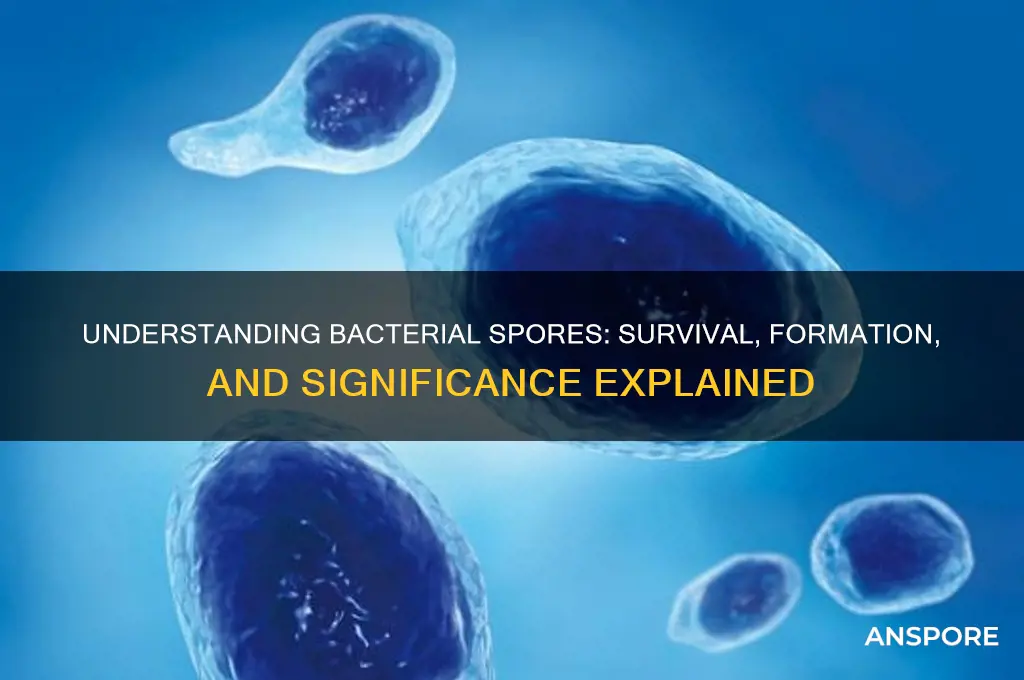

A bacterial spore is a highly resistant, dormant cell structure produced by certain bacteria, primarily in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, as a survival mechanism in harsh environmental conditions. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are metabolically inactive and possess a thick, protective outer layer that enables them to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. This remarkable resilience allows spores to persist in the environment for extended periods, often reactivating into vegetative cells when conditions become favorable. Their ability to survive disinfection and sterilization processes makes them a significant concern in fields such as food safety, healthcare, and biotechnology. Understanding bacterial spores is crucial for developing effective strategies to control and eliminate them in various industries.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A dormant, highly resistant cell type produced by certain bacteria in response to adverse environmental conditions. |

| Size | Typically 0.5 to 1.5 μm in diameter, smaller than the vegetative bacterial cell. |

| Shape | Generally oval or spherical, often located within or adjacent to the bacterial cell. |

| Composition | Primarily composed of dipicolinic acid (DPA), calcium, DNA, RNA, and proteins, surrounded by a spore coat and exosporium. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, chemicals, and enzymes due to the spore coat and low water content. |

| Metabolism | Metabolically inactive, with minimal energy consumption and no growth or reproduction. |

| Germination | Can revert to vegetative form under favorable conditions, resuming metabolic activity and replication. |

| Formation | Formed through sporulation, a complex process involving DNA replication, septum formation, and spore coat synthesis. |

| Location | Found in Gram-positive bacteria, notably in genera like Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Ecological Role | Allows bacteria to survive harsh environments, ensuring long-term survival and dispersal. |

| Medical Relevance | Important in food spoilage, sterilization processes, and as potential agents of bioterrorism (e.g., Bacillus anthracis). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Endospore creation process within bacterial cell for survival in harsh conditions

- Structure: Multilayered, durable coat protects DNA and enzymes from damage

- Resistance: Withstands heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, ensuring long-term survival

- Germination: Spores revive and grow into vegetative cells under favorable conditions

- Significance: Essential for bacterial survival, food spoilage, and medical sterilization challenges

Spore Formation: Endospore creation process within bacterial cell for survival in harsh conditions

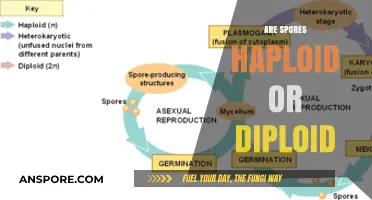

Bacterial spores are nature's ultimate survival capsules, enabling certain bacteria to endure extreme conditions that would otherwise be lethal. Among these, endospores stand out as a remarkable example of cellular adaptation. Formed within the bacterial cell, endospores are highly resistant structures that safeguard the organism's genetic material and a minimal set of enzymes necessary for revival. This process, known as sporulation, is a complex, multi-step transformation that ensures bacterial survival in environments characterized by high temperatures, desiccation, radiation, or chemical exposure.

The endospore creation process begins with an environmental signal, such as nutrient depletion, triggering a series of genetic and morphological changes within the bacterial cell. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for studying sporulation, the process starts with the activation of the spo0A gene, which acts as a master regulator. The cell then undergoes asymmetric division, producing a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. This division is not merely a split but a carefully orchestrated event where the mother cell engulfs the forespore, creating a double-membrane structure. The forespore then develops a thick, multi-layered coat composed of proteins, peptidoglycan, and lipids, which provides the structural integrity and resistance properties essential for survival.

One of the most fascinating aspects of endospore formation is the deposition of a spore-specific cortex layer rich in peptidoglycan, which surrounds the forespore. This layer, combined with the coat, contributes to the spore's resistance to heat, enzymes, and chemicals. For example, endospores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling water for hours, making them a significant concern in food preservation. Additionally, the calcium dipicolinate complex found within the spore core plays a crucial role in stabilizing DNA and proteins during dormancy, further enhancing resistance to harsh conditions.

Practical applications of understanding endospore formation extend to various fields, including medicine, food safety, and biotechnology. For instance, sterilizing medical equipment requires exposure to temperatures of at least 121°C for 15–30 minutes in an autoclave to ensure the destruction of endospores, which are more resistant than their vegetative counterparts. In the food industry, controlling sporulation in pathogens like *Bacillus cereus* is critical to preventing foodborne illnesses. Conversely, harnessing the resilience of endospores can be beneficial in biotechnology, such as using them as carriers for vaccines or enzymes in extreme environments.

In conclusion, endospore formation is a testament to the ingenuity of bacterial survival strategies. By encapsulating the essence of life within a protective shell, bacteria ensure their persistence across millennia and environments. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for microbial life but also equips us with tools to combat pathogens and leverage their capabilities for human benefit. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or factory, the principles of sporulation remain a cornerstone of both challenge and opportunity.

Can Lysol Spray Effectively Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Structure: Multilayered, durable coat protects DNA and enzymes from damage

Bacterial spores are nature's time capsules, engineered to withstand extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. At the heart of their resilience lies a multilayered, durable coat that acts as a fortress, safeguarding the spore's genetic material and essential enzymes from damage. This intricate structure is not just a passive shield but a dynamic system designed to ensure survival across millennia, if necessary.

Consider the layers of a bacterial spore as a series of specialized barriers, each with a unique function. The outermost layer, the exosporium, is akin to a protective skin, often adorned with hair-like structures that aid in attachment and dispersal. Beneath this lies the spore coat, a robust and chemically resistant layer composed of proteins and peptides. This coat is the primary defense against environmental assaults, from desiccation to UV radiation. Deeper still, the cortex layer, rich in peptidoglycan, provides additional structural integrity and acts as a dehydration buffer, further insulating the spore's core.

The brilliance of this design becomes evident when examining its protective mechanisms. For instance, the spore coat’s cross-linked proteins resist enzymatic degradation, making it impervious to many predators and environmental enzymes. This layer also contains calcium dipicolinate, a compound that stabilizes the spore’s DNA by binding water molecules, preventing them from damaging the genetic material during dehydration. Such adaptations ensure that the spore’s DNA and enzymes remain intact, even in conditions that would denature most biological molecules.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast. In the food industry, understanding spore structure helps develop more effective sterilization techniques, as traditional methods like boiling may not penetrate the spore coat. For instance, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes is often required to destroy spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, a common food contaminant. Similarly, in medicine, spore resistance informs the design of antibiotics and disinfectants, ensuring they target the spore’s vulnerabilities.

In essence, the multilayered coat of a bacterial spore is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, a testament to the ingenuity of life’s survival strategies. By studying its structure, we not only gain insights into microbial resilience but also unlock practical solutions for preserving food, treating infections, and even designing long-term storage systems for biological materials. This coat is more than a barrier—it’s a blueprint for endurance.

Can Alcohol Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? Facts and Myths Revealed

You may want to see also

Resistance: Withstands heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals, ensuring long-term survival

Bacterial spores are nature's ultimate survivalists, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Their resistance to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals is not just a passive trait but an active, multi-layered defense mechanism. Consider this: a bacterial spore can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C, doses of UV radiation that would fry DNA, and environments devoid of water for decades. This resilience is rooted in their unique structure—a thick, multi-layered coat fortified with calcium dipicolinate and a dehydrated cytoplasm that minimizes chemical reactivity. Understanding these adaptations isn’t just academic; it’s critical for industries like food safety, healthcare, and space exploration, where spores pose both challenges and opportunities.

To neutralize bacterial spores, heat is often the first line of defense, but it’s not as simple as turning up the thermostat. Autoclaves, for instance, use steam under pressure (121°C for 15–30 minutes) to penetrate the spore’s robust coat and denature its proteins. However, some spores, like those of *Clostridium botulinum*, require even harsher conditions—up to 130°C for extended periods. Radiation, another spore-killer, works by shattering the DNA within, but spores’ DNA is compacted and protected by small, acid-soluble proteins (SASPs), necessitating higher doses of gamma or UV radiation (e.g., 10–20 kGy for sterilization). These methods aren’t foolproof, though; spores’ ability to repair DNA post-exposure underscores their tenacity.

Desiccation, or extreme dryness, is another challenge spores not only withstand but exploit. By reducing metabolic activity to near-zero, spores can persist in arid environments for centuries. This is why ancient spores have been revived from amber and salt crystals, their genetic material intact. For industries like pharmaceuticals, this means desiccation isn’t just a preservative technique but a double-edged sword—it halts spoilage but also preserves spores’ viability. Practical tip: when storing dry goods, maintain humidity below 10% to discourage spore germination, but recognize that even this won’t eliminate them entirely.

Chemicals, too, struggle to breach the spore’s defenses. Common disinfectants like ethanol and quaternary ammonium compounds are ineffective against spores due to their impermeable coat. Only sporicides like hydrogen peroxide (at 6–35% concentration) or formaldehyde (in vapor form) can penetrate and disrupt spore metabolism. Even then, prolonged exposure (e.g., 6–12 hours for formaldehyde) is required. This chemical resistance is why spores are the gold standard for testing sterilization protocols—if a process kills spores, it’s assumed to kill everything else.

The takeaway? Bacterial spores are not just resistant; they’re a masterclass in survival. Their ability to withstand heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals isn’t random but a product of evolutionary precision. For practitioners in sterilization, preservation, or infection control, understanding these mechanisms isn’t optional—it’s essential. Whether you’re autoclaving lab equipment, preserving food, or designing spacecraft, spores demand respect and strategy. After all, what survives today evolves tomorrow.

Does Vinegar Effectively Kill Mold Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination: Spores revive and grow into vegetative cells under favorable conditions

Bacterial spores are dormant, highly resistant structures produced by certain bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions. While in this state, they can endure extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals that would otherwise destroy their vegetative counterparts. However, the true marvel of spores lies in their ability to revive and grow into active, metabolizing cells when conditions improve—a process known as germination. This transformation is not merely a return to life but a strategic shift from survival mode to proliferation, ensuring the bacterium’s long-term success.

Germination begins when a spore detects favorable conditions, such as the presence of nutrients, appropriate temperature, and pH levels. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require nutrients like L-valine and purine nucleosides to initiate germination. Once triggered, the spore’s protective layers—the coat, cortex, and exosporium—undergo changes. The cortex, composed of peptidoglycan, absorbs water and swells, weakening the structure. Simultaneously, the coat proteins rearrange, allowing for the release of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a molecule crucial for spore dormancy. This process is tightly regulated, ensuring that germination occurs only when survival is likely.

The steps of germination are precise and energy-efficient. First, germination receptors on the spore’s surface bind to specific nutrients or chemicals, signaling the start of the process. Next, the spore’s core rehydrates, and its metabolism reactivates. The degradation of DPA and the resumption of DNA replication mark the transition from dormancy to active growth. Within minutes to hours, depending on the species and conditions, the spore sheds its protective layers and emerges as a vegetative cell, ready to divide and colonize its environment.

Practical applications of spore germination are vast, particularly in food safety and medicine. For instance, understanding germination inhibitors can help prevent food spoilage caused by spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum*. Conversely, controlled germination is essential in biotechnology, where spores are used as delivery vehicles for vaccines or enzymes. To harness this process effectively, researchers often manipulate environmental factors such as temperature (typically 30–37°C for optimal germination) and nutrient availability. For home preservation, maintaining low temperatures (below 4°C) and avoiding cross-contamination can prevent spore germination in canned foods.

In comparison to other microbial survival strategies, spore germination stands out for its efficiency and resilience. Unlike cysts or biofilms, spores can remain viable for centuries, waiting for the perfect moment to revive. This adaptability makes them both a challenge and an opportunity. While they pose risks in industries like healthcare and food production, their unique properties inspire innovations in drug delivery and environmental cleanup. By studying germination, scientists unlock not only ways to combat harmful bacteria but also tools to harness their potential for good.

How Long Do Mold Spores Survive on Your Clothes?

You may want to see also

Significance: Essential for bacterial survival, food spoilage, and medical sterilization challenges

Bacterial spores are nature's ultimate survival capsules, enabling certain bacteria to endure extreme conditions that would otherwise be lethal. These dormant, highly resistant structures can withstand desiccation, radiation, and extreme temperatures, ensuring bacterial persistence in environments where active growth is impossible. This resilience is a double-edged sword: while it guarantees bacterial survival, it also poses significant challenges in food preservation and medical sterilization.

Consider the food industry, where bacterial spores are a leading cause of spoilage and foodborne illness. *Clostridium botulinum*, for instance, produces spores that can survive in canned foods, even under high-temperature processing. If these spores germinate and grow, they release botulinum toxin, a potent neurotoxin responsible for botulism. To mitigate this risk, the food industry employs stringent sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to destroy spores. However, not all foods can withstand such harsh conditions, necessitating alternative methods like high-pressure processing or the addition of preservatives. Practical tip: When canning at home, always follow USDA guidelines, including using a pressure canner for low-acid foods to ensure spore destruction.

In medical settings, bacterial spores present a critical challenge to sterilization efforts. Surgical instruments and medical devices must be free of all microbial life, including spores, to prevent infections. Traditional sterilization methods, like steam autoclaving, are effective but require precise conditions (e.g., 134°C for 3–15 minutes) to ensure spore inactivation. For heat-sensitive materials, alternatives like ethylene oxide gas or hydrogen peroxide plasma are used, though these methods are more time-consuming and costly. Caution: Improper sterilization can lead to outbreaks, as seen in cases of *Clostridium difficile* infections in hospitals, where spores survived routine cleaning protocols.

The significance of bacterial spores extends beyond immediate practical challenges, highlighting the evolutionary brilliance of microbial life. Their ability to remain dormant for decades, only to revive when conditions improve, underscores the need for continuous innovation in sterilization and preservation technologies. For example, researchers are exploring spore-targeting antimicrobial agents and novel sterilization techniques, such as cold plasma treatment, to address current limitations. Takeaway: Understanding spore biology is not just an academic exercise—it’s a critical step toward safeguarding public health and ensuring the longevity of food and medical supplies.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A bacterial spore is a dormant, highly resistant cell type produced by certain bacteria, primarily in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to survive harsh environmental conditions.

A bacterial spore is metabolically inactive, has a thick protective coat, and is highly resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals, whereas a vegetative bacterial cell is metabolically active, grows and divides, but is more susceptible to environmental stresses.

Bacteria form spores as a survival mechanism in response to unfavorable conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, allowing them to persist until conditions improve.

Yes, some bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis*, can cause diseases when they germinate into vegetative cells and produce toxins or multiply in a host.

Bacterial spores are destroyed by extreme methods such as autoclaving (high-pressure steam), prolonged exposure to high temperatures, or treatment with strong chemical sterilants like bleach or hydrogen peroxide.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)