Wisconsin is home to a diverse array of mushrooms, many of which are not only fascinating to observe but also safe and delicious to eat. Foraging for edible mushrooms in Wisconsin can be a rewarding activity, but it requires knowledge and caution, as some species closely resemble their toxic counterparts. Common edible mushrooms found in the state include the Chanterelle, known for its fruity aroma and golden color; the Morel, a highly prized spring mushroom with a honeycomb-like cap; and the Chicken of the Woods, which grows in vibrant orange-yellow clusters on trees. However, it’s crucial to consult reliable field guides or experienced foragers to avoid dangerous species like the Amanita or Galerina. Always ensure proper identification before consuming any wild mushrooms to enjoy Wisconsin’s fungal bounty safely.

Explore related products

$12.98 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Morel mushrooms: highly prized, honeycomb-like caps, found in wooded areas

- Chanterelles: golden, trumpet-shaped, fruity aroma, grow near hardwoods

- Oyster mushrooms: fan-shaped, grow on trees, mild flavor, easy to identify

- Lion’s Mane: shaggy, white, seafood-like texture, found on dead trees

- Chicken of the Woods: bright orange, shelf-like, grows on oak trees

Morel mushrooms: highly prized, honeycomb-like caps, found in wooded areas

Morel mushrooms, with their distinctive honeycomb-like caps, are a forager’s treasure in Wisconsin’s wooded areas. These fungi are highly prized for their earthy, nutty flavor and meaty texture, making them a culinary delicacy. Unlike many other mushrooms, morels are relatively easy to identify due to their unique appearance, which reduces the risk of mistaking them for toxic look-alikes. However, proper identification is still crucial, as false morels can be dangerous if consumed. Spring is the prime season for morel hunting, typically from April to June, when the soil temperature reaches around 50°F and moisture levels are high. Armed with a mesh bag for collecting and a keen eye, foragers can uncover these gems hiding at the base of trees or in areas with decaying wood.

To successfully hunt morels, focus on specific habitats. They thrive in wooded areas, particularly those with elm, ash, or aspen trees, which are common in Wisconsin. Burn sites from controlled forest fires are also prime locations, as the ash enriches the soil and promotes morel growth. When searching, look for areas with partial sunlight and well-drained soil. Morels often grow in clusters, so finding one usually means more are nearby. Patience is key, as their camouflage can make them difficult to spot. Once collected, clean the mushrooms by gently brushing off dirt and soaking them in cold water to remove debris from their spongy caps.

Preparing morels enhances their flavor and ensures safety. Always cook them thoroughly, as raw morels can cause digestive discomfort. A classic method is to sauté them in butter with garlic and thyme, allowing their earthy notes to shine. For a crispy texture, dip them in a batter of egg and flour before frying. Drying morels is an excellent way to preserve them for later use; simply slice them and dehydrate at a low temperature until brittle. Rehydrate dried morels by soaking them in warm water for 20 minutes before cooking. Pairing morels with rich ingredients like cream, cheese, or steak complements their robust flavor, making them a standout in any dish.

While morels are a forager’s dream, caution is essential. Always avoid consuming mushrooms unless you are 100% certain of their identification. False morels, which have a wrinkled or brain-like appearance instead of honeycomb caps, can cause severe illness. If in doubt, consult a field guide or an experienced forager. Additionally, be mindful of foraging regulations and respect private property. In Wisconsin, morel hunting is a cherished tradition, but sustainability is key—never overharvest, and leave some mushrooms to spore and ensure future growth. With proper knowledge and care, morels can be a rewarding and delicious part of your culinary adventures.

Exploring Washington's Mushrooms: Are They All Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Chanterelles: golden, trumpet-shaped, fruity aroma, grow near hardwoods

Chanterelles, with their golden hue and trumpet-like shape, are a forager’s treasure in Wisconsin’s hardwood forests. These mushrooms are not just visually striking but also emit a distinct fruity aroma that makes them easier to identify. Unlike many other fungi, chanterelles form symbiotic relationships with hardwood trees like oak, beech, and birch, so look for them near these species during late summer and fall. Their texture is meaty yet delicate, making them a chef’s favorite for sautéing, grilling, or adding to creamy sauces.

Identifying chanterelles requires attention to detail. Their false gills, which fork and wrinkle rather than being straight, are a key feature. The fruity scent, often compared to apricots or peaches, is another giveaway. However, caution is essential: false chanterelles, like the jack-o’lantern mushroom, resemble them but are toxic. Always verify by checking for the forked gills and absence of a sharp, unpleasant odor. If in doubt, consult a field guide or experienced forager.

Foraging for chanterelles is as much about patience as it is about location. They thrive in moist, well-drained soil under hardwood canopies, often hidden among leaves or moss. Carry a basket rather than a plastic bag to allow spores to disperse, ensuring future growth. Limit your harvest to a few pounds per site to sustain the ecosystem. Once collected, clean them gently with a brush or damp cloth to preserve their delicate structure.

In the kitchen, chanterelles shine with minimal preparation. Sauté them in butter with garlic and thyme to enhance their natural flavor, or dry them for year-round use. Their umami-rich profile pairs well with eggs, pasta, and risotto. For preservation, blanch them briefly before freezing to retain texture. Whether you’re a seasoned forager or a curious beginner, chanterelles offer a rewarding blend of adventure and culinary delight.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Edible Fungi at Home

You may want to see also

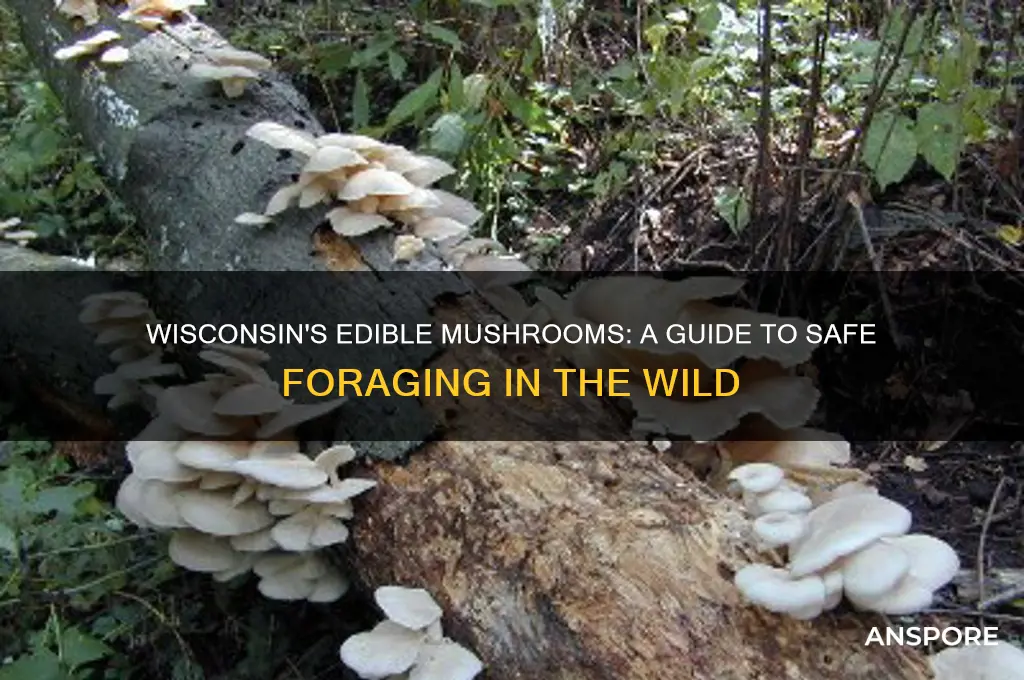

Oyster mushrooms: fan-shaped, grow on trees, mild flavor, easy to identify

Oyster mushrooms, with their distinctive fan-shaped caps, are a forager’s delight in Wisconsin’s forests. Unlike many fungi that hide in the underbrush, these mushrooms grow conspicuously on trees, often in clusters that resemble shelves. This habit makes them easy to spot, even for novice foragers. Their mild, slightly nutty flavor pairs well with a variety of dishes, from stir-fries to soups, making them a versatile addition to any kitchen.

Identifying oyster mushrooms is relatively straightforward, thanks to their unique characteristics. Look for their fan-like caps, which range in color from pale gray to brown, and their decurrent gills that run down the stem. They typically grow on hardwood trees, such as oak or beech, and are most abundant in the fall. However, caution is key: always double-check your find with a reliable guide or expert, as some toxic mushrooms can resemble oysters.

Foraging for oyster mushrooms in Wisconsin offers both culinary and ecological rewards. These fungi play a vital role in forest ecosystems by decomposing dead wood, returning nutrients to the soil. When harvesting, use a knife to cut the mushrooms at the base, leaving the rest of the organism intact to continue growing. Aim to collect no more than two-thirds of a cluster to ensure sustainability.

Cooking oyster mushrooms is simple yet transformative. Their delicate texture becomes pleasantly chewy when sautéed in butter or olive oil. For a quick dish, try tossing them with garlic, thyme, and a splash of lemon juice. They’re also excellent in vegetarian dishes, as their umami-rich flavor can mimic meat. Store fresh oysters in a paper bag in the refrigerator for up to a week, or dry them for longer preservation.

In Wisconsin, oyster mushrooms are not just a culinary treasure but a gateway to the broader world of foraging. Their accessibility and distinct features make them an ideal starting point for anyone interested in wild edibles. By learning to identify and sustainably harvest these mushrooms, you’ll deepen your connection to the natural world while enjoying a delicious, locally sourced ingredient.

Can You Eat Crimini Mushrooms Raw? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Lion’s Mane: shaggy, white, seafood-like texture, found on dead trees

In the heart of Wisconsin's forests, a peculiar mushroom stands out—the Lion's Mane, scientifically known as *Hericium erinaceus*. Its shaggy, white appearance resembles a cascading waterfall of icicles, making it a striking find on dead or decaying hardwood trees. Unlike the typical cap-and-stem mushrooms, Lion's Mane forms large, globular clusters of spines that can grow up to 20 inches wide, though most foragers find them in the 4- to 12-inch range. Its texture, often compared to crab or lobster meat, has earned it a place in both culinary and medicinal circles. Foraging for Lion's Mane in Wisconsin is best done in late summer to early fall, when the cool, moist conditions favor its growth.

From a culinary perspective, Lion's Mane is a forager's treasure. Its seafood-like texture makes it an excellent meat substitute, particularly when breaded and fried or sautéed in butter. To prepare, gently clean the spines with a brush or damp cloth to remove debris, then tear them into smaller pieces. A simple recipe involves tossing the mushroom in a mixture of flour, garlic powder, and paprika before frying until golden. For a more delicate approach, simmer it in a seafood broth to enhance its natural umami flavor. When cooking, note that Lion's Mane releases moisture quickly, so high heat and short cooking times are ideal. Its versatility extends to soups, stir-fries, and even as a topping for pizzas, making it a must-try for adventurous home cooks.

Beyond its culinary appeal, Lion's Mane is celebrated for its potential health benefits. Studies suggest it contains compounds like erinacines and hericenones, which may stimulate nerve growth factor (NGF) production, supporting brain health and potentially aiding in conditions like Alzheimer's and anxiety. While research is ongoing, many incorporate Lion's Mane into their diets as a tea, tincture, or supplement. A typical dosage for supplements ranges from 500 to 3,000 mg daily, though consulting a healthcare provider is advised. Foraging enthusiasts should also be aware that while Lion's Mane is generally safe, proper identification is crucial, as it can be mistaken for toxic look-alikes like the bearded tooth fungus (*Hericium coralloides*), which is also edible but less desirable.

Foraging for Lion's Mane in Wisconsin requires patience and keen observation. Look for it on oak, maple, and beech trees, often at eye level or higher. Its preference for dead or dying wood means it’s rarely found on healthy trees. When harvesting, use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at its base, leaving enough behind to allow regrowth. Avoid pulling or twisting, as this can damage the mycelium. Foraging ethically also means taking only what you need and leaving some behind to spore and propagate. Pairing this hunt with a field guide or experienced forager can enhance both safety and success, ensuring you bring home the right mushroom for your next culinary or medicinal experiment.

Can You Eat Royksopp Mushrooms? A Guide to Their Edibility

You may want to see also

Chicken of the Woods: bright orange, shelf-like, grows on oak trees

In the heart of Wisconsin's forests, a vibrant spectacle awaits foragers and food enthusiasts alike: Chicken of the Woods, a mushroom that defies the typical earthy tones of its kin. Its bright orange hue and distinctive shelf-like structure make it a standout, often found clinging to the sides of oak trees. This mushroom is not just a visual marvel but also a culinary treasure, offering a texture and flavor that remarkably mimic its namesake, chicken. For those venturing into the woods, identifying this fungus correctly is crucial, as its appearance can vary from fan-shaped clusters to overlapping brackets, each a testament to nature’s artistry.

Foraging for Chicken of the Woods requires both patience and precision. The best time to search is late summer to early fall, when the mushroom thrives in Wisconsin’s temperate climate. Look for mature oak trees, as the fungus forms a symbiotic relationship with these hosts, often returning year after year to the same spot. When harvesting, use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at its base, leaving enough behind to ensure future growth. Avoid specimens that are too close to the ground or show signs of decay, as these may harbor contaminants or parasites. Always cook Chicken of the Woods thoroughly, as consuming it raw can lead to digestive discomfort.

From a culinary perspective, Chicken of the Woods is a versatile ingredient that shines in a variety of dishes. Its meaty texture makes it an excellent candidate for grilling, frying, or sautéing, while its mild flavor pairs well with garlic, thyme, and lemon. For a simple yet satisfying meal, marinate chunks of the mushroom in olive oil, herbs, and spices, then grill until tender and slightly charred. Alternatively, slice it thinly and use it as a plant-based substitute in tacos, stir-fries, or even as a topping for pizza. For the adventurous cook, experimenting with pickling or dehydrating can extend its shelf life and open up new flavor possibilities.

While Chicken of the Woods is a prized find, caution is paramount. Proper identification is critical, as it can be confused with toxic look-alikes such as the Sulphur Shelf or false species that grow on conifers. Always consult a reliable field guide or forage with an experienced guide to avoid mistakes. Additionally, individuals with mushroom allergies or sensitivities should approach with care, starting with small portions to gauge tolerance. Foraging responsibly also means respecting the ecosystem—never overharvest from a single tree, and leave some mushrooms to release spores and perpetuate their lifecycle.

In Wisconsin, Chicken of the Woods is more than just an edible mushroom; it’s a symbol of the state’s rich mycological heritage. Its striking appearance and culinary potential make it a favorite among foragers, while its relationship with oak trees underscores the intricate connections within forest ecosystems. Whether you’re a seasoned forager or a curious cook, this mushroom offers a unique opportunity to engage with nature and elevate your meals. With careful identification, sustainable harvesting, and creative cooking, Chicken of the Woods can transform from a woodland find into a centerpiece of your table.

Are Elm Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging and Consumption

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wisconsin is home to several edible mushroom species, including morels (Morchella spp.), chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius), lion's mane (Hericium erinaceus), oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), and chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus). Always ensure proper identification before consuming.

Yes, some poisonous mushrooms in Wisconsin resemble edible species. For example, false morels (Gyromitra spp.) can be mistaken for true morels, and jack-o’-lantern mushrooms (Omphalotus olearius) look similar to chanterelles. Always consult a field guide or expert if unsure.

The best time to forage for edible mushrooms in Wisconsin varies by species. Morels typically appear in spring (April to June), chanterelles in summer to fall (July to October), and oyster mushrooms in fall (September to November). Always check local conditions and regulations.