The question of whether spores are considered alive is a fascinating intersection of biology and philosophy. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are highly resilient structures designed for survival in harsh conditions. They exist in a dormant state, often lacking metabolic activity, which raises debates about their classification as living entities. While they possess the potential to germinate and grow into new organisms under favorable conditions, their inactive state challenges traditional definitions of life, which typically require active metabolism and responsiveness. This ambiguity invites exploration into the boundaries of what we define as alive and highlights the remarkable adaptability of spores in the natural world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Metabolic Activity | Spores exhibit minimal to no metabolic activity, appearing dormant. |

| Reproduction | Spores are reproductive structures capable of developing into new organisms under favorable conditions. |

| Growth | Spores do not grow or increase in size while in their dormant state. |

| Response to Stimuli | Spores can respond to environmental cues (e.g., moisture, temperature) to germinate. |

| Cellular Structure | Spores have a protective outer layer and contain genetic material, but lack typical cellular functions. |

| Viability | Spores can remain viable for extended periods, even in harsh conditions. |

| Classification | Spores are considered alive due to their potential to resume metabolic activity and develop into living organisms. |

| Energy Utilization | Spores do not actively utilize energy until germination. |

| Scientific Consensus | Most scientists classify spores as alive due to their genetic material and potential for life. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores and Metabolism: Do spores exhibit metabolic activity, a key indicator of life

- Dormancy vs. Death: Is spore dormancy a form of life or suspended animation

- Reproduction Capability: Can spores reproduce, a fundamental characteristic of living organisms

- Response to Stimuli: Do spores respond to environmental changes, suggesting life processes

- Cellular Structure: Do spores maintain intact cellular structures necessary for life

Spores and Metabolism: Do spores exhibit metabolic activity, a key indicator of life?

Spores, often described as dormant survival structures, challenge our understanding of what it means to be alive. While they lack visible signs of activity, the question of whether they exhibit metabolic processes—a hallmark of life—remains a subject of scientific inquiry. To address this, we must first define metabolism: the chemical processes that sustain an organism, including energy production and maintenance of cellular structures. Spores, despite their quiescent state, are not entirely inactive. They possess the ability to repair DNA damage and maintain membrane integrity, albeit at a significantly reduced rate compared to their vegetative counterparts. This minimal activity raises the question: Is this enough to classify spores as metabolically active, and by extension, alive?

Consider the example of bacterial endospores, such as those formed by *Bacillus subtilis*. These spores can survive extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and desiccation, for centuries. During this time, they exhibit basal metabolic activity, including the synthesis of small molecules like ATP and the repair of cellular components. However, this activity is orders of magnitude lower than that of actively growing cells. For instance, the ATP production rate in spores is estimated to be less than 1% of that in vegetative cells. This minimal metabolism is sufficient for survival but insufficient for growth or reproduction, blurring the line between life and dormancy.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore metabolism has significant implications, particularly in fields like food preservation and medicine. For example, spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, a pathogen that causes botulism, can survive in low-oxygen environments and germinate under favorable conditions. To ensure food safety, manufacturers use processes like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) to kill spores, as their metabolic resilience makes them more resistant to heat than vegetative cells. Similarly, in medicine, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges in hospital settings, where their ability to persist in dormant states complicates infection control.

Comparatively, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, exhibit slightly different metabolic profiles. While they also enter a dormant state, they retain the capacity to sense environmental cues, such as changes in humidity or nutrient availability, which trigger germination. This sensory capability suggests a low-level metabolic activity, including signal transduction pathways, even in the dormant phase. Such observations highlight the diversity in spore behavior across species, making a universal definition of their metabolic status complex.

In conclusion, spores do exhibit metabolic activity, but at a level that challenges traditional definitions of life. Their ability to maintain cellular integrity, repair damage, and respond to environmental cues indicates that they are not entirely inactive. However, this activity is minimal and focused on survival rather than growth or reproduction. Whether this qualifies spores as "alive" depends on how one defines life—as a binary state or a spectrum of activity. For practical purposes, treating spores as metabolically active entities ensures effective strategies for their control and utilization, whether in preserving food, combating pathogens, or harnessing their resilience in biotechnology.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Spores Successfully

You may want to see also

Dormancy vs. Death: Is spore dormancy a form of life or suspended animation?

Spores, those microscopic survival pods of the microbial world, challenge our understanding of life’s boundaries. When a spore enters dormancy, it ceases metabolic activity, shedding nearly all signs of vitality. Yet, this state isn’t death—it’s a strategic retreat. Unlike dead cells, spores retain the capacity to revive under favorable conditions, a process called germination. This raises a critical question: Is dormancy a form of life, or merely suspended animation?

Consider the mechanics of spore dormancy. During sporulation, organisms like bacteria and fungi condense their DNA, shed water, and fortify their cell walls with resilient compounds like dipicolinic acid. Metabolism drops to near-zero, and growth halts. This state can persist for centuries, as evidenced by 250-million-year-old spores revived from salt crystals. Yet, the spore’s ability to detect environmental cues—such as temperature, pH, or nutrient availability—and respond by germinating suggests a latent awareness. It’s not alive in the conventional sense, but it’s far from dead.

To understand this paradox, compare spore dormancy to other forms of suspended animation. Hibernation in animals, for instance, involves reduced metabolism but retains measurable vital signs. Cryopreservation in humans pauses life by freezing cells, though revival remains speculative. Spores, however, are self-sufficient. They require no external energy source during dormancy and can endure extremes—radiation, desiccation, even the vacuum of space. This resilience blurs the line between life and non-life, positioning dormancy as a unique survival strategy rather than a passive state.

Practically, this distinction matters in fields like astrobiology and medicine. If spores aren’t "alive" during dormancy, they could theoretically bypass legal and ethical constraints on transporting biological material. Yet, their potential to revive demands caution. For instance, sterilizing spacecraft to prevent interplanetary contamination relies on distinguishing dormant spores from dead matter. Similarly, in medicine, understanding spore dormancy helps combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile*, which form spores to evade treatment.

Ultimately, spore dormancy defies binary categorization. It’s neither fully alive nor dead but exists in a liminal state—a testament to life’s adaptability. Viewing it as suspended animation underscores its passive endurance, while recognizing it as a form of life highlights its potential for renewal. The truth lies in this duality: dormancy is a survival mechanism that transcends traditional definitions, a reminder that life’s boundaries are far more fluid than we often assume.

Unveiling the Spore-Producing Structures: A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Reproduction Capability: Can spores reproduce, a fundamental characteristic of living organisms?

Spores, often dormant and resilient, challenge our understanding of life’s boundaries. To determine if they qualify as alive, we must examine their reproductive capability—a hallmark of living organisms. Unlike cells that divide through mitosis or meiosis, spores do not reproduce independently. Instead, they germinate under favorable conditions to produce new organisms, such as fungi or plants. This process, however, relies on external triggers like moisture, temperature, and nutrients, raising questions about their autonomy. If reproduction requires activation by the environment, can spores truly be considered self-replicating entities?

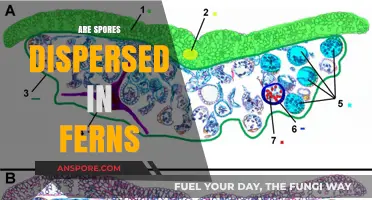

Consider the life cycle of a fern. Spores released from the parent plant are metabolically inactive, lacking the ability to reproduce until they land in suitable conditions. Once germinated, they grow into gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. Only through this indirect process does reproduction occur. This dependency on external factors contrasts with organisms like bacteria, which actively divide under their own metabolic control. Spores, in this sense, act more as survival mechanisms than independent reproducers, blurring the line between life and non-life.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore reproduction is crucial for fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, fungal spores in soil can remain dormant for years, only germinating when conditions are optimal. Farmers must manage these conditions—such as maintaining soil moisture below 50%—to prevent spore activation and subsequent crop damage. Similarly, in healthcare, controlling humidity levels (ideally below 60%) in hospitals reduces the risk of mold spore germination, which can cause infections in immunocompromised patients. These examples highlight how spore reproduction, though indirect, has tangible impacts.

A comparative analysis reveals that spores share traits with both living and non-living entities. Like seeds, they store genetic material and have the potential for growth, yet they lack metabolic activity until activated. This duality challenges traditional definitions of life, which often emphasize self-sustaining processes. If we define life by reproduction alone, spores fall short; if we include potential for growth and response to stimuli, they fit the criteria. This ambiguity suggests that categorizing spores as strictly alive or not may be too simplistic.

In conclusion, while spores cannot reproduce independently, their ability to germinate and initiate new life forms under specific conditions complicates their classification. They serve as a bridge between life and non-life, embodying resilience and adaptability. For practical purposes, treating spores as potential reproducers—and managing their environment accordingly—remains essential. Whether they are alive or not may ultimately depend on how broadly we define life, but their role in ecosystems and industries is undeniably vital.

Fungal Spores: Exploring Sexual and Asexual Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Response to Stimuli: Do spores respond to environmental changes, suggesting life processes?

Spores, often described as dormant survival structures, exhibit a fascinating ability to respond to environmental cues, blurring the line between life and non-life. When exposed to specific triggers such as moisture, temperature changes, or nutrient availability, spores can germinate and resume metabolic activity. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores, commonly found in soil, activate within minutes upon contact with water and specific nutrients, initiating a cascade of cellular processes. This responsiveness suggests that spores possess a latent capacity for life processes, even in their seemingly inert state.

To understand this phenomenon, consider the mechanism behind spore activation. Spores are encased in a protective coat that shields them from harsh conditions, yet they retain sensory systems capable of detecting environmental changes. For example, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus niger* respond to light and humidity gradients, orienting their growth toward optimal conditions. This targeted response is not random but a result of internal signaling pathways that interpret external stimuli, akin to basic life functions. Such specificity challenges the notion that spores are merely passive entities.

However, the debate arises when defining what constitutes a "life process." While spores respond to stimuli, their activity is minimal compared to actively growing cells. Critics argue that these responses are pre-programmed and lack the complexity of true metabolic regulation. Yet, even this programmed response requires functional biomolecules and energy reserves stored within the spore, indicating a level of biological preparedness. For practical purposes, understanding spore activation is crucial in fields like food preservation, where controlling environmental factors can prevent spoilage caused by spore germination.

A comparative analysis highlights the difference between spores and non-living entities. Unlike inert particles, spores exhibit threshold-dependent responses—for example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores require specific temperatures (above 10°C) and anaerobic conditions to germinate. This conditional reactivity contrasts with the static nature of non-living matter. Moreover, spores can repair DNA damage accumulated during dormancy, a process requiring enzymatic activity and energy, further supporting their classification as alive in a suspended state.

In conclusion, the ability of spores to respond to environmental changes provides compelling evidence for their status as living entities, albeit in a dormant form. Their sensory mechanisms, programmed responses, and metabolic potential align with fundamental life processes. While the debate persists, practical applications in microbiology and biotechnology underscore the significance of treating spores as biologically active agents. Recognizing their responsiveness not only advances scientific understanding but also informs strategies for managing spore-related challenges in health, agriculture, and industry.

Understanding Spore Plants: A Beginner's Guide to Their Unique Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Cellular Structure: Do spores maintain intact cellular structures necessary for life?

Spores, often described as nature’s survival capsules, raise a critical question: do they retain the cellular structures essential for life while dormant? Unlike active cells, spores enter a state of suspended animation, drastically reducing metabolic activity. Yet, their cellular integrity remains remarkably preserved. The cell wall, for instance, thickens and becomes impermeable, shielding internal components from environmental stressors. This structural adaptation is key to their longevity, allowing spores to endure extreme conditions—from scorching heat to freezing temperatures—for years, even centuries.

Consider the example of *Bacillus anthracis* spores, which maintain a dehydrated core with compacted DNA and minimal cytoplasmic activity. This preservation strategy ensures that vital cellular machinery, such as ribosomes and enzymes, remains intact but inactive. When conditions improve, the spore can rapidly rehydrate and resume metabolic functions, a process known as germination. This ability to maintain structural integrity while halting life processes blurs the line between life and non-life, challenging traditional definitions of vitality.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore cellular structure is crucial for industries like food preservation and medicine. For instance, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes is standard to destroy bacterial spores in medical equipment, targeting their resilient cell walls. Similarly, in agriculture, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum* require specific conditions to be eliminated, as their dormant structures resist conventional disinfectants. Knowing how spores preserve their cellular architecture helps develop effective strategies to combat them.

Comparatively, spores differ from vegetative cells in their ability to sacrifice immediate functionality for long-term survival. While vegetative cells prioritize active metabolism and reproduction, spores focus on structural preservation. This trade-off highlights a unique evolutionary strategy: spores are not "alive" in the conventional sense during dormancy, yet they retain the potential for life. Their cellular structures, though inactive, are meticulously maintained, serving as a blueprint for revival when conditions permit.

In conclusion, spores do maintain intact cellular structures necessary for life, albeit in a dormant, energy-conserving state. Their ability to preserve DNA, cell walls, and essential organelles while halting metabolic activity is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. This duality—being both alive and not—makes spores a fascinating subject for biological study and a critical consideration in practical applications, from sterilization protocols to environmental resilience. Understanding their cellular structure bridges the gap between theoretical biology and real-world problem-solving.

Understanding Moss Spores: Are They Diplohaplontic? A Detailed Look

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are considered alive as they are dormant reproductive structures produced by certain organisms, such as fungi, bacteria, and plants, capable of surviving harsh conditions and germinating under favorable conditions.

Spores have minimal metabolic activity while in their dormant state, but they retain the ability to revive and grow when conditions improve, making them biologically alive.

Yes, spores can be killed through extreme conditions such as high heat, radiation, or chemicals, as they are not invincible despite their resilience.

While both spores and seeds are reproductive structures, spores are typically unicellular and more resilient, whereas seeds are multicellular and contain a developing embryo. Both are considered alive due to their potential for growth.