When exploring the world of mushrooms, it’s crucial to distinguish between edible and non-edible varieties, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks. While many mushrooms are prized for their culinary uses, others are toxic or even deadly. For instance, the Amanita genus includes some of the most poisonous species, such as the Death Cap, which closely resembles edible mushrooms like the Paddy Straw. Similarly, the False Morel, despite its morel-like appearance, contains toxins that can cause severe illness if not properly prepared. Understanding these distinctions is essential for foragers and enthusiasts to safely enjoy the bounty of edible mushrooms while avoiding dangerous look-alikes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Common Toxic Look-alikes: Identify mushrooms resembling edible ones but are poisonous, like the Amanita genus

- False Morel Dangers: Learn why false morels are toxic despite resembling edible true morels

- Jack-O-Lantern Risks: Understand why the bright orange Jack-O-Lantern mushroom is not safe to eat

- Conocybe Confusion: Distinguish Conocybe filaris, a toxic species, from edible mushrooms in its family

- Deadly Galerina: Recognize Galerina marginata, a deadly mushroom often mistaken for edible species

Common Toxic Look-alikes: Identify mushrooms resembling edible ones but are poisonous, like the Amanita genus

The forest floor is a minefield of deception, where toxic mushrooms masquerade as their edible cousins. Among the most notorious imposters are species from the Amanita genus, whose elegant appearance often lures foragers into a dangerous mistake. Take the Amanita bisporigera, for instance—its pristine white cap and slender stem resemble the edible Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) at a glance. Yet, a single cap of the former contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney damage, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion. Misidentification here isn’t just a mistake; it’s a potential fatality.

To avoid falling victim to these toxic look-alikes, focus on key distinguishing features. Edible mushrooms like the Meadow Mushroom (Agaricus campestris) typically have pink or brown gills, while Amanita species often display white gills and a volva—a cup-like structure at the base of the stem. Another red flag is the presence of a ring on the Amanita stem, absent in most edible varieties. Foraging without a reliable guide or expert companion is akin to navigating a labyrinth blindfolded. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources, and when in doubt, discard the specimen entirely.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to accidental poisoning, as they’re drawn to the Amanita’s striking appearance. Teach kids to avoid touching or tasting wild mushrooms, and keep pets on a leash during woodland walks. If ingestion is suspected, immediate medical attention is critical. Amatoxins can be neutralized if treated within 6–12 hours, but delays often lead to irreversible organ damage. Hospitals may administer activated charcoal or perform gastric lavage to reduce toxin absorption, followed by supportive care to stabilize vital functions.

The allure of wild mushroom foraging lies in its rewards, but the risks demand respect and vigilance. Equip yourself with a magnifying glass, a knife for spore prints, and a field guide tailored to your region. Note habitat details—Amanitas often grow near birch or oak trees, while edible species like Chanterelles prefer mossy environments. Remember, no meal is worth risking your health. The forest’s beauty is in its complexity, but its dangers are equally intricate. Foraging is an art honed through patience, practice, and an unwavering commitment to safety.

Are All White Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

False Morel Dangers: Learn why false morels are toxic despite resembling edible true morels

False morels, with their brain-like appearance and springtime emergence, often lure foragers into a dangerous misconception: they look like their edible counterparts, true morels, so they must be safe to eat. This assumption is a grave mistake. While true morels are a culinary delight, false morels contain a toxic compound called gyromitrin, which breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a potent toxin affecting the nervous system and liver. Even small amounts can cause severe symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, and in extreme cases, seizures or coma.

The toxicity of false morels is insidious. Unlike some poisonous mushrooms that cause immediate reactions, symptoms from false morels can take hours or even days to appear. This delayed onset often leads people to believe the mushrooms are safe, only to be blindsided by illness later. Compounding the danger is the fact that false morels are not uniformly toxic; some individuals may consume them without issue, while others suffer severely. This variability makes it impossible to gauge safety based on anecdotal evidence.

Distinguishing false morels from true morels requires careful observation. True morels have a hollow stem and a honeycomb-like cap with distinct pits and ridges. False morels, on the other hand, often have a wrinkled, brain-like cap and a cottony or chambered interior. Their stems may also be thicker and more substantial. However, these differences can be subtle, especially to inexperienced foragers. If in doubt, err on the side of caution and avoid consumption entirely.

For those determined to forage, thorough cooking can reduce, but not eliminate, the toxicity of false morels. Boiling them in water for at least 15 minutes and discarding the liquid can help break down gyromitrin, but this method is not foolproof. Even cooked false morels pose a risk, particularly for children, the elderly, or individuals with compromised immune systems. The safest approach is to avoid false morels altogether and focus on confidently identifying true morels or purchasing mushrooms from reputable sources.

In the world of mushroom foraging, the allure of a bountiful harvest must always be tempered by caution. False morels serve as a stark reminder that appearances can be deceiving. By understanding their toxicity, learning to identify them accurately, and prioritizing safety over curiosity, foragers can enjoy the rewards of the forest without risking their health. The true morel’s delicate flavor and texture are worth the effort to find—just make sure you’re not mistaken for its toxic doppelgänger.

Are Amanita Mushrooms Edible? Exploring Safety and Risks

You may want to see also

Jack-O-Lantern Risks: Understand why the bright orange Jack-O-Lantern mushroom is not safe to eat

The Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, with its vibrant orange glow, might tempt foragers with its striking appearance, but it’s a prime example of nature’s deception. Unlike its edible look-alikes, such as the chanterelle, this fungus contains illudin M and illudin S, toxins that cause severe gastrointestinal distress. Ingesting even a small amount can lead to symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration within hours. Foraging without expertise can turn a woodland adventure into a hospital visit, making identification accuracy critical.

Analyzing the risks, the Jack-O-Lantern’s toxicity isn’t just about discomfort—it’s about misidentification. Its bright color and bioluminescent properties often attract attention, but these features are red flags, not endorsements. Unlike edible mushrooms that thrive in specific habitats, Jack-O-Lanterns grow on wood, particularly deciduous trees, and their clustered appearance can mimic benign species. Foragers should note that while cooking destroys some toxins in certain mushrooms, the Jack-O-Lantern’s toxins remain active, rendering preparation methods ineffective.

Persuasively, avoiding the Jack-O-Lantern isn’t just a suggestion—it’s a necessity. Its toxins can cause prolonged illness, especially in children or those with compromised immune systems. A single misidentified mushroom can ruin a meal or worse. Practical tips include carrying a reliable field guide, using a spore print test (Jack-O-Lanterns produce green spores), and consulting experienced foragers. If in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

Comparatively, while some toxic mushrooms, like the Death Cap, are deadly, the Jack-O-Lantern’s effects are more immediate and predictable. Its symptoms, though severe, rarely lead to fatalities if treated promptly. However, its widespread presence in North America and Europe increases the likelihood of accidental ingestion. Unlike other toxic species that blend into their surroundings, the Jack-O-Lantern’s bold appearance makes it a frequent culprit in foraging mishaps, underscoring the need for vigilance.

Descriptively, the Jack-O-Lantern’s allure lies in its eerie beauty—its lantern-like glow in the dark and vivid orange gills. Yet, this beauty masks its danger. Its texture, firm yet slippery, and its woody base are telltale signs of its toxicity. Foragers should focus on these details rather than its captivating color. By understanding its unique characteristics and risks, enthusiasts can appreciate its role in the ecosystem without endangering themselves, turning knowledge into a shield against its deceptive charm.

Are Ghost Mushrooms Edible? Unveiling the Truth About Omphalotus Olearius

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Conocybe Confusion: Distinguish Conocybe filaris, a toxic species, from edible mushrooms in its family

Conocybe filaris, a toxic mushroom, often lurks in grassy areas alongside its edible relatives, making identification critical for foragers. This species contains the psychoactive compound coniine, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in rare cases, seizures or respiratory failure if ingested in quantities as small as 10-20 grams. Unlike its harmless cousins, *Conocybe filaris* has a distinctively slender, cylindrical stipe and a bell-shaped cap that fades from tan to pale yellow with age. Its gills, initially pale, darken to a rusty brown as the spores mature, a feature that can mislead even experienced collectors.

To distinguish *Conocybe filaris* from edible species like *Conocybe tenera* or *Bolbitius titubans*, focus on three key characteristics. First, examine the spore print: *C. filaris* produces a rusty-brown print, while edible relatives often yield lighter shades. Second, note the habitat: *C. filaris* prefers disturbed soils, such as lawns or gardens, whereas edible species are more commonly found in wooded areas. Third, inspect the cap surface under a magnifying lens—*C. filaris* often exhibits fine, radial fibrils, a trait less pronounced in its edible counterparts.

Foraging safely requires a methodical approach. Always carry a field guide or consult a mycologist when in doubt. Avoid collecting mushrooms in areas treated with pesticides or fertilizers, as these chemicals can accumulate in fungal tissues. If you suspect ingestion of *Conocybe filaris*, seek medical attention immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Symptoms typically appear within 30 minutes to 2 hours and may include nausea, vomiting, and dizziness.

The allure of wild mushrooms lies in their diversity, but this very trait demands caution. *Conocybe filaris* serves as a cautionary example of how closely toxic species can resemble edible ones. By mastering specific identification techniques and respecting the risks, foragers can enjoy the bounty of the forest without endangering their health. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

Are Shield Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Identification and Consumption

You may want to see also

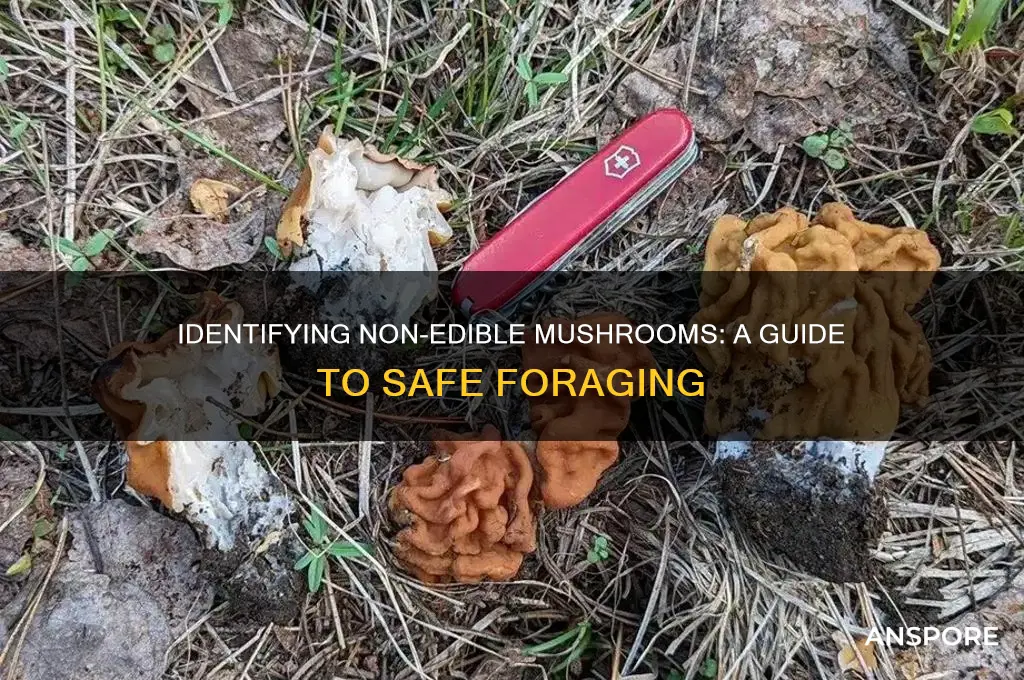

Deadly Galerina: Recognize Galerina marginata, a deadly mushroom often mistaken for edible species

Galerina marginata, commonly known as the Deadly Galerina, is a mushroom that demands your attention. Often lurking in woodchip mulch and decaying wood, this small, nondescript fungus is responsible for numerous cases of accidental poisoning worldwide. Its unassuming appearance belies its deadly nature, as it contains amatoxins, the same toxins found in the infamous Death Cap mushroom. Ingesting just one Deadly Galerina can lead to severe liver and kidney damage, and without prompt medical intervention, the outcome is often fatal. Recognizing this mushroom is crucial, especially for foragers who might mistake it for edible lookalikes.

To identify Galerina marginata, focus on its key features. It typically grows in clusters on wood, with a small, brown cap that ranges from 1 to 4 centimeters in diameter. The cap often has a distinctive sticky or slimy texture when moist, and the edges may be slightly curved inward. The gills are brown and closely spaced, and the stem is slender, often with a faint ring zone—a remnant of a partial veil. One of its most deceptive traits is its resemblance to edible mushrooms like the Honey Mushroom (Armillaria spp.) or the Paddy Straw Mushroom (Volvariella volvacea). However, unlike these species, the Deadly Galerina has rusty-brown spores, which can be verified with a spore print.

Mistaking Galerina marginata for an edible species is a grave error, but it’s one that can be avoided with careful observation. Always examine the habitat—this mushroom’s preference for wood is a red flag. Additionally, note the absence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and the presence of the faint ring zone on the stem. Foraging without a reliable field guide or expert guidance is risky, especially in regions where Deadly Galerina thrives, such as North America, Europe, and Asia. If in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth the risk of amatoxin poisoning.

The consequences of ingesting Galerina marginata are severe and swift. Symptoms typically appear 6 to 24 hours after consumption, starting with gastrointestinal distress—vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These initial signs may subside, giving a false sense of recovery, but within 2 to 4 days, liver and kidney failure set in, often leading to coma or death. Treatment involves hospitalization, where supportive care and, in some cases, liver transplantation may be necessary. Survival rates are low, emphasizing the critical importance of accurate identification and avoidance.

In the world of mushroom foraging, knowledge is your best defense. Galerina marginata’s deadly nature and deceptive appearance make it a prime example of why caution is paramount. By familiarizing yourself with its characteristics and understanding its dangers, you can enjoy the hobby of foraging without falling victim to this silent killer. Remember, when it comes to mushrooms, certainty is non-negotiable—if you’re not 100% sure, it’s not worth the risk.

Are Brown Cup Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Identification and Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the Amanita ocreata, also known as the death angel, is highly toxic and not edible.

No, the Conocybe filaris is a poisonous mushroom and should not be eaten.

No, the Galerina marginata is toxic and not safe for consumption.

No, the Lepiota brunneoincarnata is poisonous and not an edible mushroom.

No, the Clitocybe dealbata, also known as the ivory funnel, is toxic and not edible.