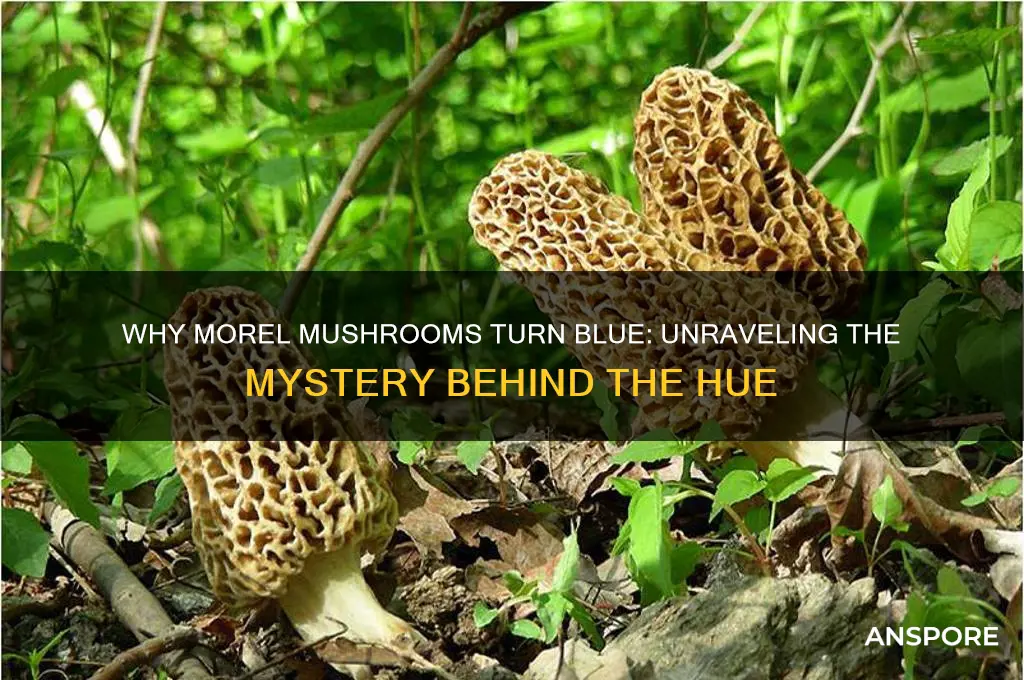

Morel mushrooms, prized for their unique flavor and texture, are often sought after by foragers and chefs alike. However, a curious phenomenon occurs when these mushrooms are damaged, bruised, or exposed to certain conditions: they turn blue. This color change is a natural reaction caused by the oxidation of chemicals within the mushroom, particularly a compound called hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF). While the blue hue might initially raise concerns, it is generally considered a harmless indicator of the mushroom’s freshness or handling rather than a sign of spoilage. Understanding why morels turn blue not only sheds light on their biology but also helps foragers and enthusiasts ensure they are harvesting and preparing these delicacies safely and effectively.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Oxidation Reaction: Exposure to air causes chemical changes, leading to blue discoloration in morel mushrooms

- Bruising Mechanism: Physical damage triggers enzymes, resulting in rapid blue coloration as a defense response

- Species Variation: Certain morel species naturally turn blue when cut, cooked, or handled

- Toxicity Indicator: Blueing may signal potential toxicity, though not all blue morels are poisonous

- Environmental Factors: Soil pH, moisture, and temperature can influence blueing in morel mushrooms

Oxidation Reaction: Exposure to air causes chemical changes, leading to blue discoloration in morel mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, sometimes exhibit a striking blue discoloration. This phenomenon, while not harmful, often raises concerns about edibility and quality. The culprit behind this color change is a simple yet fascinating chemical process: oxidation. When morels are exposed to air, their cellular structure undergoes a transformation, leading to the production of pigments responsible for the blue hue.

Understanding the Chemistry

Imagine slicing a morel mushroom and leaving it on a cutting board. Within minutes, the exposed flesh begins to darken, eventually turning a shade of blue-gray. This is oxidation in action. Similar to how a cut apple browns, morels contain enzymes and phenolic compounds that react with oxygen in the air. This reaction, known as enzymatic browning, results in the formation of melanin-like pigments, which are responsible for the blue discoloration. The intensity of the blue depends on factors like the mushroom's age, moisture content, and the duration of air exposure.

Young, freshly harvested morels are less likely to turn blue immediately, while older mushrooms or those with damaged caps may show rapid discoloration.

Practical Implications for Foragers

Foraging enthusiasts should understand that blueing in morels is primarily a cosmetic issue. While it might affect the mushroom's visual appeal, it doesn't necessarily indicate spoilage or toxicity. However, it's crucial to differentiate between natural blueing and other discoloration caused by bruising, insect damage, or decay. Always inspect morels thoroughly before consumption, discarding any with slimy textures, off odors, or unusual colors beyond the typical blueing.

As a general rule, if a morel smells pleasantly earthy and its flesh is firm, it's likely safe to eat, even if it has turned blue.

Minimizing Blueing: Tips for Preservation

To preserve the natural color of morels, minimize their exposure to air. After harvesting, store them in a breathable container like a paper bag or a loosely woven basket. Avoid airtight containers, as they can trap moisture and accelerate spoilage. For longer storage, consider drying or freezing morels. Drying removes moisture, halting the oxidation process, while freezing slows it down significantly. When preparing morels for cooking, cut or clean them just before use to minimize air contact. If blueing does occur during preparation, it can be partially masked by incorporating the mushrooms into sauces, soups, or dishes with darker ingredients.

Mushroom Allergies: Are They Rare or Common?

You may want to see also

Bruising Mechanism: Physical damage triggers enzymes, resulting in rapid blue coloration as a defense response

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their distinctive flavor and texture, occasionally exhibit a striking blue discoloration when handled or damaged. This phenomenon, far from random, is a precise biological response rooted in the mushroom’s defense mechanisms. When the delicate cellular structure of a morel is disrupted—whether by cutting, squeezing, or even insect predation—specific enzymes within the mushroom are activated. These enzymes catalyze a rapid chemical reaction, transforming naturally occurring compounds into a blue pigment. This process, akin to the browning of an apple when sliced, serves as a visual warning to potential threats and may also deter further damage by signaling toxicity or unpalatability.

To understand this bruising mechanism, consider the steps involved. First, physical damage breaches the mushroom’s cell walls, releasing enzymes stored in specialized compartments. These enzymes, typically inactive in undamaged tissue, immediately interact with polyphenol compounds present in the mushroom. The reaction produces a blue melanin-like pigment, which spreads quickly through the affected area. Foragers can observe this transformation within minutes, often starting at the point of injury and radiating outward. Notably, this response is not uniform across all morels; younger specimens or those with higher enzyme concentrations may exhibit more intense coloration.

While the blue discoloration might alarm novice foragers, it is not inherently a sign of spoilage or toxicity. However, caution is warranted. The enzymes involved in this process can sometimes alter the mushroom’s flavor profile, making bruised morels less desirable for culinary use. Additionally, the rapid blueing may indicate that the mushroom has been mishandled or is past its prime. For optimal quality, foragers should harvest morels gently, using a knife or scissors to minimize damage, and inspect them for pre-existing bruises before cooking. Storing morels in a single layer on a breathable surface, such as a paper towel, can also reduce the risk of accidental bruising.

Comparatively, the bruising mechanism of morels shares similarities with defense responses in other organisms, such as the blackening of potatoes when exposed to air. However, the speed and intensity of the blueing in morels are uniquely adapted to their environment. Unlike plants, which can rely on roots and stems for structural support, fungi like morels are more vulnerable to physical damage. Their rapid response to injury underscores the importance of this mechanism in their survival strategy. By studying this process, scientists gain insights into fungal biology and potential applications in biotechnology, such as developing natural pigments or antimicrobial agents.

In practical terms, understanding the bruising mechanism can enhance both foraging and culinary practices. For instance, chefs can use the blueing reaction as a freshness indicator, avoiding morels that show extensive discoloration. Foragers, meanwhile, can employ techniques to minimize damage, such as using mesh bags for collection to allow spores to disperse while protecting the mushrooms. While the blue coloration itself is not harmful, it serves as a reminder of the delicate nature of morels and the intricate defenses they employ to thrive in their ecosystems. By respecting these mechanisms, enthusiasts can enjoy morels sustainably while appreciating the marvels of fungal biology.

Are Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights and Facts

You may want to see also

Species Variation: Certain morel species naturally turn blue when cut, cooked, or handled

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers and chefs alike, exhibit a fascinating trait: some species naturally turn blue when disturbed. This phenomenon is not a sign of spoilage or toxicity but rather a characteristic tied to their unique chemistry. Species like *Morchella esculenta* and *Morchella angusticeps* are known to develop blue hues when cut, cooked, or handled, a reaction that has intrigued mycologists and enthusiasts for decades. Understanding this species-specific behavior is crucial for accurate identification and safe consumption.

The blueing reaction in morels is primarily attributed to the oxidation of certain compounds present in their fruiting bodies. When the mushroom’s cells are damaged—whether by slicing, bruising, or cooking—enzymes interact with polyphenols, triggering a chemical change that results in the blue coloration. This process is similar to the browning of apples or avocados when exposed to air. However, unlike those fruits, the blueing in morels is not a sign of degradation but rather a natural and harmless response. Foragers should note that this trait can vary even within the same species, depending on factors like age, environmental conditions, and genetic diversity.

To observe this phenomenon, simply slice a fresh morel in half and watch for color changes over a few minutes. If the mushroom turns blue, it’s likely one of the species known for this trait. This test can be particularly useful in distinguishing morels from false morels, which typically do not exhibit blueing. However, caution is advised: while blueing is a helpful indicator, it should not be the sole criterion for identification. Always cross-reference with other features like cap shape, stem structure, and habitat to ensure accuracy.

Practical tips for handling blueing morels include cooking them thoroughly, as heat accelerates the oxidation process and enhances the color change. This not only highlights their unique chemistry but also ensures any potential toxins are neutralized. Foraging guides often recommend blanching morels in water before cooking to remove debris and mild toxins, a step that can also intensify the blueing effect. While the blue color may fade during prolonged cooking, its presence during preparation is a reliable marker for certain species.

In conclusion, the natural blueing of specific morel species is a captivating example of fungal biology. By recognizing this trait, foragers can deepen their understanding of these mushrooms and make informed decisions in the field and kitchen. While not all morels turn blue, those that do offer a visual clue to their identity, enriching the foraging experience and ensuring a safer harvest. Always approach mushroom identification with care, combining multiple characteristics to avoid misidentification.

Mushroom Survival Guide: Edible, Poisonous, and Medicinal Varieties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Toxicity Indicator: Blueing may signal potential toxicity, though not all blue morels are poisonous

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their earthy flavor and meaty texture, occasionally exhibit a striking blue discoloration. While this phenomenon might spark curiosity, it also raises a critical question: is a blue morel safe to eat? The answer lies in understanding the complex relationship between blueing and toxicity.

Blueing in morels is primarily attributed to a chemical reaction between the mushroom's pigments and oxygen. This process, known as oxidation, can be triggered by various factors, including age, handling, and environmental conditions. Interestingly, some morel species, like the black morel (*Morchella elata*), are more prone to blueing than others.

It's crucial to emphasize that blueing itself isn't a definitive indicator of toxicity. While some poisonous mushrooms, like the false morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), can also turn blue, many edible morels exhibit this characteristic without posing any health risks. This nuance highlights the importance of species identification. Foraging guides and expert consultation are invaluable tools for accurately identifying morel species, ensuring you avoid potentially harmful lookalikes.

Remember, when in doubt, throw it out. Consuming even a small amount of a toxic mushroom can lead to severe illness or even death.

The blueing phenomenon serves as a reminder of the intricate chemistry within mushrooms. While it can be a potential red flag, it shouldn't be the sole criterion for determining edibility. Responsible foraging practices, including proper identification and thorough cooking, are paramount for a safe and enjoyable mushroom hunting experience.

Trademark Battle: 1-Up Mushroom Ownership

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Soil pH, moisture, and temperature can influence blueing in morel mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their earthy flavor and distinctive honeycomb caps, sometimes exhibit a striking blue discoloration. While this phenomenon can spark concern, it’s often a natural response to environmental conditions. Soil pH, moisture levels, and temperature play pivotal roles in triggering this blueing, each factor interacting with the mushroom’s biochemistry in unique ways. Understanding these relationships not only demystifies the discoloration but also empowers foragers to predict and interpret blueing in the wild.

Soil pH: The Chemical Catalyst

Soil pH acts as a silent orchestrator of blueing in morels. These fungi thrive in slightly acidic to neutral soils, typically with a pH range of 6.0 to 7.5. When soil pH deviates significantly—either becoming too acidic or alkaline—it can disrupt the mushroom’s cellular processes. Acidic soils, for instance, may increase the availability of certain metals like iron or aluminum, which can react with the mushroom’s pigments. This reaction often results in a blue hue, a visual cue that the mushroom is responding to its environment. Foragers should note that blueing in highly acidic soils (pH below 5.5) is more common, though not always indicative of toxicity. Testing soil pH with a portable kit can provide valuable context for interpreting blueing.

Moisture: The Hydration Equation

Moisture is another critical player in the blueing drama. Morels require consistent moisture to grow, but excessive rain or humidity can stress the fungus. When waterlogged, morels may absorb more minerals and compounds from the soil, including those that contribute to blueing. Conversely, drought conditions can also trigger discoloration as the mushroom struggles to maintain cellular integrity. Optimal moisture levels for morels fall between 50% and 70% soil saturation, with blueing more likely to occur outside this range. Foragers should observe not only the mushroom’s color but also the surrounding soil’s wetness to gauge the role of moisture in blueing.

Temperature: The Thermal Trigger

Temperature fluctuations can act as a stressor that accelerates blueing in morels. These fungi prefer cool to moderate temperatures, typically between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C). When temperatures rise above 75°F (24°C), metabolic processes within the mushroom can become erratic, leading to increased production of pigments that cause blueing. Similarly, sudden cold snaps can shock the fungus, prompting a defensive biochemical response. Foragers should consider recent weather patterns when encountering blue morels, as temperature extremes often correlate with discoloration. Tracking local climate data can enhance the ability to predict blueing based on thermal conditions.

Practical Tips for Foragers

To minimize blueing and ensure a safe harvest, foragers can take proactive steps. First, scout areas with stable environmental conditions—soils with a pH near neutrality, moderate moisture levels, and consistent temperatures. Second, avoid harvesting morels during or immediately after extreme weather events, as these periods heighten the likelihood of blueing. Finally, always inspect mushrooms for other signs of degradation, such as sliminess or off odors, as blueing alone is not a definitive indicator of edibility. By integrating knowledge of soil pH, moisture, and temperature, foragers can better interpret blueing and make informed decisions in the field.

In essence, blueing in morel mushrooms is a complex interplay of environmental factors, each leaving its mark on the fungus’s appearance. By understanding these dynamics, foragers can deepen their appreciation for these enigmatic mushrooms while ensuring a safer and more rewarding harvest.

Magic of OM: Extracting the Power of Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Morel mushrooms can turn blue when exposed to certain environmental factors, such as bruising, aging, or cooking. This color change is often due to oxidation or chemical reactions within the mushroom.

Generally, a blue morel is still safe to eat if it has turned blue due to bruising or cooking. However, if the blue color is accompanied by a foul odor or slimy texture, it may indicate spoilage, and the mushroom should be discarded.

No, the blue color in morel mushrooms is not typically a sign of toxicity. It is usually a natural reaction to handling, cooking, or aging. True toxic mushrooms, like false morels, have distinct characteristics unrelated to color changes.

While it’s difficult to completely prevent blueing, handling morels gently and cooking them promptly can minimize the color change. Storing them properly (e.g., in a breathable container in the refrigerator) can also help reduce oxidation.