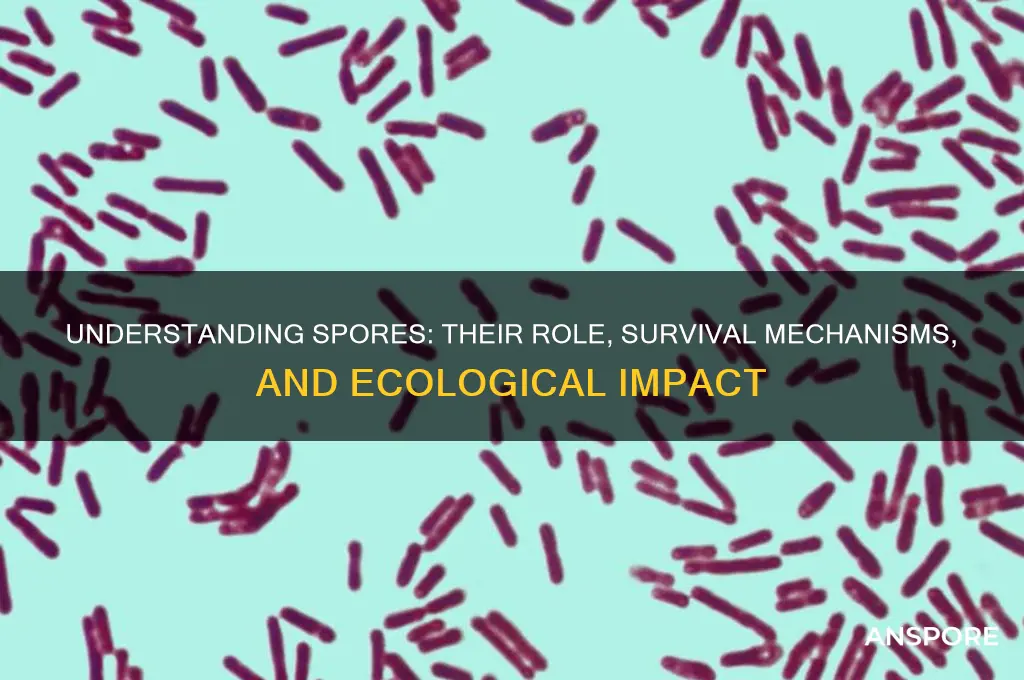

Spores are microscopic, dormant structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, as a means of survival and reproduction. Acting as resilient, protective capsules, spores enable organisms to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, drought, or lack of nutrients. When conditions become favorable, spores germinate, giving rise to new individuals or structures, ensuring the continuation of the species. In plants like ferns and mosses, spores develop into gametophytes, which produce reproductive cells, while in fungi, they grow into hyphae, forming the basis of new fungal colonies. This adaptive strategy allows spores to disperse widely, colonize new habitats, and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival Mechanism | Spores are highly resistant structures that allow organisms to survive harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, sometimes for centuries, until favorable conditions for growth return. |

| Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures (e.g., wings, flagella) that aid in dispersal by wind, water, or animals, enabling colonization of new habitats. |

| Reproduction | Spores serve as reproductive units in many organisms, such as fungi, plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some bacteria (e.g., endospores). |

| Genetic Diversity | Spores can undergo genetic recombination during formation, increasing genetic diversity and adaptability in offspring. |

| Resistance to UV Radiation | Spores have thick, protective walls that shield their genetic material from harmful UV radiation. |

| Metabolic Inactivity | Spores are metabolically inactive, reducing energy requirements and increasing longevity in adverse conditions. |

| Germination | Under suitable conditions, spores can germinate, resuming metabolic activity and developing into new individuals. |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a crucial role in ecosystems by facilitating the survival and spread of species across diverse environments. |

| Size | Spores are typically microscopic, ranging from 1 to 50 micrometers in diameter, depending on the species. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Survival Mechanism: Spores withstand harsh conditions like heat, cold, and drought, ensuring species survival

- Reproduction: Spores are reproductive units that disperse to grow into new organisms

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new environments for colonization

- Dormancy: Spores remain inactive until favorable conditions trigger germination and growth

- Genetic Diversity: Spores facilitate genetic variation through mutation and recombination during dispersal

Survival Mechanism: Spores withstand harsh conditions like heat, cold, and drought, ensuring species survival

Spores are nature's ultimate survival capsules, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Unlike seeds, which require immediate access to water and nutrients to germinate, spores can remain dormant for decades, even centuries, waiting for the perfect moment to revive. This resilience is not just a passive trait but an active strategy. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C, radiation exposure, and desiccation by shutting down metabolic activity and encasing themselves in a protective protein coat. Such adaptability ensures that even if the parent organism perishes, the species persists.

Consider the practical implications of this survival mechanism in agriculture. Farmers in drought-prone regions could benefit from spore-based technologies, such as mycorrhizal fungi spores, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots to enhance water absorption. A single gram of soil can contain thousands of fungal spores, each capable of colonizing crops and improving their resilience to arid conditions. To implement this, mix 10–20 grams of spore-rich mycorrhizal inoculant per plant during sowing, ensuring the spores are evenly distributed in the root zone. This method has been shown to increase crop yields by up to 30% in water-scarce environments.

From an evolutionary standpoint, spores represent a masterclass in efficiency. Take tardigrades, microscopic animals that produce egg-like spores when faced with extreme conditions. These "water bears" can survive the vacuum of space, radiation levels 1,000 times higher than the human lethal dose, and temperatures ranging from -272°C to 150°C. Their spores achieve this by replacing intracellular water with a protective sugar called trehalose, which prevents cellular damage. While tardigrades are an extreme example, their spore mechanism underscores the principle that survival often hinges on minimizing vulnerability during hostile periods.

For home gardeners, understanding spore behavior can revolutionize plant care. Ferns, for instance, reproduce via spores that require specific conditions to germinate—a process called sporulation. To cultivate ferns from spores, start by collecting mature spore cases (indusia) from the underside of fern fronds. Sprinkle these spores onto a sterile, moist growing medium kept at a constant 20–25°C. Patience is key, as fern spores can take 2–3 months to develop into prothalli, the preliminary stage before the fern emerges. This method not only saves costs but also preserves rare fern species threatened by habitat loss.

Finally, the industrial sector is harnessing spore technology for preservation and sustainability. In food production, Bacillus subtilis spores are used as probiotics to extend shelf life and enhance nutrient absorption. These spores withstand pasteurization temperatures (72°C for 15 seconds) and remain viable in harsh gastrointestinal conditions, delivering benefits to the host. Similarly, in wastewater treatment, spore-forming bacteria degrade pollutants under anaerobic conditions, where other microbes fail. By leveraging spore resilience, industries can reduce waste and improve efficiency, proving that nature’s survival mechanisms have applications far beyond the wild.

Understanding Spores: Biology's Tiny Survival Masters Explained Simply

You may want to see also

Reproduction: Spores are reproductive units that disperse to grow into new organisms

Spores are nature's ingenious solution to survival and propagation, especially in challenging environments. These microscopic units serve as the reproductive backbone for various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria. Unlike seeds, which are encased in protective structures, spores are lightweight and resilient, designed for dispersal over vast distances. This adaptability allows them to colonize new habitats, ensuring the continuity of their species even in adverse conditions.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of spore-driven reproduction. Ferns produce spores on the undersides of their fronds, which are released into the wind. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment—moist and shaded—it germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte. This intermediate stage then produces male and female reproductive cells, which combine to form a new fern plant. This process highlights the spore's dual role: a vehicle for dispersal and a self-contained unit capable of initiating new life.

For gardeners and horticulturists, understanding spore reproduction is crucial for cultivating spore-bearing plants like ferns and mosses. To propagate ferns, collect spores by placing a mature frond on paper until the spores drop. Sow these spores on a sterile, moist growing medium, such as a mix of peat and perlite, and keep them in a humid environment with indirect light. Patience is key, as spore germination can take several weeks. For mosses, blend collected moss with buttermilk or yogurt to create a slurry, then spread it on soil or stone surfaces. This method mimics natural spore dispersal and encourages growth in desired areas.

Comparatively, fungal spores operate on a different scale but with similar efficiency. Mushrooms release billions of spores into the air, each capable of growing into a new fungus if it lands in a nutrient-rich environment. This mass dispersal strategy ensures that at least some spores find favorable conditions, even in unpredictable ecosystems. For instance, mushroom spores can survive extreme temperatures and dryness, only activating when moisture and food sources are available. This resilience underscores the spore's role as a survival mechanism, not just a reproductive tool.

In practical terms, spores' dispersal mechanisms have inspired technological innovations. Scientists have developed spore-like microcapsules for drug delivery, leveraging their durability and targeted release capabilities. Similarly, agricultural researchers study spore dispersal to improve crop pollination and pest control strategies. By mimicking nature's design, we can enhance efficiency in fields ranging from medicine to agriculture. Whether in the wild or the lab, spores exemplify the power of simplicity in solving complex problems.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Spores Successfully

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new environments for colonization

Spores are nature's survival capsules, designed to endure harsh conditions and travel vast distances in search of new habitats. Their dispersal methods—wind, water, and animals—are not random but finely tuned strategies that ensure the continuation of species across diverse environments. Each method exploits the unique characteristics of the medium, maximizing the chances of successful colonization.

Wind dispersal is perhaps the most widespread and efficient method, particularly for lightweight spores. Fungi like puffballs and ferns release spores that are carried aloft by the slightest breeze, sometimes traveling miles before settling. For instance, a single mushroom can release up to 16 billion spores in a day, a staggering number that ensures at least a few will find fertile ground. To optimize wind dispersal, spores are often equipped with wings, tails, or lightweight structures that increase their airborne time. Gardeners and farmers can inadvertently aid this process by avoiding excessive tilling or disturbance of soil, which can release dormant spores into the air.

Water dispersal is another critical method, especially for spores in aquatic or humid environments. Algae, certain fungi, and plants like mosses release spores that float on water currents, colonizing new areas downstream or along coastlines. For example, the spores of *Azolla*, a water fern, can survive in freshwater ecosystems and are often transported during floods. This method is particularly effective in tropical regions with heavy rainfall. To harness water dispersal, conservationists can create spore banks from endangered aquatic species, reintroducing them into restored habitats via controlled water flow.

Animal dispersal is a more targeted approach, relying on creatures to carry spores to specific locations. Spores may attach to an animal's fur, feathers, or even digestive tract, as seen in the case of bird-dispersed seeds. For instance, the spores of certain slime molds can adhere to insects, which then transport them to nutrient-rich areas. Farmers and ecologists can encourage this by maintaining wildlife corridors or introducing spore-carrying species into degraded ecosystems. A practical tip: planting spore-producing plants near animal trails can increase the likelihood of dispersal.

Each dispersal method highlights the adaptability of spores, showcasing their role as pioneers in ecological succession. While wind and water cast a wide net, animal dispersal ensures precision, often targeting nutrient-rich areas like animal droppings or decaying matter. Understanding these mechanisms allows us to mimic nature's strategies in conservation efforts, such as reintroducing spore-rich materials into barren landscapes. By studying these methods, we gain insights into how life persists and thrives, even in the most challenging environments.

Discovering Reliable Sources for Mushroom Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dormancy: Spores remain inactive until favorable conditions trigger germination and growth

Spores are nature's time capsules, designed to endure harsh conditions that would destroy most life forms. This survival strategy hinges on dormancy, a state of suspended animation where metabolic activity is minimized. During dormancy, spores can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, remaining viable for years, decades, or even centuries. This remarkable resilience allows them to persist in environments where active growth would be impossible, from the arid deserts to the deep ocean trenches.

Consider the desert fungus *Aspergillus niger*, whose spores can lie dormant in the soil for extended periods. When rain finally arrives, the spores detect the increased moisture and temperature, triggering germination. Within hours, they sprout hyphae, the filamentous structures that absorb nutrients and begin the fungal life cycle anew. This process is not random; spores are equipped with sensory mechanisms that detect specific environmental cues, such as humidity levels, nutrient availability, and light exposure. For instance, some spores require a minimum of 70% relative humidity and a temperature range of 25–30°C to initiate germination.

The dormancy of spores is not merely a passive waiting game but an active, energy-efficient strategy. During this phase, spores reduce their metabolic rate to as little as 1% of their active state, conserving resources while remaining poised for revival. This efficiency is critical for survival in unpredictable environments, where favorable conditions may arise infrequently. For example, spores of the bacterium *Bacillus anthracis* can remain dormant in soil for decades, only to germinate when ingested by a grazing animal, causing anthrax. Understanding this mechanism has practical implications, such as in food preservation, where controlling humidity and temperature can prevent spore germination and extend shelf life.

Comparatively, the dormancy of plant seeds and animal embryos shares similarities with spore dormancy but differs in key ways. While seeds often require specific chemical signals (e.g., gibberellins) or physical treatments (e.g., scarification) to break dormancy, spores typically rely on environmental factors alone. This distinction highlights the adaptability of spores, which must thrive in more diverse and extreme conditions. For instance, spores of the fern *Ceratopteris richardii* can germinate within 24 hours of exposure to water, a process that is both rapid and highly responsive to environmental cues.

In practical terms, harnessing spore dormancy has applications in agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. Farmers can use spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis* as biofertilizers, applying them to soil where they remain dormant until conditions favor plant growth. In medicine, understanding spore dormancy helps combat infections caused by spore-forming pathogens, such as *Clostridium difficile*, by targeting the germination process. For hobbyists, creating a spore germination experiment at home is simple: place a spore-contaminated surface (e.g., moldy bread) in a sealed container with a damp paper towel, maintain a temperature of 25°C, and observe germination within 24–48 hours. This hands-on approach underscores the accessibility and relevance of spore biology in everyday life.

Does Vinegar Effectively Kill Mold Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Genetic Diversity: Spores facilitate genetic variation through mutation and recombination during dispersal

Spores, those microscopic, resilient units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are not just survival capsules—they are engines of genetic diversity. Unlike seeds, which often rely on sexual reproduction, spores frequently undergo asexual reproduction, yet they still manage to introduce genetic variation through mutation and recombination during dispersal. This process is critical for species survival, enabling populations to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern. When a fern releases spores, these tiny units are carried by wind or water to new locations. During this journey, exposure to environmental stressors like UV radiation or temperature fluctuations can induce mutations in the spore’s DNA. These mutations, though rare, introduce new genetic traits into the population. For instance, a spore might develop a mutation that enhances its tolerance to drought, a trait that could become vital in aridifying climates. Such genetic shifts, while small, accumulate over generations, fostering resilience.

Recombination, another mechanism driving genetic diversity, occurs when spores from different sources land in close proximity and fuse during germination. This process, common in fungi like mushrooms, allows for the exchange of genetic material between individuals. For example, in a forest floor teeming with fungal spores, the fusion of spores from two genetically distinct parents can produce offspring with novel combinations of traits. This genetic shuffling is akin to a natural breeding program, ensuring that fungal populations remain adaptable to threats like pathogens or habitat changes.

Practical applications of spore-driven genetic diversity are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers cultivating crops like wheat or rice, which have evolved from spore-producing ancestors, benefit from the genetic variability introduced by spores. This diversity allows breeders to select strains resistant to pests or tolerant of extreme weather. Similarly, in biotechnology, scientists harness spore-derived genetic variation to engineer microorganisms for tasks like bioremediation or drug production. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis*, a spore-forming bacterium, is used in soil cleanup due to its ability to degrade pollutants, a capability enhanced by its genetic adaptability.

To maximize the benefits of spore-driven genetic diversity, consider these steps: first, preserve natural habitats where spore-producing organisms thrive, as these environments foster genetic exchange. Second, in controlled settings like labs or greenhouses, expose spores to mild stressors (e.g., low doses of UV light or varying temperatures) to encourage mutation without compromising viability. Finally, monitor populations over time to track the emergence of beneficial traits, ensuring that genetic diversity translates into tangible advantages. By understanding and leveraging these processes, we can harness spores’ role as catalysts for evolution, securing the health and sustainability of ecosystems and industries alike.

Effective Temperatures to Eliminate Mold Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore is a reproductive structure produced by certain organisms, such as fungi, bacteria, and plants, that is capable of developing into a new individual under favorable conditions.

A spore serves as a survival mechanism, allowing organisms to withstand harsh environmental conditions like drought, heat, or cold. It remains dormant until conditions improve, at which point it germinates and grows into a new organism.

While both spores and seeds are reproductive structures, spores are typically unicellular and produced by non-flowering plants, fungi, and some bacteria. Seeds, on the other hand, are multicellular and produced by flowering plants, containing an embryo and stored food.

Some spores, such as those from certain fungi (e.g., mold) or bacteria (e.g., anthrax), can be harmful to humans if inhaled or ingested. However, many spores are harmless and play essential roles in ecosystems.