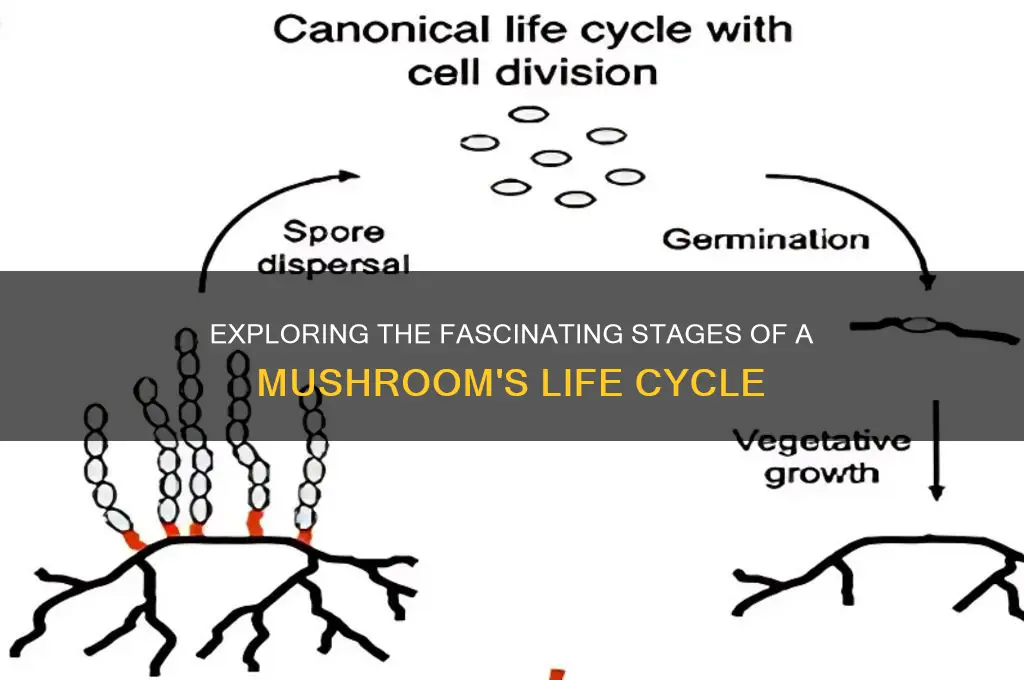

Mushrooms, often misunderstood as simple organisms, undergo a fascinating and complex life cycle that is crucial to their survival and reproduction. The stages of a mushroom's life begin with sporulation, where mature mushrooms release microscopic spores into the environment. These spores, akin to plant seeds, are dispersed by wind, water, or animals and germinate under favorable conditions to form hyphae, thread-like structures that grow and intertwine to create a network called mycelium. The mycelium, often hidden beneath the soil or within organic matter, is the mushroom's primary vegetative stage, responsible for nutrient absorption. When conditions are right—typically involving adequate moisture, temperature, and food—the mycelium develops into a primordia, the embryonic stage of the mushroom. Finally, the primordia matures into the fruiting body, the visible part of the mushroom we commonly recognize, which then releases spores to begin the cycle anew. This intricate process highlights the mushroom's adaptability and its vital role in ecosystems as decomposers and nutrient recyclers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Germination | A single spore lands on a suitable substrate and germinates, forming a haploid cell. |

| Hyphal Growth | The germinated spore grows into a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, forming the mycelium. |

| Mycelium Development | The mycelium expands, absorbing nutrients from the substrate and growing vegetatively. |

| Karmas Formation | Under favorable conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity), the mycelium aggregates to form a primordium, the embryonic stage of the mushroom. |

| Fruiting Body Development | The primordium grows into a mature mushroom, consisting of a cap (pileus), stem (stipe), and gills or pores. |

| Sporulation | The gills or pores produce and release spores, typically through wind or water dispersal. |

| Senescence | The mushroom ages, collapses, or decomposes, returning nutrients to the substrate. |

| Dormancy (Optional) | In some species, the mycelium may enter a dormant state during unfavorable conditions, reactivating when conditions improve. |

| Reproduction Types | Mushrooms can reproduce both sexually (via spore fusion) and asexually (via mycelial fragmentation). |

| Substrate Dependency | Mushrooms rely on organic matter (e.g., wood, soil) as a substrate for growth and nutrient absorption. |

| Environmental Triggers | Fruiting is often triggered by changes in temperature, humidity, light, or substrate availability. |

| Lifespan | The fruiting body is short-lived (days to weeks), while the mycelium can persist for years or decades. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Germination: Spores land, absorb water, and germinate, initiating the mushroom's life cycle

- Mycelium Growth: Thread-like mycelium spreads, absorbing nutrients and forming the mushroom's vegetative body

- Primordia Formation: Tiny pin-like structures (primordia) emerge as the mushroom begins to develop

- Fruiting Body Growth: The mushroom cap and stem grow rapidly, reaching maturity for spore release

- Spore Release: Gills or pores release spores, completing the cycle and ensuring reproduction

Spore Germination: Spores land, absorb water, and germinate, initiating the mushroom's life cycle

The life cycle of a mushroom begins with spore germination, a critical phase where the foundation for the entire organism is established. Spores, which are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units, are released into the environment by mature mushrooms. These spores are lightweight and can be carried by air currents, water, or animals to new locations. Once a spore lands on a suitable substrate—such as soil, wood, or decaying organic matter—it enters the first stage of its life cycle. The success of this stage depends on the spore finding an environment with adequate moisture, nutrients, and oxygen, as these factors are essential for its survival and growth.

Upon landing, the spore absorbs water from its surroundings, a process known as hydration. This water intake causes the spore to swell and break its protective outer wall, activating its metabolic processes. Hydration is crucial because it reawakens the dormant spore, enabling it to transition from a state of inactivity to one of active growth. Without sufficient water, the spore remains dormant and cannot proceed to the next stage of its life cycle. This step highlights the spore's remarkable ability to remain viable for extended periods until conditions are favorable for germination.

Once hydrated, the spore begins to germinate, marking the initiation of the mushroom's life cycle. During germination, the spore's nucleus divides, and a small, thread-like structure called a hypha emerges. This hypha is the building block of the mushroom's vegetative body, known as the mycelium. The hypha grows and branches out, forming a network that spreads through the substrate in search of nutrients. This network is essential for the mushroom's survival, as it allows the organism to absorb water, organic matter, and minerals from its environment. The germination process is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, requiring a balance of temperature, humidity, and pH to proceed successfully.

As the hypha continues to grow and branch, it develops into a mycelium, which is the primary growth form of the fungus. The mycelium is a complex, multicellular structure that can cover large areas, often remaining hidden beneath the surface of the substrate. It plays a vital role in nutrient cycling and decomposition in ecosystems. During this phase, the mycelium stores energy and resources, preparing for the eventual formation of the mushroom's fruiting body. The transition from spore to mycelium is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of fungi, as they thrive in diverse environments and conditions.

In summary, spore germination is the pivotal stage where a dormant spore transforms into an active, growing organism. Through hydration, the spore awakens and initiates metabolic activity, leading to the emergence of a hypha. This hypha expands into a mycelium, laying the groundwork for the mushroom's development. This stage underscores the importance of environmental factors in fungal reproduction and growth, setting the stage for the subsequent phases of the mushroom's life cycle. Without successful germination, the spore's genetic potential remains unrealized, and the cycle cannot continue.

Mushroom Kingdom Shop: Power Moons Collection

You may want to see also

Mycelium Growth: Thread-like mycelium spreads, absorbing nutrients and forming the mushroom's vegetative body

The mycelium growth stage is a critical and fascinating phase in the life cycle of a mushroom, marking the beginning of its development. This stage is characterized by the proliferation of thread-like structures called mycelium, which serve as the mushroom's vegetative body. Mycelium consists of a network of fine, branching hyphae that spread through the substrate, such as soil, wood, or other organic matter. These hyphae are incredibly efficient at absorbing nutrients, water, and minerals from their environment, which are essential for the mushroom's growth and survival. As the mycelium expands, it forms a dense, interconnected web that can cover large areas, often remaining hidden beneath the surface.

During mycelium growth, the primary focus of the mushroom is to establish a robust and extensive network to maximize nutrient uptake. The hyphae secrete enzymes that break down complex organic materials into simpler compounds, which are then absorbed and utilized for energy and growth. This process is not only vital for the mushroom but also plays a significant role in ecosystem health, as mycelium helps decompose organic matter and recycle nutrients back into the environment. The ability of mycelium to adapt to various substrates and conditions highlights its resilience and importance in fungal biology.

As the mycelium spreads, it forms a mat-like structure known as the mycelial fan or colony. This colony acts as the foundation for future mushroom development, storing energy and resources that will be used during the reproductive stages. The growth rate and extent of the mycelium depend on factors such as temperature, humidity, substrate quality, and available nutrients. Optimal conditions promote rapid and healthy mycelium expansion, while suboptimal conditions may slow or hinder growth. Understanding these requirements is crucial for cultivators and researchers aiming to support mycelium development.

The mycelium also serves as a protective and communicative network for the mushroom. It can detect and respond to environmental changes, such as the presence of competitors or pathogens, by altering its growth patterns or producing defensive compounds. Additionally, mycelium can connect different plants and fungi through a phenomenon known as the "wood wide web," facilitating the exchange of nutrients and information. This interconnectedness underscores the mycelium's role not just as a nutrient absorber but as a vital component of ecological relationships.

In summary, mycelium growth is a foundational stage in the mushroom's life cycle, where thread-like mycelium spreads, absorbs nutrients, and forms the vegetative body. This stage is marked by the efficient breakdown and uptake of organic materials, the formation of extensive mycelial networks, and the establishment of a resource base for future development. By understanding and supporting mycelium growth, we gain insights into the remarkable biology of mushrooms and their contributions to ecosystems. This stage is not only essential for the mushroom's survival but also highlights the intricate and dynamic nature of fungal life.

Goomba Mushroom: Friend or Foe?

You may want to see also

Primordia Formation: Tiny pin-like structures (primordia) emerge as the mushroom begins to develop

Primordia formation marks a critical transition in the mushroom's life cycle, signaling the shift from mycelial growth to the development of visible fruiting bodies. This stage begins when the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, senses optimal environmental conditions such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability. In response, the mycelium aggregates and initiates the differentiation of cells that will form the primordia. These tiny, pin-like structures are the embryonic forms of what will eventually become the mushroom. Primordia formation is a highly regulated process, driven by genetic and environmental cues, ensuring that the fungus allocates resources efficiently to produce fruiting bodies when conditions are favorable.

The emergence of primordia is a delicate and intricate process, often occurring just beneath the substrate surface or on the mycelium itself. These structures are initially microscopic but rapidly grow into visible pins, typically ranging from 1 to 5 millimeters in height. Their appearance resembles small bumps or knots, and they are often white or light-colored, depending on the mushroom species. The primordia are composed of densely packed hyphae (fungal threads) that begin to organize into the distinct parts of the mushroom, such as the stipe (stem) and pileus (cap). This stage is crucial because it lays the foundation for the mushroom's morphology and determines its potential for further growth.

Environmental factors play a pivotal role in primordia formation. Adequate humidity is essential, as dry conditions can halt or reverse the process. Temperature also influences the rate of primordia development, with most species requiring specific ranges to trigger this stage. Light exposure, though not always necessary, can stimulate primordia formation in some mushrooms, particularly those that fruit above ground. Additionally, the substrate must provide sufficient nutrients to support the energy-intensive process of primordia development. Without these optimal conditions, the mycelium may delay or abort the formation of primordia, conserving resources until the environment becomes more favorable.

From a biological perspective, primordia formation involves complex cellular and molecular changes. The mycelium undergoes a process called dedifferentiation, where specialized cells revert to a more generalized state, allowing them to reorganize into the structures of the mushroom. Hormone-like compounds, such as gibberellins and auxins, are believed to play a role in regulating this process, though the exact mechanisms vary among species. As the primordia grow, they begin to differentiate into the various tissues of the mushroom, including the hymenium (spore-bearing surface) and the supportive structures of the cap and stem. This stage is a testament to the fungus's ability to adapt and respond to its environment with precision.

For cultivators and enthusiasts, recognizing primordia formation is essential for managing mushroom growth. In controlled environments, such as grow rooms or laboratories, maintaining stable conditions during this stage is critical to ensure successful fruiting. Observing the emergence of primordia also provides valuable feedback on the health and vitality of the mycelium. By understanding and supporting this stage, growers can optimize yields and produce high-quality mushrooms. Primordia formation, though often overlooked, is a fascinating and fundamental step in the mushroom's life cycle, bridging the gap between invisible mycelial networks and the iconic fruiting bodies we recognize.

Freeze-Drying Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide to Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Fruiting Body Growth: The mushroom cap and stem grow rapidly, reaching maturity for spore release

The fruiting body growth stage is a critical and visually striking phase in the life cycle of a mushroom. After the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, has colonized its substrate and accumulated sufficient nutrients, it begins to initiate the development of the fruiting body. This structure, which includes the cap and stem, is specifically designed for spore production and dispersal. The process is triggered by environmental cues such as changes in temperature, humidity, and light, which signal to the mycelium that conditions are favorable for reproduction. Once these signals are detected, the mycelium redirects its energy toward rapidly constructing the fruiting body, marking the beginning of this dynamic growth phase.

During fruiting body growth, the mushroom cap and stem emerge and expand at an astonishing rate. The cap, or pileus, starts as a small, rounded structure and quickly unfolds to its mature shape, which can vary widely among species—from convex to flat or even umbrella-like. Simultaneously, the stem, or stipe, elongates to support the cap and elevate it above the substrate, ensuring optimal spore dispersal. This rapid growth is fueled by the nutrients stored in the mycelium and the continuous absorption of water and minerals from the environment. The cells in the fruiting body divide and expand, driven by enzymes and turgor pressure, resulting in a structure that can sometimes grow several centimeters in a single day.

As the fruiting body matures, it undergoes subtle but crucial changes in preparation for spore release. The cap’s underside, known as the hymenium, develops structures like gills, pores, or teeth, depending on the mushroom species. These structures house the basidia, the specialized cells where spores are produced. The spores themselves are formed through a process of meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity. Concurrently, the cap and stem reach their full size and color, often becoming more vibrant or changing hue as they mature. This maturation process is tightly regulated to ensure that spore release occurs at the optimal time for successful dispersal.

The culmination of fruiting body growth is the release of spores, the primary means of fungal reproduction. Once the mushroom has fully matured, the spores are discharged from the basidia, often in response to environmental triggers like air currents or raindrops. In some species, the spores are actively ejected through a mechanism called ballistospore discharge, while in others, they are passively released. The cap and stem play a vital role in this process by positioning the spore-bearing structures in a way that maximizes dispersal. After spore release, the fruiting body begins to senesce, as its primary function has been fulfilled, and the mushroom’s life cycle transitions back to the mycelial stage, awaiting the next opportunity to fruit.

Understanding fruiting body growth is essential for both mycologists and cultivators, as it highlights the intricate balance between environmental conditions and fungal development. By manipulating factors like humidity, light, and substrate composition, growers can optimize this stage to produce healthy, spore-rich mushrooms. For enthusiasts and foragers, recognizing the signs of a mature fruiting body—such as fully developed gills or pores and a stable cap shape—ensures the collection of mushrooms at their peak. This stage not only showcases the mushroom’s remarkable ability to grow rapidly but also underscores its role as a reproductive organ, vital for the continuation of fungal species.

Mushroom Fruiting: Best Times and Practices

You may want to see also

Spore Release: Gills or pores release spores, completing the cycle and ensuring reproduction

The spore release stage is a critical phase in the life cycle of a mushroom, marking the culmination of its reproductive process. Once the mushroom has matured, its gills or pores—depending on the species—become the primary structures for spore dispersal. Gills are thin, blade-like structures found on the underside of the cap in many mushrooms, while pores are small openings present in species like boletes. These structures house the spores, which are microscopic reproductive units analogous to seeds in plants. When the mushroom reaches full maturity, the spores are ready to be released into the environment, ensuring the continuation of the species.

The release of spores is a highly efficient and passive process, driven by environmental factors such as air currents, rain, or even the movement of nearby animals. In gill-bearing mushrooms, the spores are typically located on the surface of the gills. As the mushroom dries slightly, the spores are ejected into the air, often in a cloud-like manner, due to the drying and shrinking of the gill tissue. This mechanism maximizes the distance spores can travel, increasing the likelihood of finding a suitable substrate for germination. In pore-bearing mushrooms, spores are released more gradually as they accumulate in the pores and are dislodged by external forces like wind or water.

Environmental conditions play a significant role in the timing and success of spore release. Optimal humidity and temperature are essential for the gills or pores to function effectively. If conditions are too dry, the spores may not be released efficiently; if too wet, they may clump together and fail to disperse. Mushrooms have evolved to release spores during periods when environmental conditions favor their survival and germination, such as in the early morning when moisture levels are high but not excessive.

Once released, spores are carried away by air or water currents, eventually landing on a substrate like soil, wood, or decaying matter. For germination to occur, the substrate must provide the necessary nutrients and conditions, such as moisture and appropriate temperature. If a spore lands in a suitable environment, it will develop into a hypha, a thread-like structure that grows and branches out to form a network called mycelium. This mycelium will then continue the life cycle by absorbing nutrients and, under the right conditions, producing new mushrooms.

Spore release is not only a mechanism for reproduction but also a strategy for survival and colonization. A single mushroom can release millions of spores, vastly increasing the chances of successful germination and establishment in new habitats. This prolific dispersal ensures that mushrooms can thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forests to grasslands, and even in urban environments. By completing the life cycle through spore release, mushrooms contribute to the decomposition of organic matter, nutrient cycling, and the overall health of their ecosystems, making this stage indispensable to their existence.

Mellow Mushroom Birthday Perks: What's on Offer?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main stages of a mushroom's life cycle are spore germination, mycelium growth, primordium formation, fruiting body development, and spore release.

Mushrooms reproduce by releasing spores, which are dispersed through air, water, or animals. These spores germinate under suitable conditions to start a new life cycle.

Mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus, consisting of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. It absorbs nutrients, grows, and eventually forms the mushroom's fruiting body.

The fruiting body is the visible part of the mushroom, such as the cap and stem. It forms to produce and release spores, ensuring the continuation of the species.

The duration of each stage varies by species and environmental conditions. Spore germination can take days to weeks, mycelium growth months to years, and fruiting body development days to weeks.