The question of whether spores are N (nitrogen-fixing) or WN (non-nitrogen-fixing) hinges on the specific type of spore and the organism producing it. Spores, as reproductive or resistant structures, are found in various organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and plants. In the context of nitrogen fixation, certain bacterial spores, such as those from *Azotobacter*, are known to possess nitrogen-fixing capabilities (N), enabling them to convert atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form. However, most fungal and plant spores do not engage in nitrogen fixation and are thus considered WN. Understanding the nitrogen-fixing potential of spores is crucial for applications in agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology, as it influences soil fertility and nutrient cycling.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Classification: Are spores classified as N (non-motile) or WN (weakly motile) based on movement

- Spore Structure: How does spore structure influence its categorization as N or WN

- Environmental Factors: Do environmental conditions affect whether spores are N or WN

- Species Variation: Do different species produce spores that are N or WN

- Functional Implications: What are the ecological roles of N versus WN spores

Spore Classification: Are spores classified as N (non-motile) or WN (weakly motile) based on movement?

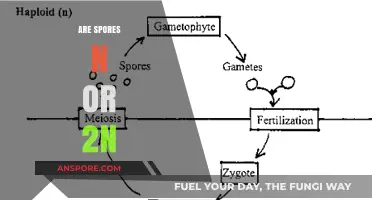

Spores, the resilient reproductive structures of certain organisms, exhibit a range of motility behaviors that challenge their straightforward classification as either N (non-motile) or WN (weakly motile). While many spores, such as those of plants and fungi, lack flagella and are undeniably non-motile (N), others, like bacterial endospores, do not fit neatly into this category. Bacterial endospores, for instance, are not inherently motile but can be passively dispersed by environmental factors like wind, water, or animal movement. This passive dispersal raises the question: does the absence of self-propelled movement automatically classify spores as N, or should external transport mechanisms be considered in their motility classification?

To address this, consider the distinction between active and passive movement. Active movement, driven by structures like flagella or cilia, is a clear indicator of motility. Spores lacking such structures are typically classified as N. However, weakly motile (WN) organisms exhibit limited self-propulsion, often relying on environmental currents or minimal energy expenditure. Since spores like bacterial endospores rely entirely on external forces for dispersal, they lack even the weak self-propulsion characteristic of WN organisms. This suggests that spores, in the absence of active movement mechanisms, should be firmly categorized as N, regardless of their dispersal efficiency.

A comparative analysis of spore types underscores this classification. Fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, are dispersed by air currents but remain non-motile (N) due to their lack of flagella or cilia. Similarly, plant spores, like those of ferns, rely on wind for dispersal yet are classified as N. In contrast, weakly motile organisms like *Giardia*, which possess flagella but move sluggishly, are categorized as WN. The key differentiator is the presence or absence of self-propulsion mechanisms, not the success of dispersal. Thus, spores, despite their diverse dispersal strategies, uniformly fall into the N category when evaluated by movement criteria.

Practical implications of this classification arise in fields like microbiology and ecology. For instance, understanding spore motility aids in predicting disease spread or environmental contamination. Non-motile spores (N) require external vectors for dispersal, making containment strategies more feasible. Conversely, weakly motile organisms (WN) pose greater challenges due to their limited self-propulsion. Researchers and practitioners can leverage this classification to design targeted interventions, such as air filtration systems for fungal spores or water treatment protocols for bacterial endospores. By focusing on movement mechanisms, rather than dispersal outcomes, spore classification becomes a precise tool for risk assessment and management.

In conclusion, spores are unequivocally classified as N (non-motile) based on their lack of self-propelled movement, regardless of their dispersal methods. This classification hinges on the absence of active movement structures and mechanisms, distinguishing spores from weakly motile organisms (WN). By adhering to this criterion, scientists and practitioners can accurately categorize spores, facilitating informed decisions in research, public health, and environmental management. The N classification, therefore, serves as a foundational principle in understanding spore behavior and its implications across disciplines.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Black Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: How does spore structure influence its categorization as N or WN?

Spore structure is a critical determinant in classifying spores as N (non-waterborne) or WN (waterborne). The outer layer, or exosporium, acts as the primary interface with the environment. In N spores, this layer is typically thicker and more hydrophobic, designed to resist moisture absorption and adhere to surfaces or air particles. Conversely, WN spores often feature a thinner, hydrophilic exosporium that facilitates dispersal in water, allowing them to remain suspended and viable in aquatic environments. This structural adaptation directly influences their transmission pathways and ecological niches.

Consider the spore size and shape, another key factor in categorization. N spores tend to be larger and more irregularly shaped, optimizing their ability to settle on surfaces or be carried by air currents. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores, classified as N, are 1–1.5 μm in diameter and have a rough exterior that enhances surface adhesion. In contrast, WN spores are often smaller and more spherical, reducing drag and enabling efficient dispersal in water. *Cryptosporidium* spores, a classic WN example, measure 4–6 μm and have a smooth surface that minimizes resistance in fluid environments.

The presence or absence of appendages also plays a role in spore classification. N spores frequently possess structures like filaments or spines that aid in attachment to surfaces or vectors, such as insect bodies or plant fibers. These appendages are less common in WN spores, which rely on buoyancy and water flow for dispersal. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* type E spores, categorized as WN, lack such appendages, allowing them to remain suspended in aquatic systems.

Practical implications of these structural differences are significant. For disinfection protocols, N spores require agents that penetrate thick exosporia, such as 70% ethanol or bleach solutions, while WN spores are more susceptible to filtration and chlorination. In environmental sampling, N spores are best collected using surface swabs or air filters, whereas WN spores are effectively captured through water filtration systems. Understanding these structural nuances ensures targeted and effective management strategies for both categories.

In summary, spore structure—exosporium composition, size, shape, and appendages—directly dictates whether a spore is classified as N or WN. These adaptations optimize survival and dispersal in specific environments, providing a scientific basis for categorization and practical applications in fields like public health and ecology. By analyzing these structural features, researchers and practitioners can better predict spore behavior and implement appropriate control measures.

Are Fern Spores Bearing Fruit for Your Garden? Find Out!

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Do environmental conditions affect whether spores are N or WN?

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, bacteria, and plants, exhibit a dichotomy in their behavior: they can either remain dormant (N) or become activated (WN) under specific conditions. Environmental factors play a pivotal role in tipping this balance, acting as catalysts or inhibitors of spore germination. Temperature, humidity, light exposure, and nutrient availability are among the key variables that dictate whether a spore remains in stasis or springs to life. For instance, fungal spores often require a narrow temperature range—typically between 20°C and 30°C—to transition from N to WN. Deviations from this range can prolong dormancy or render spores inviable.

Consider the practical implications for agriculture and food preservation. In grain storage facilities, maintaining a temperature below 15°C and relative humidity under 60% can keep fungal spores dormant, preventing spoilage. Conversely, in mushroom cultivation, controlled environments with temperatures around 25°C and high humidity (85–95%) are deliberately created to activate spores and promote growth. Light exposure also plays a subtle yet significant role; some spores, like those of certain ferns, require specific wavelengths of light to break dormancy, a phenomenon known as photodormancy.

The interplay of environmental factors can sometimes yield counterintuitive results. For example, while increased moisture generally favors spore activation, excessive waterlogging can deprive spores of oxygen, inhibiting germination. Similarly, nutrient availability is critical but must be balanced; a medium too rich in nutrients can attract competing microorganisms, hindering spore development. This delicate equilibrium underscores the need for precision in managing environments where spore behavior is critical, whether in biotechnology, horticulture, or pest control.

From a comparative perspective, bacterial spores (e.g., *Bacillus anthracis*) and fungal spores (e.g., *Aspergillus niger*) respond differently to environmental cues. Bacterial spores often require more extreme conditions, such as heat shock or specific chemical triggers, to transition from N to WN. Fungal spores, on the other hand, are more sensitive to gradual changes in humidity and temperature. Understanding these differences is essential for developing targeted strategies to either suppress or encourage spore activation in various contexts.

In conclusion, environmental conditions are not mere backdrop factors but active determinants of whether spores remain dormant or become active. By manipulating temperature, humidity, light, and nutrient availability, one can exert precise control over spore behavior. This knowledge is invaluable for industries ranging from agriculture to medicine, where managing spore activity is critical for success. Whether aiming to preserve food, cultivate crops, or combat pathogens, a nuanced understanding of these environmental factors empowers practitioners to harness the potential of spores effectively.

Exploring Fungi Reproduction: Sexual, Asexual, or Both?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species Variation: Do different species produce spores that are N or WN?

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of various organisms, exhibit a fascinating dichotomy in their nature: some are nucleated (N), while others are wall-nucleated (WN). This distinction is not arbitrary but reflects profound evolutionary adaptations. For instance, fungi like *Aspergillus* produce N spores, where genetic material remains centralized, optimizing rapid germination. In contrast, ferns generate WN spores, featuring a nucleus embedded within the cell wall, enhancing structural integrity during dispersal. This raises a critical question: does species variation dictate whether spores are N or WN?

To explore this, consider the ecological niches of spore-producing organisms. Aquatic species, such as certain algae, often produce WN spores to withstand harsh environmental conditions like desiccation or salinity. The thickened cell wall provides a protective barrier, ensuring survival in unpredictable habitats. Terrestrial species, like mushrooms, favor N spores, prioritizing quick colonization in nutrient-rich environments. This suggests that habitat pressures significantly influence spore type, with WN spores dominating in extreme conditions and N spores thriving in stable ecosystems.

However, phylogeny also plays a pivotal role. For example, all known bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) produce N spores, reflecting their ancestral lineage. Conversely, vascular plants like ferns and horsetails consistently produce WN spores, a trait linked to their evolutionary history. This phylogenetic constraint indicates that spore type is not merely an environmental response but a heritable characteristic shaped by evolutionary pathways. Cross-species comparisons reveal that while environmental factors can modulate spore resilience, genetic predisposition remains a dominant determinant.

Practical implications of this variation are noteworthy. In agriculture, understanding spore type can inform pest control strategies. For instance, targeting the N spores of fungal pathogens with nucleases could disrupt their germination, offering a precise biocontrol method. Similarly, in conservation, knowing whether a plant species produces WN spores can guide habitat restoration efforts, ensuring spores withstand transplantation stresses. For hobbyists cultivating ferns, recognizing their WN spores explains their slow germination, necessitating patience and controlled humidity during propagation.

In conclusion, species variation in spore type is a complex interplay of ecology and evolution. While environmental pressures favor WN spores in harsh conditions, phylogenetic constraints often dictate spore structure. This knowledge is not merely academic; it has tangible applications in fields from agriculture to conservation. Whether N or WN, spores are a testament to nature’s ingenuity, each type finely tuned to its species’ survival needs.

Are Psilocybe Spores Legal? Exploring the Legal Landscape and Implications

You may want to see also

Functional Implications: What are the ecological roles of N versus WN spores?

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of various organisms, exhibit distinct ecological roles based on their classification as N (non-windborne) or WN (windborne). N spores, typically larger and denser, rely on vectors like water, animals, or direct contact for dispersal. This localized strategy fosters niche adaptation, enabling species to thrive in specific microenvironments. For instance, fungal N spores in soil ecosystems contribute to nutrient cycling by decomposing organic matter, a process critical for plant growth. In contrast, WN spores, lightweight and aerodynamic, are designed for long-distance travel via air currents. This dispersal mechanism allows species to colonize new habitats rapidly, enhancing genetic diversity and survival in changing environments.

Consider the functional implications in agricultural settings. N spores of mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, improve nutrient uptake and soil structure. Farmers can enhance crop yields by inoculating seeds with these spores, particularly in nutrient-poor soils. However, overuse of such spores may disrupt natural soil microbial communities, necessitating careful dosage—typically 10–20 grams of spore inoculant per hectare. Conversely, WN spores of pathogens like *Puccinia graminis* (wheat rust) pose significant risks due to their ability to spread rapidly across fields. Implementing windbreaks and resistant crop varieties can mitigate their impact, demonstrating the need for tailored strategies based on spore type.

From a conservation perspective, understanding spore dispersal mechanisms is crucial for protecting biodiversity. N spores of bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) often depend on water for dispersal, making them indicators of wetland health. Conservation efforts should focus on preserving aquatic habitats to maintain these species. WN spores, such as those of ferns, contribute to forest regeneration by colonizing disturbed areas. Reforestation projects can leverage this trait by releasing WN spores in degraded zones, ensuring rapid vegetation recovery. However, invasive species with WN spores, like *Phragmites australis*, can outcompete native flora, requiring early detection and control measures.

The ecological roles of N and WN spores also intersect with climate change. N spores of thermophilic fungi, adapted to high temperatures, may become dominant in warming soils, altering decomposition rates and carbon cycling. Monitoring these shifts is essential for predicting ecosystem responses to climate change. WN spores of Arctic lichens, dispersed over vast distances, could facilitate species migration to cooler regions, highlighting their role in adaptation. Researchers can track spore dispersal patterns using aerobiological samplers, collecting data at altitudes of 1–10 meters to assess windborne trends.

In practical terms, distinguishing between N and WN spores informs pest management and restoration efforts. For instance, N spores of biocontrol agents like *Trichoderma* can be applied directly to plant roots to combat soil-borne pathogens, ensuring targeted delivery. WN spores of beneficial bacteria, such as those used in aerial inoculation of crops, require precise timing—releases should coincide with calm evenings to maximize settling on target areas. Whether in agriculture, conservation, or research, recognizing the functional implications of spore types enables more effective and sustainable interventions.

Can Fungi Reproduce Without Spores? Exploring Alternative Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are neither N (noun) nor WN (whole number). Spores are biological structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, and the term "spore" is a noun.

N refers to a noun, while WN refers to a whole number. These terms are not applicable to spores, as spores are biological entities, not grammatical or numerical concepts.

No, spores cannot be classified as N (noun) or WN (whole number) in any scientific context. They are biological reproductive units, not linguistic or mathematical categories.

The question is confusing because it mixes biological terminology (spores) with unrelated linguistic (N for noun) and mathematical (WN for whole number) concepts, making it unclear and irrelevant.

Spores should be referred to as biological structures or reproductive units in scientific or general discussions. They are not categorized as N (noun) or WN (whole number).