Infections: Opportunistic Pathogens in Action

Fungal spores can cause infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS, undergoing chemotherapy, or on long-term corticosteroids. *Aspergillus* spores, for instance, can lead to aspergillosis, a condition ranging from allergic reactions to severe lung infections. *Candida* spores, commonly found in the human microbiome, can overgrow and cause candidiasis, especially in the mouth (thrush) or genital area. Prevention strategies include maintaining good hygiene, avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use, and monitoring indoor environments for mold. Treatment often involves antifungal medications like fluconazole (150–300 mg daily for adults) for candidiasis or voriconazole for aspergillosis, tailored to the infection’s severity.

Mycotoxin Production: Silent Poison in the Environment

Certain fungi, such as *Aspergillus*, *Penicillium*, and *Fusarium*, produce mycotoxins—toxic compounds that contaminate food and indoor environments. Aflatoxins, produced by *Aspergillus flavus*, are among the most dangerous, linked to liver cancer and acute poisoning. Exposure can occur through contaminated grains, nuts, or even moldy buildings. To reduce risk, inspect food for mold before consumption, store grains in dry conditions, and address water damage in homes promptly. In cases of suspected mycotoxin exposure, medical evaluation may include liver function tests and, in severe cases, treatment with activated charcoal to bind toxins in the gut.

Practical Takeaways for Everyday Protection

While fungal spores are ubiquitous, their health impacts can be mitigated with proactive measures. For allergies, monitor local spore counts and limit outdoor activities during high-risk periods. For infections, strengthen immunity through a balanced diet and regular exercise. To avoid mycotoxins, prioritize food safety and maintain mold-free living spaces. By understanding the specific roles of fungal spores in health and disease, individuals can take targeted steps to protect themselves and their families.

Understanding Mold Spores Lifespan: How Long Do They Survive?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungal spores are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures produced by fungi for reproduction and dispersal. They are analogous to seeds in plants and serve as a means for fungi to spread and colonize new environments.

Fungal spores form through various reproductive processes, such as asexual (e.g., conidia, spores produced by budding or fragmentation) or sexual (e.g., asci or basidiospores, formed after fungal mating) methods. These processes occur in specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia.

Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment, found in soil, air, water, and on surfaces. They thrive in damp, warm, and organic-rich environments, such as decaying plant matter, but can also be present indoors in moldy areas.

Most fungal spores are harmless, but some can cause allergies, respiratory issues (e.g., asthma), or infections in individuals with weakened immune systems. Pathogenic fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Candida* can lead to serious health problems if inhaled or ingested.

Fungal spores can be controlled by reducing moisture levels, improving ventilation, and cleaning mold-prone areas. Using dehumidifiers, fixing leaks, and avoiding organic debris buildup can also help. In severe cases, professional mold remediation may be necessary.