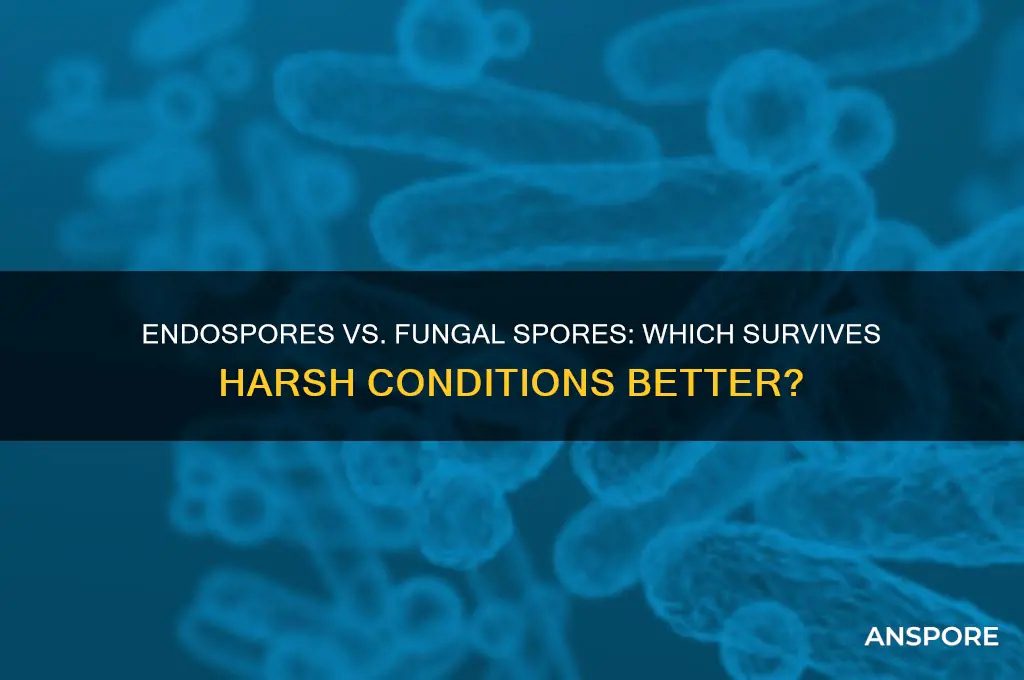

Endospores, produced by certain bacteria such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are renowned for their extraordinary resistance to extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. In contrast, fungal spores, while also highly resilient, generally exhibit lower resistance to such harsh environments. This disparity raises the question: are endospores more resistant than fungal spores? Understanding the structural and biochemical differences between these two types of spores is crucial to answering this question, as it sheds light on their survival strategies and implications in fields like microbiology, medicine, and environmental science.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heat Resistance | Endospores can survive temperatures up to 100°C for extended periods, often requiring autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes to be destroyed. Fungal spores are generally less heat-resistant, typically inactivated at temperatures between 60°C and 80°C. |

| Desiccation Resistance | Endospores can survive in dry conditions for decades or even centuries. Fungal spores are also highly desiccation-resistant but generally less so than endospores, surviving for years under favorable conditions. |

| Radiation Resistance | Endospores exhibit high resistance to UV radiation and ionizing radiation, often surviving doses that would kill most other organisms. Fungal spores are moderately resistant but less so than endospores. |

| Chemical Resistance | Endospores are highly resistant to disinfectants, including alcohols, quaternary ammonium compounds, and many other chemicals. Fungal spores are also resistant but can be more easily inactivated by certain chemicals compared to endospores. |

| Structural Protection | Endospores have a thick, multi-layered protective coat, including a spore coat and cortex, which provides extreme resistance. Fungal spores have a simpler structure with a cell wall that offers protection but is less robust than that of endospores. |

| Metabolic Activity | Endospores are metabolically dormant and do not actively repair damage, relying on their protective structure. Fungal spores can remain dormant but may retain some metabolic activity, which can aid in survival under certain conditions. |

| Environmental Persistence | Endospores can persist in harsh environments, including soil, water, and extreme conditions, for extended periods. Fungal spores are also widespread in the environment but generally less persistent in extreme conditions compared to endospores. |

| Germination Requirements | Endospores require specific conditions (e.g., nutrients, moisture) to germinate and return to vegetative growth. Fungal spores also require specific conditions but may germinate under a broader range of environmental triggers. |

| Biological Significance | Endospores are primarily formed by certain bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) as a survival mechanism. Fungal spores are produced by fungi for reproduction and dispersal, serving both survival and reproductive functions. |

| Overall Resistance | Endospores are generally considered more resistant than fungal spores across most environmental stressors, making them one of the most resilient biological structures known. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Heat Resistance Comparison: Endospores vs. fungal spores under extreme temperatures

- Chemical Tolerance: Which spore type withstands harsh chemicals better

- Radiation Survival: Effects of UV and gamma radiation on both spores

- Desiccation Endurance: How each spore type handles prolonged dryness

- Longevity in Environment: Survival duration of endospores vs. fungal spores

Heat Resistance Comparison: Endospores vs. fungal spores under extreme temperatures

Endospores, produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, are renowned for their extreme resistance to heat, capable of withstanding temperatures up to 100°C for hours or even autoclave conditions (121°C for 15–20 minutes). This resilience is attributed to their low water content, thick proteinaceous coats, and DNA-protecting mechanisms. Fungal spores, while also hardy, generally tolerate lower temperatures, typically surviving pasteurization (60–70°C) but succumbing to autoclaving. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores can survive 60°C for 30 minutes but are inactivated at 80°C within minutes. This stark difference highlights endospores’ superior heat resistance, making them a greater challenge in sterilization processes.

To compare heat resistance practically, consider a sterilization protocol for medical equipment. Endospores of *Bacillus stearothermophilus* are often used as biological indicators, requiring 121°C for 30 minutes to ensure inactivation. In contrast, fungal spores like *Trichoderma* are inactivated at 80°C for 10 minutes. This disparity underscores the need for higher temperatures or longer exposure times when targeting endospores. For home canning, boiling water (100°C) suffices to kill most fungal spores but may fail against endospores, necessitating pressure canning to achieve the higher temperatures required.

From an analytical perspective, the heat resistance of endospores and fungal spores can be explained by their structural differences. Endospores’ core contains dehydrated DNA and dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes the spore under heat stress. Fungal spores, while having robust cell walls, lack these protective compounds, rendering them more vulnerable. A study in *Journal of Applied Microbiology* found that *Clostridium botulinum* endospores survived 110°C for 90 minutes, whereas *Fusarium* fungal spores were inactivated after 20 minutes at the same temperature. This data reinforces the hierarchical resistance: endospores > fungal spores.

For industries like food preservation and healthcare, understanding this resistance is critical. A persuasive argument for investing in advanced sterilization techniques, such as steam sterilization or chemical disinfectants, lies in the endospores’ tenacity. While fungal spores pose risks in mold contamination, endospores, particularly those of pathogenic bacteria, can survive standard heat treatments, leading to foodborne illnesses or infections. For example, *Clostridium perfringens* endospores have caused outbreaks in inadequately heated foods, whereas *Penicillium* spores are typically controlled by mild heat treatments.

In conclusion, the heat resistance of endospores far exceeds that of fungal spores, necessitating tailored sterilization strategies. While fungal spores are effectively managed with pasteurization temperatures, endospores demand extreme heat or alternative methods like radiation or chemicals. This comparison underscores the importance of identifying the target organism in sterilization processes to ensure safety and efficacy. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or kitchen, recognizing the unique challenges posed by endospores is essential for preventing contamination and ensuring public health.

Bacterial Spores vs. Preformed Toxins: Understanding the Key Differences

You may want to see also

Chemical Tolerance: Which spore type withstands harsh chemicals better?

Endospores, produced by certain bacteria, are renowned for their resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. Fungal spores, while also hardy, often pale in comparison when exposed to harsh chemicals. This disparity raises a critical question: which spore type truly dominates in chemical tolerance?

Consider the application of disinfectants like bleach, a common household chemical. Endospores can withstand concentrations of up to 5% sodium hypochlorite for extended periods, a feat largely unmatched by fungal spores, which typically succumb at lower concentrations. This is due to the endospore’s multilayered protective coat, including a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid, which confers resistance to oxidizing agents. Fungal spores, though protected by a chitinous cell wall, lack this chemical buffer, making them more vulnerable to such agents.

To test this, a simple experiment can be conducted: expose *Bacillus subtilis* endospores and *Aspergillus niger* fungal spores to 10% bleach for 30 minutes. Observe that the endospores remain viable, while the fungal spores show significant reduction in germination rates. This demonstrates the endospore’s superior chemical tolerance, particularly against oxidizing and alkylating agents.

However, not all chemicals favor endospores. Fungal spores exhibit greater resistance to desiccation and certain organic solvents, such as ethanol, due to their chitin-based wall. For instance, fungal spores can survive 70% ethanol for hours, whereas endospores may require additional protective mechanisms to endure such exposure. This highlights a nuanced comparison: while endospores excel in resisting disinfectants, fungal spores have their own chemical strongholds.

In practical terms, understanding these differences is crucial for industries like food preservation and healthcare. For instance, sterilizing equipment in hospitals often involves chemicals like glutaraldehyde, which effectively targets fungal spores but may require higher concentrations or longer exposure times to eliminate endospores. Conversely, in food processing, fungal spores’ tolerance to ethanol-based sanitizers necessitates alternative methods, such as heat treatment, to ensure complete decontamination.

In conclusion, while endospores generally outperform fungal spores in chemical tolerance, particularly against disinfectants, the latter hold their ground in specific chemical environments. Tailoring decontamination strategies to the spore type ensures efficacy, whether in a laboratory, hospital, or food production facility. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical microbiology and practical application, offering a targeted approach to spore eradication.

Effective Mold Removal: Cleaning Clothes Exposed to Mold Spores

You may want to see also

Radiation Survival: Effects of UV and gamma radiation on both spores

Endospores and fungal spores are both renowned for their resilience, but their resistance to radiation varies significantly. When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, endospores, such as those produced by *Bacillus* species, exhibit remarkable tolerance. For instance, a dose of 1000 J/m² of UV-C radiation, which is lethal to most vegetative cells, barely affects endospores. This is due to their thick, multi-layered spore coat and the presence of DNA-protecting proteins like SASP (Small Acid-Soluble Sporoproteins). In contrast, fungal spores, like those of *Aspergillus niger*, are more susceptible to UV radiation, with many being inactivated by doses as low as 100 J/m². This disparity highlights the superior protective mechanisms of endospores against UV damage.

Gamma radiation, a high-energy ionizing radiation, presents a different challenge. Endospores again demonstrate exceptional resistance, surviving doses up to 10 kGy, which is orders of magnitude higher than what most fungal spores can withstand. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* endospores require doses exceeding 5 kGy for complete inactivation, whereas *Penicillium* spores are typically inactivated at around 1 kGy. This resistance is attributed to the endospores' low water content, compact DNA structure, and the presence of dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes the spore’s core. Fungal spores, despite having melanin—a pigment that can absorb radiation—lack these additional protective features, rendering them more vulnerable.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in industries like food preservation and medical sterilization. To ensure the elimination of both endospores and fungal spores, gamma radiation doses must be carefully calibrated. For instance, in food processing, a dose of 25 kGy is often used to target endospores, effectively eliminating fungal spores as well. However, this high dose can alter food quality, necessitating a balance between safety and preservation. In healthcare, understanding these differences is critical for sterilizing equipment, as fungal spores may be inactivated at lower doses, but endospores require more aggressive treatment.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both spore types have evolved mechanisms to withstand harsh environments, endospores are unequivocally more resistant to both UV and gamma radiation. This is not merely a matter of degree but a fundamental difference in their biological design. Fungal spores, though resilient, are outmatched by the endospores' specialized defenses. For researchers and practitioners, this underscores the importance of tailoring radiation protocols to the specific spore type, ensuring both safety and efficiency in applications ranging from agriculture to medicine.

Are All Mold Spores Dangerous? Uncovering the Truth About Mold Exposure

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Desiccation Endurance: How each spore type handles prolonged dryness

Endospores, produced by certain bacteria, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme environmental conditions, including prolonged desiccation. These structures can survive without water for decades, even centuries, by entering a state of metabolic dormancy. Their resistance to dryness is attributed to their multi-layered protective coats, low water content, and DNA-protecting proteins. For instance, studies have shown that *Bacillus subtilis* endospores can remain viable after being exposed to arid conditions for over 25 years, making them a benchmark for desiccation endurance.

Fungal spores, while also capable of surviving dry environments, generally exhibit lower desiccation resistance compared to endospores. Fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce spores with a higher water content and less robust cell walls, rendering them more susceptible to prolonged dryness. However, some fungal species, such as *Xeromyces bisporus*, have evolved mechanisms to tolerate desiccation, including accumulating sugars like trehalose, which act as cellular protectants. Despite these adaptations, fungal spores typically lose viability after a few years of desiccation, far shorter than endospores.

To compare the two, consider a practical scenario: storing spores for long-term preservation. Endospores require minimal preparation, often surviving in ambient conditions without additional protectants. Fungal spores, on the other hand, benefit from desiccation protocols that include cryopreservation or the addition of stabilizers like glycerol. For example, fungal spores stored at -80°C with 10% glycerol retain viability for up to 10 years, whereas endospores remain viable at room temperature for decades without intervention.

The key takeaway is that while both spore types can endure desiccation, endospores outclass fungal spores in longevity and resilience. This difference is critical in applications like biotechnology, where long-term storage of microbial cultures is essential. For researchers or practitioners, understanding these disparities ensures the selection of appropriate preservation methods, whether it’s relying on the innate robustness of endospores or implementing protective measures for fungal spores.

Understanding Spore Prints: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Longevity in Environment: Survival duration of endospores vs. fungal spores

Endospores, produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, are renowned for their extraordinary resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions for centuries. Fungal spores, while also durable, pale in comparison when it comes to longevity in the environment. A prime example is the 1995 discovery of viable *Bacillus* endospores in a 250-million-year-old salt crystal, contrasted with fungal spores that typically remain viable for decades, not millennia. This stark difference underscores the unparalleled survival capabilities of endospores.

To understand this disparity, consider the structural differences. Endospores possess a multilayered protective coat, including a thick spore cortex and a proteinaceous exosporium, which shields their DNA from desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. Fungal spores, though equipped with a robust cell wall, lack this level of fortification. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores can survive for 20–30 years in soil, but their survival is contingent on environmental factors like humidity and temperature, whereas endospores remain viable in conditions as harsh as outer space.

Practical implications of this longevity are significant. In healthcare, endospores of *Clostridioides difficile* can persist on hospital surfaces for up to 5 months, necessitating specialized disinfectants like bleach (5,000 ppm) for effective decontamination. Fungal spores, such as those of *Candida*, are less persistent but still pose challenges, surviving weeks on medical equipment. For environmental control, understanding these differences is crucial: while fungal spores may require periodic cleaning, endospores demand rigorous sterilization protocols, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both spores are adapted for survival, endospores are evolutionarily optimized for extreme durability. Fungal spores prioritize rapid dispersal and germination in favorable conditions, whereas endospores are designed to endure until conditions improve, even if that takes centuries. This distinction is vital for industries like food preservation, where endospores of *Bacillus cereus* can survive pasteurization (72°C), unlike most fungal spores, which are inactivated at this temperature.

In conclusion, the survival duration of endospores far exceeds that of fungal spores, making them the undisputed champions of environmental longevity. This knowledge is not merely academic; it informs practical strategies in healthcare, food safety, and environmental management. Whether you’re sterilizing medical equipment or preserving food, understanding these differences ensures effective control of microbial threats.

Effective Milky Spore Application: A Step-by-Step Guide for Lawn Grub Control

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, endospores are generally more resistant to extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals compared to fungal spores.

Endospores have a thick, multi-layered protective coat, low water content, and DNA repair mechanisms, which provide greater resistance to environmental stressors than the simpler structure of fungal spores.

While fungal spores are resilient, they are less capable of surviving extreme conditions like high temperatures or prolonged desiccation compared to endospores, which are among the most durable biological structures known.

No, endospores rely on their unique structure and metabolic dormancy for resistance, whereas fungal spores depend on their cell wall composition and ability to remain dormant, but to a lesser extent.

Endospores are more likely to survive in environments with extreme heat, radiation, or chemical exposure, while fungal spores are better adapted to moderate environmental challenges like soil or air.