The intricate world of mushrooms and their networks, known as mycorrhizal networks, is a fascinating one. These networks, discovered by Suzanne Simard in 1997, are formed by the intertwining of fungal filaments called hyphae with tree roots, creating a complex underground ecosystem. This symbiotic relationship allows trees to communicate and share resources, such as water, nutrients, and sugars, while the fungi benefit from a steady supply of sugar. The largest organism in the world is a honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains, spanning almost four square miles. German forester Peter Wohlleben coined the term Wood Wide Web to describe this hidden network, which connects and supports life in our forests and beyond.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Mycorrhizal network (also known as a common mycorrhizal network or CMN) |

| Discovery | Discovered in 1997 by Suzanne Simard, professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia in Canada |

| Description | An underground network found in forests and other plant communities, created by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi joining with plant roots |

| Function | Connects individual plants, allowing them to transfer water, nitrogen, carbon, and other minerals, as well as infochemicals related to attacks by pathogens or herbivores |

| Intelligence | Exhibits primitive intelligence with decision-making ability and memory |

| Size | Can vary from microscopic to colossal sizes; the world's largest organism is a honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains, covering more than 2,300 acres |

| Benefits | Facilitates mutualistic relationships, with both plants and fungi benefiting from shared resources and protection |

| Conservation | The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) aims to map and protect these networks to mitigate climate change and preserve biodiversity |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycorrhizal networks, or common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs), are formed by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi joining with plant roots

- These networks can connect many different plants and facilitate the transfer of infochemicals, allowing plants to react to attacks by pathogens or herbivores

- Mycorrhizal relationships can be mutualistic, commensal, or parasitic, and can change between these types of symbiosis over time

- The formation and nature of these networks are context-dependent and influenced by factors such as soil fertility, resource availability, and host genotype

- The world's largest mycelial network is a honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains, covering more than 2,300 acres

Mycorrhizal networks, or common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs), are formed by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi joining with plant roots

Mycorrhizal networks, or common mycorrhizal networks (CMNs), are intricate underground networks that form when the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi join with plant roots. These networks are prevalent in forests and other plant communities, creating connections between individual plants. The relationship between the fungi and plants in a mycorrhizal network is often mutualistic, with both organisms benefiting from the association. However, it is important to note that the nature of these relationships can vary, ranging from mutualism to commensalism or parasitism, and a single partnership may shift between these different types of symbiosis over time.

The formation and characteristics of mycorrhizal networks are influenced by various factors, including soil fertility, resource availability, and the genotype of the host or mycosymbiont. These networks play a crucial role in the transfer of infochemicals, allowing plants to communicate and respond to attacks by pathogens or herbivores. Through the network, plants can manifest physical and biochemical changes, such as strengthening their cell walls or producing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to defend against pathogens.

Mycorrhizal networks also facilitate the transfer of water, nitrogen, carbon, and other essential minerals between connected plants. This sharing of resources is vital for the survival of saplings in shady areas, as they receive nutrients and sugar from older trees through the network. Hub trees, also known as "mother trees," play a central role in these networks. They are usually the oldest and most seasoned trees in a forest, with the most fungal connections. Their established root systems enable them to access deeper sources of water and nutrients, which they distribute to younger trees.

The discovery of mycorrhizal networks is attributed to Suzanne Simard, a professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia. Simard's field studies revealed the existence of underground networks of fungi connecting trees, resembling neural networks in the brain. German forester Peter Wohlleben coined the term "Wood Wide Web" to describe these intricate networks, highlighting their role in enabling trees to communicate and share resources.

Mycorrhizal networks have profound implications for our understanding of evolution and symbiosis. They have sparked inquiries into the possibility that symbiosis, rather than competition, may be the primary driver of evolution. Additionally, the study of these networks has led to initiatives like the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN), which aims to map and protect these complex ecosystems to mitigate climate change and preserve Earth's biodiversity.

Mushroom Magic: Grannies' Secrets to Success

You may want to see also

These networks can connect many different plants and facilitate the transfer of infochemicals, allowing plants to react to attacks by pathogens or herbivores

Mycorrhizal networks, also known as common mycorrhizal networks (CMN), are underground networks of fungi that connect with plant roots. They are formed by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi intertwining with the roots of plants. These networks can connect many different plants and facilitate the transfer of infochemicals, allowing plants to react to attacks by pathogens or herbivores.

Infochemicals are signals that plants can use to communicate with each other. When a plant is attacked by a pathogen or herbivore, it can release infochemicals that warn other plants of the threat. The mycorrhizal network allows these infochemicals to travel quickly between plants, so they can respond to the danger. This is possible because the network protects the infochemicals from hazards such as leaching and degradation, which are risks associated with transmission through the soil.

The transfer of infochemicals between plants through mycorrhizal networks has been observed in several studies. For example, studies have reported concentrations of allelochemicals two to four times higher in plants connected by mycorrhizal networks. This suggests that the networks increase the transfer rate of these chemicals and expand the range of their dispersal, known as the bioactive zone.

Mycorrhizal networks provide a shared pathway for plants to transfer infochemicals and other substances, such as water, nitrogen, carbon, and other minerals. This allows plants to support each other, particularly in challenging environments. For instance, saplings in shady areas with limited sunlight can receive nutrients and sugar from older trees through the mycorrhizal network, increasing their chances of survival.

Additionally, mycorrhizal networks can facilitate tree cooperation, with older trees nurturing younger seedlings. Hub trees, also known as "mother trees," have the most fungal connections and play a crucial role in detecting and supporting the health of their neighboring trees. These complex symbiotic relationships between trees and fungi have profound implications for species survival and our understanding of evolution.

Mushroom Hunting in Connecticut: Best Seasons

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal relationships can be mutualistic, commensal, or parasitic, and can change between these types of symbiosis over time

Mycorrhizal networks, also known as common mycorrhizal networks (CMN), are underground networks found in forests and other plant communities. These networks are formed by the hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi joining with plant roots, connecting individual plants together. Mycorrhizal relationships are most commonly mutualistic, but they can also be commensal or parasitic, and they can change between these types of symbiosis over time.

In a mutualistic mycorrhizal relationship, both the plant and the fungus benefit. The plant makes organic molecules through photosynthesis and provides them to the fungus in the form of sugars or lipids. In return, the fungus supplies the plant with water and mineral nutrients, such as phosphorus, taken from the soil. This type of relationship is particularly beneficial for plants in nutrient-poor soils. Additionally, the mycorrhizal network can facilitate the transfer of infochemicals, allowing plants to communicate and respond to attacks by pathogens or herbivores.

However, in certain species or circumstances, mycorrhizal relationships can be parasitic. For example, some orchids are entirely mycoheterotrophic, lacking chlorophyll for photosynthesis, and derive their carbon entirely from the fungus partner. In this case, the plant benefits more from the relationship, making it a non-mutualistic, parasitic type of symbiosis.

The formation and nature of mycorrhizal networks are context-dependent and influenced by factors such as soil fertility, resource availability, and host genetics. For example, some plant species benefit from mycorrhizal relationships in conditions of low soil fertility but are harmed in higher soil fertility. Additionally, both plants and fungi can form symbiotic relationships with multiple partners and can preferentially allocate resources to one partner over another.

Mycorrhizal networks have profound implications for the growth, fitness, and diversity of both plants and fungi, as well as for soil structure, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem sustainability. They have even been hypothesized to possess a primitive form of intelligence, with decision-making abilities and memory. German forester Peter Wohlleben dubbed this network the "wood wide web," emphasizing the complex communication and connections that occur through the mycelium.

How Do Oyster Mushrooms Smell?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The formation and nature of these networks are context-dependent and influenced by factors such as soil fertility, resource availability, and host genotype

The formation and nature of mycorrhizal networks are influenced by various factors, including soil fertility, resource availability, and host genotype. Mycorrhizal networks, discovered by forest ecologist Suzanne Simard in 1997, are underground networks of fungi that connect plants and trees, resembling neural networks in the brain. These networks facilitate the transfer of water, nitrogen, carbon, and other minerals, allowing plants to share resources and communicate.

Soil fertility plays a crucial role in the formation and nature of mycorrhizal networks. Some plant species, such as buckhorn plantain, thrive in mycorrhizal relationships under low soil fertility conditions but are negatively impacted when soil fertility is higher. This context-dependent nature of the networks highlights the adaptability of plants and fungi in associating with multiple symbiotic partners.

Resource availability is another key factor influencing mycorrhizal networks. Fungi in these networks can sense the presence of resources and distribute them efficiently across the network. For example, in shady areas, saplings may not have enough sunlight for adequate photosynthesis. Mycorrhizal networks enable older, taller trees to send nutrients and sugar to these saplings, ensuring their survival.

Host genotype also influences the formation and nature of mycorrhizal networks. Experiments have revealed the heritability of mycorrhizal colonization, indicating that plants and fungi have evolved genetic traits that influence their interactions. These interactions can be mutualistic, commensal, or parasitic, and they can shift between these types of symbiosis over time.

Disturbance and seasonal variation are additional factors that can impact the formation and nature of mycorrhizal networks. For example, the presence of pathogens or herbivores can trigger physical and biochemical changes in plants, leading to the production of defensive enzymes. These changes can then be communicated through the mycorrhizal network, allowing nearby plants to respond and prepare accordingly.

Understanding the context-dependent nature of mycorrhizal networks and the factors influencing their formation is crucial for comprehending the complex relationships between plants, fungi, and their environment. These networks play a vital role in the evolution of plant life and the overall health and connectivity of ecosystems.

Fresh Mushrooms: Sawdust Secrets for Success

You may want to see also

The world's largest mycelial network is a honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains, covering more than 2,300 acres

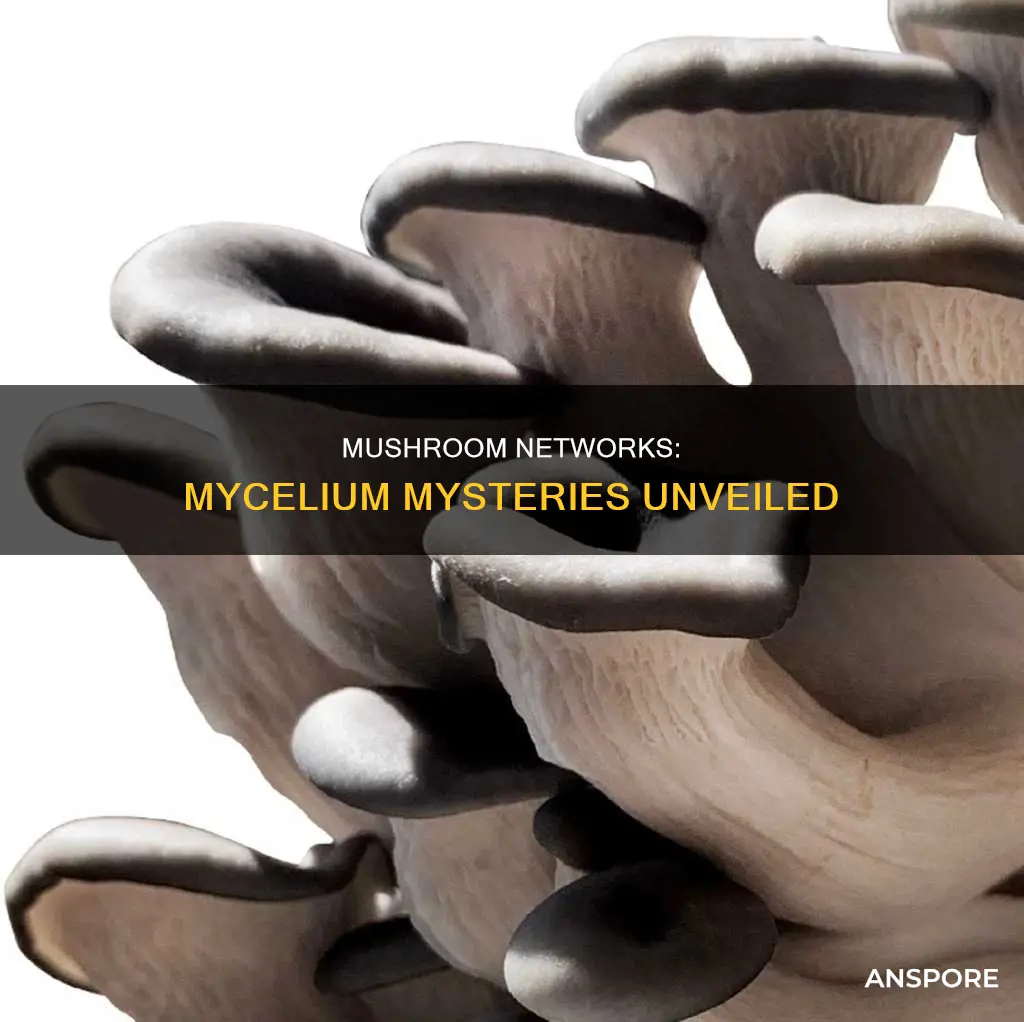

Mycelial networks, often referred to as "mushroom networks," are intricate root-like structures that connect mushrooms together, facilitating nutrient and information exchange. These networks are formed by filamentous hyphae, which grow and branch out, connecting to other hyphae and creating a complex web-like system. In nature, mycelial networks play a crucial role in the decomposition of organic matter, nutrient cycling, and even communication between plants and fungi.

Now, let's talk about the world's largest known mycelial network: a honey mushroom (Armillaria ostoyae) network in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon. This extraordinary fungal network spans more than 2,300 acres (930 hectares), making it the largest single organism ever discovered by area. The vast network was first discovered in the 1990s, and further research and mapping have helped scientists understand its incredible extent and longevity.

The honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains is believed to be ancient, with estimates placing its age at around 2,400 years old. Its longevity is attributed to the ability of mycelial networks to continuously grow and expand, forming new connections and merging with other networks. This particular network has thrived in the ideal conditions provided by the mountain ecosystem, where it has accessed a plentiful supply of wood debris and other organic matter to feed upon.

The scale and interconnectedness of this honey mushroom network are remarkable. It is estimated that the total length of the hyphae in this network could exceed thousands of miles, if not more. This vast network allows the honey mushrooms to colonize and decompose large areas of forest, playing a crucial role in the ecosystem by breaking down dead wood and recycling nutrients back into the soil.

The discovery and study of this massive mycelial network have provided valuable insights into the complex and fascinating world of fungi. It highlights the importance of mycorrhizal relationships between plants and fungi, where both parties benefit from exchanging nutrients and protecting against pathogens. Additionally, the study of this network has contributed to a better understanding of fungal genetics, ecology, and the potential for using fungi in various applications, from medicine to environmental remediation.

The honey mushroom network in Oregon's Blue Mountains stands as a testament to the incredible adaptability and resilience of fungal networks. It serves as a reminder that there is still much to learn and discover about the intricate and often invisible world of mycelial networks, and the essential roles they play in our ecosystems.

Mushroom Supplements: Do They Work?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom networks are called mycorrhizal networks.

Mycorrhizal networks are underground networks of fungi that connect with plant roots. They are also referred to as CMN (common mycorrhizal networks).

Mycorrhizal networks allow plants to communicate and share resources such as water, nitrogen, carbon, and other minerals. They also enable plants to transfer infochemicals related to attacks by pathogens or herbivores, allowing receiving plants to react in the same way.

Mycorrhizal networks are made of mycelium, which are thin fungal strands called hyphae that wrap around or bore into tree roots.

Mycorrhizal networks can be found in forests and other plant communities. They are widespread, with estimates suggesting that the total length of mycorrhizal fungi in the top 10 centimeters of soil is more than 450 quadrillion kilometers.