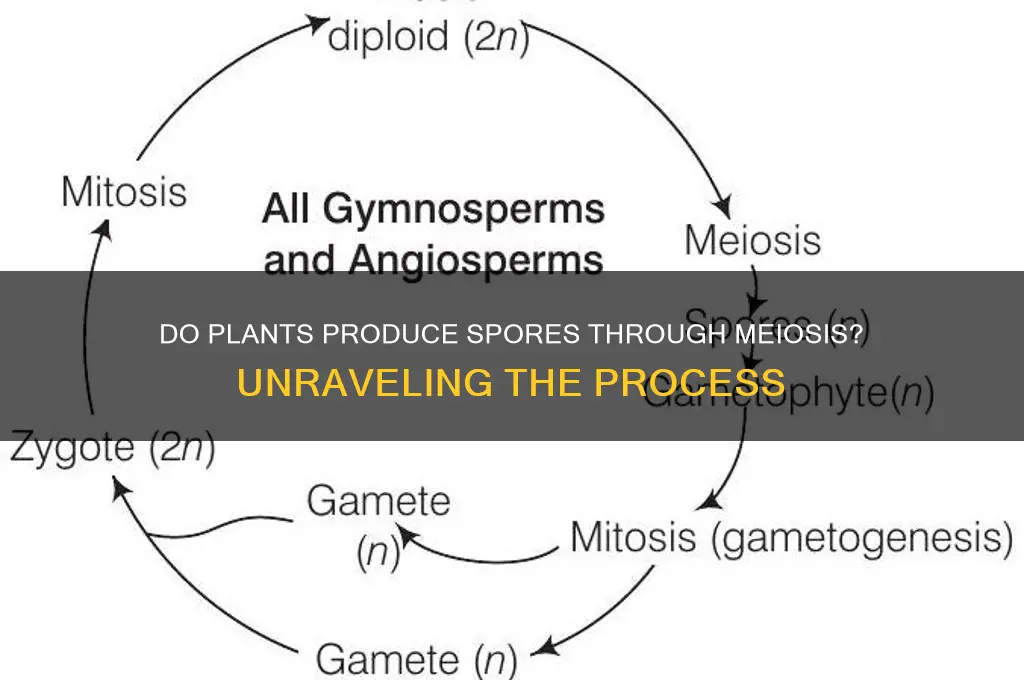

Spores in plants are typically produced through the process of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. This mechanism is crucial for the plant life cycle, particularly in alternating generations, where sporophytes (diploid plants) produce spores that develop into gametophytes (haploid plants). Meiosis ensures genetic diversity by shuffling genetic material through crossing over and independent assortment, which is essential for adaptation and survival in changing environments. While not all plant spores are produced via meiosis—some, like those in bacteria, arise through asexual methods—in vascular plants and many other plant groups, meiosis is the primary pathway for spore formation, playing a fundamental role in their reproductive strategies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Gametes: Differentiating spores formed by meiosis from gametes in plant reproductive cycles

- Meiosis in Sporophyte: Role of meiosis in sporophyte phase to produce haploid spores

- Types of Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., microspores, megaspores) produced via meiosis

- Spore Development: Process of spore formation post-meiosis in plant life cycles

- Alternation of Generations: How meiosis in sporophytes links to gametophyte generation in plants

Spores vs. Gametes: Differentiating spores formed by meiosis from gametes in plant reproductive cycles

Spores and gametes are both crucial to plant reproduction, yet they serve distinct roles and arise through different processes. Spores, typically produced via meiosis, are haploid cells that develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. In contrast, gametes—sperm and egg cells—are also haploid but are directly involved in fertilization, forming a diploid zygote. Understanding this distinction is key to grasping the complexity of plant reproductive cycles.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of spore-based reproduction. Here, the sporophyte (diploid) phase produces spores through meiosis, which germinate into gametophytes (haploid). These gametophytes then generate gametes, completing the cycle. In angiosperms (flowering plants), however, gametes are the primary reproductive units, produced within flowers. Spores, if present, are limited to specific structures like pollen grains, which are actually male gametophytes, not spores in the traditional sense.

Analyzing the function of spores versus gametes reveals their unique contributions. Spores act as survival structures, capable of withstanding harsh conditions until germination. Gametes, on the other hand, are specialized for immediate reproduction, requiring specific conditions to unite and form a new organism. For instance, in mosses, spores disperse widely, ensuring species survival, while gametes rely on water for fertilization, limiting their range.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in horticulture and agriculture. For seed-starting enthusiasts, understanding that spores require specific humidity and light conditions to thrive is essential. Gametes, in contrast, are managed indirectly through pollination techniques, such as hand-pollination in greenhouses. Misidentifying spores as gametes—or vice versa—can lead to failed propagation efforts, underscoring the importance of this distinction.

In conclusion, while both spores and gametes are haploid products of plant reproduction, their origins, functions, and applications differ markedly. Spores, formed by meiosis, are dispersal and survival units, whereas gametes are directly involved in fertilization. Recognizing these differences not only deepens our understanding of plant biology but also informs practical strategies in plant cultivation and conservation.

Mastering Spore Syringe Creation: A Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Sporophyte: Role of meiosis in sporophyte phase to produce haploid spores

In the life cycle of plants, the sporophyte phase is a critical stage where meiosis plays a pivotal role in producing haploid spores. Unlike the gametophyte phase, which is haploid, the sporophyte is diploid, carrying two sets of chromosomes. Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, occurs within the sporophyte’s sporangia, structures dedicated to spore production. This process reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid, ensuring genetic diversity through recombination. The resulting spores are not just miniature versions of the parent plant but genetically unique entities ready to develop into gametophytes under favorable conditions.

Consider the process step-by-step: meiosis begins with DNA replication in the sporophyte’s cells, followed by two rounds of division (Meiosis I and Meiosis II). During Meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material through crossing over, and then separate, reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiosis II further divides the sister chromatids, producing four haploid cells. These cells develop into spores, each carrying a single set of chromosomes. For example, in ferns, meiosis within the sporophyte’s sporangia produces spores that disperse and grow into gametophytes, which later produce gametes for sexual reproduction.

The role of meiosis in sporophyte-to-spore transition is not just about chromosome reduction; it’s a mechanism for survival and adaptation. Genetic recombination during meiosis introduces variability, allowing plant populations to respond to environmental changes. For instance, in crop plants like wheat or maize, meiosis ensures that spores (and subsequently seeds) inherit a mix of traits from both parents, enhancing resilience to pests, diseases, and climate fluctuations. This genetic diversity is why hybrid seeds often outperform inbred varieties in yield and vigor.

Practical applications of understanding meiosis in sporophytes extend to horticulture and agriculture. Breeders manipulate meiotic processes to develop new plant varieties, such as through hybridization or polyploidy induction. For home gardeners, knowing that spores are haploid products of meiosis explains why spore-grown plants (e.g., ferns or mosses) may exhibit variability. To cultivate spore-derived plants successfully, maintain humidity and provide a sterile medium, as spores are sensitive to desiccation and contamination.

In conclusion, meiosis in the sporophyte phase is the cornerstone of plant reproduction, bridging the diploid and haploid stages of the life cycle. It ensures genetic diversity through recombination and chromosome reduction, producing spores that are both genetically unique and essential for the next generation. Whether in natural ecosystems or agricultural settings, this process underscores the adaptability and resilience of plants, making it a fundamental concept for botanists, breeders, and enthusiasts alike.

Can You See Mold Spores? Unveiling the Invisible Threat in Your Home

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., microspores, megaspores) produced via meiosis

Spores are a fundamental part of plant reproduction, and their production is intricately tied to the process of meiosis. This cellular division reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells essential for sexual reproduction in plants. Among the diverse types of spores, microspores and megaspores stand out as key players in the life cycles of seed plants, particularly angiosperms and gymnosperms. Understanding their classification and function provides insight into the intricate mechanisms of plant reproduction.

Classification and Function: Microspores and Megaspores

Microspores and megaspores are the two primary types of spores produced via meiosis in seed plants. Microspores, smaller in size, develop into pollen grains, which are the male gametophytes. These spores are produced in the anthers of flowers in angiosperms or the microsporangia of cones in gymnosperms. Each microspore undergoes mitosis to form a pollen grain containing the male reproductive cells. In contrast, megaspores are larger and give rise to the female gametophytes, housed within the ovules. Typically, only one of the four megaspores produced by meiosis survives to develop into the female gametophyte, which contains the egg cell. This disparity in size and function reflects the distinct roles of male and female reproductive structures in plants.

The Meiosis Connection

Meiosis is the cornerstone of spore production, ensuring genetic diversity through recombination and reduction division. In the sporophyte generation of seed plants, spore mother cells undergo meiosis to produce tetrads of haploid spores. For microspores, this process occurs in the microsporangia, while megaspores are formed within the megasporangium (nucellus) of the ovule. The precision of meiosis is critical, as errors can lead to infertility or developmental abnormalities. For example, in angiosperms, the megaspore tetrad often follows a linear arrangement, with one functional megaspore developing into the female gametophyte, a process known as monosporic development.

Practical Implications and Examples

Understanding spore classification has practical applications in agriculture and horticulture. For instance, pollen viability tests in crop plants rely on assessing microspore development and meiosis efficiency. In hybrid seed production, controlling megaspore development is crucial for ensuring successful fertilization. Gymnosperms, such as pines, provide a contrasting example, where multiple megaspores may develop, but only one typically matures into a functional gametophyte. This diversity in spore development strategies highlights the adaptability of plant reproductive systems.

Takeaway: A Symphony of Reproduction

The classification of spores into microspores and megaspores underscores the elegance of plant reproductive biology. Produced via meiosis, these spores ensure genetic diversity and the continuity of species. Whether in the delicate flowers of angiosperms or the rugged cones of gymnosperms, the interplay of microspores and megaspores is a testament to the precision and efficiency of nature’s design. By studying these spores, we gain not only theoretical knowledge but also practical tools for improving plant breeding and conservation efforts.

Are Pterophyta Spores Safeguarded? Exploring Their Protective Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Development: Process of spore formation post-meiosis in plant life cycles

Spores in plants are not produced by meiosis itself but are a product of the developmental processes that follow meiosis. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells. In plants, these haploid cells then undergo a series of transformations to form spores, which are crucial for the alternation of generations in their life cycles. This post-meiotic phase is where the true complexity and ingenuity of spore development lie.

Consider the analytical perspective: After meiosis, the haploid spores are initially undifferentiated cells. In ferns, for example, these cells are housed within sporangia, structures located on the underside of fronds. The process of spore formation involves sporogenesis, where the meiotic products (microspores in seed plants or megaspores in ferns) undergo mitotic divisions to form mature spores. In angiosperms, microspores develop into pollen grains, while megaspores give rise to female gametophytes. This differentiation is tightly regulated by hormonal signals, such as auxin and gibberellins, which dictate cell fate and growth patterns.

From an instructive standpoint, understanding spore development is essential for plant propagation and conservation. For instance, in horticulture, spores of ferns are harvested and sown on sterile media to grow new plants. The key steps include: 1) Collection: Gather mature sporangia when they turn brown. 2) Sterilization: Treat spores with a dilute bleach solution to prevent contamination. 3) Sowing: Spread spores on a nutrient-rich agar medium. 4) Incubation: Maintain high humidity and indirect light for germination. This process mimics natural conditions, ensuring successful spore-to-plantlet development.

A comparative analysis highlights the diversity in spore development across plant groups. In bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), spores are released from capsules and germinate directly into gametophytes, bypassing complex sporophyte structures. In contrast, seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) produce spores that develop into gametophytes within protective structures (pollen grains and embryosacs). This divergence underscores the evolutionary adaptations that enhance spore survival and dispersal, such as the development of pollen walls or elaters in horsetails.

Finally, from a descriptive perspective, spore development is a marvel of biological precision. In mosses, the sporophyte grows from the gametophyte, producing a capsule where meiosis occurs. The capsule's hygroscopic elaters twist and turn in response to humidity, aiding spore dispersal. In angiosperms, the pollen grain's exine (outer wall) is sculpted with intricate patterns, enhancing its durability and interaction with stigma cells. These adaptations illustrate how post-meiotic processes are finely tuned to ensure the survival and propagation of plant species across diverse environments.

In summary, spore development post-meiosis is a multifaceted process that combines cellular differentiation, environmental adaptation, and evolutionary innovation. By studying this phase, we gain insights into plant life cycles and practical tools for horticulture and conservation. Whether through analytical dissection, instructional application, comparative study, or descriptive admiration, the journey from meiotic products to mature spores reveals the elegance and complexity of plant biology.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations: How meiosis in sporophytes links to gametophyte generation in plants

Spores in plants are indeed produced through meiosis, a process that occurs within the sporophyte generation. This fundamental mechanism underpins the alternation of generations, a life cycle characteristic of many plants, algae, and fungi. Meiosis in the sporophyte reduces the chromosome number, creating haploid spores that develop into the gametophyte generation. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as each generation serves distinct roles in the plant’s life cycle.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern as a practical example. The visible fern plant is the sporophyte, which produces spores via meiosis in structures called sporangia. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) that are often hidden beneath the soil or leaf litter. The gametophyte generation is short-lived but crucial, as it produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. Fertilization restores the diploid state, giving rise to a new sporophyte. This cyclical process highlights how meiosis in the sporophyte bridges the two generations, maintaining the balance between asexual spore production and sexual reproduction.

From an analytical perspective, the link between meiosis in sporophytes and the gametophyte generation is a strategic evolutionary adaptation. By alternating between diploid and haploid phases, plants maximize genetic recombination and reduce the risk of deleterious mutations. Meiosis in the sporophyte ensures that spores carry half the genetic material, allowing for independent growth and development of gametophytes. This separation of generations also enables plants to colonize diverse environments, as spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, while gametophytes focus on localized reproduction.

For those studying or teaching plant biology, understanding this process is essential. A practical tip is to use visual aids, such as diagrams or models, to illustrate the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte. For instance, demonstrate how a moss sporophyte grows on the gametophyte, relying on it for nutrients until spores are released. Caution against oversimplifying the relationship, as the dependency and interaction between generations vary across plant groups. For example, in angiosperms, the gametophyte is highly reduced, yet meiosis in the sporophyte remains critical for producing pollen and ovules.

In conclusion, meiosis in sporophytes is the linchpin of the alternation of generations, ensuring the continuity and diversity of plant life. By producing spores, the sporophyte generation sets the stage for the gametophyte’s role in sexual reproduction. This intricate cycle is a testament to the elegance of plant biology, offering insights into evolution, genetics, and ecology. Whether in a classroom or a garden, observing this process fosters a deeper appreciation for the complexity and resilience of the plant kingdom.

Discovering Timmask Spores: A Comprehensive Guide to Sourcing and Harvesting

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores in plants are typically produced through the process of meiosis, which results in haploid cells.

Meiosis in plants produces haploid spores, such as microspores (male) and megaspores (female), which develop into gametophytes.

Meiosis occurs during the sporophyte phase of the plant life cycle, leading to the formation of spores that give rise to the gametophyte generation.

No, only plants with an alternation of generations, such as ferns, mosses, and seed plants, produce spores through meiosis.

After meiosis, spores germinate and develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and egg) for sexual reproduction.