Yeast spore germination is a critical process in the life cycle of yeast, marking the transition from a dormant spore to a metabolically active vegetative cell. During germination, the spore undergoes a series of coordinated events, including the breakdown of the spore wall, reactivation of metabolic pathways, and resumption of cell growth and division. This process is triggered by favorable environmental conditions, such as the availability of nutrients and water, and is tightly regulated to ensure successful revival. Understanding the mechanisms of yeast spore germination not only provides insights into yeast biology but also has practical implications in industries such as brewing, baking, and biotechnology, where yeast plays a vital role.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Trigger for Germination | Nutrient availability, favorable environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH) |

| Initial Event | Spore wall softening due to enzymatic degradation of spore wall components |

| Water Uptake | Rapid absorption of water (imbibition), leading to spore swelling |

| Metabolic Activation | Resumption of metabolic activities, including ATP production and protein synthesis |

| Nuclear Division | Exit from quiescence, followed by DNA replication and cell division (budding) |

| Germ Tube Formation | Emergence of a germ tube from the spore, marking the beginning of vegetative growth |

| Enzyme Secretion | Release of hydrolytic enzymes to break down external nutrients |

| Energy Source Utilization | Utilization of stored reserves (e.g., glycogen, trehalose) and external nutrients |

| Cell Wall Remodeling | Synthesis of new cell wall components to support growth |

| Transition to Vegetative Growth | Development into a yeast cell capable of budding and colony formation |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Germination is inhibited by stressors like extreme temperatures or toxins |

| Timeframe | Typically occurs within hours to days, depending on species and conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Wall Breakdown: Enzymes degrade the spore wall, allowing water and nutrients to enter

- Metabolic Activation: Dormant spores resume metabolic activities, including respiration and protein synthesis

- Germ Tube Emergence: A germ tube forms and elongates, marking the start of vegetative growth

- Nuclear Division: The spore nucleus undergoes mitosis, preparing for cell division and growth

- Nutrient Uptake: Spores absorb nutrients from the environment to support germination and development

Spore Wall Breakdown: Enzymes degrade the spore wall, allowing water and nutrients to enter

Yeast spore germination begins with a critical event: the breakdown of the spore wall. This rigid structure, composed of complex polysaccharides and proteins, serves as a protective barrier during dormancy. However, for germination to occur, this barrier must be breached. Enzymes, specifically chitinases and glucanases, play a pivotal role in this process. These enzymes are produced by the spore itself and are activated under favorable conditions, such as the presence of water and nutrients. As they degrade the chitin and glucan components of the spore wall, the once-impermeable barrier becomes permeable, allowing essential resources to enter and initiate metabolic activity.

Consider the analogy of a locked door. The spore wall is the door, and the enzymes are the key. Without the key, the door remains shut, and the spore remains dormant. Once the enzymes unlock the door, the spore can "wake up" and begin the process of growth. This enzymatic action is highly regulated, ensuring that germination occurs only when conditions are optimal. For instance, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the presence of specific sugars and a suitable pH triggers the production of these enzymes, highlighting the precision of this biological mechanism.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore wall breakdown is crucial for industries like baking and brewing, where yeast germination directly impacts product quality. For example, in bread-making, ensuring that yeast spores germinate efficiently can improve dough rise and texture. To facilitate this, bakers often pre-soak yeast in warm water (35–40°C) with a small amount of sugar, creating an environment that mimics optimal germination conditions. This simple step activates the enzymes more rapidly, leading to faster and more consistent results. Similarly, in brewing, controlling the temperature and nutrient availability during yeast propagation can enhance spore wall breakdown, improving fermentation efficiency.

A comparative analysis reveals that not all yeast species germinate in the same way. For instance, *Schizosaccharomyces pombe* requires a higher concentration of glucose to activate its spore wall-degrading enzymes compared to *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. This difference underscores the importance of tailoring conditions to the specific yeast strain being used. Additionally, environmental factors like pH and oxygen levels can influence enzyme activity, further complicating the process. Researchers are exploring ways to manipulate these factors to optimize germination rates, particularly in industrial settings where consistency is key.

In conclusion, spore wall breakdown is a finely tuned process driven by enzymatic activity. By understanding the mechanisms and conditions that activate these enzymes, we can harness yeast germination more effectively, whether in a laboratory, bakery, or brewery. Practical tips, such as using warm water and specific nutrients, can significantly enhance germination efficiency. As research continues to uncover the intricacies of this process, its applications will only expand, benefiting both scientific inquiry and everyday practices.

Mastering Mushroom Identification: A Step-by-Step Guide to Making Spore Prints

You may want to see also

Metabolic Activation: Dormant spores resume metabolic activities, including respiration and protein synthesis

Yeast spore germination is a complex process that marks the transition from a dormant, resilient state to an active, metabolically vibrant cell. Central to this transformation is metabolic activation, where dormant spores resume essential activities like respiration and protein synthesis. This resumption is not merely a switch flipped but a carefully orchestrated sequence of events, each step critical for the spore's survival and growth.

Consider the analogy of waking from a deep sleep. Just as a person gradually resumes normal functions after rest, yeast spores reinitiate metabolic processes in a precise order. Respiration, the cellular process of generating energy from nutrients, is among the first activities to restart. This involves the uptake of glucose and its conversion into ATP, the cell's energy currency. For instance, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, glucose concentrations as low as 0.1% (w/v) can trigger this metabolic awakening, though optimal germination often requires 2% (w/v) glucose in laboratory settings. This energy is crucial for powering subsequent steps, such as the synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids.

Protein synthesis is another cornerstone of metabolic activation. Dormant spores contain pre-existing mRNA transcripts, but new protein production is essential for growth and division. Ribosomes, the cell's protein factories, become active, translating mRNA into enzymes, structural proteins, and other molecules necessary for cellular function. Studies show that inhibitors of protein synthesis, like cycloheximide, can halt germination, underscoring its importance. Practically, ensuring nutrient availability—particularly nitrogen sources like ammonium sulfate (0.5% w/v)—is vital, as protein synthesis relies on amino acid precursors.

The interplay between respiration and protein synthesis is a delicate balance. Respiration provides the energy and reducing power (NADH, ATP) required for protein synthesis, while newly synthesized proteins, such as enzymes involved in metabolic pathways, further enhance respiratory efficiency. This feedback loop amplifies metabolic activity, propelling the spore toward full cellular function. For researchers or brewers aiming to optimize germination, monitoring oxygen availability (aerobic conditions are essential) and maintaining a temperature of 30°C—ideal for *S. cerevisiae*—can significantly enhance metabolic activation.

In summary, metabolic activation during yeast spore germination is a finely tuned process, reliant on the sequential and interdependent resumption of respiration and protein synthesis. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on fundamental biology but also offers practical insights for industries like brewing and biotechnology, where controlling germination is key to productivity. By manipulating environmental factors like nutrient availability and temperature, one can effectively guide dormant spores toward a metabolically active state, ensuring successful growth and function.

How Long Do Mold Spores Stay Airborne and Pose Risks?

You may want to see also

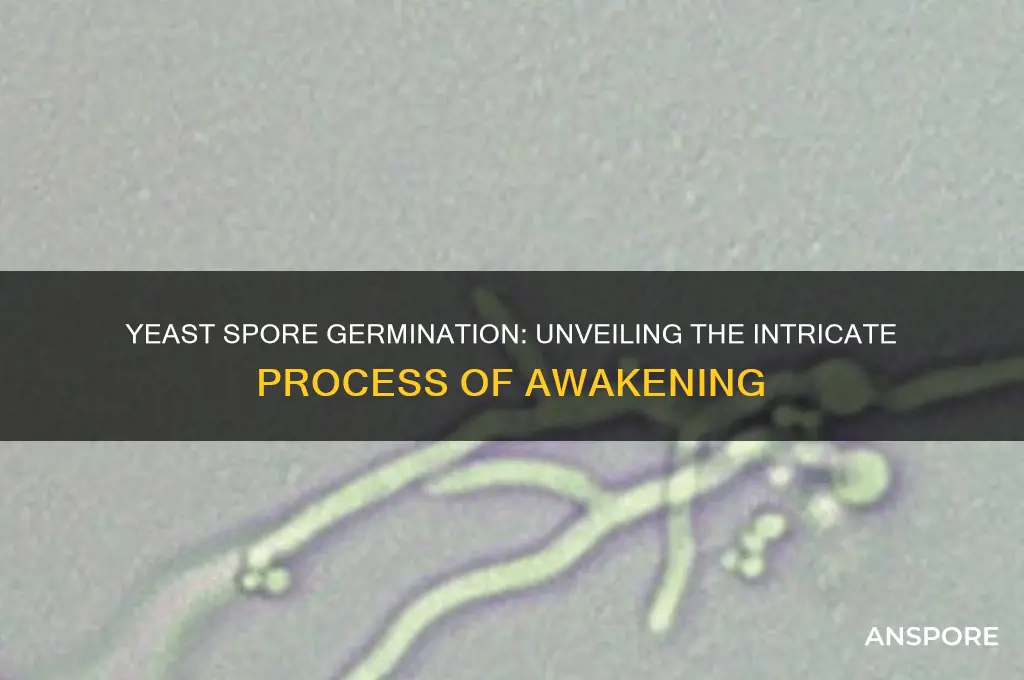

Germ Tube Emergence: A germ tube forms and elongates, marking the start of vegetative growth

Yeast spore germination is a fascinating process that marks the transition from a dormant state to active growth. One of the most critical stages in this transformation is germ tube emergence, where a small, tube-like structure forms and elongates from the spore. This event is not merely a physical change but a pivotal moment that signals the beginning of vegetative growth, setting the stage for the yeast to thrive and multiply.

From an analytical perspective, germ tube emergence is a highly regulated process influenced by environmental cues such as temperature, nutrient availability, and pH. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a common yeast species, typically initiates germ tube formation at temperatures between 25°C and 37°C. The presence of specific nutrients, particularly glucose and nitrogen sources, accelerates this process. Understanding these conditions is crucial for optimizing yeast cultivation in both laboratory and industrial settings. For example, in baking, ensuring the dough is at an optimal temperature (around 30°C) can enhance germ tube emergence, leading to better leavening and texture in bread.

Instructively, inducing germ tube emergence in yeast spores requires careful manipulation of the environment. Start by suspending the spores in a nutrient-rich medium, such as yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth, at a concentration of 10^6 to 10^7 spores per milliliter. Incubate the suspension at 30°C for 1–2 hours, monitoring for the appearance of germ tubes under a microscope at 400x magnification. A practical tip is to add 10% fetal bovine serum to the medium, as it has been shown to enhance germ tube formation in some yeast species. Avoid overexposure to high temperatures or nutrient deprivation, as these can inhibit germination.

Comparatively, germ tube emergence in yeast shares similarities with hyphal formation in filamentous fungi, yet the mechanisms differ. While both processes involve polarized growth, yeast germ tubes are typically unbranched and serve as precursors to budding cells, whereas fungal hyphae are branched and extend for nutrient acquisition. This distinction highlights the unique adaptive strategies of yeast, which prioritize rapid cell division over extensive exploration of the environment. Such comparisons underscore the importance of germ tube emergence as a specialized feature of yeast germination.

Descriptively, the germ tube itself is a marvel of cellular organization. It begins as a small bulge on the spore’s surface, gradually elongating into a cylindrical structure. This growth is driven by the polarized secretion of cell wall components and the directed transport of vesicles to the emerging tip. Over time, the germ tube becomes the site of the first bud, marking the resumption of the yeast’s life cycle. Observing this process under a microscope reveals a dynamic interplay of cellular machinery, a testament to the resilience and adaptability of yeast.

In conclusion, germ tube emergence is a cornerstone of yeast spore germination, bridging dormancy and active growth. By understanding its mechanisms and optimizing conditions, researchers and practitioners can harness this process for various applications, from biotechnology to food production. Whether in a lab or a kitchen, the emergence of the germ tube is a small yet profound event that underscores the complexity and beauty of microbial life.

Lysol's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Ringworm Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Nuclear Division: The spore nucleus undergoes mitosis, preparing for cell division and growth

Yeast spore germination is a complex process that marks the transition from a dormant spore to a metabolically active yeast cell. Central to this transformation is nuclear division, a critical step that ensures the spore's genetic material is replicated and distributed accurately, setting the stage for cell division and growth. This process, known as mitosis, is a highly regulated sequence of events that unfolds within the spore nucleus, laying the foundation for the development of a new yeast cell.

The Mitosis Mechanism: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Mitosis in yeast spores can be divided into four distinct phases: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. During prophase, the spore nucleus condenses, and the nuclear envelope breaks down, allowing the mitotic spindle to form. This spindle, composed of microtubules, plays a crucial role in segregating the duplicated chromosomes. In metaphase, the chromosomes align along the spindle equator, ensuring proper distribution to the daughter nuclei. Anaphase follows, where the sister chromatids are pulled apart and migrate to opposite poles of the cell. Finally, in telophase, the nuclear envelope reforms around each set of chromosomes, and the cell prepares for cytokinesis, the physical separation of the two daughter cells.

Comparative Analysis: Yeast vs. Other Eukaryotes

While the fundamental principles of mitosis are conserved across eukaryotes, yeast exhibits unique adaptations that optimize this process for its unicellular lifestyle. For instance, yeast cells often undergo a rapid succession of cell cycles, known as "closed" mitosis, where the nuclear envelope remains intact during early stages of division. This contrasts with the "open" mitosis observed in many multicellular organisms, where the nuclear envelope disassembles completely. Such adaptations highlight the efficiency and specialization of yeast's nuclear division process, enabling rapid growth and response to environmental changes.

Practical Implications: Harnessing Mitosis in Biotechnology

Understanding the intricacies of nuclear division during yeast spore germination has significant implications for biotechnology and industry. For example, in the production of biofuels and pharmaceuticals, optimizing yeast growth rates is essential for maximizing yield. By manipulating the cell cycle, researchers can enhance mitotic efficiency, leading to faster proliferation of yeast cells. Techniques such as synchronizing cell cultures or modulating gene expression of cell cycle regulators (e.g., cyclins and CDKs) can be employed to achieve this. Additionally, studying mitosis in yeast provides a model system for investigating human diseases related to cell division, such as cancer, where dysregulated mitosis is a hallmark.

Cautions and Considerations: Ensuring Accurate Chromosome Segregation

Despite its efficiency, mitosis during yeast spore germination is not without risks. Errors in chromosome segregation can lead to aneuploidy, a condition where cells have an abnormal number of chromosomes. Aneuploid yeast cells often exhibit reduced fitness and can accumulate genetic instability over time. To mitigate these risks, yeast has evolved robust checkpoint mechanisms, such as the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which monitors proper chromosome attachment to the mitotic spindle. Ensuring the integrity of these checkpoints is vital for maintaining genomic stability, particularly in industrial strains subjected to selective pressures or genetic engineering. By prioritizing accurate nuclear division, researchers can safeguard the long-term viability and productivity of yeast cultures.

Understanding Isolated Spore Syringes: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Cultivation

You may want to see also

Nutrient Uptake: Spores absorb nutrients from the environment to support germination and development

Yeast spore germination is a nutrient-dependent process, and the availability of essential elements in the environment is a critical factor in determining the success of this transformation. During germination, spores undergo a series of metabolic changes, reactivating cellular processes that require a significant amount of energy and raw materials. This is where nutrient uptake plays a pivotal role. The spore's ability to absorb and utilize nutrients from its surroundings is a finely tuned mechanism, ensuring that the developing yeast cell has the necessary resources for growth and division.

The Nutrient Acquisition Process:

Imagine a dormant yeast spore as a sleeping giant, waiting for the right conditions to awaken. When the environment provides the necessary nutrients, the spore springs into action. This activation involves the rapid uptake of nutrients, primarily through specialized transport systems in the spore's membrane. These transporters are like gatekeepers, allowing essential molecules such as sugars, amino acids, and minerals to enter the spore. For instance, glucose, a simple sugar, is a preferred energy source for yeast and is actively transported into the spore, fueling the metabolic processes required for germination.

A Delicate Balance:

The efficiency of nutrient uptake is a delicate balance between the spore's needs and the environment's offerings. Too little nutrients, and the spore may remain dormant or struggle to complete germination. Excessive nutrient availability, on the other hand, can lead to rapid but uncontrolled growth, potentially compromising the yeast's health. Optimal nutrient concentrations vary depending on the yeast species, but generally, a balanced mixture of carbon sources (sugars), nitrogen compounds (amino acids, ammonium), and essential minerals (e.g., phosphorus, magnesium) is required. For example, a common laboratory medium for yeast germination, YPD (Yeast Extract-Peptone-Dextrose), contains 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose, providing a rich source of nutrients for robust germination.

Practical Considerations:

In practical terms, understanding nutrient uptake is crucial for various applications, from brewing and baking to biotechnology. In brewing, for instance, the germination of yeast spores is a critical step in the fermentation process. Brewers carefully control the nutrient composition of the wort (the sugary liquid extracted from grains) to ensure healthy yeast growth and efficient fermentation. Similarly, in baking, the availability of nutrients in the dough affects the yeast's ability to leaven bread, impacting the final product's texture and flavor. By manipulating nutrient levels, one can control the rate and extent of yeast germination, thereby influencing the overall outcome of these processes.

Optimizing Germination:

To optimize yeast spore germination, one must consider the following: first, identify the specific nutrient requirements of the yeast species in question. Different yeasts have varying preferences and tolerances. Second, ensure a balanced nutrient supply, avoiding both deficiencies and excesses. This may involve adjusting the concentration of nutrients in the growth medium or environment. Lastly, monitor environmental factors such as temperature and pH, as these can influence nutrient availability and uptake. For example, slightly acidic conditions (pH 4-5) often enhance nutrient solubility and uptake in yeast. By mastering these aspects of nutrient uptake, one can effectively control and enhance yeast spore germination, leading to successful applications in various industries.

Proper Storage Tips for Spore Syringes: Maximize Longevity and Viability

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yeast spore germination is typically triggered by favorable environmental conditions, such as the presence of nutrients, water, and optimal temperature. Additionally, changes in pH or osmotic pressure can also initiate the process.

Yeast spore germination involves three main stages: (1) activation, where the spore rehydrates and metabolic activity resumes; (2) germ tube emergence, where a small tube begins to form; and (3) outgrowth, where the germ tube elongates and develops into a new yeast cell.

The duration of yeast spore germination varies depending on the species and environmental conditions, but it typically takes between 2 to 12 hours for the germ tube to emerge and several more hours for the spore to fully develop into a vegetative cell.

The cell wall undergoes significant remodeling during germination. Enzymes break down the spore wall, allowing the germ tube to emerge. New cell wall components are synthesized to support the growing yeast cell, ensuring structural integrity during the transition from spore to vegetative state.