Spores are a critical reproductive structure in many organisms, particularly in plants, fungi, and some bacteria, but their cellular nature varies depending on the organism. In fungi, spores are typically unicellular, serving as a means of dispersal and survival in harsh conditions, while in plants like ferns and mosses, spores are also generally unicellular, functioning as the initial stage of their life cycle. However, in certain complex organisms, such as some algae, spores can be multicellular, though this is less common. Understanding whether spores are multicellular or unicellular is essential for grasping their role in reproduction, dispersal, and the evolutionary strategies of the organisms that produce them.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nature of Spores | Unicellular |

| Definition | Spores are single-celled, reproductive units produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, algae, and some protozoa. |

| Size | Typically small, ranging from 1 to 50 micrometers in diameter. |

| Cell Structure | Consist of a single cell with a protective outer wall or coat. |

| Function | Serve as a means of asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in adverse conditions. |

| Examples | Fungal spores (e.g., mold, mushrooms), plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses), bacterial endospores. |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods, sometimes years or even centuries. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. |

| Germination | Can germinate under favorable conditions to produce a new organism. |

| Mobility | Some spores (e.g., fungal spores) are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, while others remain stationary. |

| Reproductive Strategy | Primarily asexual, though some organisms (e.g., ferns) use spores in alternation of generations with sexual reproduction. |

Explore related products

$9.99 $10.99

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive structures, but are they single-celled or multi-celled organisms

- Fungal Spores: Most fungal spores are unicellular, produced by specialized structures like sporangia

- Plant Spores: Plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses) are typically unicellular and haploid

- Bacterial Spores: Bacterial spores (e.g., endospores) are unicellular, dormant survival structures

- Multicellular Exceptions: Some organisms produce multicellular spore-like structures, but true spores are unicellular

Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive structures, but are they single-celled or multi-celled organisms?

Spores are microscopic, lightweight, and highly resilient reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria. Their primary function is to ensure the survival and dispersal of the species, often in harsh environmental conditions. But the question remains: are spores single-celled or multi-celled organisms? To answer this, we must first understand their structure and purpose. Spores are typically haploid cells, meaning they contain half the number of chromosomes found in the parent organism. This characteristic is crucial for their role in sexual reproduction, where they fuse with another haploid cell to form a diploid zygote.

From an analytical perspective, the classification of spores as unicellular or multicellular depends on the organism producing them. For instance, fungal spores, such as those from mushrooms or molds, are unequivocally unicellular. Each spore is a single cell capable of developing into a new individual under favorable conditions. In contrast, some plant spores, like those from ferns or mosses, may contain multiple cells, albeit in a highly specialized and simplified form. However, even in these cases, the multicellular nature is transient and serves solely for dispersal and germination.

To illustrate, consider the life cycle of a fern. The fern produces spores in structures called sporangia. Each spore is a single cell that, when released, can germinate into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte is multicellular but exists solely to produce gametes for sexual reproduction. The resulting sporophyte (the mature fern) then produces new spores, completing the cycle. Here, the spore itself is unicellular, but it gives rise to a multicellular stage in the life cycle.

Persuasively, one could argue that the unicellular nature of spores is their defining feature. Their simplicity allows for extreme durability, enabling them to withstand desiccation, radiation, and other environmental stresses. For example, bacterial endospores, such as those produced by *Bacillus* species, are among the most resilient life forms on Earth. These unicellular structures can remain dormant for centuries, only to revive and grow when conditions improve. This adaptability underscores the evolutionary advantage of being unicellular.

In practical terms, understanding whether spores are unicellular or multicellular has implications for fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, knowing that fungal spores are unicellular helps in developing targeted fungicides that disrupt their cellular processes. Similarly, in plant breeding, recognizing the unicellular nature of spores aids in techniques like spore culture, where individual spores are grown into plants with desirable traits. For hobbyists or educators, this knowledge can enhance experiments, such as observing spore germination under a microscope or cultivating ferns from spores at home.

In conclusion, while spores are reproductive structures, their classification as unicellular or multicellular depends on the context. Fungal and bacterial spores are unequivocally unicellular, while plant spores may exhibit transient multicellularity during specific life stages. This distinction is not merely academic but has practical applications in science and everyday life. Whether you’re a researcher, gardener, or curious observer, understanding spores’ cellular nature deepens your appreciation for their role in the natural world.

Mold Spores Everywhere: Unseen, Ubiquitous, and Potentially Harmful?

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Most fungal spores are unicellular, produced by specialized structures like sporangia

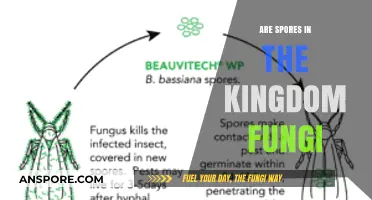

Fungal spores are predominantly unicellular, a fact that distinguishes them from the multicellular structures found in some other organisms. These microscopic units are the primary means by which fungi reproduce and disperse, ensuring their survival across diverse environments. Produced within specialized structures such as sporangia, asci, or basidia, fungal spores are marvels of efficiency, encapsulating genetic material and essential nutrients within a single cell. This unicellular nature allows them to remain dormant for extended periods, only germinating when conditions are favorable, such as in the presence of moisture and suitable temperature.

Consider the lifecycle of *Rhizopus stolonifer*, the common black bread mold. When you observe fuzzy black spots on stale bread, you’re seeing sporangia—sac-like structures filled with thousands of unicellular spores. Each spore, once released, can travel through the air and colonize new substrates, demonstrating the adaptability of this unicellular form. This process highlights the strategic advantage of unicellularity: minimal resource investment yields maximal dispersal potential. For gardeners or food handlers, understanding this mechanism underscores the importance of controlling humidity and airflow to prevent fungal growth.

From a comparative perspective, fungal spores contrast sharply with the multicellular spores of some plants, like ferns, which contain multiple cells and are structurally more complex. Fungal spores’ simplicity is their strength, enabling rapid production and dispersal. For instance, a single sporangium of *Physarum polycephalum* (a slime mold) can release up to 100,000 spores, each capable of independent survival. This efficiency makes fungi formidable colonizers, whether in decomposing organic matter or causing plant diseases. For farmers, recognizing this unicellular nature is crucial for implementing targeted fungicides, such as those containing chlorothalonil, applied at recommended dosages of 2–4 pounds per acre to disrupt spore germination.

Practically, the unicellular structure of fungal spores has implications for human health and industry. Inhalation of unicellular spores, such as those from *Aspergillus*, can lead to respiratory conditions like aspergillosis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Hospitals often monitor indoor air quality to limit spore counts below 500 CFU/m³, using HEPA filters and dehumidifiers to reduce fungal proliferation. Conversely, in biotechnology, unicellular fungal spores are harnessed for producing enzymes and antibiotics, such as penicillin from *Penicillium* spores, cultivated under controlled conditions to optimize yield.

In conclusion, the unicellular nature of most fungal spores is a testament to evolutionary efficiency, balancing simplicity with resilience. Whether viewed through the lens of ecology, agriculture, or medicine, understanding this characteristic empowers us to manage fungi effectively—whether as adversaries in food spoilage or allies in pharmaceutical production. By focusing on their unicellular design, we gain insights into both their vulnerabilities and their potential, guiding practical interventions across multiple fields.

Understanding Isolated Spore Syringes: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Cultivation

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses) are typically unicellular and haploid

Plant spores, particularly those of ferns and mosses, are predominantly unicellular and haploid, a characteristic that sets them apart in the plant kingdom. This unicellular nature means that each spore consists of a single cell, encapsulating all the genetic material necessary for growth. The haploid condition, with a single set of chromosomes, is a critical phase in the plant life cycle, enabling genetic diversity through sexual reproduction. For instance, when a fern spore germinates, it develops into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces both sperm and eggs, ensuring the continuation of the species.

Understanding the unicellular and haploid nature of plant spores is essential for horticulture and conservation efforts. Gardeners cultivating ferns or mosses must recognize that spores are not miniature plants but single cells requiring specific conditions to thrive. Spores need a moist, shaded environment to germinate successfully, and overwatering or direct sunlight can hinder their development. For example, when propagating moss, sprinkle spores evenly on a damp soil surface and cover with a thin layer of clear plastic to retain moisture, checking daily for signs of growth.

From an evolutionary perspective, the unicellular structure of plant spores highlights their efficiency as dispersal units. Their small size and lightweight allow them to travel vast distances via wind or water, colonizing new habitats with minimal energy expenditure. This adaptability is particularly evident in mosses, which can grow in harsh environments like rocky outcrops or tree bark, where multicellular structures would be less viable. The haploid state further enhances their survival, as it simplifies genetic recombination, fostering resilience in changing ecosystems.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend to education and research. Teachers can use fern or moss spores as hands-on tools to demonstrate the alternation of generations in plants, a fundamental concept in biology. Students can observe the transition from a unicellular spore to a multicellular gametophyte and sporophyte, reinforcing their understanding of plant life cycles. Researchers, meanwhile, study spore genetics to develop hardier plant varieties, leveraging their haploid nature to introduce beneficial traits more efficiently than in multicellular organisms.

In conclusion, the unicellular and haploid characteristics of plant spores like those of ferns and mosses are not merely biological curiosities but key adaptations that ensure their survival and propagation. Whether in gardening, conservation, education, or research, recognizing these traits allows for more effective interaction with and utilization of these remarkable organisms. By appreciating their simplicity and efficiency, we gain deeper insights into the intricate mechanisms of the natural world.

Best Places to Buy Shroom Spores Online and Locally

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bacterial Spores: Bacterial spores (e.g., endospores) are unicellular, dormant survival structures

Bacterial spores, particularly endospores, are remarkable unicellular structures that defy harsh environmental conditions. Produced by certain bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, these dormant forms are not just inactive cells but highly resistant survival pods. Unlike vegetative cells, endospores can withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and desiccation, making them a fascinating subject in microbiology. Their unicellular nature is key to their resilience, as it allows for minimal metabolic activity and maximum resource conservation.

To understand their unicellular classification, consider their formation process. During sporulation, a bacterium divides asymmetrically, creating a smaller cell (the forespore) within the larger mother cell. The forespore develops a protective coat, cortex, and spore membrane, eventually becoming a mature endospore. This entire structure remains a single cell, albeit one with specialized layers designed for survival. For instance, the cortex contains peptidoglycan, which absorbs heat and protects the DNA, while the outer coat repels chemicals and enzymes.

Practical applications of bacterial spores highlight their unicellular advantage. In medicine, spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used as biopesticides, targeting insect larvae without harming other organisms. In industry, spores are employed in bioremediation to degrade pollutants in extreme environments. However, their resilience also poses challenges, such as in food preservation, where spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling and cause botulism if not properly sterilized. To neutralize spores, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes is recommended, as this disrupts their protective layers.

Comparing bacterial spores to other spore types underscores their unicellular uniqueness. Fungal spores, for example, are often multicellular or part of a larger structure, like hyphae. In contrast, bacterial endospores are entirely self-contained, requiring no external support for survival. This distinction is crucial in fields like biotechnology, where understanding spore biology enables targeted interventions. For instance, researchers are exploring spore-based vaccines, leveraging their stability for long-term storage without refrigeration.

In conclusion, bacterial spores exemplify the ingenuity of unicellular life. Their dormant state, combined with unparalleled resistance, makes them both a challenge and a resource. Whether in scientific research, industrial applications, or everyday life, recognizing their unicellular nature provides insights into their behavior and potential. By studying these microscopic survivors, we unlock strategies for combating pathogens, preserving food, and advancing biotechnology.

Are Black Mold Spores Black? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Color

You may want to see also

Multicellular Exceptions: Some organisms produce multicellular spore-like structures, but true spores are unicellular

Spores, by definition, are unicellular structures designed for survival and dispersal. They are the resilient, dormant forms of various organisms, primarily fungi, plants, and some bacteria, capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. This unicellular nature is a fundamental characteristic that distinguishes true spores from other reproductive or survival structures. However, the biological world is full of exceptions, and some organisms blur the lines by producing multicellular structures that resemble spores in function but not in form.

Consider the case of certain algae, such as *Volvox*, which produces multicellular structures called "spores" during its life cycle. These structures are not true spores because they contain multiple cells, each with a specific role in germination and growth. Similarly, some fungi, like *Myxomycetes* (slime molds), form multicellular fruiting bodies that release unicellular spores. These examples highlight the complexity of classifying spore-like structures, as they often serve similar ecological functions despite their multicellular composition.

From an analytical perspective, the distinction between true spores and multicellular spore-like structures lies in their developmental origin and cellular organization. True spores arise from a single cell undergoing meiosis or mitosis, ensuring genetic diversity or clonal propagation. In contrast, multicellular spore-like structures develop from aggregates of cells that differentiate into specialized tissues. This difference is not merely semantic; it has implications for understanding evolutionary adaptations and survival strategies in diverse environments.

For practical purposes, distinguishing between true spores and multicellular exceptions is crucial in fields like agriculture, medicine, and environmental science. For instance, farmers and gardeners must recognize that fungal spores (unicellular) are the primary agents of plant diseases, while multicellular structures like fungal fruiting bodies are less directly harmful. Similarly, in microbiology, identifying unicellular bacterial spores (e.g., *Bacillus*) is essential for sterilization protocols, as these spores are notoriously resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation.

In conclusion, while true spores are unequivocally unicellular, the biological landscape includes multicellular structures that mimic their function. These exceptions underscore the diversity of life’s strategies for survival and dispersal. By understanding these distinctions, researchers and practitioners can better navigate the complexities of microbial and plant life cycles, ensuring more effective interventions in agriculture, medicine, and conservation.

Psilocybin Spores in Puerto Rico: Legal Status Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically unicellular structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria.

While most spores are unicellular, some organisms, like certain algae, produce multicellular spore structures, though these are less common.

Unicellular spores serve as reproductive units or survival structures, allowing organisms to withstand harsh conditions and disperse to new environments.

Yes, most fungi produce unicellular spores, such as conidia or basidiospores, as part of their life cycle for reproduction and dispersal.

Plant spores, including those from ferns, are generally unicellular, though they can develop into multicellular gametophytes under favorable conditions.

![AP Biology Prep Study Cards 2025-2026: AP Bio Review with Practice Test Questions for The Advanced Placement Biology Exam [2nd Edition]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51A-wgI5YaL._AC_UY218_.jpg)