Spores and pollen are both microscopic reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and certain other organisms, yet they serve distinct purposes and originate from different biological processes. Spores are typically associated with fungi, algae, and non-flowering plants like ferns, functioning as a means of asexual or sexual reproduction and dispersal, often capable of surviving harsh conditions. In contrast, pollen, produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and cone-bearing plants (gymnosperms), is a key component in sexual reproduction, facilitating the transfer of male gametes to female reproductive structures. While both spores and pollen play critical roles in the life cycles of their respective organisms, their structures, functions, and ecological significance differ significantly, reflecting the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world.

Explore related products

$16.95

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Process of spore creation in plants, fungi, and bacteria for survival and dispersal

- Pollen Structure: Anatomy of pollen grains, including exine, intine, and apertures for fertilization

- Spore vs. Pollen: Comparison of spores (reproductive units) and pollen (male gametophytes) in function

- Dispersal Mechanisms: How spores and pollen spread via wind, water, animals, or other agents

- Ecological Roles: Contributions of spores and pollen to ecosystems, biodiversity, and plant reproduction

Spore Formation: Process of spore creation in plants, fungi, and bacteria for survival and dispersal

Spores are nature’s ingenious solution to survival and dispersal, a microscopic marvel shared by plants, fungi, and bacteria. These lightweight, resilient structures are not just passive agents of propagation but are engineered to endure extreme conditions—heat, cold, drought, and even radiation. Their creation is a testament to evolutionary efficiency, ensuring species persistence across generations and habitats.

Consider the process in fungi, where spore formation, or sporulation, is a highly regulated response to nutrient depletion. Under stress, fungal cells undergo meiosis, producing haploid spores within specialized structures like sporangia or asci. For example, *Aspergillus* fungi release thousands of conidia, each capable of germinating into a new organism when conditions improve. This mechanism is not just about survival; it’s about opportunism, allowing fungi to colonize new environments rapidly.

In plants, spore formation is a cornerstone of the life cycle, particularly in ferns, mosses, and ferns. Sporophytes produce spores via meiosis, which develop into gametophytes—tiny, photosynthetic structures that generate reproductive cells. This alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity and adaptability. For instance, fern spores, dispersed by wind, can travel miles before landing in a suitable environment. Practical tip: gardeners can simulate this by scattering fern spores on moist soil in shaded areas to cultivate new plants.

Bacteria, though structurally simpler, employ spore formation as a last-ditch survival strategy. Endospores, formed by species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are metabolically dormant and encased in multiple protective layers. These spores can withstand boiling temperatures, UV radiation, and desiccation for decades. Hospitals and food industries must use autoclaves at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure complete sterilization, highlighting the tenacity of bacterial spores.

Comparatively, while plant and fungal spores are primarily reproductive, bacterial spores are purely survival mechanisms. This distinction underscores the versatility of spore formation across kingdoms. Whether for dispersal, genetic diversity, or endurance, spores are a unifying thread in the biological world, showcasing life’s adaptability in the face of adversity.

Shroomish's Spore Move: When and How to Unlock It

You may want to see also

Pollen Structure: Anatomy of pollen grains, including exine, intine, and apertures for fertilization

Pollen grains, the male reproductive units of seed plants, are marvels of natural engineering, optimized for protection, dispersal, and fertilization. At the heart of their structure lies a dual-layered wall: the exine and intine. The exine, composed of sporopollenin, is the outer, durable layer that withstands environmental stresses, from UV radiation to desiccation. Its intricate sculpturing—ranging from echinate (spiny) to reticulate (netted)—not only aids species identification but also enhances adhesion to pollinators. Beneath lies the intine, a thin, flexible layer of cellulose and pectin, providing elasticity during pollen tube growth. Together, these layers ensure pollen grains can travel vast distances while safeguarding the genetic material within.

A critical feature of pollen grains is their apertures, specialized openings that facilitate germination and fertilization. These structures, often likened to seams on a basketball, allow the pollen tube to emerge during germination. Monocots typically exhibit a single aperture (monosulcate), while eudicots have three (tricolpate). The position and number of apertures are taxonomically significant, aiding botanists in species classification. For instance, grasses have a single, elongated aperture (porus), which correlates with their wind-pollinated reproductive strategy. Understanding aperture morphology is not just academic—it informs agricultural practices, such as selecting pollen for hybridization in crop breeding programs.

To visualize pollen structure, consider a practical exercise: mount a pollen sample on a microscope slide with a drop of glycerin and examine it under 400x magnification. Observe the exine’s sculpturing patterns and locate the apertures. For beginners, sunflowers (*Helianthus annuus*) provide a clear example of tricolpate pollen, while lilies (*Lilium* spp.) showcase monosulcate grains. This hands-on approach reinforces theoretical knowledge and highlights the diversity of pollen morphology across plant families.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the exine’s resilience is a testament to its role in plant survival. Sporopollenin, one of nature’s most chemically inert compounds, ensures pollen grains can persist in fossil records for millions of years, offering paleobotanists insights into ancient ecosystems. Conversely, the intine’s fragility underscores its function in fertilization, as it must degrade to allow the pollen tube to penetrate the stigma. This duality—strength for dispersal, vulnerability for reproduction—exemplifies the balance between competing biological demands.

In applied contexts, understanding pollen structure has tangible benefits. For allergy sufferers, knowing that pollen grains with smoother exines (e.g., ragweed) are more allergenic can guide exposure avoidance strategies. In agriculture, optimizing pollination efficiency relies on matching pollen morphology with pollinator behavior—wind-pollinated plants produce smaller, lighter grains, while insect-pollinated species invest in larger, stickier ones. By dissecting the anatomy of pollen grains, we unlock not only botanical mysteries but also practical solutions for health, ecology, and industry.

Are All Spore-Forming Bacteria Gram-Positive? Unraveling the Myth

You may want to see also

Spore vs. Pollen: Comparison of spores (reproductive units) and pollen (male gametophytes) in function

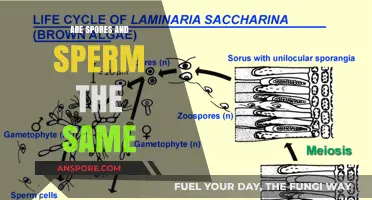

Spores and pollen, though both reproductive units, serve distinct functions in the plant kingdom. Spores are the asexual reproductive structures of plants like ferns and fungi, capable of developing into new organisms without fertilization. In contrast, pollen, produced by seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), is a male gametophyte that requires fertilization to initiate seed development. This fundamental difference in reproductive strategy highlights their roles: spores ensure survival and dispersal in harsh conditions, while pollen facilitates genetic diversity through sexual reproduction.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern versus a flowering plant to illustrate this contrast. Ferns release spores that germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) in moist environments. These prothalli produce eggs and sperm, which unite to form a new fern. This process is self-contained and does not require a partner. Conversely, a flowering plant produces pollen grains that travel via wind, water, or animals to reach the stigma of a compatible flower. Once there, the pollen tube grows to deliver sperm to the ovule, enabling fertilization and seed formation. This reliance on external factors underscores pollen’s role in promoting genetic recombination.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial for horticulture and conservation. For instance, gardeners propagating ferns can collect spores and sow them on a damp, sterile medium to grow new plants. In contrast, pollination management in crops like apples or almonds requires ensuring pollen transfer between compatible varieties, often through controlled bee activity. Misidentifying spores as pollen—or vice versa—could lead to ineffective propagation or failed harvests.

A persuasive argument for the importance of these distinctions lies in their ecological impact. Spores’ asexual nature allows rapid colonization of disturbed habitats, making them vital for ecosystem recovery after events like wildfires. Pollen, however, drives biodiversity by enabling cross-breeding, which is essential for species adaptation to changing climates. Without pollen’s genetic mixing, many plant populations would lack the resilience to survive environmental shifts.

In summary, while both spores and pollen are reproductive units, their functions diverge sharply. Spores prioritize survival and dispersal through asexual means, whereas pollen focuses on genetic diversity via sexual reproduction. Recognizing these differences not only aids in practical applications like gardening and agriculture but also underscores their ecological significance in maintaining plant life on Earth.

Are Fern Spores Harmful to Humans? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.61 $19.99

Dispersal Mechanisms: How spores and pollen spread via wind, water, animals, or other agents

Spores and pollen are nature's tiny travelers, equipped with ingenious strategies to disperse far and wide. Wind, the most common agent, whisks lightweight spores and pollen grains aloft, carrying them kilometers from their source. Fungi like puffballs exploit this method, releasing clouds of spores when disturbed, while grasses and pines produce vast quantities of pollen to increase the odds of fertilization. This passive yet effective mechanism relies on sheer volume and environmental currents, ensuring that even the smallest particles can colonize new territories.

Water, though less universal, plays a vital role in dispersal for aquatic and semi-aquatic plants. Mangroves, for instance, release buoyant propagules that float on tides, eventually lodging in suitable substrates to grow. Similarly, ferns often release spores near water bodies, allowing streams and rivers to transport them to damp, fertile grounds. This method is highly targeted, favoring environments conducive to germination, but its reach is limited compared to wind dispersal.

Animals, both intentionally and unintentionally, act as dispersal agents for spores and pollen. Bees, butterflies, and birds are classic pollinators, lured by nectar or color, transferring pollen between flowers as they feed. Less obvious are creatures like bats, which pollinate night-blooming plants, or ants, which disperse fungal spores by carrying them back to their nests. Even larger animals, like deer or rodents, can inadvertently transport spores on their fur or feet, acting as unwitting couriers.

Beyond these primary agents, other mechanisms exist, often blending creativity with necessity. Some plants, like the squirting cucumber, use explosive force to eject seeds and spores, while others rely on gravity, dropping spores directly to the ground. Human activity, too, has become an unintentional dispersal agent, spreading spores and pollen via agriculture, trade, and travel. Each method, whether natural or anthropogenic, highlights the adaptability of these microscopic entities in their quest for survival and propagation.

Botulism Spores in the Air: Uncovering the Hidden Presence

You may want to see also

Ecological Roles: Contributions of spores and pollen to ecosystems, biodiversity, and plant reproduction

Spores and pollen are microscopic powerhouses that drive ecosystem dynamics, biodiversity, and plant reproduction in ways both subtle and profound. These tiny structures, often overlooked, are the lifeblood of plant communities, ensuring species survival and ecological balance. Spores, produced by ferns, fungi, and non-flowering plants, are resilient pioneers, capable of withstanding harsh conditions until ideal environments trigger germination. Pollen, the male gametes of flowering plants, relies on wind, water, or animals for transport, facilitating genetic diversity through cross-pollination. Together, they form the foundation of plant life cycles, influencing everything from forest regeneration to food production.

Consider the role of spores in disturbed ecosystems. After a wildfire, for instance, soil-dwelling fern spores can rapidly colonize barren land, preventing erosion and preparing the ground for other plant species. This process, known as succession, showcases spores’ ability to act as ecological first responders. Similarly, fungal spores decompose organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the soil and supporting complex food webs. Without these contributions, ecosystems would struggle to recover from disturbances, and nutrient cycles would falter.

Pollen, on the other hand, is a cornerstone of biodiversity. Its dispersal mechanisms—wind, insects, birds, and bats—create genetic exchanges between distant plants, fostering adaptability and resilience. For example, a single bee can carry pollen from dozens of flowers in one foraging trip, enabling hybridization and strengthening plant populations against pests and diseases. This process is critical for crops like almonds, apples, and blueberries, which depend on pollinators for fruit production. In fact, approximately 75% of global food crops benefit from animal pollination, underscoring pollen’s economic and ecological value.

To harness the ecological benefits of spores and pollen, practical steps can be taken. Gardeners can plant spore-producing ferns and fungi to enhance soil health and promote biodiversity. Farmers can create pollinator habitats by planting wildflowers and reducing pesticide use, ensuring stable crop yields. Urban planners can incorporate green spaces with diverse plant species to support local ecosystems. Even individuals can contribute by avoiding excessive lawn mowing, as this allows flowering weeds to produce pollen for pollinators.

In conclusion, spores and pollen are not mere byproducts of plant reproduction but active agents of ecological stability and diversity. Their roles in nutrient cycling, succession, and genetic exchange highlight their indispensability to both natural and human-managed systems. By understanding and supporting these processes, we can foster healthier ecosystems and secure the future of plant life on Earth.

Are Spore Servers Still Active? Exploring the Current Status

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores and pollen are different. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants like ferns, fungi, and some algae, while pollen is produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms for reproduction.

Yes, both spores and pollen are involved in reproduction, but in different ways. Spores are used in the life cycles of non-flowering plants and fungi, while pollen is essential for the reproduction of flowering plants.

Spores and pollen can be harmful to some individuals. Certain fungal spores can cause allergies or infections, while pollen is a common trigger for seasonal allergies like hay fever.

Generally, individual spores and pollen grains are microscopic and not visible to the naked eye. However, large quantities of pollen or spores may appear as dust or powdery substances.

![Pollen [Jar] 22 Ounces](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61KWBB3OAML._AC_UL320_.jpg)