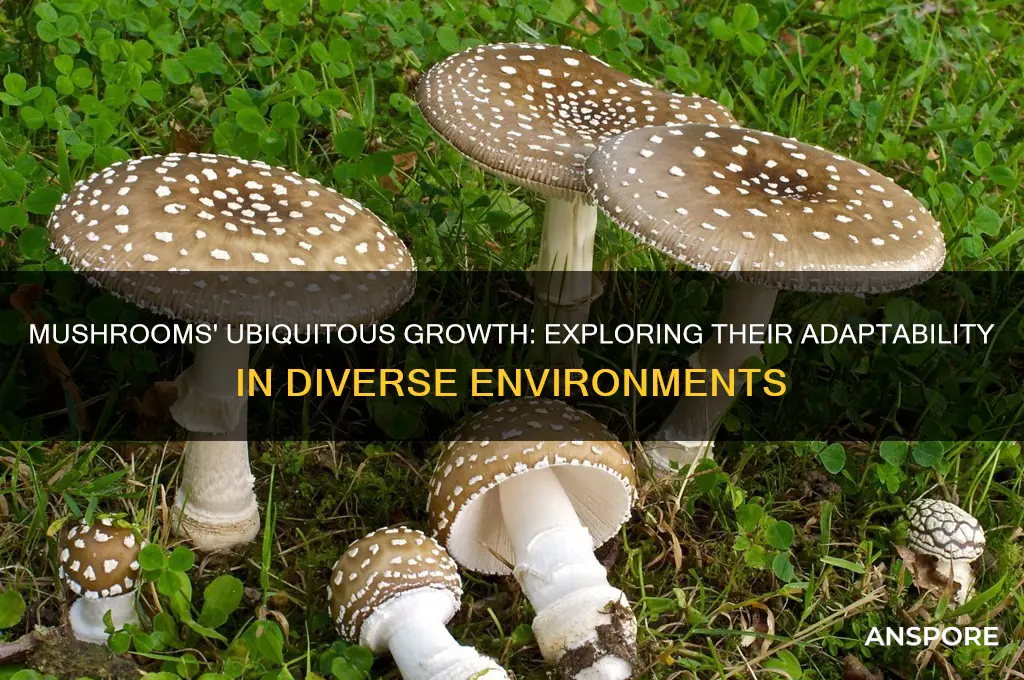

Mushrooms are remarkably adaptable organisms that can thrive in a wide variety of environments due to their unique biological characteristics and ecological roles. Unlike plants, which rely on photosynthesis, mushrooms are fungi that obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, allowing them to grow in low-light or dark conditions, such as forests, caves, and even urban areas. Their ability to break down dead plant and animal material makes them essential decomposers in ecosystems, recycling nutrients back into the environment. Additionally, mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with plants through mycorrhizal networks, enhancing nutrient uptake and resilience in challenging habitats. Their lightweight spores can travel vast distances via wind, water, or animals, enabling colonization of diverse environments, from arid deserts to damp basements. This combination of adaptability, ecological function, and efficient dispersal mechanisms explains why mushrooms can seemingly grow everywhere.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores | Mushrooms produce lightweight, wind-dispersed spores that can travel long distances, allowing them to colonize diverse environments. |

| Substrate Adaptability | They can grow on a wide range of organic materials, including wood, soil, dung, and even decaying matter, due to their saprotrophic nature. |

| Moisture Tolerance | Mushrooms thrive in moist environments, as they require water for spore germination and growth, but some species can also tolerate drier conditions. |

| Temperature Range | They can grow in various temperature ranges, from cold temperate forests to tropical regions, with some species adapted to extreme temperatures. |

| pH Tolerance | Mushrooms can grow in soils with different pH levels, from acidic to alkaline, depending on the species. |

| Shade Tolerance | Many mushroom species prefer shaded environments, as direct sunlight can dry out their fruiting bodies, but some can tolerate partial sunlight. |

| Symbiotic Relationships | Some mushrooms form mutualistic relationships with plants (mycorrhiza) or insects, which can enhance their growth and distribution. |

| Rapid Growth | Mushrooms can grow quickly under favorable conditions, allowing them to colonize new areas rapidly. |

| Decomposition Ability | As decomposers, mushrooms break down complex organic matter, recycling nutrients and creating suitable habitats for themselves. |

| Resilience | They can survive in harsh conditions, such as drought or pollution, by forming resistant structures like sclerotia or by remaining dormant as spores. |

| Global Distribution | Mushrooms are found on every continent, including extreme environments like deserts and polar regions, due to their adaptability and diverse species. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal Moisture Conditions: Mushrooms thrive in damp environments, absorbing water for growth and spore dispersal

- Adaptable Substrates: They grow on soil, wood, or organic matter, utilizing diverse nutrient sources

- Wide Temperature Tolerance: Mushrooms survive in various climates, from cold forests to tropical regions

- Spores Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals spread spores globally, aiding colonization

- Minimal Light Requirements: Mushrooms don’t need sunlight, relying on organic matter for energy

Optimal Moisture Conditions: Mushrooms thrive in damp environments, absorbing water for growth and spore dispersal

Mushrooms are nature's moisture meters, flourishing in environments where dampness prevails. Their ability to absorb water directly through their mycelium and fruiting bodies is a key factor in their ubiquitous presence. Unlike plants, which rely on roots to draw water from the soil, mushrooms have a more direct and efficient system. This unique adaptation allows them to thrive in places where other organisms might struggle, from the dense, humid forests to the damp corners of your basement. Understanding this relationship between mushrooms and moisture is crucial for both mycologists and enthusiasts alike.

Consider the ideal conditions for mushroom cultivation. In controlled environments, such as indoor farms, humidity levels are meticulously maintained between 85% and 95%. This range mimics the natural habitats where mushrooms naturally occur, ensuring optimal growth and spore dispersal. For home growers, achieving this level of humidity can be as simple as using a humidifier or regularly misting the growing area. However, it’s not just about adding water; proper ventilation is equally important to prevent the buildup of excess moisture, which can lead to mold or other contaminants. Balancing these factors creates a microclimate that mushrooms find irresistible.

In the wild, mushrooms often appear after rainfall, a phenomenon that highlights their dependence on water. Rain not only provides the necessary moisture but also helps disperse spores, which are carried by water droplets to new locations. This natural process explains why mushrooms can suddenly sprout in seemingly random places, from decaying logs to grassy lawns. For foragers, this means timing is everything—knowing when and where to look after a rain shower can yield a bountiful harvest. However, it’s essential to identify species accurately, as not all mushrooms are safe to consume.

The role of moisture in mushroom growth extends beyond mere hydration; it’s integral to their life cycle. Water acts as a medium for nutrient absorption and spore release, making damp environments not just favorable but essential. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are known to grow on wet straw or wood chips, where moisture levels are consistently high. In contrast, morels often appear in spring when the soil is still cool and damp from melting snow. These examples illustrate how different species have evolved to exploit specific moisture conditions, ensuring their survival across diverse ecosystems.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast, from sustainable agriculture to ecological restoration. By manipulating moisture levels, farmers can cultivate mushrooms on agricultural waste, turning byproducts into valuable food sources. Similarly, understanding moisture requirements can aid in conservation efforts, such as reintroducing native mushroom species to degraded habitats. For the everyday enthusiast, this means creating mushroom-friendly spaces in your garden or home by maintaining damp, shaded areas with organic matter. Whether you’re a grower, forager, or simply curious, recognizing the critical role of moisture in mushroom life opens up a world of possibilities.

Cream of Mushroom in Chicken Noodle Soup: A Flavorful Twist?

You may want to see also

Adaptable Substrates: They grow on soil, wood, or organic matter, utilizing diverse nutrient sources

Mushrooms thrive in environments as varied as lush forests, decaying logs, and even urban compost heaps, thanks to their ability to adapt to diverse substrates. Unlike plants, which rely on sunlight for energy, mushrooms are heterotrophs, obtaining nutrients by breaking down organic matter. This adaptability allows them to colonize soil, wood, and virtually any organic material, making them one of nature’s most versatile decomposers. Whether it’s the delicate oyster mushroom growing on dead trees or the resilient shiitake flourishing in sawdust, their substrate flexibility is a key to their ubiquity.

Consider the process of cultivating mushrooms at home. For instance, oyster mushrooms can be grown on straw, coffee grounds, or cardboard, while shiitakes prefer hardwood sawdust or logs. The substrate choice dictates the mushroom’s growth rate and yield. To maximize success, sterilize the substrate to eliminate competing organisms, then inoculate it with spawn. Maintain humidity levels between 70-90% and temperatures around 65-75°F (18-24°C) for optimal growth. This hands-on approach highlights how mushrooms exploit available resources, turning waste into food or ecosystem services.

From an ecological perspective, mushrooms’ substrate adaptability plays a critical role in nutrient cycling. In forests, they decompose fallen trees, returning essential elements like nitrogen and phosphorus to the soil. In urban settings, they break down organic waste, reducing landfill contributions. For example, mycelium—the vegetative part of a fungus—can degrade pollutants like oil and plastics, a process known as mycoremediation. This dual role as decomposer and cleaner underscores their importance in both natural and human-altered environments.

Comparatively, mushrooms’ substrate versatility contrasts sharply with most plants, which require specific soil conditions and sunlight. While a tomato plant struggles without fertile soil and six hours of sunlight, mushrooms flourish in darkness, feeding on cellulose, lignin, or even animal matter. This ability to utilize hard-to-digest materials gives them a competitive edge in nutrient-poor environments. For gardeners, incorporating mushroom compost into soil can improve structure and fertility, showcasing their practical value beyond food production.

In conclusion, mushrooms’ adaptability to substrates—soil, wood, or organic matter—is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Whether you’re a home grower experimenting with coffee grounds or an ecologist studying forest ecosystems, understanding this trait unlocks their potential. By harnessing their ability to thrive on diverse materials, we can cultivate food, remediate waste, and appreciate their role in sustaining life. Their substrate flexibility isn’t just a survival strategy—it’s a blueprint for resilience in a changing world.

Are Maggots in Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Wide Temperature Tolerance: Mushrooms survive in various climates, from cold forests to tropical regions

Mushrooms thrive across a staggering temperature range, from the frosty floors of boreal forests to the sweltering humidity of tropical rainforests. This adaptability isn't just luck; it's a survival strategy honed over millennia. Their secret lies in their cellular structure and metabolic flexibility. Unlike plants, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and rely on absorbing nutrients from their environment. This means they don't need sunlight for energy, allowing them to flourish in shaded, cooler areas. Furthermore, their cell walls, composed of chitin, provide structural support and protection against extreme temperatures.

Some species, like the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), can grow in temperatures as low as 4°C (39°F) and as high as 30°C (86°F). This wide tolerance enables them to colonize diverse habitats, from the chilly understory of coniferous forests to the warm, decaying logs of tropical jungles.

Consider the practical implications for cultivation. If you're growing mushrooms at home, understanding their temperature preferences is crucial. For cold-loving varieties like *P. ostreatus*, maintain a consistent temperature between 15°C and 20°C (59°F–68°F) for optimal growth. Tropical species, such as the lion's mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), prefer slightly warmer conditions, around 22°C–26°C (72°F–79°F). Avoid sudden temperature fluctuations, as these can stress the mycelium and hinder fruiting. Use a thermometer to monitor conditions, and consider a heating mat or cooling fan to regulate temperature in extreme climates.

The ability of mushrooms to tolerate such a broad temperature range also makes them resilient in the face of climate change. As global temperatures rise, many plant species struggle to adapt, but mushrooms' flexibility gives them an edge. For instance, the shiitake mushroom (*Lentinula edodes*) can grow in both temperate and subtropical regions, making it a reliable crop for farmers in varying climates. This adaptability not only ensures their survival but also highlights their potential as a sustainable food source in a changing world.

Finally, let’s compare mushrooms to other fungi. While yeasts and molds also exhibit temperature tolerance, mushrooms stand out due to their complex fruiting bodies and ability to form symbiotic relationships with plants. This duality—surviving independently or in partnership—amplifies their resilience. For example, mycorrhizal mushrooms like the chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) thrive in both cold and warm soils by partnering with tree roots, which provide stability and nutrients. This symbiotic strategy further broadens their temperature tolerance, showcasing the intricate ways mushrooms dominate diverse ecosystems.

In essence, mushrooms' wide temperature tolerance is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Whether you're a home grower, a farmer, or an ecologist, understanding this trait unlocks their potential in cultivation, conservation, and even climate adaptation. By harnessing their resilience, we can cultivate mushrooms sustainably and appreciate their role in ecosystems worldwide.

Enhance Your Mushroom Dishes: Top Spices for Flavorful Creations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals spread spores globally, aiding colonization

Mushrooms thrive in diverse environments, from dense forests to urban backyards, thanks in large part to the ingenious dispersal mechanisms of their spores. Unlike seeds, which rely on size and structure for survival, spores are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in staggering quantities—a single mushroom can release billions in a day. This abundance ensures that even if most spores fail to land in suitable conditions, enough will find fertile ground to sustain the species. The key to their success lies in how they travel: wind, water, and animals act as unwitting couriers, carrying spores across continents and ecosystems.

Consider the role of wind, the most far-reaching of these mechanisms. Mushroom spores are often equipped with structures like gills or pores that optimize their release into air currents. Once airborne, they can remain suspended for days, drifting hundreds of miles before settling. For instance, spores from the common *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane mushroom) have been detected in air samples far from their source, demonstrating wind’s efficiency in dispersal. To maximize this natural process, gardeners and mycologists can strategically place mushroom beds in open areas, ensuring spores catch prevailing winds. However, caution is advised in urban settings, as excessive spore dispersal can trigger allergies in sensitive individuals.

Water, though less discussed, plays a vital role in spore dispersal, particularly for species near rivers, lakes, or coastal areas. Spores of aquatic mushrooms, like those in the genus *Psathyrella*, are often hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces until they reach new habitats. Raindrops can also dislodge spores from mushroom caps, splashing them onto nearby soil or into streams. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms near water bodies, ensuring proper drainage is critical—excess moisture can lead to mold or bacterial contamination, undermining growth. A practical tip: use raised beds or perforated containers to balance hydration and aeration.

Animals, from insects to mammals, contribute significantly to spore dispersal, often without realizing it. Flies, beetles, and slugs are drawn to mushrooms for food or shelter, inadvertently picking up spores on their bodies and depositing them elsewhere. Larger animals, like deer or rodents, may carry spores on their fur after brushing against mushroom patches. To harness this mechanism, consider planting mushrooms near wildlife trails or creating habitats that attract spore-carrying creatures. However, be mindful of over-reliance on animals—overpopulation of pests can damage crops. A balanced approach, such as companion planting with pest-repelling herbs, can mitigate risks.

In conclusion, the global presence of mushrooms is a testament to the sophistication of spore dispersal mechanisms. By understanding and leveraging wind, water, and animal vectors, enthusiasts can enhance mushroom cultivation while minimizing drawbacks. Whether you’re a gardener, researcher, or simply curious, recognizing these processes offers practical insights into why mushrooms seem to grow everywhere—and how to encourage their growth responsibly.

Discovering Canned Cream of Mushroom Soup: Uses, Ingredients, and Tips

You may want to see also

Minimal Light Requirements: Mushrooms don’t need sunlight, relying on organic matter for energy

Mushrooms thrive in environments where sunlight is scarce or absent, a trait that sets them apart from most plants. Unlike their photosynthetic counterparts, mushrooms don’t rely on light for energy. Instead, they decompose organic matter—dead leaves, wood, or soil—to fuel their growth. This adaptability allows them to flourish in dark forests, underground caves, and even urban basements, making them one of nature’s most versatile organisms.

Consider the process: mushrooms secrete enzymes that break down complex organic materials into simpler compounds, which they then absorb for nourishment. This efficiency means they can grow in places where sunlight is minimal or nonexistent. For example, oyster mushrooms often colonize decaying logs in dense woodlands, while shiitakes prefer the shaded understory of hardwood forests. Even in artificial settings, like indoor farms, mushrooms require only controlled humidity and a substrate rich in organic matter—no sunlight necessary.

This light-independent growth has practical implications for cultivation. Home growers can cultivate mushrooms in dark corners of their homes, using kits that provide pre-inoculated substrates like straw or sawdust. The key is maintaining proper moisture levels and temperature, typically between 60°F and 75°F (15°C and 24°C). For instance, a beginner might start with a grow-your-own kit, placing it in a dim pantry or closet and misting it daily to simulate a forest floor environment.

Comparatively, plants demand specific light spectrums and durations, often requiring artificial lighting in indoor settings. Mushrooms, however, are undemanding in this regard, making them ideal for spaces where natural light is limited. This trait also explains their prevalence in ecosystems with dense canopies or subterranean habitats, where competition for light is fierce. While plants struggle in such conditions, mushrooms quietly decompose and recycle nutrients, playing a vital role in ecological balance.

In essence, mushrooms’ minimal light requirements are a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By bypassing the need for sunlight, they access untapped niches, ensuring their survival across diverse environments. Whether in a sunlit meadow or a pitch-black cave, mushrooms remind us that life finds a way—often in the shadows.

Exploring the Myth: Can You Orgasm While on Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms are fungi that thrive in diverse environments due to their ability to decompose organic matter, tolerate a wide range of temperatures and humidity levels, and reproduce via spores that can travel long distances.

Mushrooms are highly adaptable because they don’t require sunlight for energy, relying instead on decomposing organic material. This allows them to grow in dark, damp places like forests, caves, and even urban areas.

Yes, mushrooms can grow in unexpected places if conditions are right. They only need moisture, organic material (like dust or wood), and a suitable temperature. This is why they can appear on walls, in bathrooms, or even on carpets.

![Boomer Shroomer Inflatable Monotub Kit, Mushroom Growing Kit Includes a Drain Port, Plugs & Filters, Removeable Liner [Patent No: US 11,871,706 B2]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61uwAyfkpfL._AC_UL320_.jpg)