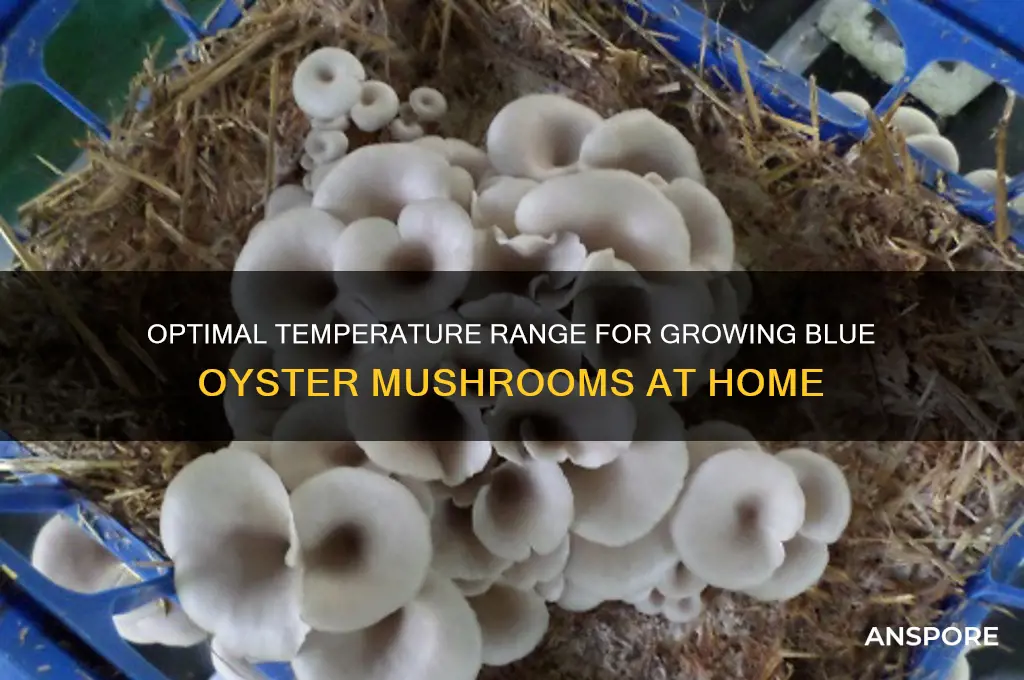

Blue oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are a popular variety of edible fungi known for their vibrant color and robust flavor. These mushrooms thrive in specific temperature ranges, which are crucial for their growth and development. Typically, blue oyster mushrooms grow best in temperatures between 60°F and 75°F (15°C to 24°C), with the optimal range being around 65°F to 70°F (18°C to 21°C). Temperatures below 50°F (10°C) can slow their growth, while temperatures above 80°F (27°C) may inhibit fruiting or cause stress to the mycelium. Maintaining consistent humidity and proper ventilation alongside the right temperature is essential for successful cultivation. Understanding these temperature requirements is key to maximizing yields and ensuring healthy, vibrant blue oyster mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Optimal Growth Temperature | 65–75°F (18–24°C) |

| Minimum Growth Temperature | 55°F (13°C) |

| Maximum Growth Temperature | 85°F (29°C) |

| Spawn Run Phase | 60–75°F (15–24°C) |

| Fruiting Phase | 55–75°F (13–24°C) |

| Temperature Tolerance | Sensitive to temperatures above 85°F (29°C) and below 50°F (10°C) |

| Humidity Requirement | 60–80% during fruiting |

| Temperature Fluctuation Tolerance | Minimal; consistent temperatures preferred |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal Temperature Range: 60-75°F for blue oyster mushroom growth and fruiting

- Spawn Run Phase: Requires 70-75°F for mycelium colonization and healthy development

- Fruiting Phase: Lower temps, 55-65°F, trigger mushroom pinning and growth

- Temperature Fluctuations: Avoid extremes; consistent temps prevent stress and contamination risks

- Cold Shock Method: Brief 35-40°F exposure can induce fruiting in mature mycelium

Optimal Temperature Range: 60-75°F for blue oyster mushroom growth and fruiting

Blue oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) thrive within a specific temperature window, and the range of 60–75°F (15–24°C) is where their growth and fruiting potential peak. This range is not arbitrary; it mirrors the cool, shaded environments these mushrooms naturally inhabit, such as decaying wood in temperate forests. Within this zone, mycelium colonizes substrate efficiently, and fruiting bodies develop robustly, ensuring higher yields and healthier mushrooms. Deviating from this range can stunt growth or prevent fruiting altogether, making temperature control a critical factor for cultivators.

To harness this optimal range effectively, cultivators should monitor temperature consistently, especially during the fruiting stage. Fluctuations outside 60–75°F, even briefly, can stress the mycelium or trigger abnormal fruiting. For instance, temperatures below 60°F slow metabolic processes, delaying growth, while temperatures above 75°F may cause the mushrooms to dry out or develop poorly. Using thermometers or digital sensors in grow rooms or fruiting chambers ensures stability. For small-scale growers, placing cultivation bags or trays in a temperature-controlled space, like a basement or insulated shed, can suffice.

The 60–75°F range also influences the timing and quality of fruiting. At the lower end (60–65°F), fruiting bodies tend to grow larger but more slowly, ideal for cultivators prioritizing size over speed. At the higher end (70–75°F), mushrooms fruit faster but may be smaller, suitable for quicker harvest cycles. Adjusting temperature within this range allows growers to tailor their cultivation to specific goals. For example, a commercial grower might opt for higher temperatures to maximize turnover, while a hobbyist might prefer slower growth for larger, more impressive specimens.

Practical tips for maintaining this range include using heating mats or space heaters in cooler environments and ensuring proper ventilation or air conditioning in warmer settings. For outdoor growers, timing cultivation to coincide with cooler seasons (spring or fall) can naturally align with the optimal range. Additionally, insulating grow spaces with foam boards or thermal blankets can buffer against external temperature swings. By prioritizing this narrow but powerful temperature window, cultivators can unlock the full potential of blue oyster mushrooms, achieving consistent, high-quality yields.

Pregnancy and Garlic Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Best Avoided?

You may want to see also

Spawn Run Phase: Requires 70-75°F for mycelium colonization and healthy development

Blue oyster mushrooms, like all fungi, are highly sensitive to environmental conditions, and temperature plays a pivotal role in their growth cycle. During the spawn run phase, the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—colonizes the substrate, laying the foundation for future fruiting. This critical stage demands precision, particularly in temperature control, to ensure robust and healthy development. Maintaining a temperature range of 70-75°F (21-24°C) is essential, as it mimics the mushroom’s natural habitat and optimizes metabolic processes. Deviating from this range can stunt growth, invite contaminants, or delay colonization, underscoring the importance of consistent monitoring and control.

Achieving the ideal temperature during the spawn run phase requires both attention to detail and practical strategies. For small-scale growers, using a thermostat-controlled incubator or a well-insulated grow room can help maintain stability. Larger operations might employ heating mats or air conditioners to regulate temperature fluctuations. It’s crucial to avoid sudden temperature spikes or drops, as these can stress the mycelium. For instance, placing the spawn near windows or external walls without insulation can expose it to drafts or temperature swings, hindering colonization. Regularly calibrating temperature sensors and using backup power sources for heating/cooling systems are proactive measures to prevent failures.

Comparatively, the spawn run phase is akin to the foundation of a building—if it’s weak, the entire structure suffers. Just as a builder ensures a solid base, a mushroom cultivator must prioritize this stage. While other phases, like fruiting, may demand different temperature ranges (typically 55-65°F), the spawn run’s 70-75°F requirement is non-negotiable. This distinction highlights the unique needs of each growth stage and the necessity of tailoring conditions accordingly. Ignoring this specificity can lead to poor yields or complete crop failure, making temperature control a cornerstone of successful cultivation.

For those new to mushroom cultivation, mastering the spawn run phase can seem daunting, but it’s a skill honed through practice and observation. Start by selecting a high-quality spawn and a suitable substrate, such as straw or sawdust, properly pasteurized to eliminate competitors. Monitor the colonization process daily, noting any signs of contamination or uneven growth. If the mycelium appears sluggish or discolored, reassess the temperature and humidity levels immediately. Patience is key; full colonization can take 2-4 weeks, depending on conditions. By maintaining the 70-75°F range and addressing issues promptly, even novice growers can achieve thriving mycelium networks ready for the next phase.

In conclusion, the spawn run phase is a make-or-break period in blue oyster mushroom cultivation, with temperature control as its linchpin. The 70-75°F range is not arbitrary but a scientifically backed requirement for mycelium colonization and health. By understanding its significance, employing practical strategies, and learning from comparative insights, growers can navigate this stage with confidence. Whether cultivating for personal use or commercial purposes, mastering this phase ensures a strong foundation for abundant harvests, proving that precision in temperature is the key to fungal success.

Creamy Comfort: The Versatile Magic of Condensed Mushroom Soup

You may want to see also

Fruiting Phase: Lower temps, 55-65°F, trigger mushroom pinning and growth

Blue oyster mushrooms, like many fungi, have a distinct fruiting phase that is highly temperature-sensitive. During this critical stage, lowering the ambient temperature to between 55°F and 65°F acts as a biological cue, signaling the mycelium to initiate pinning—the formation of tiny mushroom primordia. This temperature range mimics the cooler conditions of autumn, a natural trigger for fruiting in the wild. For cultivators, maintaining this precise window is essential; temperatures above 65°F can delay or inhibit fruiting, while those below 55°F may slow growth excessively.

To effectively manage this phase, cultivators should monitor both air and substrate temperatures. A digital thermometer with a probe placed near the growing mushrooms ensures accuracy. If using a grow tent or fruiting chamber, consider adding a small fan to circulate air and prevent temperature stratification. For those without controlled environments, fruiting during cooler seasons or in naturally cooler spaces (e.g., basements) can be advantageous. However, avoid sudden temperature fluctuations, as these can stress the mycelium and reduce yields.

The science behind this temperature sensitivity lies in the mushroom’s metabolic processes. Cooler temperatures slow down the mycelium’s vegetative growth, redirecting energy toward reproductive structures—the mushrooms themselves. This shift is a survival mechanism, ensuring spores are released before harsh winter conditions set in. Cultivators can exploit this natural behavior by strategically timing temperature drops after the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate. For example, if using a grow bag, introduce cooler temperatures 7–10 days after colonization is complete to encourage pinning.

Practical tips for success include gradual temperature adjustments rather than abrupt changes. If transitioning from a warmer incubation phase (typically 70–75°F), lower the temperature by 2–3°F per day until the target range is reached. Humidity levels should also be increased to 85–95% during this phase to support mushroom development. Misting the growing area 2–3 times daily or using a humidifier can help maintain optimal conditions. Finally, ensure adequate fresh air exchange to prevent CO₂ buildup, which can stunt growth even at ideal temperatures.

In summary, the fruiting phase of blue oyster mushrooms is a delicate dance with temperature. By maintaining 55–65°F, cultivators mimic the mushroom’s natural environment, triggering pinning and robust growth. Attention to detail—monitoring temperatures, adjusting gradually, and managing humidity—transforms this scientific principle into a practical cultivation strategy. Master this phase, and you’ll unlock consistent, bountiful harvests of these versatile mushrooms.

Magic Mushrooms: Potential Risks and Long-Term Effects on the Brain

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Temperature Fluctuations: Avoid extremes; consistent temps prevent stress and contamination risks

Blue oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) thrive in a temperature range of 55°F to 75°F (13°C to 24°C), with the sweet spot for fruiting around 60°F to 65°F (15°C to 18°C). However, maintaining this range isn’t just about hitting the numbers—it’s about consistency. Fluctuations beyond 5°F (3°C) in either direction can stress the mycelium, stunting growth and weakening its defenses against contaminants. For instance, a sudden drop to 50°F (10°C) or spike to 80°F (27°C) can halt pin formation or invite mold, even if the average temperature remains within the ideal range.

To prevent this, monitor your growing environment with a digital thermometer and hygrometer, ensuring they’re placed near the substrate, not just in the room. If using a grow tent or incubator, set the thermostat to maintain a steady 62°F (17°C) and avoid placing the setup near drafts, heaters, or windows. For outdoor growers, consider insulating containers with foam boards or moving them to a shaded area during midday heat spikes. Consistency isn’t just a preference for blue oysters—it’s a survival requirement.

A common mistake is assuming temperature control ends after colonization. During fruiting, mycelium is particularly vulnerable to stress, as energy shifts from vegetative growth to mushroom production. Even a 24-hour exposure to 85°F (29°C) can cause abortive pins or elongated, deformed stems. Conversely, temperatures below 50°F (10°C) slow metabolism, leaving the substrate susceptible to competing fungi like *Trichoderma*. The takeaway? Treat temperature as a non-negotiable variable, not a flexible guideline.

For those using ambient conditions, timing is key. Start fruiting in early spring or late fall when temperatures naturally hover around 60°F (15°C). If growing indoors, simulate this by adjusting your grow space seasonally. For example, move your setup to a cooler basement in summer or use a space heater with a thermostat in winter. Remember, blue oysters evolved in temperate forests, where seasonal shifts are gradual—mimic this stability, and you’ll reap the rewards.

Finally, consider the role of humidity in conjunction with temperature. While 60-70% relative humidity is ideal, its effectiveness depends on stable temps. High humidity at 80°F (27°C) encourages bacterial growth, while low humidity at 50°F (10°C) dries the substrate, starving the mycelium. Think of temperature as the foundation and humidity as the mortar—both must be consistent for the structure to hold. By prioritizing temperature stability, you’re not just growing mushrooms—you’re creating an environment where they can’t help but flourish.

Selling Mushrooms to Colorado Restaurants: Legalities, Opportunities, and Tips

You may want to see also

Cold Shock Method: Brief 35-40°F exposure can induce fruiting in mature mycelium

Blue oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) typically thrive in temperatures between 55°F and 75°F during their vegetative growth phase. However, a lesser-known technique, the Cold Shock Method, leverages a brief exposure to temperatures between 35°F and 40°F to trigger fruiting in mature mycelium. This method mimics the natural environmental cues that signal the transition from mycelial growth to mushroom production. By understanding and applying this technique, cultivators can manipulate the mushroom’s life cycle to optimize yields and timing.

The Cold Shock Method is particularly effective for mature mycelium that has fully colonized its substrate but has not yet initiated fruiting. To implement this technique, place the fully colonized substrate (such as straw or sawdust) in a refrigerator or cold room maintained at 35°F to 40°F for 24 to 48 hours. This sudden drop in temperature simulates the onset of winter, a natural trigger for blue oysters to produce fruit bodies. After the cold exposure, return the substrate to the optimal fruiting conditions of 60°F to 65°F with high humidity (85-95%) and adequate airflow. Within 5 to 10 days, primordial mushrooms should begin to form, followed by full fruiting bodies.

While the Cold Shock Method is straightforward, it requires precision and caution. Exposing the mycelium to temperatures below 35°F or extending the cold period beyond 48 hours risks damaging the mycelium or causing it to enter dormancy. Additionally, this method is most effective for mycelium that has reached full maturity; applying it too early may yield poor results. Cultivators should monitor the substrate’s colonization progress and ensure it is fully white and healthy before initiating the cold shock.

Comparatively, traditional fruiting methods rely on gradual environmental changes, such as reducing temperature and increasing humidity over time. The Cold Shock Method, however, offers a faster and more controlled approach, making it ideal for growers seeking to synchronize fruiting or overcome stubborn mycelium. Its efficiency lies in its ability to bypass the gradual acclimation process, directly stimulating the mycelium’s fruiting response.

In practice, the Cold Shock Method is a valuable tool for both small-scale and commercial growers. For instance, a home cultivator with a slow-fruiting batch can use this technique to expedite mushroom production. Similarly, commercial operations can employ it to align fruiting cycles with market demands. By mastering this method, growers can enhance their control over the cultivation process, ensuring consistent and timely yields of blue oyster mushrooms.

Drying Honey Mushrooms: A Simple Preservation Guide for Foragers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Blue oyster mushrooms thrive in temperatures between 60°F and 75°F (15°C and 24°C). This range promotes optimal mycelium growth and fruiting.

While blue oyster mushrooms can tolerate temperatures as low as 50°F (10°C), growth will be significantly slower, and fruiting may be delayed or inhibited.

Temperatures above 75°F (24°C) can stress the mycelium, leading to reduced growth, smaller fruiting bodies, or even the death of the mushroom culture.

During the fruiting stage, blue oyster mushrooms prefer slightly cooler temperatures, ideally between 55°F and 65°F (13°C and 18°C), to encourage robust pin formation and mushroom development.