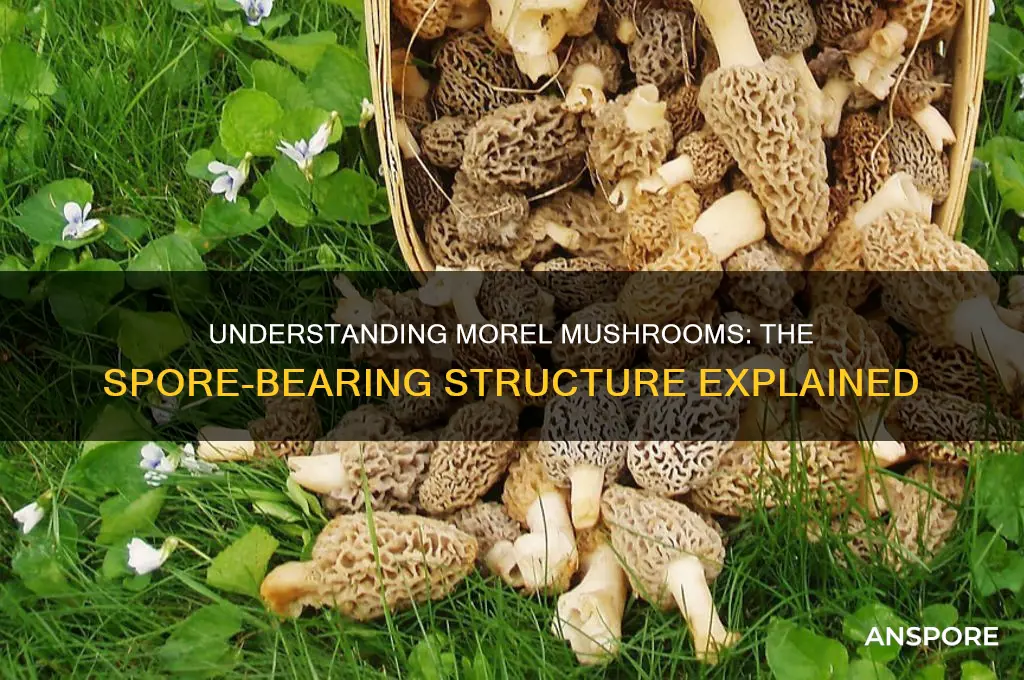

Morel mushrooms, prized for their unique flavor and texture, are a delicacy in the culinary world. A key aspect of their biology lies in their reproductive structure: the spore-bearing part. In morels, this is known as the ascocarp, a fruiting body that houses numerous asci (microscopic, sac-like structures). Each ascus contains spores, which are dispersed to propagate the fungus. The ascocarp in morels is characterized by its honeycomb-like, spongy appearance, formed by a network of ridges and pits. This distinctive structure not only aids in spore dispersal but also makes morels easily identifiable in the wild. Understanding the spore-bearing part of a morel is essential for both foragers and mycologists, as it highlights the mushroom's life cycle and ecological role.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Structure | The spore-bearing part of a morel mushroom is the cap (also called the pileus). |

| Shape | Conical or oval with a honeycomb-like appearance due to ridges and pits (alveoli). |

| Color | Varies from yellow, tan, brown, to gray depending on species. |

| Texture | Spongy and porous due to the network of ridges and pits. |

| Spore Production | Spores are produced on the inner surfaces of the ridges and pits. |

| Spore Type | Ascospores (produced within sac-like structures called asci). |

| Spore Color | Typically cream to yellow in mass. |

| Function | Disperses spores for reproduction. |

| Scientific Term | The spore-bearing structure is technically called a hymenium, which lines the ridges and pits of the cap. |

Explore related products

$16.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Structure: Spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by morel mushrooms for propagation

- Ascus Formation: Spores develop inside sac-like structures called asci, which are housed in the morel's cap

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released through the morel's honeycomb-like pits, aided by wind and water

- Role in Reproduction: Spores germinate under ideal conditions, growing into new mycelium networks to form mushrooms

- Identification Feature: The spore-bearing tissue, or hymenium, lines the morel's ridges and pits, aiding identification

Spore Structure: Spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by morel mushrooms for propagation

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers and chefs alike, rely on a sophisticated yet microscopic mechanism for reproduction: spores. These single-celled units, produced in vast quantities, are the lifeblood of the morel’s propagation strategy. Encased within the honeycomb-like cap of the mushroom, the spores are not merely passive agents but highly specialized structures designed for dispersal and survival. Each spore is a self-contained genetic package, capable of developing into a new mycelium under the right conditions. Understanding their structure is key to appreciating the morel’s ecological role and the challenges of cultivating these elusive fungi.

Analyzing the spore structure reveals a marvel of natural engineering. Morel spores are typically elliptical and measure between 15–25 micrometers in length, making them invisible to the naked eye. Their walls are composed of chitin, a durable material that protects the genetic material within from environmental stressors such as desiccation, UV radiation, and predation. This resilience is critical, as spores must endure harsh conditions during dispersal—often carried by wind or water—before finding a suitable substrate to germinate. The surface of the spore may also feature ridges or bumps, which aid in adhesion to surfaces and increase the likelihood of successful colonization.

For the aspiring mycologist or forager, understanding spore structure has practical implications. Spores are released from the mushroom’s cap through tiny openings called asci, which act as miniature launchpads. To collect spores for study or cultivation, one can place a mature morel cap on a piece of paper or glass slide, allowing the spores to fall naturally. This method, known as spore printing, not only aids in identification but also provides material for inoculating substrate in controlled environments. However, caution is advised: while morel spores are not toxic, inhaling them can irritate the respiratory system, so working in a well-ventilated area is essential.

Comparatively, morel spores differ from those of other fungi in their size, shape, and dispersal mechanisms. Unlike the powdery spores of molds or the gill-released spores of agarics, morel spores are larger and more robust, reflecting their need to survive in diverse habitats. This uniqueness also complicates cultivation efforts, as morels have specific symbiotic relationships with soil bacteria and trees, making it difficult to replicate their growth conditions artificially. Despite these challenges, advancements in mycorrhizal research offer hope for future cultivation techniques, underscoring the importance of studying spore structure in unlocking the morel’s secrets.

In conclusion, the spore structure of morel mushrooms is a testament to nature’s ingenuity, blending durability, efficiency, and adaptability. From their chitinous walls to their precise dispersal mechanisms, spores are the cornerstone of the morel’s lifecycle. Whether you’re a forager, chef, or scientist, understanding these microscopic units deepens your appreciation for these enigmatic fungi and their role in ecosystems. By studying spores, we not only gain insights into morel biology but also pave the way for sustainable cultivation practices that could one day make these delicacies more accessible to all.

Harvesting Mushrooms: Can You Get a Second Flush?

You may want to see also

Ascus Formation: Spores develop inside sac-like structures called asci, which are housed in the morel's cap

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers and chefs alike, owe their reproductive success to a fascinating microscopic process: ascus formation. Within the honeycomb-like cap of a morel lies a network of sac-like structures called asci, each a cradle for developing spores. This intricate system is the heart of the morel's spore-bearing mechanism, a marvel of fungal biology that ensures the species' propagation.

Imagine a tiny, elongated sac, its walls thin yet resilient, filled with a cluster of spores. This is the ascus, a structure unique to the Ascomycota phylum, to which morels belong. As the morel matures, these asci swell with genetic potential, each containing eight spores arranged in a linear fashion. The asci are not solitary; they are embedded within the flesh of the morel's cap, protected yet poised for dispersal. When conditions are right—often triggered by environmental cues like moisture and temperature—the asci undergo a dramatic transformation. Their tips, known as opercula, rupture, releasing the spores into the air. This process, called deliquescence, is both precise and explosive, ensuring that spores are scattered widely to colonize new habitats.

Understanding ascus formation is crucial for foragers and cultivators alike. Foraging at the right time, typically in spring when morels are mature but before spore release, maximizes yield and quality. Cultivators, on the other hand, can mimic environmental triggers to optimize spore production in controlled settings. For instance, maintaining humidity levels between 80-90% and temperatures around 60-70°F (15-21°C) can encourage ascus development. However, caution is necessary: overripe morels, with asci that have already discharged spores, may have a mealy texture and reduced culinary appeal.

The ascus formation process also highlights the morel's ecological role. Spores released from asci can travel significant distances, carried by wind or water, to colonize new substrates. This adaptability is key to the morel's survival in diverse environments, from forest floors to disturbed soils. For enthusiasts, observing asci under a microscope reveals their beauty and complexity, offering a deeper appreciation for these enigmatic fungi. Whether you're a forager, chef, or mycologist, understanding ascus formation transforms the morel from a culinary delight into a window into the intricate world of fungal reproduction.

Ragu Mushroom Sauce: Allergen-Free and Delicious

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are released through the morel's honeycomb-like pits, aided by wind and water

Morels, with their distinctive honeycomb-like pits, are not just a forager’s treasure but also a marvel of natural engineering. These pits, technically called alveoli, serve as the spore-bearing structures of the mushroom. Unlike the gills of common mushrooms, morels release spores through these tiny, honeycomb-shaped chambers. This design is both functional and efficient, maximizing surface area for spore dispersal while maintaining structural integrity. Understanding this mechanism is key to appreciating how morels propagate and thrive in their environments.

The dispersal of morel spores is a delicate interplay of biology and physics. When mature, the spores are released from the alveoli, often triggered by environmental factors like humidity changes. Wind plays a primary role in carrying these lightweight spores over distances, ensuring genetic diversity across populations. Water, too, aids in dispersal, particularly in damp environments where spores can adhere to droplets and be transported to new locations. This dual mechanism highlights the adaptability of morels, allowing them to colonize diverse habitats, from forest floors to riverbanks.

Foraging enthusiasts and mycologists alike can observe this process in action by examining mature morels in their natural habitat. Gently shaking a morel over a white surface will reveal a fine dusting of spores, demonstrating their readiness for dispersal. However, caution is advised: harvesting morels before they release spores can disrupt their reproductive cycle. To support their propagation, leave some mature specimens undisturbed, ensuring future generations of these prized fungi.

Comparatively, morels’ spore dispersal mechanism contrasts with other mushrooms, such as puffballs, which rely on sudden bursts of air to release spores. The gradual, wind- and water-aided release of morel spores reflects their evolutionary strategy, favoring persistence over spectacle. This approach aligns with their role as decomposers, breaking down organic matter in forest ecosystems while ensuring their own survival through widespread spore distribution.

In practical terms, understanding morel spore dispersal can enhance cultivation efforts. Recreating natural conditions—such as maintaining humidity levels and providing airflow—can encourage spore release in controlled environments. For home growers, placing mature morels in a well-ventilated, damp space can mimic their native habitat, increasing the likelihood of successful spore germination. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, the honeycomb-like pits of morels are not just a defining feature but a testament to their ingenious dispersal mechanisms.

Mushrooms: A Fiber-Rich Superfood?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role in Reproduction: Spores germinate under ideal conditions, growing into new mycelium networks to form mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, with their distinctive honeycomb caps, are not just a forager's delight but also a marvel of fungal reproduction. The spore-bearing part of a morel, known as the ascocarp, is a complex structure designed to disperse spores efficiently. These spores are the key to the mushroom's life cycle, acting as the seeds of the fungal world. When conditions are just right—adequate moisture, temperature, and organic matter—these spores germinate, initiating a process that is both intricate and vital for the species' survival.

The germination of morel spores is a delicate dance with nature. Each spore, microscopic in size, contains the genetic material necessary to develop into a new mycelium network. This network, a web of thread-like hyphae, spreads through the soil, absorbing nutrients and preparing the groundwork for future mushroom growth. The process is highly dependent on environmental cues: too dry, and the spores remain dormant; too wet, and they may rot. Ideal conditions typically include a soil temperature between 50°F and 60°F (10°C and 15°C) and a pH level around 6.0 to 7.0. Foraging enthusiasts and cultivators alike must mimic these conditions to encourage spore germination, often using techniques like cold stratification to simulate winter conditions, which morels naturally require.

Once germinated, the mycelium network expands, forming a symbiotic relationship with the surrounding environment. This network can persist for years, lying dormant until conditions are favorable for fruiting. When the time is right, the mycelium aggregates resources to form the ascocarp, the spore-bearing structure we recognize as the morel mushroom. This fruiting process is not just a biological necessity but also a culinary opportunity, as it produces the prized mushroom caps sought after by chefs and foragers. Understanding this cycle allows cultivators to optimize conditions, increasing the likelihood of a successful harvest.

The role of spores in morel reproduction highlights the resilience and adaptability of fungi. Unlike plants, which rely on seeds and roots, morels depend on spores and mycelium to propagate. This distinction makes their cultivation both challenging and rewarding. For those attempting to grow morels, patience is key. Spores can take several years to develop into mature mushrooms, and even then, success is not guaranteed. Practical tips include using well-draining soil, incorporating organic matter like wood chips, and maintaining consistent moisture levels. By respecting the natural processes of spore germination and mycelium growth, cultivators can increase their chances of nurturing these elusive fungi.

In essence, the spore-bearing part of a morel mushroom is not just a structure but a gateway to new life. From spore to mycelium to mushroom, each stage is a testament to the fungus's ability to thrive in specific conditions. For foragers, understanding this cycle deepens their appreciation for the find; for cultivators, it provides a roadmap to success. Whether in the wild or in a controlled environment, the role of spores in morel reproduction remains a fascinating and essential process, bridging the gap between biology and culinary delight.

Tearing Oyster Mushrooms: The Right Way

You may want to see also

Identification Feature: The spore-bearing tissue, or hymenium, lines the morel's ridges and pits, aiding identification

The intricate honeycomb-like structure of a morel mushroom is more than just a visual marvel; it’s a key to its identity. Unlike most mushrooms, where the spore-bearing tissue (hymenium) is found on gills or pores, morels house this critical layer within their ridges and pits. This unique arrangement is a defining feature for foragers, distinguishing morels from look-alikes like false morels, which often have smoother, brain-like folds lacking a true hymenium.

To identify a morel confidently, inspect its cap closely. The hymenium should line the interior ridges and pits, creating a spongy, honeycomb appearance. Use a magnifying lens if necessary—the tissue will appear as a fine, granular layer. False morels, in contrast, often have a solid or chambered interior without this distinct lining. This detail is crucial, as misidentification can lead to toxic consequences.

Foraging tip: Always cut a morel in half lengthwise to verify the hymenium’s presence. A true morel will reveal a hollow stem and a cap with ridges and pits fully lined with spore-bearing tissue. If the interior is solid, compartmentalized, or lacks this lining, discard it immediately. This simple step can prevent accidental poisoning and ensure a safe harvest.

Comparatively, the hymenium’s placement in morels is an evolutionary adaptation, maximizing spore dispersal through their exposed ridges. This contrasts with gilled mushrooms, which release spores from the underside of caps. Understanding this biology not only aids identification but also deepens appreciation for morels’ ecological role as decomposers and their culinary value.

In conclusion, the hymenium’s location within a morel’s ridges and pits is both an identification tool and a testament to its unique biology. By focusing on this feature, foragers can confidently distinguish morels from dangerous mimics, ensuring a safe and rewarding harvest. Always prioritize verification—a small effort with significant payoff.

Jazz Up Your Spinach Mushroom Pizza with These Flavorful Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The spore-bearing part of a morel mushroom is the cap, specifically the ridges and pits (or honeycomb-like structure) on its surface, which contain the asci that produce and release spores.

Morel mushrooms release their spores through tiny, sac-like structures called asci, located within the pits and ridges of the cap. As the asci mature, they forcibly eject the spores into the air.

No, the spores of a morel mushroom are microscopic and not visible to the naked eye. They are typically observed under a microscope or identified by their dispersal patterns.