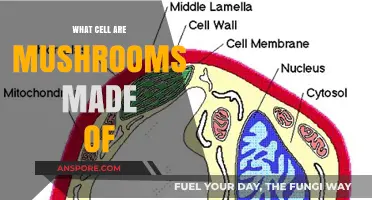

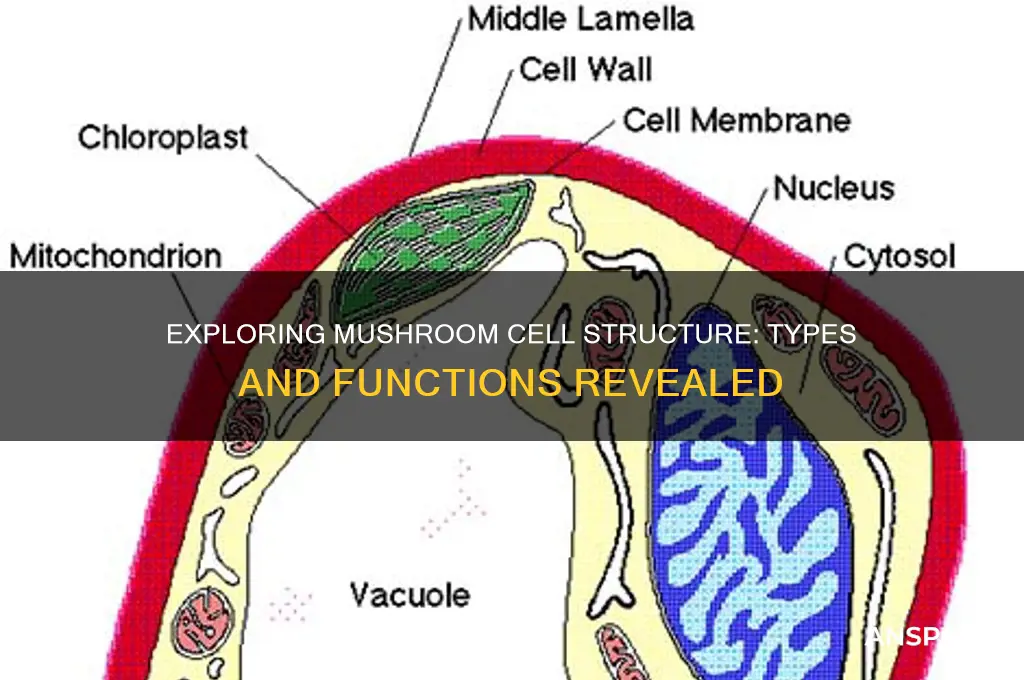

Mushrooms, as fungi, possess a unique cellular structure distinct from plants and animals. Unlike plant cells, which have rigid cell walls made of cellulose, mushroom cells feature walls composed primarily of chitin, a tough, flexible polysaccharide also found in insect exoskeletons. These cells are typically elongated and thread-like, forming a network called hyphae, which collectively make up the mushroom's body, or mycelium. Within these cells, mushrooms contain organelles like nuclei, mitochondria, and vacuoles, but lack chloroplasts, as they do not perform photosynthesis. Instead, mushrooms obtain nutrients by absorbing organic matter from their environment, making their cellular structure highly adapted to their saprotrophic or symbiotic lifestyles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cell Type | Eukaryotic |

| Cell Wall | Present (composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides) |

| Nucleus | Present (membrane-bound, contains genetic material) |

| Organelles | Standard eukaryotic organelles (e.g., mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus) |

| Chloroplasts | Absent (mushrooms are heterotrophic and do not perform photosynthesis) |

| Vacuoles | Present (large central vacuoles for storage and structural support) |

| Septa | Present in some species (pores in cell walls allowing cytoplasmic continuity between cells) |

| Hyphal Structure | Multicellular fungi with filamentous hyphae composed of elongated cells |

| Cell Division | Mitosis and meiosis (for vegetative growth and sexual reproduction, respectively) |

| Cell Size | Variable (hyphal cells can be elongated, often 10-100 μm in diameter) |

| Cell Shape | Elongated and tubular in hyphae, spherical or irregular in spores |

| Cell Specialization | Differentiated cells for specific functions (e.g., spores, fruiting bodies) |

| Cell Communication | Via septal pores and plasmodesmata-like structures for nutrient and signal exchange |

| Cell Longevity | Variable (some cells short-lived, others persist in mycelium networks) |

Explore related products

$11.99

What You'll Learn

- Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms consist of thread-like cells called hyphae, forming a network called mycelium

- Cell Walls: Mushroom cells have rigid walls made of chitin, unlike plant cell walls

- Nuclei: Hyphal cells contain multiple nuclei, allowing for efficient nutrient distribution

- Vacuoles: Large central vacuoles store water, nutrients, and waste in mushroom cells

- Spores: Specialized cells called spores are produced for reproduction and dispersal

Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms consist of thread-like cells called hyphae, forming a network called mycelium

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are composed of unique cellular structures that set them apart from plants and animals. At the heart of a mushroom’s anatomy is the hyphal structure, which is fundamental to its growth, nutrient absorption, and overall function. Mushrooms consist of thread-like cells called hyphae, which are long, slender, and tubular in shape. These hyphae are the building blocks of the fungus and are responsible for its ability to explore and interact with its environment. Each hypha is typically divided into compartments by cross-walls called septa, which contain pores allowing for the flow of nutrients, cytoplasm, and organelles between cells. This interconnected system enables efficient resource distribution throughout the fungal organism.

Hyphae collectively form a vast, branching network known as the mycelium, which serves as the mushroom’s primary body. The mycelium is often hidden beneath the surface of the substrate (such as soil or decaying wood) and can span large areas, sometimes covering acres. This network is highly adaptive, allowing the fungus to efficiently absorb water, minerals, and organic compounds from its surroundings. The mycelium is also the site of vegetative growth, where the fungus expands and colonizes new areas. It is through this extensive hyphal network that mushrooms can decompose organic matter, recycle nutrients, and form symbiotic relationships with plants, such as in mycorrhizal associations.

The structure of hyphae is optimized for their function. Each hypha is surrounded by a rigid cell wall composed primarily of chitin, a tough polysaccharide that provides structural support and protection. Unlike plant cells, hyphae lack chlorophyll and cannot photosynthesize, so they rely on absorbing nutrients from external sources. The tips of hyphae are particularly active, growing and branching as they explore their environment in search of food. This growth is driven by the internal pressure of the cytoplasm and the secretion of enzymes that break down complex organic materials into simpler forms that can be absorbed.

The hyphal network is not just a passive structure but a dynamic system that responds to environmental cues. For example, when conditions are favorable, the mycelium may allocate resources to form fruiting bodies—the visible mushrooms we see above ground. These structures are produced to disperse spores, ensuring the survival and propagation of the fungus. The transition from mycelial growth to mushroom formation is a complex process regulated by factors such as nutrient availability, humidity, and temperature, all of which are sensed and responded to by the hyphal network.

In summary, the hyphal structure is the cornerstone of a mushroom’s existence, with thread-like hyphae forming the mycelium that sustains the organism. This network is essential for nutrient absorption, growth, and reproduction, showcasing the remarkable adaptability and efficiency of fungal biology. Understanding the hyphal structure provides key insights into how mushrooms function and thrive in diverse ecosystems, highlighting their importance in nutrient cycling and ecological balance.

Sauteed Mushrooms: How to Achieve Caramelization

You may want to see also

Cell Walls: Mushroom cells have rigid walls made of chitin, unlike plant cell walls

Mushroom cells possess a distinctive feature that sets them apart from plant cells: their cell walls are composed primarily of chitin, a tough, polysaccharide material. This structural component is fundamentally different from the cellulose-based cell walls found in plants. Chitin provides mushrooms with the necessary rigidity and support, enabling them to maintain their shape and withstand environmental pressures. Unlike cellulose, chitin is also found in the exoskeletons of arthropods, highlighting its unique role in the fungal kingdom. This difference in cell wall composition is a key factor in distinguishing fungi from plants, both taxonomically and functionally.

The chitin-based cell walls of mushrooms serve multiple purposes beyond structural support. Chitin is highly resistant to degradation, which contributes to the durability of fungal tissues. This resistance allows mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying organic matter. Additionally, chitin plays a role in protecting the cell from mechanical stress and pathogens. Its rigid nature ensures that mushroom cells can maintain their integrity even in challenging conditions, such as fluctuating moisture levels or physical disturbances. This adaptability is a testament to the evolutionary advantages of chitin in fungal cell walls.

In contrast to plant cell walls, which are primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, mushroom cell walls lack these plant-specific components. The absence of cellulose in fungi is a critical distinction, as it underscores the separate evolutionary paths of plants and fungi. While both groups have cell walls, their compositions reflect their unique biological needs and ecological roles. For instance, cellulose in plants aids in water retention and structural flexibility, whereas chitin in mushrooms prioritizes rigidity and resistance to degradation. This difference highlights the specialized nature of fungal cell walls in supporting the fungal lifestyle.

The rigid nature of chitin-based cell walls is particularly important for mushrooms, as it enables them to grow upright and form complex structures like fruiting bodies. This rigidity is essential for the mushroom's ability to disperse spores effectively, a critical aspect of its reproductive cycle. In comparison, plant cell walls, while providing structure, are more flexible due to the presence of cellulose and other components. This flexibility allows plants to grow in diverse shapes and sizes but differs from the rigid, chitin-based framework that defines fungal morphology.

Understanding the composition of mushroom cell walls also has practical implications, especially in fields like biotechnology and materials science. Chitin is being explored for its potential applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry due to its biocompatibility and strength. For example, chitin-based materials are being developed for wound healing, drug delivery, and biodegradable packaging. By studying mushroom cell walls, scientists can unlock new possibilities for sustainable and innovative solutions inspired by nature. This highlights the significance of chitin not only in fungal biology but also in its broader applications.

In summary, the cell walls of mushrooms, composed of chitin, are a defining feature that distinguishes them from plant cells. This rigid structure provides essential support, protection, and durability, enabling mushrooms to thrive in various environments. The contrast with cellulose-based plant cell walls underscores the unique evolutionary adaptations of fungi. Beyond their biological role, chitin-based cell walls offer valuable insights and opportunities for technological advancements, making the study of mushroom cells a fascinating and impactful area of research.

Are Grocery Store Mushrooms Grown in Manure? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Nuclei: Hyphal cells contain multiple nuclei, allowing for efficient nutrient distribution

Mushrooms, like other fungi, are composed of a network of filamentous structures called hyphae, which collectively form the mycelium. The fundamental units of this structure are hyphal cells, and one of their most distinctive features is the presence of multiple nuclei within each cell. This multinucleate condition, known as coenocytic organization, is a key adaptation that supports the unique biology of fungi. Unlike plant and animal cells, which typically contain a single nucleus, hyphal cells can house numerous nuclei, a trait that significantly enhances their functionality, particularly in nutrient distribution.

The multiple nuclei in hyphal cells play a crucial role in the efficient distribution of nutrients throughout the fungal network. As the mycelium grows and explores its environment, it absorbs nutrients from organic matter in the soil or substrate. These nutrients must then be transported across the extensive hyphal network to support growth, reproduction, and other metabolic activities. The presence of multiple nuclei allows for localized control of nutrient utilization and distribution, ensuring that resources are allocated where they are most needed. This decentralized system enables rapid responses to environmental changes and optimizes the fungus’s ability to thrive in diverse conditions.

Another advantage of multiple nuclei in hyphal cells is their contribution to genetic diversity and adaptability. During the fungal life cycle, nuclei can divide independently of cell division, a process known as syncytial growth. This allows for genetic recombination and mutation within a single hyphal cell, increasing the potential for variation. When nutrients are distributed, this genetic diversity can influence how different parts of the mycelium respond to their environment, enhancing the fungus’s resilience and ability to colonize new habitats. The multinucleate nature of hyphal cells thus serves as a mechanism for both efficient resource management and evolutionary flexibility.

Furthermore, the multiple nuclei in hyphal cells facilitate the coordination of complex cellular processes. For instance, during the formation of fruiting bodies (such as mushrooms), specific regions of the mycelium undergo differentiation to produce spores. The nuclei in these regions can specialize in directing the synthesis of proteins, enzymes, and other molecules required for development. This specialization ensures that nutrient distribution is finely tuned to support the energy-intensive process of spore production. Without the presence of multiple nuclei, such coordinated and localized activities would be far less efficient.

In summary, the multiple nuclei within hyphal cells are a critical feature of fungal biology, particularly in the context of nutrient distribution. This multinucleate organization enables efficient resource allocation, genetic diversity, and the coordination of complex cellular processes. By allowing for localized control and rapid adaptation, the nuclei in hyphal cells ensure that mushrooms and other fungi can effectively utilize their environment and thrive in a wide range of ecological niches. Understanding this unique cellular structure provides valuable insights into the remarkable efficiency and adaptability of fungal organisms.

Popcorn Mushrooms: Hulless Wonder

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Vacuoles: Large central vacuoles store water, nutrients, and waste in mushroom cells

Mushrooms, like other fungi, possess unique cellular structures that differentiate them from plants and animals. One of the most striking features of mushroom cells is the presence of large central vacuoles. These vacuoles are essential organelles that serve multiple critical functions within the cell. Primarily, they act as storage compartments, holding water, nutrients, and waste products. This storage capability is vital for mushrooms, as it allows them to maintain turgor pressure, which is crucial for their structural integrity, especially in the absence of a rigid cell wall like that found in plants.

The large central vacuoles in mushroom cells are dynamic structures that can expand or contract based on the cell's needs. When water is abundant, the vacuole swells, helping the mushroom maintain its shape and firmness. Conversely, during periods of water scarcity, the vacuole shrinks, conserving resources and preventing cellular damage. This adaptability is key to the mushroom's survival in diverse environments, from damp forest floors to drier habitats. Additionally, the vacuole's ability to store nutrients ensures that the mushroom has a readily available energy reserve, supporting growth and metabolic processes.

Another critical function of the large central vacuoles is waste management. As mushrooms metabolize nutrients and grow, they produce waste products that need to be sequestered to prevent toxicity within the cell. The vacuole acts as a detoxification center, isolating harmful byproducts and maintaining cellular health. This waste storage capability is particularly important in mushrooms, as they often grow in nutrient-rich but potentially toxic environments, such as decaying organic matter. By efficiently managing waste, the vacuole contributes to the overall resilience and longevity of the mushroom.

Furthermore, the large central vacuoles play a role in osmoregulation, the process by which cells maintain the correct balance of water and solutes. In mushrooms, this is essential for adapting to varying environmental conditions. For instance, when the external environment becomes hypertonic (high in solutes), the vacuole can release water to prevent the cell from shrinking. Conversely, in a hypotonic environment (low in solutes), the vacuole can absorb excess water to avoid cell bursting. This osmoregulatory function is facilitated by the vacuole's semi-permeable membrane, which allows selective movement of substances in and out of the organelle.

In summary, the large central vacuoles in mushroom cells are multifunctional organelles that are indispensable for the organism's survival and growth. They store water, nutrients, and waste, manage turgor pressure, and regulate osmotic balance, all of which are critical for the mushroom's ability to thrive in its environment. Understanding the role of these vacuoles provides valuable insights into the unique cellular biology of fungi and highlights their adaptability as a kingdom of organisms. By studying these structures, scientists can gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate mechanisms that enable mushrooms to flourish in diverse ecological niches.

Select Mushrooms: Freshness and Quality Guide

You may want to see also

Spores: Specialized cells called spores are produced for reproduction and dispersal

Mushrooms, like other fungi, have unique cellular structures that differ from plants and animals. Among these specialized cells, spores play a critical role in the reproduction and dispersal of mushrooms. Spores are microscopic, single-celled structures produced by fungi to ensure their survival and propagation. Unlike seeds in plants, spores are haploid cells, meaning they contain half the genetic material of the parent organism. This characteristic allows them to develop into new fungal individuals under favorable conditions.

Spores are produced in specialized structures within the mushroom, such as the gills, pores, or teeth, depending on the species. For example, in agaric mushrooms, spores are formed on the gills located beneath the cap. Each spore is a self-contained unit capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures, ensuring the fungus can survive in diverse habitats. Once mature, spores are released into the environment, often in vast numbers, to increase the likelihood of successful dispersal and colonization.

The process of spore dispersal is highly efficient and adapted to the mushroom's ecological niche. Many mushrooms rely on wind to carry spores over long distances, a mechanism known as sporulation. Some species have evolved mechanisms to actively eject spores, such as the "ballistospore" method used by certain basidiomycetes, where spores are launched into the air with explosive force. Others may depend on water, animals, or insects for dispersal, ensuring spores reach new substrates where they can germinate and grow.

Upon landing in a suitable environment, a spore germinates by absorbing water and nutrients, initiating the growth of a hypha, a thread-like structure that forms the basis of the fungal network called the mycelium. This mycelium then expands, colonizing the substrate and eventually producing new mushrooms under the right conditions. This cycle highlights the spore's dual role as both a reproductive unit and a survival mechanism, enabling fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

In summary, spores are indispensable specialized cells in mushrooms, designed for reproduction and dispersal. Their resilience, combined with efficient dispersal mechanisms, ensures the continuity and spread of fungal species. Understanding spores provides valuable insights into the unique biology of mushrooms and their ecological significance in nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics.

Mushrooms: Nature's Emotional Healers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms, like other fungi, have eukaryotic cells, which contain a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles.

Yes, mushrooms have specialized cells such as hyphae, which are filamentous structures that form the mycelium, and basidia, which produce spores for reproduction.

Yes, mushroom cells have cell walls, but unlike plants, their cell walls are primarily composed of chitin, a polysaccharide found in arthropod exoskeletons.

No, mushroom cells do not have chloroplasts. Unlike plants, fungi like mushrooms are heterotrophs and obtain nutrients by absorbing organic matter from their environment.