Mushrooms that grow on poplar trees, often referred to as poplar mushrooms, are a fascinating subset of fungi that thrive in symbiotic or saprophytic relationships with these deciduous trees. Poplars, known for their rapid growth and widespread presence in temperate forests, provide an ideal substrate for various mushroom species. Among the most notable are the oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which frequently colonize decaying poplar wood, and the artist's conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), a bracket fungus that grows on both living and dead poplar trees. Additionally, species like the velvet shank (*Flammulina velutipes*) and certain types of *Tricholoma* mushrooms are often found near or on poplar roots. Understanding which mushrooms grow on poplar not only sheds light on forest ecology but also highlights potential culinary, medicinal, or ecological uses of these fungi.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Oyster Mushrooms: Poplar trees often host oyster mushrooms, which thrive on decaying wood

- Turkey Tail: This bracket fungus commonly grows on poplar, aiding in wood decomposition

- Chaga: A parasitic fungus found on poplar, known for its medicinal properties

- Birch Polypore: Occasionally grows on poplar, resembling birch trees' preferred host

- Artist's Conk: Large bracket fungus that colonizes poplar, causing wood decay over time

Oyster Mushrooms: Poplar trees often host oyster mushrooms, which thrive on decaying wood

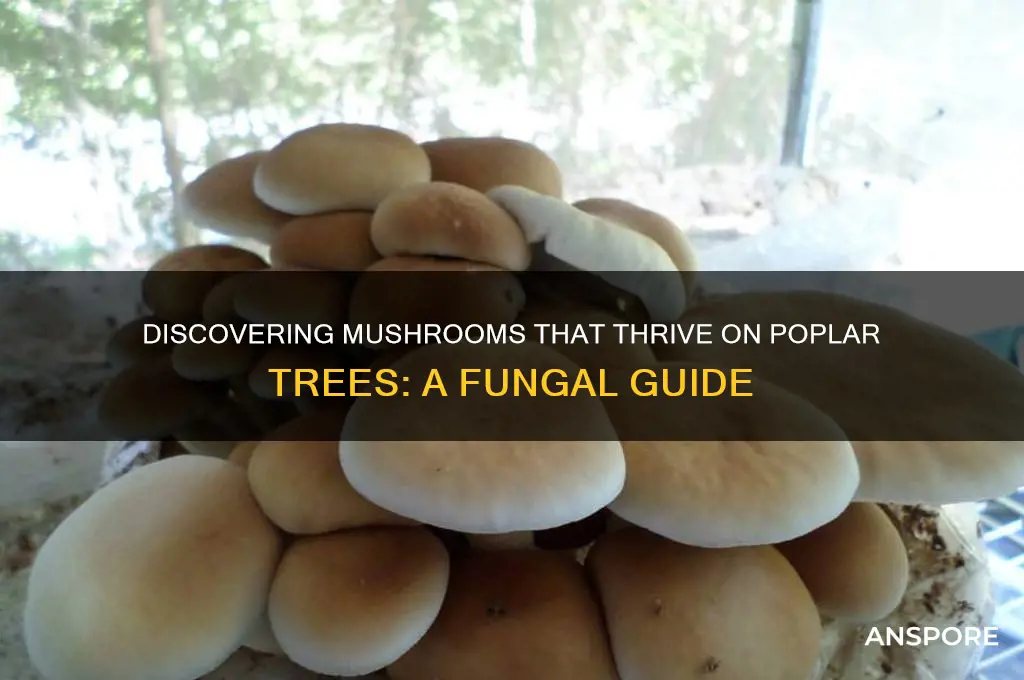

Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are a common and highly valued fungus that frequently colonizes poplar trees, particularly those with decaying wood. Poplar trees, known for their fast growth and soft wood, provide an ideal substrate for oyster mushrooms as their wood begins to break down. These mushrooms are saprotrophic, meaning they play a crucial role in decomposing dead or dying wood, returning nutrients to the ecosystem. When poplar trees age or suffer damage, their wood becomes susceptible to fungal colonization, and oyster mushrooms are often among the first to take advantage of this resource.

The relationship between oyster mushrooms and poplar trees is symbiotic in the context of forest health. While the mushrooms benefit from the nutrients in the decaying wood, they also aid in the natural recycling process, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler forms. This makes oyster mushrooms not only a fascinating species but also an ecologically important one. Foragers and cultivators often seek out poplar stands when hunting for oyster mushrooms, as these trees are reliable hosts. The mushrooms typically grow in clusters, forming fan-like caps that range in color from grayish-brown to pale white, depending on their maturity.

Cultivating oyster mushrooms on poplar wood is a practice embraced by many mushroom farmers. Poplar logs or chips are inoculated with oyster mushroom spawn, and over several months, the mycelium colonizes the wood before fruiting bodies emerge. This method mimics the natural process of colonization in the wild, making it sustainable and efficient. Poplar’s low resin content and high lignin-cellulose ratio make it particularly suitable for oyster mushroom cultivation, as these characteristics allow the fungus to easily break down the wood fibers.

For those interested in foraging, identifying oyster mushrooms on poplar trees requires careful observation. Look for clusters of shelf-like mushrooms growing directly on the bark or exposed wood of the tree. The gills on the underside of the cap and the absence of a distinct stem are key features for identification. However, foragers should always exercise caution and ensure proper identification, as some toxic mushrooms can resemble oyster mushrooms. Additionally, it’s important to forage responsibly, avoiding over-harvesting to preserve the natural balance of the ecosystem.

In conclusion, oyster mushrooms and poplar trees share a significant ecological and practical relationship. Poplar’s decaying wood provides an optimal environment for oyster mushrooms to thrive, both in the wild and in cultivation. Understanding this relationship not only enhances our appreciation of forest ecosystems but also offers valuable insights for sustainable mushroom farming. Whether you’re a forager, farmer, or nature enthusiast, the connection between oyster mushrooms and poplar trees is a fascinating example of nature’s interdependence.

Aquarium Cultivation: Growing Psilocybin Mushrooms in a Controlled Environment

You may want to see also

Turkey Tail: This bracket fungus commonly grows on poplar, aiding in wood decomposition

Turkey Tail, scientifically known as *Trametes versicolor*, is a bracket fungus that frequently colonizes poplar trees, among other hardwoods. This fungus is easily recognizable by its fan-shaped, multicolored caps that resemble the tail feathers of a turkey, hence its common name. It thrives in temperate forests where poplar trees are abundant, forming clusters or tiered shelves on both living and dead wood. Turkey Tail is not only a striking presence in the forest but also plays a crucial role in the ecosystem by aiding in the decomposition of wood, breaking down complex lignin and cellulose into simpler compounds.

The relationship between Turkey Tail and poplar trees is symbiotic in the context of forest ecology. While the fungus benefits by obtaining nutrients from the wood, it accelerates the natural process of decay, returning essential elements to the soil. This decomposition process is vital for nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems, ensuring that minerals and organic matter are recycled and made available to other organisms. Poplar trees, being fast-growing and widespread, provide an ideal substrate for Turkey Tail, as their wood is rich in the nutrients the fungus requires to thrive.

Identifying Turkey Tail on poplar is relatively straightforward due to its distinctive appearance. The upper surface of the fungus displays concentric zones of color, ranging from browns and tans to blues and greens, while the underside features a creamy white pore surface. It typically grows in overlapping clusters, often covering large areas of the tree's bark or exposed wood. Foragers and nature enthusiasts should note that while Turkey Tail is non-toxic, it is tough and inedible, making it more valuable for its ecological role than culinary use.

Cultivating an environment conducive to Turkey Tail growth on poplar involves maintaining healthy forest conditions. Fallen or decaying poplar logs provide the perfect habitat for this fungus, as it prefers moist, shaded areas. Landowners and forest managers can encourage Turkey Tail by leaving deadwood in place rather than removing it, thereby supporting biodiversity and natural decomposition processes. Additionally, reducing pollution and chemical use in forested areas can help ensure the fungus thrives, as it is sensitive to environmental contaminants.

Beyond its ecological significance, Turkey Tail has gained attention for its potential medicinal properties. Research has shown that it contains compounds like polysaccharide-K (PSK), which have been studied for their immune-boosting and anti-cancer effects. While this aspect is not directly related to its growth on poplar, it highlights the broader importance of preserving fungi like Turkey Tail in their natural habitats. By understanding and appreciating the role of Turkey Tail in wood decomposition on poplar trees, we can better protect and manage forest ecosystems for future generations.

Mastering Monotub Cultivation: Growing Lion's Mane Mushrooms at Home

You may want to see also

Chaga: A parasitic fungus found on poplar, known for its medicinal properties

Chaga, scientifically known as *Inonotus obliquus*, is a unique parasitic fungus that primarily grows on birch trees but can also be found on poplar trees in certain regions. Unlike typical mushrooms, Chaga forms a hard, woody conk that resembles burnt charcoal, making it easily identifiable on the bark of its host tree. This fungus is not a mushroom in the conventional sense, as it lacks the fruiting body structure commonly associated with mushrooms. Instead, its value lies in its sclerotium, a dense mass of mycelium that develops over years, drawing nutrients from the tree. Poplar trees, particularly in colder climates, provide a suitable environment for Chaga’s growth, though it is less commonly found on these trees compared to birch.

Chaga is renowned for its potent medicinal properties, which have been recognized in traditional medicine systems, particularly in Eastern Europe, Russia, and Northern Asia, for centuries. Its sclerotium is rich in bioactive compounds, including beta-glucans, polyphenols, and melanin, which contribute to its therapeutic effects. These compounds are believed to boost the immune system, reduce inflammation, and exhibit antioxidant properties. Modern research supports many of these claims, with studies highlighting Chaga’s potential to combat oxidative stress, support immune function, and even inhibit the growth of certain cancer cells. Its high antioxidant content, particularly superoxide dismutase (SOD), makes it a popular ingredient in health supplements and teas.

Harvesting Chaga from poplar or birch trees requires careful consideration to ensure sustainability. The fungus grows slowly, taking 10 to 20 years to reach maturity, and overharvesting can harm both the fungus and its host tree. Ethical harvesters leave a portion of the conk on the tree to allow regrowth and minimize damage. Additionally, Chaga should only be collected from trees in pristine environments to avoid contamination from pollutants, which can compromise its medicinal qualities. When sourcing Chaga, it is essential to verify its origin and ensure it has been sustainably and responsibly harvested.

Preparing Chaga for consumption involves extracting its beneficial compounds, typically through a long decoction process. The hard sclerotium is chopped into small pieces and simmered in water for several hours to create a potent tea. This method ensures the release of its bioactive components, resulting in a dark, earthy beverage. Chaga tea is often consumed for its health benefits, but it can also be found in powdered, capsule, or tincture forms for convenience. Its bitter taste is often balanced with honey or other natural sweeteners to make it more palatable.

While Chaga’s medicinal properties are well-documented, it is important to approach its use with caution. Individuals with certain medical conditions, such as autoimmune disorders or those on blood-thinning medications, should consult a healthcare professional before incorporating Chaga into their regimen. Additionally, the quality and source of Chaga products can vary widely, so purchasing from reputable suppliers is crucial. Despite these considerations, Chaga remains a fascinating example of the symbiotic relationship between fungi and trees, offering a natural remedy with a rich history and promising health benefits. Its presence on poplar trees, though less common, underscores the adaptability of this remarkable fungus and its potential to thrive in diverse environments.

Reviving Spores: Growing Mushrooms from Dried Samples at Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Birch Polypore: Occasionally grows on poplar, resembling birch trees' preferred host

The Birch Polypore (*Piptoporus betulinus*), as its name suggests, is most commonly associated with birch trees, where it thrives as a saprotrophic fungus, breaking down dead or decaying wood. However, it is not exclusive to birch and can occasionally be found growing on poplar trees, particularly in environments where both tree species are present. This adaptability highlights the Birch Polypore’s ability to colonize a variety of deciduous trees, though its preference for birch remains dominant. When it does appear on poplar, it often resembles its typical growth on birch, making it a fascinating example of fungal versatility.

Identifying Birch Polypore on poplar requires careful observation, as its appearance remains consistent across host trees. The fruiting body is bracket-like, with a creamy white to silvery-gray upper surface that may darken with age. The pores on the underside are initially white but turn yellowish-brown as the mushroom matures. Its tough, leathery texture is a defining characteristic, making it durable enough to persist through multiple seasons. When found on poplar, it typically grows on wounded or dead sections of the tree, mirroring its role as a decomposer on birch.

The presence of Birch Polypore on poplar is relatively rare compared to its prevalence on birch, but it underscores the fungus’s ability to adapt to similar wood compositions. Poplar, like birch, has a relatively soft wood that is conducive to fungal colonization. However, the Birch Polypore’s occasional appearance on poplar may also depend on environmental factors, such as humidity, temperature, and the availability of suitable substrates. Foragers and mycologists should note that while it is non-toxic, the Birch Polypore is not typically consumed due to its tough texture, though it has historical uses in tinder production and traditional medicine.

For those interested in finding Birch Polypore on poplar, it is instructive to focus on older or injured trees, as these provide the ideal conditions for fungal growth. The mushroom often appears singly or in small clusters, attached directly to the bark or exposed wood. Its resemblance to its birch-grown counterparts makes it a valuable subject for studying fungal host preferences and ecological adaptability. Observing Birch Polypore on poplar also offers insights into how fungi exploit available resources in diverse forest ecosystems.

In conclusion, while the Birch Polypore is primarily a fungus of birch trees, its occasional growth on poplar demonstrates its ability to thrive on alternative hosts with similar wood characteristics. This adaptability makes it a noteworthy species for both mycological study and ecological observation. Foraging for Birch Polypore on poplar requires attention to detail, as its appearance and habitat preferences remain consistent across tree species. Understanding its behavior on poplar enriches our knowledge of fungal ecology and highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems.

Exploring Rainforest Fungi: Do Mushrooms Thrive in Tropical Ecosystems?

You may want to see also

Artist's Conk: Large bracket fungus that colonizes poplar, causing wood decay over time

The Artist's Conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*), a striking and ecologically significant bracket fungus, is a common sight on poplar trees, where it plays a dual role as both a decomposer and a canvas for human creativity. This large, perennial fungus colonizes poplars by infiltrating the wood through wounds, cracks, or branch stubs, gradually establishing a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. Over time, the mycelium secretes enzymes that break down complex wood components like cellulose and lignin, leading to white rot and structural decay. While this process is detrimental to the tree, it is a natural part of forest ecosystems, recycling nutrients back into the soil.

The fruiting bodies of the Artist's Conk are its most recognizable feature, appearing as thick, brown, fan-shaped brackets that often grow in tiered clusters on the trunk or branches of poplars. These brackets can reach impressive sizes, sometimes exceeding 30 centimeters in diameter, and are characterized by a varnished, dark brown upper surface and a white to grayish underside with visible pores. The name "Artist's Conk" derives from the fungus's unique ability to serve as a medium for drawing or etching. When the pore surface is scratched or marked, the exposed tissue darkens over time, creating permanent, natural "artwork."

Identifying Artist's Conk on poplars is relatively straightforward due to its distinctive appearance and growth habit. It typically grows directly on the bark, often low on the trunk or near the base of the tree, where moisture levels are higher. Unlike some other wood-decay fungi, it does not produce gills or a stipe, adhering closely to the substrate. Its presence is a clear indicator of internal wood decay, which can weaken the tree and make it more susceptible to wind damage or other stressors.

For landowners or arborists, the discovery of Artist's Conk on poplars signals the need for assessment and management. While the fungus itself cannot be eradicated once established, measures can be taken to slow its spread and mitigate risks. Pruning dead or infected branches, improving tree health through proper watering and fertilization, and monitoring for structural instability are all recommended practices. In some cases, removal of severely compromised trees may be necessary to prevent hazards.

From an ecological perspective, Artist's Conk plays a vital role in nutrient cycling and habitat creation. As it decays wood, it releases nutrients that support other organisms, from bacteria and insects to plants. Additionally, its brackets provide shelter and food for various invertebrates, contributing to biodiversity. For foragers and enthusiasts, it is important to note that Artist's Conk is not edible and has no known medicinal properties, though it has been studied for its unique chemical compounds. Its true value lies in its ecological function and its ability to inspire human creativity through its natural "canvas."

Do Magic Mushrooms Thrive on Cow Manure? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms that commonly grow on poplar trees include *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom), *Trametes versicolor* (turkey tail), *Ganoderma applanatum* (artist's conk), and *Fomes fomentarius* (tinder fungus).

Not all mushrooms growing on poplar trees are safe to eat. While some, like oyster mushrooms, are edible, others, such as certain bracket fungi, are inedible or toxic. Always consult a mycologist or field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.

Mushrooms grow on poplar trees because these trees often provide a suitable substrate for fungal growth, especially when the wood is decaying. Poplars are also susceptible to certain fungal infections, creating an environment conducive to mushroom development.

Yes, some mushrooms growing on poplar trees, particularly those associated with wood decay (like conks and bracket fungi), can indicate fungal infections that weaken or kill the tree over time. However, saprotrophic fungi help decompose dead wood, playing a natural role in ecosystems.