Spore biology is a fascinating field of study that explores the unique reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria. Spores are highly specialized cells designed to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as drought, extreme temperatures, or lack of nutrients, allowing the organism to persist and disperse over time and space. These resilient structures play a crucial role in the life cycles of many species, enabling them to reproduce asexually, colonize new habitats, and ensure their long-term survival. Understanding spore biology not only sheds light on the evolutionary strategies of diverse organisms but also has practical applications in agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology, making it a vital area of research in the biological sciences.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A spore is a reproductive structure produced by fungi, plants (especially ferns, mosses, and liverworts), and some bacteria. It is capable of developing into a new individual without fusion with another cell. |

| Size | Typically small, ranging from 1 to 50 micrometers in diameter, depending on the species. |

| Structure | Usually unicellular, with a protective outer wall (e.g., exine in plant spores) to withstand harsh environmental conditions. |

| Function | Primarily for asexual reproduction and dispersal, allowing organisms to survive unfavorable conditions (e.g., drought, heat, cold). |

| Dispersal | Dispersed by wind, water, animals, or other means to reach new habitats. |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods (years to centuries) until conditions are favorable for germination. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals due to their robust cell walls and metabolic inactivity. |

| Types | Fungal Spores: Sporangiospores, conidia, zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores; Plant Spores: Spores from ferns, mosses, liverworts, and some seedless vascular plants; Bacterial Spores: Endospores (e.g., in Bacillus and Clostridium species). |

| Germination | Activates when environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, temperature, light) trigger metabolic activity and growth. |

| Ecological Role | Essential for the survival and dispersal of spore-producing organisms, contributing to biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. |

| Medical Relevance | Some bacterial spores (e.g., Clostridium botulinum, Bacillus anthracis) are pathogenic and can cause diseases in humans and animals. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: How spores develop in plants, fungi, and bacteria through specialized cell division

- Types of Spores: Classification based on origin, function, and organisms (e.g., endospores, zygospores)

- Spore Function: Role in reproduction, survival, and dispersal across harsh environments

- Spore Structure: Protective layers, genetic material, and adaptations for longevity and resistance

- Spore Germination: Conditions and mechanisms triggering spore activation and growth resumption

Spore Formation Process: How spores develop in plants, fungi, and bacteria through specialized cell division

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, enabling plants, fungi, and bacteria to endure harsh conditions and disperse across environments. Their formation hinges on specialized cell division processes tailored to each organism’s needs. In plants, particularly ferns and mosses, spore development occurs via meiosis in structures like sporangia, producing haploid cells that can grow into new individuals under favorable conditions. Fungi, such as molds and mushrooms, form spores through mitosis or meiosis, depending on their life cycle stage, often within structures like asci or basidia. Bacteria, notably those in the genus *Bacillus*, create endospores through a complex process involving DNA replication, septum formation, and spore coat synthesis, ensuring resistance to extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals.

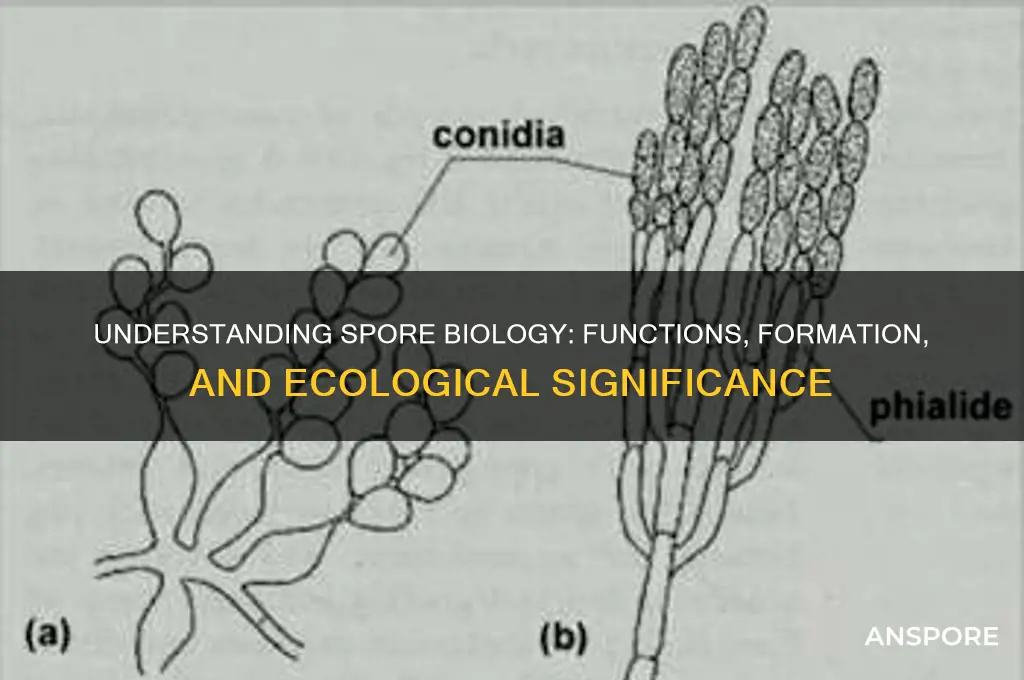

Consider the instructive steps in bacterial endospore formation, a marvel of cellular engineering. It begins with DNA replication and segregation, followed by the formation of a septum that partitions the cell into a larger mother cell and smaller forespore. The forespore then develops a protective coat and cortex, rich in peptidoglycan, while the mother cell degrades, releasing the mature endospore. This process, though energy-intensive, ensures the bacterium’s survival for centuries. For fungi, spore formation is equally strategic. In yeasts like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, spores arise during meiosis, triggered by nutrient deprivation, while molds like *Aspergillus* produce asexual spores (conidia) through repeated mitotic divisions, enabling rapid colonization of new habitats.

A comparative analysis reveals the efficiency of spore formation across kingdoms. Plant spores are lightweight and aerodynamic, optimized for wind dispersal, while fungal spores often have adhesive properties or are carried by insects. Bacterial endospores, however, prioritize durability over mobility, capable of withstanding autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes. This diversity underscores the adaptive brilliance of spores, each tailored to its organism’s ecological niche. For instance, fern spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for the right moisture and light conditions, whereas bacterial endospores can germinate within hours upon sensing nutrient availability.

Practical applications of spore biology abound. In agriculture, understanding plant spore dispersal helps optimize crop pollination and control invasive species. Fungal spores are harnessed in biotechnology for enzyme production and antibiotic synthesis, while bacterial endospores serve as models for studying extremophile survival mechanisms. For hobbyists, cultivating spore-producing organisms like mushrooms or ferns requires controlling humidity, temperature, and light—for example, maintaining 70-80% humidity for mushroom spore germination. Caution is advised when handling bacterial spores, as their resilience poses contamination risks in lab and industrial settings.

In conclusion, spore formation is a testament to life’s ingenuity, blending precision, resilience, and adaptability. Whether through meiosis in plants, mitosis in fungi, or endospore differentiation in bacteria, this process ensures the continuity of species across time and space. By studying these mechanisms, we unlock insights into evolution, ecology, and biotechnology, while gaining practical tools for agriculture, medicine, and conservation. Spore biology is not just a scientific curiosity—it’s a blueprint for survival.

How Far Can Mold Spores Travel: Unveiling Their Airborne Journey

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Classification based on origin, function, and organisms (e.g., endospores, zygospores)

Spores are microscopic, dormant structures produced by various organisms to survive harsh conditions, disperse, or reproduce. Their classification hinges on origin, function, and the organisms that produce them. For instance, endospores, formed within bacterial cells, are renowned for their resilience, enduring extremes of heat, radiation, and chemicals. In contrast, zygospores, produced by certain fungi and algae, result from the fusion of gametes and serve primarily for sexual reproduction. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for fields like microbiology, ecology, and biotechnology.

Consider the origin of spores. Endospores, exclusive to Gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are formed internally as a protective shell around the bacterium’s DNA and essential enzymes. This process, called sporulation, is triggered by nutrient depletion. Zygospores, on the other hand, arise from the fusion of two compatible gametangia in organisms like zygomycetes fungi. This external formation highlights a stark contrast in developmental mechanisms. Another example is conidia, asexual spores produced externally on specialized structures in fungi like *Aspergillus*. Their origin on the organism’s surface facilitates rapid dispersal.

Functionally, spores serve diverse roles. Endospores are survival structures, enabling bacteria to persist in environments lethal to their vegetative forms. Zygospores, however, are reproductive, ensuring genetic diversity through sexual fusion. Sporangiospores, produced by fungi like *Rhizopus*, are asexual and aid in dispersal, while cysts, formed by parasites like *Giardia*, protect the organism during transmission between hosts. Each type’s function dictates its structure and resistance mechanisms, making them adaptable to specific ecological niches.

Organism-specific spores reveal fascinating adaptations. Meiospores, produced by plants like ferns and mosses, are the result of meiosis and are crucial for their life cycles. In algae, zoospores are motile, using flagella to swim toward favorable environments. Teliospores, found in rust fungi, are thick-walled structures that overwinter, ensuring survival across seasons. These examples underscore how spore types are finely tuned to the needs of their producers, from dispersal to dormancy.

Practical applications of spore classification abound. For instance, understanding endospores is vital in food safety, as they can survive sterilization processes, leading to contamination. Zygospores are studied in agriculture to improve fungal resistance in crops. Hobbyists cultivating mushrooms benefit from knowing conidia’s role in fungal propagation. By classifying spores based on origin, function, and organism, scientists and practitioners can harness their unique properties for innovation and problem-solving.

Spore Syringe Shelf Life: Room Temperature Storage Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Spore Function: Role in reproduction, survival, and dispersal across harsh environments

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. These microscopic structures, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are not just passive particles but active agents of persistence and propagation. Their primary function is to ensure the continuity of species across time and space, particularly in environments where survival is a constant challenge. Whether buried in soil, suspended in air, or adrift in water, spores remain dormant, biding their time until conditions are favorable for growth. This resilience is not merely a biological curiosity but a critical mechanism that has shaped ecosystems for millions of years.

Consider the reproductive strategy of ferns, which rely on spores to colonize new territories. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants, spores are haploid cells that develop into gametophytes, the sexual phase of the fern life cycle. This two-step process allows ferns to thrive in diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. For instance, a single fern frond can release thousands of spores, each capable of traveling miles on air currents. This dispersal mechanism ensures genetic diversity and increases the likelihood of successful colonization, even in fragmented or inhospitable landscapes.

Survival in harsh environments demands more than just dispersal—it requires resistance to extreme conditions. Bacterial endospores, such as those formed by *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax), can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C, radiation exposure, and desiccation for decades. This durability is achieved through a multi-layered protective coat and a dehydrated core, reducing metabolic activity to near zero. In practical terms, this means that sterilizing equipment in medical or laboratory settings requires autoclaving at 121°C for at least 15 minutes to ensure spore destruction. Such adaptations highlight the spore’s role as a biological fortress, safeguarding genetic material until conditions permit revival.

Dispersal strategies of spores are as varied as the organisms that produce them. Fungal spores, for example, are often ejected with explosive force, reaching velocities of up to 25 meters per second. This mechanism, observed in species like *Schizophyllum commune*, maximizes distance traveled and minimizes clustering, reducing competition among offspring. In contrast, plant spores, such as those of mosses, rely on wind or water for transport, often adhering to surfaces via sticky coatings or filamentous structures. These methods, while less dramatic, are equally effective in ensuring widespread distribution. Understanding these dispersal tactics is crucial for fields like agriculture, where spore-borne pathogens like *Puccinia graminis* (wheat rust) can devastate crops if left unchecked.

The spore’s role in biology is a testament to the ingenuity of evolution, blending simplicity with sophistication. From reproduction to survival and dispersal, spores are not just passive bystanders but active participants in the struggle for existence. Their ability to endure and propagate in the face of adversity offers lessons for biotechnology, conservation, and even space exploration. By studying spores, we gain insights into life’s tenacity and the strategies that enable it to flourish in even the most unforgiving environments.

Effective Milky Spore Powder Application: A Guide to Grub Control

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Structure: Protective layers, genetic material, and adaptations for longevity and resistance

Spores are nature’s time capsules, engineered for survival in the harshest conditions. At their core lies a protective fortress, a multilayered structure designed to shield genetic material from desiccation, radiation, and predators. The outermost layer, often called the exosporium, acts as a barrier against mechanical damage and environmental toxins. Beneath it, the spore coat provides additional protection, composed of proteins and polymers that resist heat, chemicals, and enzymes. In some species, like *Bacillus subtilis*, this coat is so resilient it can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C. These layers are not just passive shields; they are active participants in spore dormancy, regulating germination when conditions improve.

Encased within these protective layers is the spore’s genetic material, a compact and stabilized nucleus or DNA core. Unlike vegetative cells, spores minimize metabolic activity to conserve energy, ensuring their genetic integrity remains intact for decades or even centuries. For instance, bacterial endospores maintain their DNA in a dehydrated, crystalline state, reducing the risk of mutation. This genetic preservation is critical for long-term survival, allowing spores to persist in soil, water, and air until favorable conditions trigger germination. The efficiency of this system is evident in Antarctic lake sediments, where viable spores have been revived after being dormant for over 10,000 years.

Adaptations for longevity and resistance extend beyond physical structure. Spores exploit environmental cues to remain dormant, a strategy that maximizes their chances of survival. For example, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* produce melanin, a pigment that absorbs UV radiation and protects against DNA damage. Similarly, bacterial spores produce dipicolinic acid, a molecule that binds calcium ions and stabilizes the spore’s internal environment, further enhancing resistance to heat and chemicals. These biochemical adaptations complement the physical layers, creating a robust system that ensures spores can endure extreme conditions.

To harness spore resilience in practical applications, consider their role in biotechnology and agriculture. Spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used as biopesticides, their protective layers ensuring longevity on crops while their genetic material remains poised to produce toxins lethal to pests. In medicine, spore-forming probiotics like *Bacillus coagulans* survive stomach acids to deliver beneficial bacteria to the gut. For home gardeners, understanding spore structure can improve seed storage—keeping fungal spores in cool, dry conditions mimics their natural dormant state, extending viability. Whether in labs or gardens, spore structure is a blueprint for survival, offering lessons in protection and persistence.

Understanding Mould Spores: How They Spread and Thrive in Your Home

You may want to see also

Spore Germination: Conditions and mechanisms triggering spore activation and growth resumption

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, remain dormant until conditions favor growth. Spore germination, the process of reactivating these dormant cells, is a tightly regulated mechanism triggered by specific environmental cues. Understanding these conditions and mechanisms is crucial for fields like agriculture, medicine, and food preservation.

For successful germination, spores require a combination of factors. Water availability is paramount, as it rehydrates the spore and reactivates metabolic processes. Optimal temperature ranges, varying by species, provide the necessary energy for enzymatic activity. Nutrient availability, particularly carbon and nitrogen sources, signals a hospitable environment for growth. Notably, some spores require specific triggers, such as heat shock or exposure to certain chemicals, to break dormancy.

The germination process itself involves a series of intricate cellular events. Upon sensing favorable conditions, spores activate enzymes that degrade the protective spore coat, allowing water and nutrients to enter. This triggers the resumption of metabolic activity, including DNA repair and protein synthesis. The spore then emerges from its dormant state, initiating vegetative growth.

In practical applications, controlling spore germination is essential. In agriculture, understanding germination conditions helps optimize seed treatment and soil preparation. In food preservation, preventing spore germination through methods like pasteurization and irradiation ensures food safety. Conversely, in biotechnology, inducing spore germination is crucial for cultivating beneficial microorganisms.

Interestingly, some spores exhibit a phenomenon called "superdormancy," requiring prolonged exposure to specific conditions before germinating. This mechanism further enhances their survival capabilities in harsh environments. Studying these mechanisms not only deepens our understanding of microbial life but also opens avenues for developing novel strategies for spore control, with implications for both beneficial and harmful applications.

Are Spores on Potatoes Safe to Eat? A Complete Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore is a reproductive structure produced by certain organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and plants, that is capable of developing into a new individual under favorable conditions. Spores are typically resistant to harsh environments and can remain dormant for extended periods.

Spores are unicellular and are produced by sporophytes in plants through asexual reproduction (sporulation), while seeds are multicellular structures produced by angiosperms and gymnosperms through sexual reproduction. Seeds contain an embryo and stored food, whereas spores do not.

In fungi, spores play a crucial role in reproduction and dispersal. They are produced by specialized structures like sporangia or asci and can be dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Once spores land in a suitable environment, they germinate and grow into new fungal individuals.