Spores play a crucial role in the life cycles of various organisms, particularly fungi, plants, and some bacteria, serving as highly resilient reproductive or dispersal units. These microscopic structures are designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and lack of nutrients, ensuring the survival of the species during unfavorable periods. In fungi, spores are the primary means of reproduction and dispersal, allowing them to colonize new habitats efficiently. For plants like ferns and mosses, spores are essential for asexual reproduction and the alternation of generations. Additionally, bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Bacillus* species, enable long-term survival in adverse environments. Overall, spores are a vital adaptation that enhances the persistence and spread of organisms across diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival Mechanism | Spores are highly resistant structures that enable organisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, plants) to survive harsh environmental conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and radiation. |

| Dormancy | Spores remain dormant for extended periods, sometimes for years or even centuries, until favorable conditions return for growth and reproduction. |

| Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing species to colonize new habitats and expand their geographic range. |

| Reproduction | Spores serve as reproductive units, capable of developing into new individuals without fertilization (in some cases) or after germination under suitable conditions. |

| Genetic Diversity | Spores can undergo genetic recombination during formation, increasing genetic diversity and adaptability within populations. |

| Resistance to Stress | Spores have thick, protective walls composed of materials like sporopollenin (in plants) or dipicolinic acid (in bacteria), providing resistance to desiccation, chemicals, and UV radiation. |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a crucial role in ecosystems by ensuring the continuity of species, contributing to nutrient cycling, and serving as food sources for certain organisms. |

| Medical and Industrial Applications | Bacterial spores (e.g., Bacillus anthracis) are studied for their role in diseases, while others are used in biotechnology for enzyme production or as probiotics. |

| Size and Shape | Spores vary in size and shape depending on the species, ranging from microscopic bacterial endospores to larger fungal spores visible under magnification. |

| Germination | Spores germinate when environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, temperature, nutrients) become favorable, resuming metabolic activity and growth. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Reproduction: Spores enable asexual reproduction, ensuring survival and dispersal in fungi and plants

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions like drought, heat, and cold, preserving genetic material

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal, expanding species' geographic reach

- Ecological Roles: Spores contribute to nutrient cycling and ecosystem balance in various environments

- Human Applications: Spores are used in agriculture, biotechnology, and food production (e.g., mushrooms)

Spores in Reproduction: Spores enable asexual reproduction, ensuring survival and dispersal in fungi and plants

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, enabling fungi and plants to reproduce asexually in environments where traditional methods falter. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to germinate, spores are lightweight, resilient, and capable of remaining dormant for years until conditions are favorable. This adaptability ensures the continuity of species across harsh climates, from arid deserts to nutrient-poor soils. For instance, fungal spores can travel vast distances on air currents, colonizing new habitats with minimal energy expenditure. This efficiency in dispersal and survival underscores their role as a biological insurance policy.

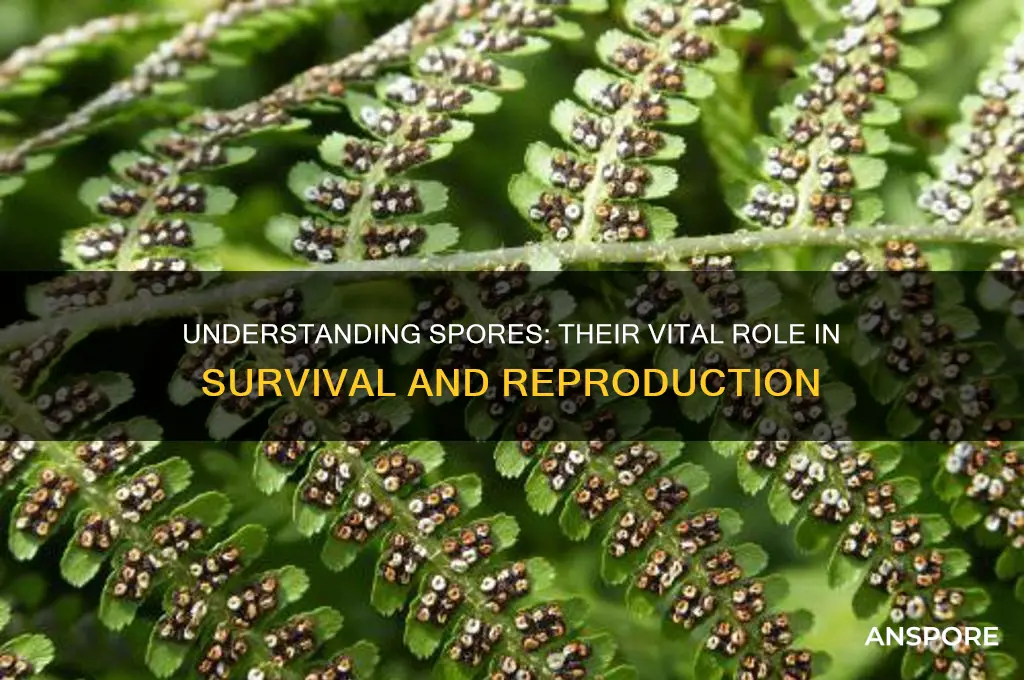

Consider the life cycle of ferns, a prime example of spore-driven reproduction in plants. Ferns produce tiny, dust-like spores on the undersides of their fronds. When released, these spores can land in diverse environments, germinating into small, heart-shaped gametophytes. These gametophytes then produce eggs and sperm, which, upon fertilization, grow into new fern plants. This two-stage life cycle—alternating between spore-producing and gamete-producing generations—highlights the spore’s dual role: as a reproductive unit and a dispersal mechanism. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring high humidity and indirect light mimics the spore’s natural habitat, increasing the likelihood of successful germination.

Fungi, too, rely heavily on spores for survival and propagation. Take the common mold *Penicillium*, which produces spores in chains called conidia. These spores are not only resistant to desiccation and temperature extremes but also serve as a means of rapid colonization. In a laboratory setting, fungal spores are often cultured on agar plates at temperatures between 22°C and 28°C, demonstrating their ability to thrive under controlled conditions. This resilience makes them invaluable in biotechnology, where spores are used to produce antibiotics like penicillin. However, their tenacity also poses challenges, as fungal spores can contaminate food and cause allergies in humans.

The comparative advantage of spores lies in their simplicity and efficiency. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires two parents and favorable mating conditions, spore production is a solitary process. A single organism can generate thousands of spores, each genetically identical to the parent. This clonality ensures consistency in traits beneficial for survival, such as toxin resistance in certain fungi. However, it also limits genetic diversity, making populations vulnerable to sudden environmental changes. For conservationists, understanding this trade-off is crucial when managing ecosystems dominated by spore-reproducing species.

In practical terms, harnessing the power of spores can benefit agriculture and horticulture. For example, mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, can be introduced to crops via spore inoculants. These spores enhance nutrient uptake and drought resistance, improving yields without chemical fertilizers. Gardeners can create spore prints by placing mushroom caps gill-side down on paper overnight, capturing spores for identification or cultivation. Such techniques not only deepen our appreciation for spores but also empower us to utilize them sustainably, bridging the gap between nature’s ingenuity and human innovation.

Mastering Mushroom Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions like drought, heat, and cold, preserving genetic material

Spores are nature's time capsules, engineered to endure environments that would annihilate most life forms. Consider the desert, where temperatures soar above 50°C (122°F) and rainfall is a rarity. Here, bacterial endospores can remain dormant for centuries, their metabolic activity reduced to near-zero. Similarly, in the Arctic permafrost, fungal spores have been revived after being frozen for over 10,000 years. This resilience is not random but a product of evolutionary precision: spores shed water, harden their cell walls, and minimize chemical reactions that could degrade their DNA. Their ability to withstand such extremes ensures that genetic material persists, ready to reactivate when conditions improve.

To understand how spores achieve this, imagine a survivalist preparing for a decade in isolation. They would dehydrate food, fortify their shelter, and minimize energy use—sporulation follows a similar strategy. When a bacterium forms an endospore, it expels most of its water, concentrating its DNA and essential proteins into a protective shell. This shell, composed of layers like the exosporium and spore coat, acts as a barrier against heat, radiation, and desiccation. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can survive temperatures up to 120°C (248°F) for hours, thanks to their calcium-dipicolinic acid complex, which stabilizes the spore’s structure. This metabolic shutdown is so effective that spores can remain viable in environments where no active life could survive.

The practical implications of spore survival mechanisms extend beyond biology into fields like agriculture and space exploration. Farmers use spore-forming bacteria, such as *Clostridium pasteurianum*, to fix nitrogen in soil, even in drought-prone regions. In space, NASA studies spores to understand how life might endure interstellar travel or exist on Mars, where temperatures drop to -80°C (-112°F) and radiation is intense. For hobbyists or researchers culturing microorganisms, storing spores at -20°C (-4°F) in a glycerol solution ensures long-term viability, while avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles prevents DNA damage. These applications highlight how spore resilience is not just a biological curiosity but a tool for innovation.

Comparing spores to seeds reveals both parallels and contrasts in survival strategies. While seeds rely on external protection (e.g., thick coats or chemical inhibitors) and internal reserves (e.g., starch), spores achieve longevity through extreme metabolic reduction and structural fortification. A seed might last decades, but a spore can outlast it by millennia. However, spores’ success comes at a cost: they cannot grow or reproduce until conditions are ideal, whereas seeds can germinate in suboptimal environments. This trade-off underscores the spore’s role as a last-resort mechanism, optimized for survival over immediacy.

In essence, spores are the ultimate survivalists, preserving life’s blueprint in the face of adversity. Their ability to withstand drought, heat, and cold is not just a biological marvel but a lesson in adaptability. Whether you’re a scientist studying extremophiles or a gardener saving seeds, understanding spore mechanisms offers insights into resilience—both in nature and in practice. By mimicking their strategies, we can protect genetic diversity, engineer hardier crops, and even envision life beyond Earth. Spores remind us that survival is not about enduring the present but safeguarding the future.

The Last of Us: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in the Show

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal, expanding species' geographic reach

Spores, those microscopic marvels of survival, rely heavily on external forces to travel beyond their origin. Wind, water, and animals emerge as the unsung heroes in this journey, each playing a distinct role in dispersing spores across vast distances. Wind, the most ubiquitous agent, carries lightweight spores aloft, sometimes for thousands of miles, enabling species to colonize new habitats far from their source. For instance, fungal spores like those of *Puccinia graminis* (the cause of wheat rust) can traverse continents, posing both ecological and agricultural challenges. This method is particularly effective for species that produce spores in large quantities, ensuring at least a few land in favorable environments.

Water, though less immediate in its reach, offers a reliable pathway for spore dispersal, especially in aquatic and semi-aquatic ecosystems. Spores of algae, ferns, and certain fungi are often buoyant, allowing them to drift along currents until they settle in suitable substrates. For example, the spores of *Azolla*, a water fern, can disperse across ponds and slow-moving streams, forming dense mats that provide habitat and food for aquatic life. This method is particularly advantageous in environments where wind dispersal is less effective, such as dense forests or shaded areas.

Animals, both large and small, act as unwitting couriers for spores, carrying them on their fur, feathers, or even digestive tracts. Zoospores, a specialized type of spore, can actively swim to new locations, but many rely on hitchhiking. Birds and mammals, for instance, may pick up spores while foraging and deposit them in distant locations through their droppings or grooming behaviors. A notable example is the dispersal of orchid seeds, which often adhere to the bodies of insects or birds, ensuring the plants colonize diverse habitats. This symbiotic relationship highlights how animals inadvertently contribute to the survival and expansion of spore-producing species.

Each dispersal method comes with its own set of advantages and limitations. Wind maximizes reach but lacks precision, while water offers consistency in aquatic environments but is confined to specific ecosystems. Animal dispersal, though localized, benefits from targeted placement in nutrient-rich areas. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for conservation efforts, agricultural management, and even controlling invasive species. For gardeners, leveraging these methods can enhance plant diversity—for example, placing spore-bearing plants near water sources or in windy areas to encourage natural dispersal.

In practical terms, harnessing these dispersal methods can be a game-changer for ecological restoration projects. By strategically planting spore-producing species in areas prone to wind or water flow, or by introducing animals known to carry spores, conservationists can accelerate habitat recovery. For instance, reintroducing beavers, whose dams create slow-moving water ideal for spore dispersal, can revitalize wetland ecosystems. Similarly, farmers can reduce the risk of fungal diseases by monitoring wind patterns and adjusting planting schedules to minimize spore exposure during vulnerable crop stages. Mastery of these dispersal methods transforms spores from passive travelers into active agents of ecological change.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Growing Spores from Syringe Step-by-Step

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ecological Roles: Spores contribute to nutrient cycling and ecosystem balance in various environments

Spores, often microscopic and resilient, play a pivotal role in maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems across the globe. These dormant, reproductive units are not merely survival mechanisms for fungi, plants, and certain bacteria; they are active contributors to nutrient cycling, a fundamental process that sustains life. In forests, for instance, fungal spores decompose organic matter, breaking down complex compounds into simpler nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. This process enriches the soil, fostering plant growth and ensuring the continuity of the food chain. Without spores, this cycle would falter, leading to nutrient depletion and ecosystem collapse.

Consider the instructive example of mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Their spores disperse widely, colonizing new areas and enhancing nutrient uptake for host plants. In agricultural systems, this relationship can reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers by up to 30%, according to studies. Farmers can encourage this natural process by incorporating spore-rich compost into soil, particularly in organic farming practices. However, caution must be exercised to avoid over-application, as excessive spores can disrupt microbial balance and lead to unintended consequences like soil acidity.

From a persuasive standpoint, spores are unsung heroes of ecological resilience. In disturbed environments, such as post-wildfire landscapes, spores of pioneer species like lichens and mosses are often the first to colonize barren soil. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions and rapidly establish themselves kickstarts the recovery process, preventing erosion and preparing the ground for more complex vegetation. Conservation efforts should prioritize protecting spore-producing organisms, as their loss could hinder ecosystem recovery and exacerbate the impacts of climate change.

Comparatively, the role of spores in aquatic ecosystems highlights their versatility. In wetlands and freshwater systems, algal spores contribute to nutrient cycling by fixing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen during photosynthesis. This process not only supports aquatic life but also mitigates greenhouse gas levels. Unlike terrestrial spores, which often rely on wind or animals for dispersal, aquatic spores use water currents, ensuring widespread distribution. This difference underscores the adaptability of spores to diverse environments, making them indispensable across ecosystems.

In conclusion, spores are not just passive agents of reproduction but dynamic contributors to ecological stability. Their involvement in nutrient cycling ensures the health and productivity of ecosystems, from dense forests to tranquil wetlands. By understanding and supporting their roles, we can foster more sustainable practices in agriculture, conservation, and environmental restoration. Whether through mindful land management or protective policies, recognizing the value of spores is essential for maintaining the balance of our planet’s ecosystems.

Discover the Best Platforms to Play Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Human Applications: Spores are used in agriculture, biotechnology, and food production (e.g., mushrooms)

Spores, often microscopic and resilient, serve as nature’s survival capsules, but their utility extends far beyond ecological roles. In agriculture, spores of beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* are applied as biofertilizers to enhance soil health and plant growth. These spores colonize roots, promoting nutrient uptake and protecting crops from pathogens. For instance, a single gram of *Trichoderma* spores can treat up to 10 square meters of soil, making it a cost-effective solution for sustainable farming. Farmers often mix spore-based inoculants with water and apply them directly to seeds or soil, ensuring robust plant development without chemical dependency.

In biotechnology, spores are harnessed for their ability to produce enzymes and bioactive compounds. For example, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores are engineered to secrete proteins toxic to pests but harmless to humans, forming the basis of biopesticides. These spore-derived products are widely used in organic farming, reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals. Similarly, mushroom mycelium, grown from spores, is being explored as a sustainable material for packaging and textiles, offering biodegradable alternatives to plastic. This dual role of spores—as both producers and products—highlights their versatility in biotechnological innovation.

Food production, particularly mushroom cultivation, relies heavily on spores as the starting point for growth. Oyster, shiitake, and button mushrooms begin as spores inoculated into substrates like straw or sawdust. A single spore can develop into a mycelium network that eventually fruits into edible mushrooms, yielding up to 1 kilogram of produce per 10 kilograms of substrate. Home growers often use spore syringes or spawn bags to initiate cultivation, ensuring a consistent and high-quality harvest. Beyond mushrooms, spore-fermented foods like tempeh and certain cheeses showcase how spores contribute to both nutrition and flavor.

Comparatively, spore applications in these fields differ in scale and methodology but share a common goal: leveraging nature’s efficiency. While agriculture focuses on soil and plant health, biotechnology emphasizes industrial and environmental solutions, and food production prioritizes yield and quality. Each application requires precise conditions—temperature, humidity, and substrate composition—to activate spores effectively. For instance, mushroom spores germinate optimally at 22–25°C, while *Trichoderma* spores thrive in slightly warmer soils. Understanding these nuances ensures successful implementation across sectors.

In conclusion, spores are not just biological curiosities but practical tools with transformative potential. From enriching soils to creating sustainable materials and nourishing food, their applications are as diverse as they are impactful. By mastering spore cultivation and deployment, humans can address pressing challenges in agriculture, biotechnology, and food production, paving the way for a more resilient and sustainable future. Whether you’re a farmer, scientist, or home grower, spores offer a wealth of opportunities waiting to be explored.

Understanding Plant Spores: Tiny Survival Units and Their Role in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary role of spores is to serve as a reproductive and survival mechanism for organisms, particularly in fungi, plants (like ferns and mosses), and some bacteria. They allow these organisms to disperse, survive harsh conditions, and reproduce asexually.

Spores are highly resistant structures that can withstand extreme conditions such as drought, heat, cold, and lack of nutrients. This dormancy enables organisms to survive until conditions become favorable for growth and reproduction.

Spores are typically single-celled and produced by asexual or sexual reproduction in non-seed plants (like ferns and mosses), while seeds are multicellular structures produced by flowering plants and gymnosperms, containing an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat.

Spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or hairs, allowing them to be carried by wind, water, or animals over long distances. This dispersal mechanism helps organisms colonize new habitats and expand their range.

While spores are most commonly associated with plants (like ferns and mosses) and fungi, certain bacteria (e.g., endospores in Bacillus and Clostridium) and some protozoa also produce spore-like structures for survival and dispersal.