Spore-forming bacteria are a unique group of microorganisms known for their ability to produce highly resistant endospores, which allow them to survive extreme environmental conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. A common question regarding these bacteria is whether they are classified as Gram-positive or Gram-negative. The answer lies in the structure of their cell walls: spore-forming bacteria are predominantly Gram-positive. This is because they lack the outer membrane characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria and instead possess a thick peptidoglycan layer, which retains the crystal violet stain during Gram staining. Notable examples of spore-forming Gram-positive bacteria include *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, which are widely studied for their ecological and medical significance. Understanding their Gram classification is essential for identifying and targeting these bacteria in various scientific and clinical contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Gram Staining | Most spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive. |

| Examples | Bacillus, Clostridium, Sporosarcina, Streptomyces. |

| Spore Location | Endospores (formed inside the cell). |

| Spore Function | Survival in harsh conditions (heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Cell Wall Structure | Thick peptidoglycan layer (typical of Gram-positive bacteria). |

| Exceptions | A few Gram-negative spore-formers exist (e.g., Sporomusa). |

| Relevance | Spore formation is primarily associated with Gram-positive bacteria. |

Explore related products

$80.75 $96.99

What You'll Learn

Spore Formation Mechanism

Spore-forming bacteria, primarily Gram-positive, employ a sophisticated survival mechanism to endure harsh environmental conditions. This process, known as sporulation, involves a series of intricate cellular changes that transform a vegetative cell into a highly resistant spore. Understanding the spore formation mechanism is crucial for fields like microbiology, food safety, and medicine, as it sheds light on bacterial resilience and potential control strategies.

Let’s delve into the key steps of this remarkable process.

Initiation: Sensing Stress and Triggering the Response

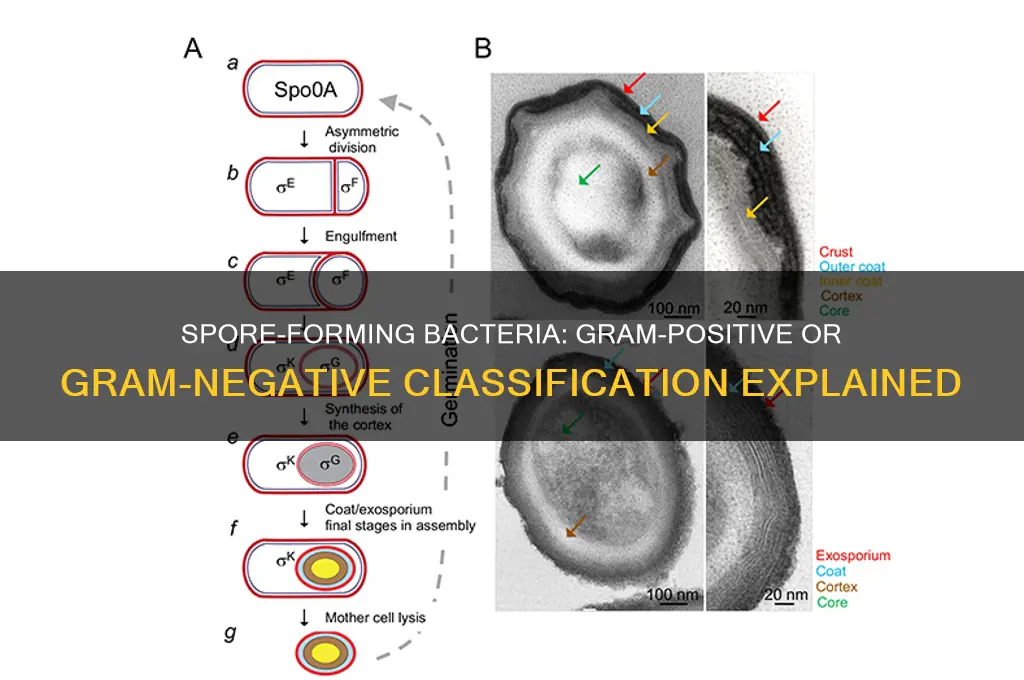

Sporulation begins when a bacterium detects environmental stressors such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, or extreme temperatures. In *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for studying sporulation, this signal is relayed through a phosphorelay system involving kinases and response regulators. The master regulator Spo0A is activated, initiating the genetic program for spore formation. This stage is critical, as it determines whether the cell commits to the energy-intensive process of sporulation or continues vegetative growth. For instance, in food preservation, understanding this trigger can help optimize conditions to inhibit spore formation in contaminants.

Morphological Changes: Building the Spore Structure

Once sporulation is initiated, the cell undergoes asymmetric division, forming a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. The forespore is engulfed by the mother cell in a process akin to phagocytosis, creating a double-membrane structure. The mother cell then synthesizes a thick, protective coat composed of proteins, peptidoglycan, and sometimes additional layers like the exosporium. This coat is responsible for the spore’s resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, making them a significant concern in canned food production.

Maturation and Resistance: The Final Stages

During maturation, the spore dehydrates, and its DNA is compacted and protected by proteins like SASP (small acid-soluble proteins). These proteins bind to DNA, stabilizing it against damage from heat, UV radiation, and enzymes. The mature spore is metabolically dormant, with its core in a glass-like state that further enhances resistance. This stage is why spores can persist in soil, dust, and processed foods for years. In industrial settings, treatments like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes are required to ensure spore inactivation, highlighting their remarkable resilience.

Germination: Reversing the Process

Spores remain dormant until they encounter favorable conditions, such as nutrients and appropriate temperature. Germination is triggered by specific nutrients like amino acids or sugars, which activate enzymes that degrade the spore coat and restore metabolic activity. This process is rapid, allowing the bacterium to resume vegetative growth within minutes. Understanding germination is vital for developing strategies to prevent spore outgrowth in food or clinical settings. For instance, combining heat treatment with spore germinants can enhance the efficacy of sterilization processes.

Practical Implications and Takeaways

The spore formation mechanism is a testament to bacterial adaptability, but it also presents challenges in food safety, healthcare, and biotechnology. By targeting specific stages of sporulation or germination, scientists can develop more effective antimicrobial strategies. For example, disrupting the Spo0A signaling pathway could prevent spore formation, while inhibiting germination enzymes could control spore outgrowth. Whether you’re a food scientist optimizing preservation methods or a microbiologist studying bacterial survival, understanding this mechanism provides actionable insights for combating spore-forming bacteria.

Understanding Spores: Biology's Tiny Survival Masters Explained Simply

You may want to see also

Gram Staining Characteristics

Spore-forming bacteria present a unique challenge in microbiology due to their resilience and distinct cellular structures. Understanding their Gram staining characteristics is crucial for accurate identification and classification. Gram staining, a differential staining technique, categorizes bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-negative based on their cell wall composition. However, spore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, exhibit specific traits that influence their staining behavior.

Analytically, the Gram staining process involves four steps: crystal violet staining, iodine fixation, alcohol decolorization, and safranin counterstaining. Gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet stain due to their thick peptidoglycan layer, appearing purple under a microscope. Gram-negative bacteria, with a thinner peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane, lose the crystal violet stain during decolorization and appear pink after safranin counterstaining. Spore-forming bacteria, predominantly Gram-positive, retain the purple stain, but their spores may not stain uniformly due to their impermeable outer coat. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores often require specialized staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton method to enhance visibility.

Instructively, when performing Gram staining on spore-forming bacteria, it’s essential to heat-fix the smear to adhere cells to the slide and prevent wash-off during staining. After the initial crystal violet and iodine steps, decolorize carefully; over-decolorization can lead to false-negative results. For spores, extend the staining time or use a spore-specific stain to ensure accurate visualization. Always examine the slide under oil immersion (1000x magnification) to distinguish spores from vegetative cells, as spores appear as refractile, oval bodies adjacent to the bacterial cell.

Persuasively, mastering Gram staining for spore-forming bacteria is not just a technical skill but a diagnostic necessity. Misidentification can lead to inappropriate treatment, particularly in clinical settings where pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* require specific antimicrobial therapy. For example, *C. difficile* spores are a key factor in recurrent infections, and their accurate detection through staining and culture is critical for patient management. By understanding the unique staining characteristics of these bacteria, microbiologists can provide actionable insights that directly impact patient care.

Comparatively, while most spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, exceptions exist. *Desulfotomaculum*, a spore-forming genus, is Gram-negative, highlighting the importance of not relying solely on Gram staining for identification. Additionally, the Gram-variable nature of some bacteria, such as *Corynebacterium*, can complicate interpretation. However, spore-forming bacteria’s consistent Gram-positive staining, coupled with their distinctive spore morphology, makes them a reliable group for identification through this technique.

In conclusion, Gram staining remains a cornerstone of bacterial identification, but its application to spore-forming bacteria requires nuanced understanding. By recognizing their unique staining characteristics and employing appropriate techniques, microbiologists can accurately classify these resilient organisms, ensuring precise diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Examples of Spore-Forming Bacteria

Spore-forming bacteria are a unique group of microorganisms capable of producing highly resistant endospores, allowing them to survive extreme conditions. Among these, Clostridium botulinum stands out as a notorious example. This Gram-positive bacterium is the culprit behind botulism, a severe form of food poisoning. Found in improperly canned foods, it thrives in anaerobic environments and produces a potent neurotoxin. To mitigate risk, ensure canned goods are heated to 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes before consumption, as this destroys both spores and toxins.

In contrast, Bacillus anthracis, another Gram-positive spore-former, is the causative agent of anthrax. This bacterium primarily affects livestock but can also infect humans through contact with contaminated animal products or inhalation of spores. Its spores are remarkably resilient, surviving in soil for decades. Vaccination is available for high-risk groups, such as veterinarians and lab workers, and early treatment with antibiotics like ciprofloxacin (400 mg every 12 hours) is crucial for managing infections.

While most spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, Desulfotomaculum challenges this norm as a Gram-variable or Gram-negative exception. This bacterium thrives in anaerobic, sulfate-rich environments, such as deep sediments and oil reservoirs. Though not pathogenic, its ability to form spores highlights the diversity within this bacterial group. Studying such organisms provides insights into extremophile biology and potential biotechnological applications, such as bioremediation of contaminated sites.

For practical purposes, understanding spore-forming bacteria is essential in industries like food preservation and healthcare. Bacillus cereus, a common contaminant in rice and dairy products, causes foodborne illness when its spores survive cooking and germinate. To prevent this, refrigerate cooked rice within 2 hours and reheat it thoroughly to 74°C (165°F) before consumption. These examples underscore the importance of targeted strategies to manage spore-formers, whether Gram-positive or the rare exceptions.

Mastering Shroud Spore Collection in Enshrouded: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gram-Positive vs. Gram-Negative Spores

Spore-forming bacteria are a unique subset of microorganisms capable of producing highly resistant endospores, allowing them to survive extreme conditions. Among these, Gram-positive bacteria dominate the spore-forming category, with notable examples including *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species. These bacteria retain the crystal violet stain in the Gram-staining process due to their thick peptidoglycan cell wall. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria are generally not known for spore formation, though rare exceptions like *Xanthomonas* exist. This distinction is critical in clinical and industrial settings, as Gram-positive spores pose unique challenges in sterilization and infection control.

Understanding the structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria sheds light on why spore formation is predominantly a Gram-positive trait. Gram-positive bacteria have a simpler cell envelope with a single, thick peptidoglycan layer, which facilitates the development of endospores. Gram-negative bacteria, however, possess a more complex cell envelope with an outer membrane and a thin peptidoglycan layer, making spore formation energetically and structurally less feasible. This anatomical disparity explains why Gram-positive spores are more prevalent and resilient, often requiring autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure complete eradication.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between Gram-positive and Gram-negative spores is essential in healthcare and food safety. Gram-positive spores, such as those of *Clostridioides difficile*, are notorious for causing hospital-acquired infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients or those on prolonged antibiotic therapy. In contrast, Gram-negative spores are rarely encountered but can still pose risks in specific environments, such as agricultural settings where *Xanthomonas* species may contaminate crops. Effective disinfection protocols must account for these differences, with Gram-positive spores demanding more rigorous methods like steam sterilization or spore-specific disinfectants.

For industries reliant on sterilization, such as pharmaceuticals and food production, the Gram-positive nature of most spores dictates the choice of decontamination techniques. While Gram-negative bacteria are typically eliminated by less intense methods, Gram-positive spores necessitate more aggressive approaches. For instance, in canning processes, foods are heated to 116°C–121°C for several minutes to destroy *Bacillus* spores, which could otherwise survive standard pasteurization. This highlights the importance of tailoring sterilization strategies to the specific microbial threats present, with Gram-positive spores being a primary concern.

In summary, the distinction between Gram-positive and Gram-negative spores is not merely academic but has profound implications for public health and industry. Gram-positive bacteria’s dominance in spore formation, coupled with their structural resilience, makes them a focal point for sterilization efforts. While Gram-negative spores are rare, their existence underscores the need for comprehensive microbial risk assessments. By understanding these differences, professionals can implement targeted strategies to mitigate the risks posed by spore-forming bacteria, ensuring safety in clinical, industrial, and everyday contexts.

Mastering Spore Modding: A Step-by-Step Guide to Custom Creations

You may want to see also

Environmental Survival Advantages

Spore-forming bacteria, predominantly Gram-positive, possess a remarkable ability to survive harsh environmental conditions through sporulation. This process involves the formation of endospores, which are highly resistant structures capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemical disinfectants. Unlike Gram-negative bacteria, which lack this survival mechanism, Gram-positive spore-formers like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* can persist in soil, water, and even outer space for decades or centuries. This adaptability makes them both ecologically significant and clinically challenging, as their spores can contaminate food, medical equipment, and industrial processes.

Consider the practical implications of spore survival in healthcare settings. Endospores of *Clostridioides difficile*, for instance, can remain viable on hospital surfaces for up to 5 months, resisting standard alcohol-based disinfectants. To combat this, healthcare facilities must employ spore-specific cleaning agents like chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 5,000 ppm hypochlorite) or hydrogen peroxide vapor systems. For individuals handling spore-forming bacteria in laboratories, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes is essential to ensure complete spore inactivation. These measures highlight the critical need to understand and address the environmental resilience of Gram-positive spore-formers.

From an ecological perspective, the sporulation ability of Gram-positive bacteria plays a vital role in nutrient cycling and soil health. Spores act as a dormant reservoir, allowing bacteria to survive until conditions become favorable for growth. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can germinate rapidly in response to nutrients like amino acids or sugars, contributing to organic matter decomposition. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this trait by using spore-based biofertilizers to enhance soil microbial activity, particularly in nutrient-depleted or stressed environments. However, this same resilience poses risks in food preservation, as spores of *Bacillus cereus* or *Clostridium botulinum* can survive cooking temperatures and cause foodborne illnesses if not properly controlled.

A comparative analysis reveals why Gram-negative bacteria rarely form spores. Their outer membrane, while providing structural integrity, lacks the flexibility to accommodate the drastic cellular changes required for sporulation. Instead, Gram-negative bacteria rely on biofilm formation or cyst production for survival, which are less durable than endospores. This evolutionary divergence underscores the unique survival advantages of Gram-positive spore-formers, making them dominant in environments where long-term persistence is key. For researchers and industry professionals, this distinction is crucial when designing strategies to control or harness these organisms in biotechnology, agriculture, or public health.

In conclusion, the environmental survival advantages of Gram-positive spore-forming bacteria stem from their unparalleled ability to form endospores, a trait absent in Gram-negative counterparts. This mechanism enables them to thrive in extreme conditions, from hospital wards to nutrient-poor soils. By understanding these adaptations, we can develop targeted interventions—whether through enhanced disinfection protocols, biofertilizer applications, or food safety measures—to mitigate risks and capitalize on their ecological benefits. The key takeaway is clear: spore formation is not just a survival strategy but a defining feature that shapes the role of Gram-positive bacteria in diverse environments.

Are Botulism Spores Airborne? Unraveling the Truth and Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Most spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. However, there are a few exceptions, like *Desulfotomaculum*, which is a Gram-negative spore-former.

Gram-positive bacteria have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall, which provides structural support and may facilitate the spore formation process. This characteristic is more common in Gram-positive species compared to Gram-negative bacteria.

While rare, some Gram-negative bacteria, such as *Desulfotomaculum* and *Sporomusa*, can form spores. However, spore formation is much less common in Gram-negative species compared to Gram-positive bacteria.