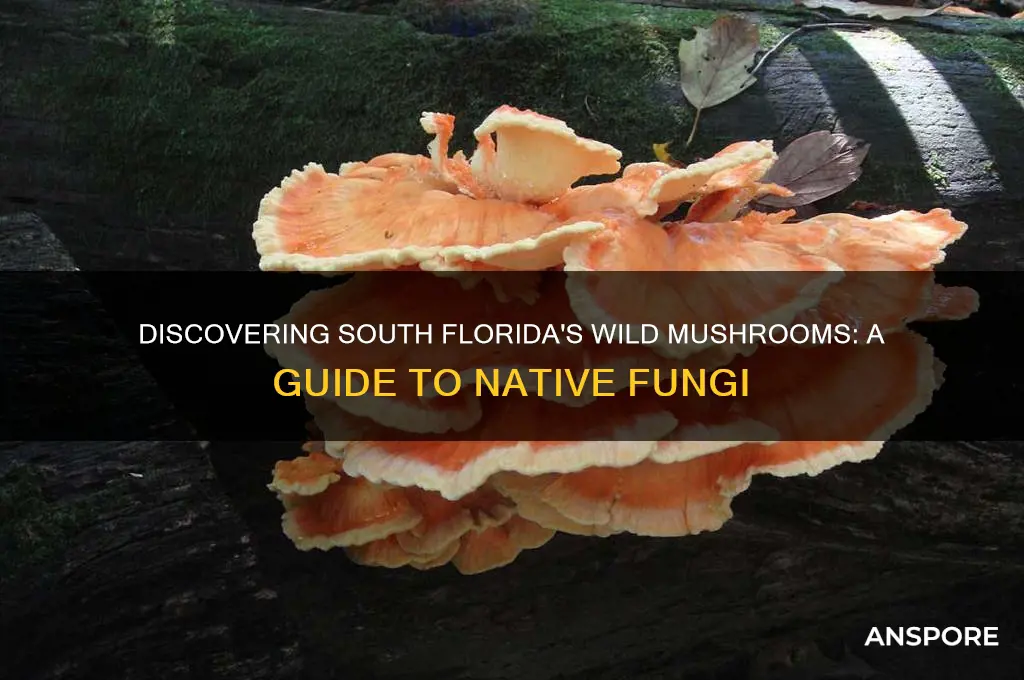

South Florida's unique subtropical climate and diverse ecosystems provide a fertile ground for a variety of wild mushrooms to thrive. From the lush Everglades to the urban green spaces, the region supports an array of fungal species, each adapted to its specific environment. While some mushrooms are easily recognizable, like the vibrant Amanita muscaria or the delicate Mycena species, others remain hidden gems, known only to avid foragers and mycologists. Exploring what mushrooms grow wild in South Florida not only reveals the richness of local biodiversity but also highlights the importance of understanding these organisms in their natural habitats, as many play crucial roles in ecosystem health and can vary significantly in edibility and toxicity.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Mushrooms: Identify safe, edible species like the Field Mushroom and Oyster Mushroom

- Toxic Mushroom Varieties: Learn about poisonous species such as the Deadly Amanita and Conocybe

- Mushroom Foraging Tips: Best practices for safely harvesting wild mushrooms in South Florida

- Seasonal Growth Patterns: Understand when and where mushrooms thrive in local ecosystems

- Ecosystem Roles: Explore how wild mushrooms contribute to South Florida’s biodiversity

Common Edible Mushrooms: Identify safe, edible species like the Field Mushroom and Oyster Mushroom

South Florida's warm, humid climate supports a variety of wild mushrooms, but identifying safe, edible species is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes. Among the common edible mushrooms found in this region, the Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris) stands out as a popular choice. This mushroom is easily recognizable by its white to light brown cap, which can range from 2 to 8 inches in diameter. The gills are initially pink and turn dark brown as the mushroom matures. The Field Mushroom grows in grassy areas, such as lawns and fields, often appearing after rainfall. When foraging, ensure the cap is not slimy, and the base of the stem is bulbous, as these are key identifiers. Always avoid mushrooms with red or yellow coloration on the cap or stem, as these could be poisonous species.

Another safe and delicious option is the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), which thrives in South Florida's wooded areas. This mushroom is named for its oyster shell-like shape and grows in clusters on dead or decaying wood, particularly hardwood trees like oak and beech. The caps are typically grayish-brown or tan, with a smooth, velvety texture. Oyster Mushrooms have a mild, savory flavor and are a favorite among foragers. To identify them correctly, look for their decurrent gills (gills that run down the stem) and lack of a distinct ring on the stem. Be cautious of mushrooms growing on coniferous trees, as some toxic species resemble Oyster Mushrooms but are unsafe to consume.

The Lion's Mane Mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) is another edible species found in South Florida, often growing on hardwood trees. This unique mushroom resembles a cascading clump of white spines, giving it a distinctive appearance. Lion's Mane is prized for its seafood-like texture and cognitive health benefits. When identifying, ensure the spines are long and dangling, and the mushroom is free from discoloration or decay. It typically grows in the late summer and fall, making it a seasonal find.

Foragers in South Florida may also encounter the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), a golden-yellow mushroom with a fruity aroma. Chanterelles have forked gills and a wavy cap, often growing in clusters under oak and pine trees. Their vibrant color and peppery taste make them a sought-after edible species. To avoid confusion, note that Chanterelles do not have true gills but rather ridges and forks under the cap. Always inspect the mushroom’s underside to confirm its identity.

Lastly, the Wood Ear (Auricularia polytricha) is a common edible mushroom in South Florida, often found on dead branches or logs. This jelly-like fungus has a dark brown, ear-shaped cap and a slightly crunchy texture when fresh. Wood Ear is widely used in Asian cuisine for its ability to absorb flavors. When foraging, look for its rubbery consistency and smooth surface. While it is safe to eat, it’s best used as a culinary additive rather than a standalone dish due to its mild flavor.

When foraging for these edible mushrooms, always follow best practices: carry a reliable field guide, use a knife to cut mushrooms at the base, and avoid over-harvesting to preserve the ecosystem. If in doubt, consult an expert or mycological group to confirm your findings. Safe and informed foraging ensures a rewarding experience while enjoying South Florida’s wild mushroom bounty.

Ojai's February Fungal Finds: Exploring Winter Mushrooms in the Valley

You may want to see also

Toxic Mushroom Varieties: Learn about poisonous species such as the Deadly Amanita and Conocybe

South Florida's warm, humid climate supports a diverse array of wild mushrooms, but among them are several toxic species that pose serious risks to foragers and curious individuals. Two of the most dangerous varieties found in this region are the Deadly Amanita and Conocybe species. These mushrooms are not only poisonous but can be lethal if ingested, making it crucial to learn their identifying features and habitats.

The Deadly Amanita (Amanita species) is perhaps the most notorious toxic mushroom worldwide, and several varieties can be found in South Florida. These mushrooms often have a distinctive appearance, featuring a cap with white or colored patches (known as warts), a ring on the stem (partial veil remnants), and a bulbous base. The Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) and Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) are particularly dangerous species within this genus. They contain potent toxins called amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to organ failure and death if left untreated. Foragers must avoid any Amanita species, as their resemblance to edible mushrooms like the Paddy Straw mushroom can be deceiving.

Another toxic genus to be aware of is Conocybe, which includes species like Conocybe filaris, commonly known as the "Filamentous Conocybe." These small, unassuming mushrooms often grow in lawns, gardens, and disturbed soils across South Florida. Conocybe species contain the same amatoxins found in Deadly Amanitas, making them equally dangerous. Their slender stems, conical to bell-shaped caps, and rusty brown spores are key identifiers. Despite their less striking appearance compared to Amanitas, their toxicity is just as lethal, and they are often overlooked due to their size and common habitats.

Identifying toxic mushrooms requires careful observation of characteristics such as cap color, gill arrangement, spore color, and habitat. However, even experienced foragers can mistake poisonous species for edible ones, especially in the diverse ecosystems of South Florida. It is essential to follow the rule: never consume a wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If ingestion of a toxic mushroom is suspected, immediate medical attention is critical, as symptoms may not appear for several hours but can rapidly worsen.

In South Florida, where mushroom foraging is gaining popularity, education about toxic species like the Deadly Amanita and Conocybe is paramount. Local mycological societies and field guides can provide valuable resources for learning about these dangerous fungi. By understanding their characteristics and habitats, individuals can safely enjoy the beauty of wild mushrooms without risking their health. Always remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

Cultivating Lobster Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Garden Growing Guide

You may want to see also

Mushroom Foraging Tips: Best practices for safely harvesting wild mushrooms in South Florida

South Florida’s unique subtropical climate supports a variety of wild mushrooms, including species like the Indigo Milk Cap (*Lactarius indigo*), the Florida Bolete (*Butyriboletus floridanus*), and the Common Puffball (*Lycoperdon perlatum*). Before venturing out, educate yourself on these local species through field guides or apps like iNaturalist. Familiarize yourself with their distinctive features, such as cap shape, gill structure, and spore color. Equally important is learning about toxic look-alikes, such as the poisonous Amanita species, which can be deadly if misidentified. Always carry a reliable guidebook or consult with a local mycological society to ensure accuracy.

When foraging, prioritize safety by adhering to ethical and sustainable practices. Only harvest mushrooms you can confidently identify, and never consume anything unless you are 100% sure of its edibility. Use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at the base of the stem, leaving the mycelium undisturbed to allow future growth. Avoid over-harvesting by taking only a few specimens from each patch, ensuring the ecosystem remains balanced. Wear appropriate gear, such as gloves and long sleeves, to protect against insects, thorns, and potential irritants found in South Florida’s dense vegetation.

Timing and location are critical for successful foraging. South Florida’s rainy season, typically from June to October, is the best time to find mushrooms, as they thrive in moist, humid conditions. Look for them in wooded areas, such as Everglades National Park or local nature preserves, where organic matter is abundant. Avoid areas near roadsides or agricultural fields, as mushrooms in these locations may be contaminated by pollutants or pesticides. Always obtain permission when foraging on private land and respect park regulations to avoid legal issues.

Proper handling and storage are essential to preserve the quality and safety of your harvest. Use a mesh bag or basket to carry mushrooms, allowing spores to disperse and promote future growth. Avoid plastic bags, as they can cause condensation and spoilage. Once home, clean the mushrooms gently with a brush or damp cloth to remove dirt and debris. If you plan to consume them, cook thoroughly, as some wild mushrooms contain toxins that are neutralized by heat. Label and store any leftover mushrooms properly, and consider documenting your finds with photos and notes to improve your identification skills over time.

Finally, approach mushroom foraging with humility and a willingness to learn. South Florida’s fungal diversity is vast, and even experienced foragers can encounter unfamiliar species. Joining local foraging groups or workshops can provide valuable hands-on experience and mentorship. Remember, the goal is not just to harvest mushrooms but to deepen your connection with nature while minimizing your impact on the environment. By following these best practices, you can safely enjoy the rewarding hobby of mushroom foraging in South Florida.

Enhance Your Mushroom Harvest: Secrets to Growing Flavorful Fungi

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Growth Patterns: Understand when and where mushrooms thrive in local ecosystems

South Florida's subtropical climate creates unique conditions for wild mushroom growth, with seasonal patterns heavily influenced by rainfall, temperature, and humidity. Unlike temperate regions, where mushrooms often thrive in fall, South Florida's fungal activity peaks during the wet season, typically from June to October. This period coincides with the region's rainy season, providing the moisture necessary for mycelium to fruit. Mushrooms like the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) and Field Mushroom (Agaricus campestris) are commonly spotted during these months, often appearing in clusters on decaying wood or grassy areas. Understanding this seasonal rhythm is crucial for foragers, as it maximizes the chances of finding these species in their prime.

During the dry season, from November to May, mushroom activity in South Florida significantly decreases due to reduced rainfall and lower humidity. However, certain species adapted to drier conditions may still appear, particularly after sporadic rainfall or in microclimates with retained moisture. The Florida Waxycap (Hygrocybe floridanica), a native species, is one such example, occasionally found in shaded, moist areas like hardwood hammocks. Foragers should focus on these specific habitats during the dry season, as they provide the residual moisture needed for fungal growth. This seasonal shift highlights the importance of knowing both the timing and location of mushroom activity in South Florida's ecosystems.

Soil type and habitat play a critical role in determining where mushrooms thrive in South Florida. Species like the Amanita muscaria (Fly Agaric) and Lactarius indigo (Indigo Milk Cap) prefer the acidic soils of pine forests and hardwood hammocks, which are abundant in the region. These habitats retain moisture better than sandy soils, fostering fungal growth even during less rainy periods. Conversely, mushrooms like the Coprinus comatus (Shaggy Mane) are often found in disturbed soils, such as lawns or roadside ditches, where organic matter is plentiful. By identifying these preferred habitats, foragers can strategically search for specific species based on the season and environmental conditions.

Temperature fluctuations also influence mushroom growth patterns in South Florida. While the region's temperatures remain relatively warm year-round, cooler nights during the wet season can stimulate fruiting in certain species. For instance, the Termitomyces species, associated with termite mounds, often appear after heavy rains and cooler evenings. In contrast, extreme heat during the dry season can inhibit fungal activity, making it less likely to find mushrooms unless conditions are unusually moist. Monitoring local weather patterns and understanding how temperature affects fungal life cycles can enhance foraging success and appreciation of South Florida's mycological diversity.

Finally, human activity and land use shape the distribution of wild mushrooms in South Florida. Urban areas with parks, gardens, and mulched landscapes can support species like the Stropharia rugosoannulata (Wine Cap Mushroom), which thrives in wood chip beds. However, foraging in these areas requires caution, as mushrooms may be exposed to pollutants or pesticides. Natural preserves and state parks, such as Everglades National Park or Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park, offer safer and more biodiverse foraging grounds. By respecting seasonal patterns, habitat preferences, and conservation guidelines, enthusiasts can sustainably explore and appreciate the wild mushrooms that grow in South Florida's unique ecosystems.

Are Poisonous Morel Mushrooms Found in Michigan? A Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

Ecosystem Roles: Explore how wild mushrooms contribute to South Florida’s biodiversity

South Florida's unique climate and ecosystems support a variety of wild mushrooms that play critical roles in maintaining biodiversity. One of the primary functions of these fungi is decomposition. Mushrooms like the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) and Ink Cap (Coprinus comatus) break down organic matter such as fallen trees, leaves, and dead plants. This process recycles nutrients back into the soil, enriching it and supporting the growth of other plant species. Without these decomposers, South Florida’s forests and wetlands would accumulate dead material, hindering nutrient cycling and ecosystem health.

Beyond decomposition, wild mushrooms in South Florida act as symbiotic partners through mycorrhizal relationships. Species like the Amanita genus form mutualistic associations with trees, including native palms and hardwoods. In these relationships, the fungi provide trees with essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, while the trees supply the fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This symbiosis enhances the resilience of South Florida’s forests, particularly in nutrient-poor soils, and supports the growth of diverse plant species, which in turn provide habitat for wildlife.

Mushrooms also contribute to soil structure and stability, particularly in South Florida’s wetlands and coastal ecosystems. Fungi like the Mycelium networks bind soil particles together, reducing erosion and improving water retention. This is especially important in areas prone to heavy rainfall and flooding, where soil stability is critical for preventing habitat loss. Additionally, these fungal networks create microhabitats for smaller organisms, such as bacteria and invertebrates, further enhancing biodiversity.

Another vital role of wild mushrooms is their function as a food source for various wildlife species. Mushrooms like the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) and Lactarius species are consumed by insects, rodents, and even larger animals like deer. By providing nutrition to these organisms, mushrooms indirectly support predators higher up the food chain, contributing to the overall balance of South Florida’s ecosystems. Furthermore, some mushrooms are pollinated by insects, fostering interactions that benefit both the fungi and their pollinators.

Finally, wild mushrooms in South Florida serve as indicators of ecosystem health. Species like the Turkey Tail (Trametes versicolor) and Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) are sensitive to environmental changes, such as pollution or habitat disturbance. Their presence or absence can signal the overall condition of an ecosystem, making them valuable tools for conservationists monitoring South Florida’s unique habitats. Protecting these fungi and their habitats is essential for preserving the region’s biodiversity and ecological integrity.

In summary, wild mushrooms in South Florida are not just fascinating organisms but also key players in maintaining ecosystem functions. From nutrient cycling and soil stabilization to supporting food webs and indicating environmental health, their roles are diverse and indispensable. Understanding and conserving these fungi is crucial for sustaining South Florida’s rich biodiversity in the face of environmental challenges.

Mushrooms Thriving in Damp Environments: Exploring Wetland Fungi Varieties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common wild mushrooms in South Florida include the Field Mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), the Toxic Green Amanita (*Amanita citrina*), the Ink Cap Mushroom (*Coprinus comatus*), and the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*).

Yes, several poisonous mushrooms grow in South Florida, such as the Deadly Amanita (*Amanita ocreata*), the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), and the Jack-O-Lantern Mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*). Always consult an expert before consuming wild mushrooms.

While foraging is possible, it is risky due to the presence of toxic species. Edible varieties like the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) and Chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*) may be found, but proper identification is crucial to avoid poisoning.

The best time to find wild mushrooms in South Florida is during the wet season, typically from June to October, when rainfall and humidity create ideal growing conditions.

Safely identifying wild mushrooms requires a field guide, a local mycology expert, or a mushroom foraging class. Avoid relying solely on online images, as many species look similar but have vastly different properties.