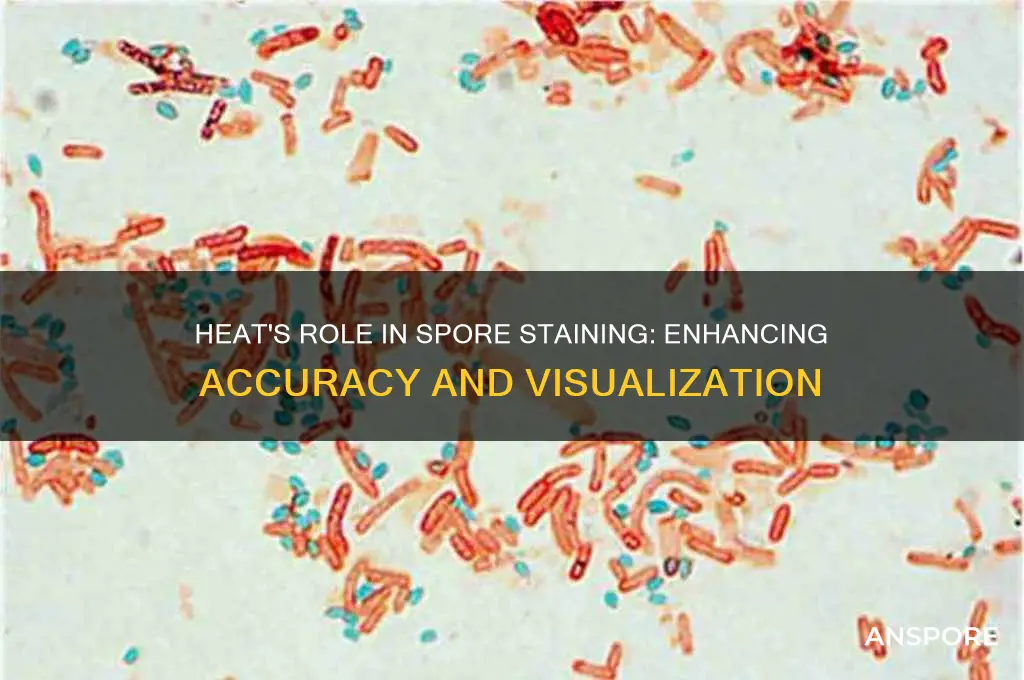

Heat is a critical component in spore staining procedures, particularly in methods like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, as it facilitates the penetration of dyes into the highly resistant spore wall. Spores are encased in a durable outer layer composed of materials like keratin, which makes them impermeable to most staining agents under normal conditions. Applying heat during the staining process helps to temporarily increase the permeability of the spore wall, allowing the primary dye (typically malachite green) to enter and bind effectively. Additionally, heat aids in fixing the dye to the spore, ensuring a more permanent and intense coloration. Without this heat treatment, spores would often remain unstained or weakly stained, making them difficult to distinguish from vegetative bacterial cells under a microscope. Thus, heat is essential for achieving accurate and reliable results in spore staining.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose of Heat | Fixes primary stain (usually malachite green) to the spore's tough outer coat, ensuring it doesn't wash away during decolorization. |

| Mechanism | Heat increases the permeability of the spore's outer layers, allowing the stain to penetrate more effectively. |

| Decolorization Resistance | Spores are naturally resistant to decolorization due to their thick, impermeable coats. Heat helps overcome this resistance by softening the coat. |

| Selective Staining | Heat treatment differentiates spores from vegetative cells, as vegetative cells are more easily decolorized. |

| Durability of Stain | Heat fixation makes the malachite green stain more permanent within the spore, ensuring it remains visible even after rigorous washing. |

| Time Efficiency | Heat application reduces the overall staining time compared to relying solely on prolonged incubation at room temperature. |

| Safety | Heat treatment can help kill any vegetative cells present, reducing the risk of contamination during the staining process. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Heat fixes spores to slide, preventing washing away during staining process

- Enhances dye penetration through spore’s tough, impermeable cell wall

- Activates primary stain (e.g., malachite green) for better spore coloration

- Differentiates spores from vegetative cells by resisting decolorization

- Ensures accurate identification of spore-forming bacteria in microscopy

Heat fixes spores to slide, preventing washing away during staining process

Heat application is a critical step in spore staining, serving as the anchor that secures spores to the slide. Without this fixation, spores—being highly resilient and hydrophobic—would easily detach during the rigorous washing and staining processes. The heat essentially acts as a biological glue, adhering the spores firmly to the glass surface. This ensures that the subsequent staining reagents can interact effectively with the spore structures, providing clear and accurate results.

Consider the practical steps involved in this process. After preparing a smear of the bacterial sample on a clean slide, the slide is gently heated using a flame or a specialized slide warmer. The ideal temperature range is typically between 50°C to 70°C, applied for 1–2 minutes. Overheating can damage the spores, while insufficient heat may fail to fix them properly. A common technique is to pass the slide through a bunsen burner flame 2–3 times, ensuring even heating without scorching. This simple yet precise step is the foundation for successful staining.

The mechanism behind heat fixation is both physical and chemical. Heat causes the proteins and lipids in the spore’s outer layers to denature and adhere to the slide’s surface. Additionally, it removes moisture from the smear, further enhancing adhesion. This dual action prevents spores from being washed away during the decolorization step, where harsh chemicals like acetone or alcohol are used. Without fixation, the staining process would be inconsistent, leading to false negatives or unclear results, particularly in samples with low spore counts.

A comparative analysis highlights the importance of heat fixation. In other staining techniques, such as simple Gram staining, mechanical fixation (e.g., air drying) may suffice. However, spores’ robust endospore structure demands a more robust method. Heat fixation not only secures the spores but also prepares them for the intense chemical treatments that follow. For instance, in the Schaeffer-Fulton method, heat fixation ensures that the spores remain intact during the malachite green staining and subsequent decolorization, allowing for vivid green spores against a pink vegetative cell background.

In conclusion, heat fixation is not merely a preparatory step but a cornerstone of spore staining. It transforms a fragile smear into a stable, analyzable specimen. For microbiologists and lab technicians, mastering this technique ensures reliable identification of spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species. By adhering to precise temperature and timing guidelines, practitioners can avoid common pitfalls like washed-away spores or heat-damaged samples, ultimately achieving accurate and reproducible results.

Ozone's Power: Effectively Eliminating Mold Spores in Your Environment

You may want to see also

Enhances dye penetration through spore’s tough, impermeable cell wall

Spores present a unique challenge in microbiology due to their exceptionally resilient cell walls, which are designed to withstand extreme conditions. These walls are composed of multiple layers, including a thick layer of peptidoglycan and an outer proteinaceous coat, making them highly impermeable to most staining agents. This inherent toughness necessitates a method that can effectively breach these barriers to allow dyes to penetrate and visualize the spores. Heat plays a pivotal role in this process by altering the physical properties of the cell wall, making it more receptive to staining.

The application of heat during spore staining, often referred to as the "heat fixation" step, serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it fixes the spores to the slide, preventing them from being washed away during subsequent steps. More critically, however, heat increases the fluidity of the cell wall’s lipid components and disrupts the hydrogen bonds within its structure. This temporary alteration creates microscopic channels or pores, facilitating the entry of dyes such as malachite green, which is commonly used in spore staining procedures. Without this heat-induced modification, the dye would struggle to penetrate the impermeable barrier, resulting in faint or incomplete staining.

Practical implementation of this technique involves heating the slide containing the bacterial smear over a flame or using a specialized heating device for 3–5 minutes. The temperature should be sufficient to generate steam but not so high as to char the sample or boil off the staining solution. For instance, in the traditional endospore staining method, the slide is gently heated while a drop of malachite green is applied, ensuring even distribution. This step is followed by a prolonged exposure (5–10 minutes) to allow the dye to thoroughly penetrate the heat-softened cell walls.

A comparative analysis highlights the effectiveness of heat in spore staining versus other methods. Chemical treatments, such as those using strong acids or bases, can also disrupt cell walls but often lead to spore damage or distortion. Mechanical methods, like sonication, are less controlled and may yield inconsistent results. Heat, on the other hand, provides a reliable and controlled approach that preserves spore morphology while enhancing dye penetration. This makes it the preferred method in standard microbiological protocols, particularly for differentiating spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*.

In conclusion, heat is indispensable in spore staining because it directly addresses the challenge posed by the spore’s tough, impermeable cell wall. By temporarily altering its structure, heat ensures that dyes can effectively penetrate and bind to the spore, enabling clear visualization under a microscope. This simple yet critical step underscores the importance of understanding the physical and chemical properties of microbial structures in laboratory techniques. For practitioners, mastering this process not only improves staining outcomes but also enhances the accuracy of microbiological analyses.

Mastering Spore: A Beginner's Guide to Evolving Your Creature

You may want to see also

Activates primary stain (e.g., malachite green) for better spore coloration

Heat is a critical component in spore staining, particularly when using primary stains like malachite green. The application of heat during the staining process serves a specific and essential purpose: it activates the primary stain, enhancing its ability to penetrate the spore’s tough outer coat and achieve better coloration. This activation is not merely a cosmetic enhancement but a fundamental step in ensuring accurate identification and differentiation of spores under microscopic examination.

From an analytical perspective, the spore wall is composed of a highly resistant layer called sporopollenin, which is impermeable to most stains at room temperature. Heat application, typically through a gentle steaming or warming process, increases the kinetic energy of the stain molecules, allowing them to more effectively diffuse through the spore wall. For instance, when malachite green is heated, its solubility and mobility increase, enabling it to bind more efficiently to the spore’s cellular components. This chemical interaction results in a vivid, uniform coloration that is crucial for clear visualization and analysis.

Instructively, the process of heat activation involves precise steps to ensure optimal results. After applying the primary stain (e.g., malachite green) to the spore sample, the slide is typically heated over a steam bath or a low-flame burner for 5–10 minutes. It’s important to maintain a consistent temperature, as excessive heat can damage the spores, while insufficient heat may result in poor staining. A practical tip is to monitor the slide closely, ensuring the stain does not dry out during heating. Once heated, the slide is allowed to cool before proceeding with the counterstaining step, such as safranin, to differentiate spores from other cellular elements.

Comparatively, heat activation of malachite green stands out when contrasted with staining techniques for less resilient microorganisms. For example, simple bacterial staining often relies on room-temperature incubation, as bacterial cell walls are more permeable. Spores, however, require this additional heat step due to their unique structural resilience. This distinction highlights the tailored approach needed for spore staining, emphasizing why heat is indispensable in this specific context.

Descriptively, the transformation of spore coloration post-heat activation is striking. Before heating, spores may appear faintly stained or unevenly colored, reflecting the stain’s inability to fully penetrate the spore wall. After heat application, the spores exhibit a deep, uniform green hue, a testament to the stain’s successful activation and binding. This enhanced coloration not only improves visual clarity but also aids in distinguishing spores from other debris or organisms in the sample, a critical factor in fields like microbiology and environmental science.

In conclusion, heat activation of primary stains like malachite green is a cornerstone of effective spore staining. By understanding the chemical and structural dynamics at play, practitioners can optimize this step to achieve superior results. Whether in a laboratory setting or field research, mastering this technique ensures accurate and reliable spore identification, underscoring the indispensable role of heat in this process.

Best Places to Purchase Morel Mushroom Spores for Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differentiates spores from vegetative cells by resisting decolorization

Heat is a critical component in spore staining, particularly during the decolorization step, because it enhances the differential staining of spores versus vegetative cells. When performing a spore stain, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, the application of heat fixes the primary stain (e.g., malachite green) to both spores and vegetative cells. However, the key distinction arises during decolorization. Vegetative cells, with their thinner cell walls, readily release the primary stain when exposed to water or alcohol, while spores, protected by their thick, impermeable coats, retain the stain. This resistance to decolorization is a defining characteristic of spores and allows for their clear differentiation under a microscope.

To achieve this differentiation effectively, the heat application step must be precise. Typically, the slide is heated by gently passing it through a flame 20–30 times or by using a steam source for 5–10 minutes. Overheating can damage the sample, while insufficient heat may result in incomplete fixation of the primary stain, leading to false negatives. The goal is to ensure the malachite green penetrates the spore’s durable exosporium, a process facilitated by heat. This step is particularly crucial when working with bacterial species like *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, where accurate spore identification is essential for diagnostic or research purposes.

From a practical standpoint, the decolorization step immediately following heat application is where the magic happens. After heating, the slide is treated with water or alcohol for 30–60 seconds. Here, the vegetative cells lose their green color, appearing colorless or faintly stained, while the spores remain a distinct green. This contrast is vital for microbiologists, as it allows for the enumeration and identification of spores in a mixed population. For instance, in food microbiology, distinguishing spores from vegetative cells helps assess the effectiveness of sterilization processes, ensuring food safety.

A comparative analysis highlights why heat is indispensable in this process. Without heat, the primary stain might not adequately penetrate the spore’s protective layers, leading to inconsistent results. Alternative methods, such as prolonged staining without heat, often fail to achieve the same level of differentiation. Heat acts as a catalyst, ensuring the stain binds irreversibly to the spore’s structure, while the vegetative cells remain susceptible to decolorization. This reliability makes heat-based spore staining the gold standard in microbiology laboratories.

In conclusion, the role of heat in spore staining is to create a clear distinction between spores and vegetative cells by ensuring spores resist decolorization. This process, rooted in the physical properties of spores, is both a scientific principle and a practical technique. By mastering the application of heat and understanding its effects, microbiologists can accurately identify and quantify spores, a critical skill in fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring. Proper execution of this step transforms a simple staining procedure into a powerful tool for microbial analysis.

Exploring Fungi Reproduction: Sexual, Asexual, or Both?

You may want to see also

Ensures accurate identification of spore-forming bacteria in microscopy

Heat is a critical step in spore staining, particularly when using the traditional Ziehl-Neelsen method, as it ensures the accurate identification of spore-forming bacteria under microscopy. This process, known as heat fixation, involves passing the stained slide through a flame 2-3 times or heating it on a hot plate at 80-100°C for 1-2 minutes. The primary purpose is to melt the bacterial cell wall’s wax-like components, allowing the primary stain (e.g., carbol fuchsin) to penetrate and bind irreversibly to the spore’s heat-resistant coat. Without this step, the stain may not adhere properly, leading to false negatives or misinterpretation of results.

Analyzing the mechanism reveals why heat is indispensable. Spores of bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* possess a thick, impermeable exosporium that resists most stains. Heat disrupts this barrier, enabling the primary stain to enter and mark the spore. Subsequent decolorization and counterstaining steps then highlight the spores distinctly against the vegetative cells. For instance, in a clinical sample, heat fixation ensures that spores appear as bright red or green bodies (depending on the stain used) against a blue or pink background, facilitating precise identification. Omitting heat could result in spores remaining unstained or weakly stained, potentially leading to misdiagnosis.

From a practical standpoint, mastering the heat fixation step requires attention to detail. Overheating can damage the sample, causing cell lysis or spore deformation, while insufficient heat may fail to achieve the desired permeability. A recommended technique is to use a Bunsen burner, passing the slide quickly through the flame 2-3 times to avoid overheating. Alternatively, a hot plate set at 80-100°C for 1-2 minutes provides more controlled heating. Always ensure the slide is dry before heating to prevent steam formation, which can disrupt the staining process.

Comparing heat fixation to alternative methods underscores its necessity. While some modern techniques, such as microwave-assisted staining, aim to reduce processing time, they often require specialized equipment and may not be as reliable for all bacterial species. Heat fixation remains the gold standard due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and consistent results across various spore-forming bacteria. For laboratories with limited resources, this traditional method ensures accurate identification without compromising quality.

In conclusion, heat is not merely a procedural step in spore staining but a cornerstone for accurate microscopic identification of spore-forming bacteria. By ensuring proper stain penetration, it distinguishes spores from vegetative cells, enabling precise diagnosis and research. Whether in a clinical, educational, or research setting, adhering to the correct heating protocol is essential for reliable results. Mastery of this technique empowers microbiologists to confidently identify spore-forming pathogens, contributing to effective disease management and scientific advancement.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Heat is necessary in spore staining to help fix the primary stain (e.g., malachite green) to the spore’s thick, impermeable cell wall, ensuring the spores retain the stain during subsequent decolorization steps.

If heat is not applied, the primary stain may not adequately penetrate the spore’s cell wall, leading to poor or incomplete staining, and the spores may not be visible or may wash out during decolorization.

Heat increases the permeability of the spore’s cell wall, allowing the primary stain (malachite green) to penetrate more effectively and bind firmly to the spore, ensuring it remains stained even after decolorization.

While some alternative methods exist, heat is the most reliable and efficient way to ensure proper staining of spores. Without heat, the staining process is less consistent and may yield unsatisfactory results.

The ideal temperature for heat application is around 80°C (176°F), and the duration is typically 5–10 minutes. This ensures the stain penetrates the spore’s cell wall without damaging the sample.