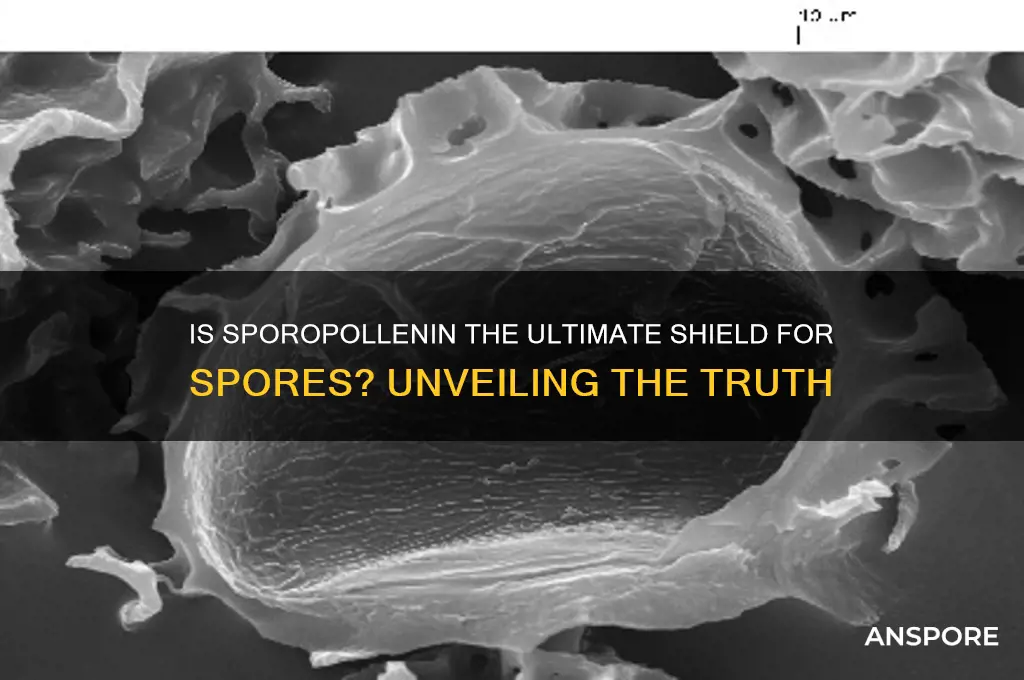

Spores, the reproductive units of many plants, algae, fungi, and some bacteria, are often encased in a resilient outer layer called sporopollenin. This complex biopolymer is renowned for its durability, providing spores with exceptional protection against environmental stresses such as UV radiation, desiccation, and chemical degradation. Sporopollenin’s unique chemical composition, which includes long-chain fatty acids and phenolic compounds, makes it highly resistant to breakdown, ensuring that spores can survive for extended periods in harsh conditions. This protective layer is crucial for the long-term viability of spores, enabling them to disperse widely and germinate under favorable conditions, thus playing a vital role in the survival and propagation of spore-producing organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protection | Spores are indeed protected by sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer. |

| Composition | Sporopollenin is composed of long-chain fatty acids, phenylpropanoids, and sporopollenin-specific proteins. |

| Structure | It forms a robust, multilayered outer wall around the spore, providing mechanical strength and chemical resistance. |

| Function | Protects spores from UV radiation, desiccation, extreme temperatures, and chemical degradation. |

| Durability | Sporopollenin is one of the most durable organic materials known, surviving for millions of years in the fossil record. |

| Permeability | It is impermeable to water and most chemicals, ensuring the spore's internal contents remain protected. |

| Taxonomic Distribution | Found in spores of plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and some fungi, but not in all spore-producing organisms. |

| Evolutionary Significance | Its presence has been crucial for the survival and dispersal of spore-producing organisms across diverse environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporopollenin's chemical structure and durability

Sporopollenin, the resilient biopolymer encapsulating spores and pollen grains, owes its extraordinary durability to a complex, cross-linked chemical structure. Composed primarily of long-chain fatty acids, phenylpropanoids, and sporopollenin-specific polymers, this biopolymer forms a highly stable matrix resistant to degradation. Unlike cellulose or chitin, sporopollenin lacks a uniform, repeating monomeric unit, instead relying on a heterogeneous arrangement of aromatic and aliphatic components. This structural heterogeneity, combined with extensive cross-linking, creates a material impervious to enzymes, acids, and even prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Such robustness ensures spores can survive extreme environmental conditions, from arid deserts to deep-sea sediments, for thousands—even millions—of years.

To understand sporopollenin’s durability, consider its synthesis process. During spore development, sporopollenin precursors undergo oxidative cross-linking, catalyzed by enzymes like peroxidases, to form a rigid exine layer. This cross-linking is not random; it follows a precise pattern dictated by the organism’s genetic code, resulting in a tailored structure optimized for protection. For instance, the exine of pollen grains often exhibits intricate sculpturing, such as ridges or spines, which enhance mechanical strength and reduce water penetration. This precision engineering at the molecular level is why sporopollenin remains intact in fossil records, providing paleobotanists with invaluable insights into ancient ecosystems.

Practical applications of sporopollenin’s durability are emerging in biotechnology and materials science. Researchers are exploring its use as a template for creating ultra-stable nanoparticles, leveraging its resistance to degradation for drug delivery systems. For example, sporopollenin-derived microcapsules have shown promise in encapsulating vaccines, protecting them from heat and light during storage and transport. To replicate this at a small scale, one could extract sporopollenin from pollen grains using a 1:1 ratio of hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid, followed by sonication to break down the exine layer. The resulting material can then be functionalized with polymers or drugs, offering a bioinspired solution for modern challenges.

Comparatively, sporopollenin’s durability surpasses that of synthetic polymers like polyethylene or polystyrene, which degrade over decades and contribute to environmental pollution. Its natural origin and biodegradability under specific conditions—such as exposure to certain fungi or extreme heat—make it an attractive candidate for sustainable materials. However, its complexity poses challenges for large-scale production. Synthetic biologists are addressing this by engineering microorganisms to produce sporopollenin-like polymers, aiming to mimic its structure without the need for plant extraction. Such innovations could revolutionize industries, from packaging to medicine, by combining nature’s resilience with human ingenuity.

In conclusion, sporopollenin’s chemical structure and durability are not just fascinating from a biological standpoint but also hold immense practical potential. Its heterogeneous composition, precise cross-linking, and resistance to degradation make it a model for designing next-generation materials. Whether in preserving ancient history or advancing modern technology, sporopollenin exemplifies how nature’s solutions can inspire and transform human innovation. By studying and replicating its properties, we unlock possibilities that bridge the gap between the microscopic world and macroscopic applications.

Mastering Mushroom Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Role in spore resistance to environmental stress

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, owe much of their durability to sporopollenin, a complex biopolymer that forms their outer wall. This substance is not merely a passive barrier but a dynamic shield that confers resistance to environmental stresses such as UV radiation, desiccation, and extreme temperatures. Its chemical composition, characterized by long-chain fatty acids and phenolic compounds, creates a robust, impermeable layer that safeguards the genetic material within. For instance, fungal spores coated in sporopollenin can survive in soil for decades, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This protective mechanism is a testament to nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species survival under harsh conditions.

To understand sporopollenin’s role in spore resistance, consider its structural properties. Unlike cellulose or chitin, sporopollenin lacks a regular, crystalline structure, making it highly resistant to degradation by enzymes or chemicals. This irregularity also contributes to its ability to scatter UV light, reducing DNA damage in spores exposed to sunlight. In practical terms, this means that spores from plants like ferns or fungi like *Aspergillus* can endure prolonged exposure to solar radiation without losing viability. For researchers or gardeners working with spore-based materials, this highlights the importance of considering sporopollenin’s protective effects when designing experiments or cultivation strategies.

A comparative analysis reveals that sporopollenin’s effectiveness varies across species, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to specific environments. For example, spores of extremophiles, such as those found in hot springs or polar regions, exhibit thicker sporopollenin layers compared to their temperate counterparts. This variation underscores the polymer’s adaptability in enhancing resistance to localized stressors. In agricultural applications, understanding these differences can inform the selection of spore-based bioinoculants for crops grown in challenging climates. For instance, using *Trichoderma* spores with robust sporopollenin coatings could improve soil health in arid regions by ensuring their survival during drought.

From a practical standpoint, leveraging sporopollenin’s protective properties requires strategic interventions. For laboratories culturing spores, maintaining low humidity (below 30%) during storage can prevent premature germination while preserving the sporopollenin’s integrity. Additionally, incorporating UV stabilizers in spore-based products, such as pollen supplements or fungal inoculants, can mimic sporopollenin’s natural UV-scattering ability. For hobbyists or educators demonstrating spore resilience, exposing samples to controlled stressors (e.g., 40°C heat for 24 hours) provides a tangible illustration of sporopollenin’s role in survival. These steps not only highlight the polymer’s significance but also offer actionable insights for optimizing spore-related practices.

In conclusion, sporopollenin’s role in spore resistance to environmental stress is a multifaceted phenomenon rooted in its unique chemistry and structure. Its ability to shield spores from UV damage, desiccation, and temperature extremes makes it a critical factor in the survival strategies of diverse organisms. By studying and applying this knowledge, scientists, farmers, and enthusiasts can harness sporopollenin’s potential to enhance spore-based technologies and practices. Whether in preserving biodiversity or improving crop yields, this biopolymer remains a cornerstone of resilience in the natural world.

Flowering Plants and Spores: Unraveling the Myth of Their Reproduction

You may want to see also

Sporopollenin's impact on spore longevity

Sporopollenin, a highly resilient biopolymer, forms the outer wall of spores and pollen grains, acting as a protective barrier against environmental stressors. Its chemical composition, primarily consisting of long-chain fatty acids and phenolic compounds, grants it exceptional durability. This unique structure enables sporopollenin to withstand extreme conditions, including desiccation, UV radiation, and enzymatic degradation, ensuring the longevity of spores across geological timescales. For instance, sporopollenin-encased spores have been recovered from sediments dating back millions of years, demonstrating its unparalleled protective capabilities.

To understand sporopollenin’s impact on spore longevity, consider its role in preventing water loss. Spores encased in sporopollenin exhibit significantly reduced permeability to water vapor, a critical factor in their survival during drought conditions. Studies have shown that sporopollenin’s hydrophobic nature allows spores to remain viable for decades, even in arid environments. For practical applications, such as seed banking or agricultural preservation, mimicking sporopollenin’s properties could enhance the shelf life of plant materials. A simple tip: storing seeds in low-humidity environments (<20% RH) can partially replicate the protective effect of sporopollenin, though synthetic sporopollenin coatings are under development for more robust solutions.

From a comparative perspective, sporopollenin’s protective efficacy surpasses that of other natural biopolymers, such as cellulose or chitin. While cellulose provides structural support in plant cell walls, it degrades rapidly under harsh conditions. Chitin, found in fungal cell walls and arthropod exoskeletons, offers moderate resistance to environmental stressors but lacks sporopollenin’s long-term stability. This superiority is evident in the fossil record, where sporopollenin-coated spores outlast other organic materials by orders of magnitude. For researchers, this highlights sporopollenin as a model for designing bioinspired materials with enhanced durability.

Persuasively, the study of sporopollenin’s impact on spore longevity has far-reaching implications for biotechnology and conservation. By unraveling its molecular structure and synthesis pathways, scientists could engineer sporopollenin-like materials for applications in drug delivery, food preservation, and environmental remediation. For example, encapsulating vaccines or nutrients in sporopollenin-inspired coatings could extend their stability without refrigeration, benefiting remote or resource-limited regions. A cautionary note: while sporopollenin’s resilience is advantageous, its recalcitrance to degradation poses challenges for waste management, necessitating sustainable production and disposal strategies.

Descriptively, sporopollenin’s role in spore longevity is akin to a suit of armor, shielding genetic material from the ravages of time and environment. Its intricate layered structure, akin to a laminated composite, distributes stress and resists cracking, ensuring spores remain intact even under mechanical pressure. This natural engineering marvel inspires biomimetic designs in materials science, where sporopollenin’s principles are applied to create ultra-durable coatings and composites. For hobbyists and educators, observing sporopollenin under a microscope reveals its intricate texture, a testament to nature’s ingenuity in preserving life across generations.

Psilocybin Spores in Puerto Rico: Legal Status Explained

You may want to see also

Comparison with other protective biomaterials

Sporopollenin, the resilient biopolymer shielding spores and pollen grains, stands out among protective biomaterials for its unique composition and durability. Unlike chitin, which primarily fortifies fungal cell walls and arthropod exoskeletons, sporopollenin is chemically inert, resistant to degradation by enzymes, acids, and bases. This makes it an unparalleled protector in harsh environments, such as soil or water, where spores can remain dormant for centuries. While chitin’s structure relies on polysaccharides, sporopollenin’s complex blend of long-chain fatty acids and phenolic compounds grants it superior resistance to mechanical stress and chemical assault. For practical applications, sporopollenin’s stability is being explored in drug delivery systems, where its impermeability ensures controlled release of encapsulated compounds.

In contrast to cuticle waxes, which protect plant surfaces from water loss and pathogens, sporopollenin serves a fundamentally different purpose. Cuticle waxes are dynamic, adapting to environmental conditions by altering their thickness or composition, whereas sporopollenin is static, designed for long-term preservation. Cuticle waxes are lipid-based and biodegradable, making them less durable than sporopollenin’s robust structure. However, their flexibility offers advantages in short-term protection, such as preventing desiccation in leaves. For researchers, understanding these differences is crucial when engineering biomimetic materials; sporopollenin’s rigidity is ideal for preserving genetic material, while cuticle waxes inspire self-healing coatings for agricultural or industrial use.

When compared to silk fibroin, a protein-based biomaterial renowned for its strength and biocompatibility, sporopollenin’s protective role diverges significantly. Silk fibroin’s elasticity and biodegradability make it ideal for tissue engineering and sutures, but it lacks sporopollenin’s resistance to extreme conditions. Sporopollenin’s impermeability to water and gases ensures spores survive desiccation and radiation, whereas silk fibroin’s porous structure facilitates cellular interaction. For instance, in medical applications, silk fibroin is used in dissolvable implants, while sporopollenin’s durability is being tested in long-term storage solutions for vaccines or enzymes. This distinction highlights the importance of matching biomaterial properties to specific protective needs.

Finally, sporopollenin’s comparison to keratin, the protein found in hair, nails, and feathers, reveals a trade-off between flexibility and longevity. Keratin’s fibrous structure provides toughness and elasticity, essential for withstanding repeated stress, but it degrades over time. Sporopollenin, on the other hand, is virtually indestructible, ensuring spores remain intact for millennia. This makes sporopollenin a candidate for archival storage of biological materials, such as DNA or microbial cultures, where long-term stability is critical. While keratin’s applications lie in regenerative medicine and cosmetics, sporopollenin’s extreme durability positions it as a model for developing materials that withstand time and environmental extremes.

Are Psychoactive Spores Legal for Sale? Exploring the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Formation and function of the spore wall

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of plants, algae, fungi, and some protozoa, owe their durability to the spore wall. This intricate structure is not merely a passive barrier but a dynamic shield engineered for survival. Central to its composition is sporopollenin, a biopolymer renowned for its chemical inertness and mechanical robustness. Unlike cellulose, which degrades under harsh conditions, sporopollenin resists enzymes, acids, and even prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation, making it an ideal protective material. Its formation is a tightly regulated process, involving the deposition of layers that vary in thickness and composition depending on the organism’s ecological niche.

The formation of the spore wall begins during sporogenesis, a stage where cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. In plants like ferns and mosses, the process starts with the accumulation of sporopollenin precursors in the tapetum or spore-nurturing cells. These precursors, derived from phenylpropanoid and fatty acid pathways, are polymerized and deposited in layers around the developing spore. The outermost layer, often the thickest, acts as the primary defense against desiccation, pathogens, and mechanical stress. In fungi, such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, the spore wall is similarly fortified with sporopollenin, though the architecture differs, reflecting their unique life cycles and habitats.

Functionally, the spore wall serves multiple roles beyond protection. Its impermeable nature allows spores to survive in extreme environments, from arid deserts to the deep ocean. For instance, fungal spores can remain dormant for decades, only germinating when conditions are favorable. In plants, the spore wall also plays a role in dispersal. Its smooth or sculptured surface reduces friction, aiding wind or water transport. Additionally, the wall’s chemical composition can deter herbivores and microorganisms, ensuring the spore’s longevity in hostile ecosystems.

Practical applications of sporopollenin’s properties are emerging in biotechnology and materials science. Researchers are exploring its use in drug delivery systems, where its stability and biocompatibility could encapsulate and protect sensitive compounds. In agriculture, understanding spore wall formation could lead to the development of hardier crops, capable of withstanding drought or disease. For hobbyists cultivating ferns or orchids, knowing that sporopollenin protects spores from desiccation underscores the importance of maintaining humidity during propagation.

In summary, the spore wall is a marvel of biological engineering, with sporopollenin as its cornerstone. Its formation is a precise, organism-specific process, and its function extends beyond survival to include dispersal and defense. Whether in nature or the lab, the spore wall’s unique properties offer insights and opportunities for innovation, highlighting the elegance of evolutionary adaptation.

Understanding Plant Spores: Tiny Survival Units and Their Role in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Sporopollenin is a highly resistant biopolymer that forms the outer wall of spores and pollen grains. It provides protection against environmental stresses such as UV radiation, desiccation, and chemical degradation, ensuring spore survival over long periods.

Yes, sporopollenin is a universal component of spore and pollen walls in plants, fungi, and some algae. It is the primary protective layer that shields the genetic material inside the spore.

Sporopollenin's chemical structure is highly stable and resistant to breakdown, allowing spores to remain viable for thousands of years in harsh conditions. This durability is key to their role in reproduction and dispersal.

While sporopollenin is extremely resilient, it can be degraded over time by certain microorganisms, enzymes, and extreme environmental conditions. However, its breakdown is slow, contributing to the longevity of spores.