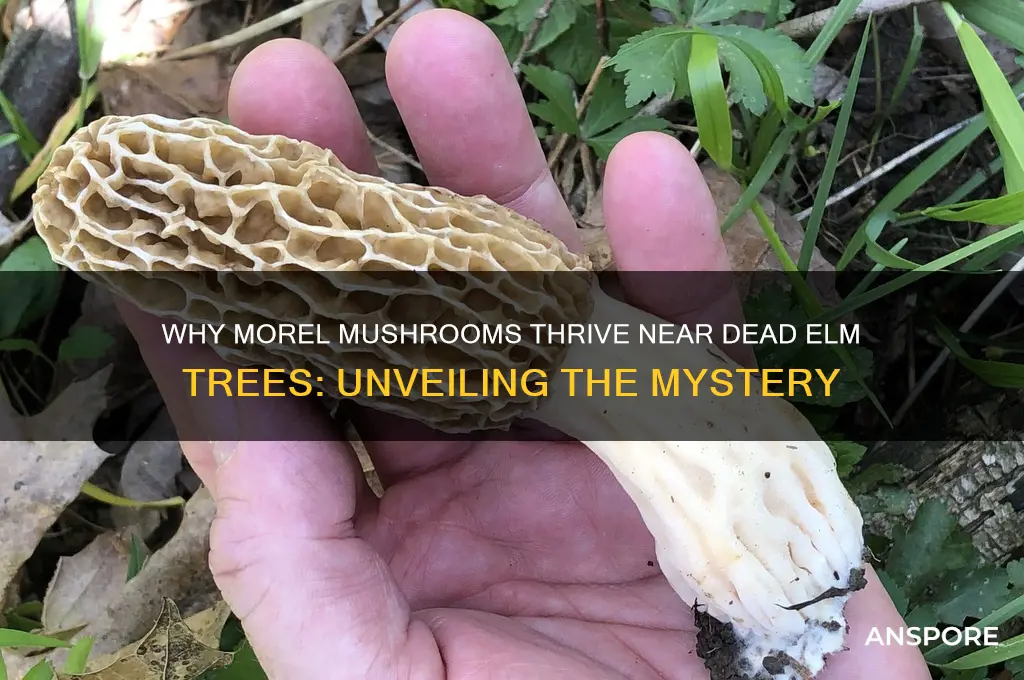

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, often form a fascinating symbiotic relationship with dead or dying elm trees. This phenomenon occurs because morels are saprotrophic fungi, meaning they derive nutrients from decomposing organic matter. Elm trees, when they die, provide an ideal substrate rich in cellulose and lignin, which morels are particularly adept at breaking down. Additionally, the mycelium of morels may have previously formed a mutualistic relationship with the elm tree’s roots, aiding in nutrient exchange while the tree was alive. As the tree declines, the fungi shift their role to decomposers, fruiting as morels to disperse spores and continue their life cycle. This intricate ecological interaction highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems and explains why morel hunters often find success near dead elm trees.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Elm tree decomposition process

The decomposition of elm trees is a complex and fascinating process that creates the ideal environment for morel mushrooms to thrive. When an elm tree dies, whether from disease, old age, or external factors, its once-vibrant structure begins a gradual breakdown, returning nutrients to the ecosystem. This process is primarily driven by a combination of physical, chemical, and biological factors. Initially, the tree’s bark may start to peel or crack, exposing the inner wood to the elements and opportunistic organisms. Moisture from rain or humidity penetrates the exposed areas, softening the wood and creating entry points for decomposers. This marks the beginning of the elm tree’s transformation into a nutrient-rich substrate.

As decomposition progresses, fungi and bacteria play a pivotal role in breaking down the tree’s lignin and cellulose, the primary components of its woody tissue. Fungi, in particular, secrete enzymes that degrade these tough materials, converting them into simpler organic compounds. This stage is crucial for morel mushrooms, as they form symbiotic relationships with the fungi already at work. The decaying wood becomes a source of nutrients and a stable structure for fungal mycelium to grow, which eventually supports the development of morel fruiting bodies. Simultaneously, insects and other invertebrates bore into the wood, accelerating fragmentation and creating additional pathways for microbial activity.

The chemical changes during elm tree decomposition are equally important. As the wood breaks down, organic acids and other byproducts are released, altering the soil pH and nutrient composition around the tree. This creates a microenvironment that favors specific fungal species, including those associated with morels. The gradual release of nutrients from the decomposing tree also enriches the surrounding soil, providing the essential elements morels need to grow. Over time, the once-solid elm tree becomes a spongy, nutrient-dense mass that serves as both food and habitat for a variety of organisms.

Physical factors, such as temperature and moisture, further influence the decomposition process. Morel mushrooms typically appear in spring when temperatures are mild and moisture levels are high, conditions that also accelerate the breakdown of elm wood. The combination of these factors ensures that the decomposition process is in full swing when morels are ready to fruit. Additionally, the presence of dead elm trees in open, well-drained areas—common habitats for morels—allows for optimal air circulation and sunlight penetration, which support both decomposition and mushroom growth.

In the final stages of decomposition, the elm tree’s structure becomes increasingly fragmented, eventually blending into the forest floor as humus. By this point, morel mushrooms have already completed their life cycle, releasing spores to colonize new areas. The entire process highlights the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems, where the death of one organism, like an elm tree, creates opportunities for others, such as morel mushrooms, to flourish. Understanding this decomposition process not only explains why morels grow by dead elm trees but also underscores the importance of natural decay in sustaining biodiversity.

Mastering Cubensis Cultivation: Techniques for Growing Larger Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal relationships with elms

Morel mushrooms often appear near dead or dying elm trees due to the intricate mycorrhizal relationships these fungi form with elms. Mycorrhizae are symbiotic associations between fungi and plant roots, where the fungus helps the tree absorb nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen from the soil, while the tree provides carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. Elms, being deciduous trees with extensive root systems, are particularly conducive to forming these relationships with morel fungi. When an elm tree dies, the mycelium of the morel fungus, which has been living in symbiosis with the tree, is no longer supported by the tree’s carbohydrates. This triggers the fungus to fruit, producing the morel mushrooms as a means to disperse spores and ensure survival.

The mycorrhizal relationship between morels and elms is specific and mutually beneficial under healthy conditions. Morel fungi, such as *Morchella* species, are ectomycorrhizal fungi, meaning they form a sheath around the tree’s roots without penetrating the root cells. This association enhances the elm’s ability to uptake water and nutrients, particularly in nutrient-poor soils. In return, the fungus receives sugars and other organic compounds from the tree. This partnership is crucial for the health and growth of both organisms, but it becomes particularly noticeable when the tree declines or dies, as the fungus shifts its energy toward reproduction, resulting in the visible fruiting bodies of morels.

Dead or stressed elm trees provide an ideal environment for morel mushrooms to grow because the breakdown of the tree’s root system releases nutrients into the soil, which the fungus can utilize. Additionally, the absence of competition from a living tree allows the fungus to allocate more resources to mushroom production. Elm trees, when healthy, may not always produce morels because the fungus is focused on the symbiotic relationship rather than fruiting. However, when the tree dies, the fungus responds to the loss of its partner by producing mushrooms to ensure its genetic continuity.

Understanding this mycorrhizal relationship is key to comprehending why morels are often found near dead elms. The fungus relies on the tree for survival, but it also has mechanisms to persist when the tree dies. This adaptability highlights the resilience of mycorrhizal fungi and their ability to thrive in changing environments. For foragers, this knowledge is invaluable, as it helps predict where morels might appear, particularly in areas with a history of elm decline, such as regions affected by Dutch elm disease.

In summary, the mycorrhizal relationship between morel fungi and elms is a delicate balance of mutualism and survival strategies. The fungus supports the tree’s nutrient uptake while receiving essential carbohydrates in return. When the elm dies, the fungus shifts its focus to reproduction, resulting in the appearance of morel mushrooms. This process not only explains why morels grow near dead elms but also underscores the importance of mycorrhizal associations in forest ecosystems. By studying these relationships, we gain insights into the complex interactions between fungi and trees, and how disturbances like tree death can trigger fungal fruiting.

Exploring the Natural Habitats of Psilocybe Cubensis Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Nutrient availability in dead wood

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, often thrive in specific environments, particularly near dead or dying elm trees. This phenomenon is closely tied to the nutrient availability in dead wood, which creates an ideal substrate for morel mycelium to grow and fruit. Dead wood, especially from elm trees, undergoes a decomposition process that releases a wealth of nutrients essential for fungal growth. As the wood breaks down, complex organic compounds are transformed into simpler forms that morels can readily absorb. This process is facilitated by the symbiotic relationship between fungi and decomposer organisms like bacteria and other microorganisms, which work together to recycle nutrients from the wood.

One of the key nutrients available in dead wood is cellulose, a structural component of plant cell walls. While morels cannot directly break down cellulose, the decomposer organisms in the wood do this work, releasing sugars and other carbohydrates that morels can utilize. Additionally, dead wood is rich in lignin, a complex polymer that provides structural support in trees. Lignin decomposition is a slower process, but it eventually releases organic compounds that contribute to the nutrient pool available to morels. This gradual breakdown ensures a steady supply of nutrients over time, supporting the long-term growth of morel mycelium.

Mineral nutrients are another critical component of dead wood that supports morel growth. As the wood decomposes, minerals like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are released from the tree’s tissues. These minerals are essential for fungal metabolism and the development of fruiting bodies. Elm trees, in particular, are known to accumulate certain minerals in their wood, which may explain why morels are frequently found near dead elms. The availability of these minerals in dead wood creates a fertile environment that meets the nutritional needs of morels, promoting their growth and fruiting.

The pH level of the decomposing wood also plays a role in nutrient availability for morels. Dead wood typically creates a slightly acidic environment, which is favorable for many fungal species, including morels. This acidity enhances the solubility of certain minerals, making them more accessible to the fungi. Furthermore, the porous structure of decomposing wood allows for better water retention and aeration, both of which are crucial for nutrient uptake by morel mycelium. This combination of factors ensures that the nutrients in dead wood are not only abundant but also easily absorbed by the fungi.

Lastly, the presence of dead wood provides a physical substrate for morel mycelium to colonize and expand. As the mycelium grows through the wood, it can efficiently extract nutrients from the surrounding environment. This close association with dead wood allows morels to outcompete other fungi and establish a dominant presence in the ecosystem. The nutrient-rich conditions in dead elm wood, therefore, create a microhabitat that is particularly conducive to morel growth, explaining why these mushrooms are often found in such locations. Understanding the nutrient dynamics of dead wood highlights the intricate relationship between morels and their environment, shedding light on the factors that drive their distribution and abundance.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Ideal Habitats and Growing Conditions Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.48

Moisture retention near decaying trees

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, often thrive in specific environmental conditions, particularly near decaying trees like elms. One of the key factors contributing to their growth in these areas is moisture retention near decaying trees. Decaying wood acts as a natural sponge, absorbing and holding water from rainfall or irrigation. This moisture is slowly released into the surrounding soil, creating a consistently damp environment that morels require for their life cycle. Unlike many other fungi, morels are highly sensitive to drying out, making this steady moisture supply critical for their development.

The process of decay in trees, driven by fungi and bacteria, breaks down complex wood structures into simpler organic matter. This decomposition generates a porous substrate that enhances water retention. As the tree’s bark and inner layers deteriorate, they create air pockets and channels that trap moisture, preventing it from quickly evaporating or draining away. This microenvironment ensures that the soil around the decaying tree remains moist even during drier periods, providing an ideal habitat for morel mycelium to grow and fruit.

In addition to retaining moisture, decaying trees contribute to the overall soil structure and composition, further supporting moisture retention. As the wood breaks down, it enriches the soil with organic matter, improving its water-holding capacity. Organic matter acts like a sponge, absorbing water and releasing it slowly over time. This not only benefits morels but also fosters a healthy ecosystem of microorganisms and other fungi that contribute to nutrient cycling and soil health.

The root systems of decaying trees also play a role in moisture retention. Even after a tree dies, its roots remain in the soil for years, continuing to hold water and prevent erosion. These roots create pathways for water to penetrate deeper into the soil, ensuring that moisture is available at various depths where morel mycelium may be growing. Additionally, the shade provided by the standing dead tree or its remnants reduces direct sunlight, minimizing soil surface evaporation and maintaining a cooler, more humid environment.

For foragers and cultivators, understanding the importance of moisture retention near decaying trees can inform strategies for finding or growing morels. Planting or preserving dead and decaying trees in suitable areas can create favorable conditions for morel growth. Mulching around these trees with wood chips or leaves can further enhance moisture retention and mimic the natural environment morels prefer. By focusing on maintaining consistent soil moisture, enthusiasts can increase their chances of a successful morel harvest.

In summary, moisture retention near decaying trees is a critical factor in the growth of morel mushrooms. The unique properties of decaying wood, combined with the lingering effects of root systems and the enrichment of soil with organic matter, create an environment that supports the specific needs of morels. For anyone interested in cultivating or foraging these elusive fungi, prioritizing moisture management around decaying trees is a key step toward success.

Mastering Psilocybe Cubensis Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Growing Guide

You may want to see also

pH changes in elm-rich soil

Morel mushrooms have a fascinating relationship with dead elm trees, and one of the key factors contributing to this association is the pH changes that occur in elm-rich soil. Elm trees, when alive, play a significant role in shaping the soil chemistry around them. Elms are known to thrive in slightly acidic to neutral soils, typically with a pH range of 6.0 to 7.5. However, as an elm tree dies and begins to decompose, the soil pH undergoes notable transformations that create an ideal environment for morel mushrooms to grow.

The decomposition of elm wood introduces organic acids into the soil, which tend to lower the pH, making the soil more acidic. This process is facilitated by fungi and bacteria that break down the lignin and cellulose in the dead wood. Morel mushrooms, being saprotrophic fungi, are particularly adapted to thrive in these acidic conditions. The optimal pH range for morel growth is between 6.0 and 7.0, which aligns well with the pH shift observed in decomposing elm-rich soil. This acidity not only supports morel mycelium development but also suppresses competing organisms, giving morels a competitive advantage.

Another critical aspect of pH changes in elm-rich soil is the release of nutrients during decomposition. As the elm tree breaks down, essential minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium are released into the soil. These nutrients become more available to morels in the slightly acidic environment, promoting their growth. Additionally, the acidic conditions enhance the solubility of certain nutrients, making them easier for morel mycelium to absorb. This nutrient-rich, acidic soil creates a fertile ground for morels to establish and fruit successfully.

It is also important to note that the pH changes in elm-rich soil are not instantaneous but occur gradually over time. The initial stages of decomposition may see a more rapid drop in pH as organic acids are released, but as decomposition progresses, the pH may stabilize or even slightly increase due to the buffering capacity of the soil. This gradual process allows morel mycelium to adapt and colonize the area effectively. Gardeners and foragers often mimic these conditions by adding elm wood chips or sawdust to their soil to encourage morel growth, emphasizing the importance of pH manipulation in cultivating these prized mushrooms.

In summary, the pH changes in elm-rich soil are a critical factor in understanding why morel mushrooms grow by dead elm trees. The decomposition of elm wood lowers the soil pH, creating an acidic environment that morels favor. This acidity, combined with the release of essential nutrients, provides an optimal habitat for morel growth. By studying these pH dynamics, enthusiasts can better replicate the natural conditions that support morel fruiting, whether in the wild or in cultivated settings.

Mastering Beech Mushroom Cultivation: Simple Steps for Abundant Harvests

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Morel mushrooms thrive in environments with decaying wood, and dead elm trees provide the ideal substrate. The decomposing wood releases nutrients that morels need to grow, while the tree’s roots create a network that supports fungal growth.

While morels are not exclusive to elm trees, they have a symbiotic relationship with certain tree species, including elms. The fungi help break down the dead wood, and in return, they absorb nutrients from the decaying matter, making elm trees a common spot for morel growth.

Morels can grow in various locations, but dead or dying hardwood trees, including elms, ash, and oak, are prime spots. They prefer disturbed soil and decaying wood, so areas with fallen trees, wildfires, or logging activity are also common habitats.