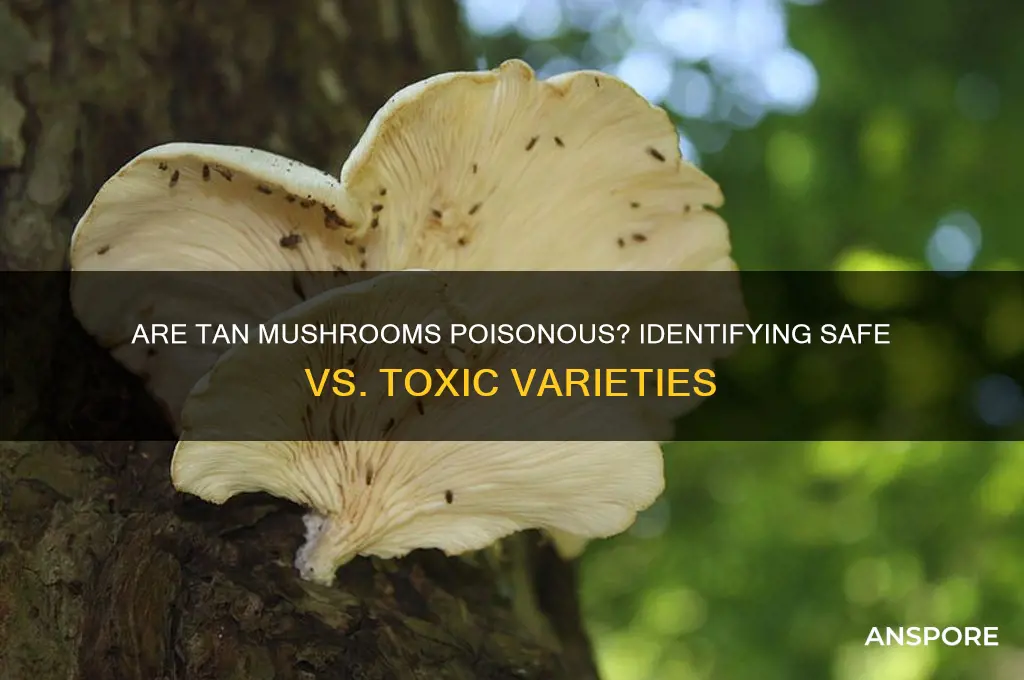

The question of whether tan mushrooms are poisonous is a critical one for foragers and nature enthusiasts alike, as mushroom identification can be notoriously tricky. Tan mushrooms encompass a wide variety of species, some of which are perfectly safe to eat, while others can be highly toxic or even deadly. Common edible tan mushrooms include the chanterelle and the oyster mushroom, prized for their culinary uses. However, poisonous varieties such as the deadly galerina or the poisonous amanitas can closely resemble their edible counterparts, making accurate identification essential. Factors like habitat, spore color, and physical characteristics must be carefully examined to avoid accidental poisoning. Misidentification can lead to severe symptoms, including gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, or even death, underscoring the importance of consulting expert guides or mycologists before consuming any wild mushrooms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identifying toxic tan mushrooms: key features to look for in poisonous species

- Common poisonous tan mushrooms: examples like the Death Cap and Destroying Angel

- Symptoms of poisoning: recognizing signs like nausea, vomiting, and organ failure

- Safe foraging tips: how to avoid toxic tan mushrooms while hunting

- Edible tan mushrooms: safe species like the Chanterelle and Lion’s Mane

Identifying toxic tan mushrooms: key features to look for in poisonous species

Tan mushrooms, while often innocuous, can harbor toxic species that pose serious health risks. Identifying these dangerous varieties requires a keen eye for specific features. One critical characteristic is the presence of a partial veil—a thin, membranous structure that often leaves a ring-like scar on the stem. Many toxic tan mushrooms, such as the deadly Amanita bisporigera, exhibit this feature. Always inspect the stem for such remnants, as their absence may indicate a safer species.

Another key feature to scrutinize is the gill attachment. Poisonous tan mushrooms often have gills that are free from the stem, meaning they do not extend down and attach to it. For instance, the Galerina marginata, a toxic look-alike of edible honey mushrooms, typically displays this trait. Compare the gill structure to known safe species, as this subtle difference can be a lifesaver.

The spore print is an underutilized but invaluable tool in mushroom identification. Toxic tan species often produce distinctive spore colors, such as rusty brown or dark brown. To create a spore print, place the cap gills-down on a piece of paper overnight. If the spores match those of known poisonous varieties, avoid consumption. This method is particularly useful for distinguishing between the toxic Cortinarius species and their edible counterparts.

Lastly, consider the habitat and seasonality of tan mushrooms. Many toxic species thrive in specific environments, such as coniferous forests or decaying wood. For example, the Clitocybe rivulosa, a poisonous tan mushroom, often appears in grassy areas during late summer and fall. Familiarize yourself with the typical habitats of toxic species in your region, as this knowledge can narrow down potential risks during foraging.

In summary, identifying toxic tan mushrooms hinges on observing specific features: partial veils, gill attachments, spore prints, and habitat clues. While no single trait guarantees toxicity, combining these observations significantly reduces the risk of misidentification. Always prioritize caution and consult expert resources when in doubt.

Are Enoki Mushrooms Safe for Cats? Risks and Facts Explained

You may want to see also

Common poisonous tan mushrooms: examples like the Death Cap and Destroying Angel

Tan mushrooms, while often innocuous, include some of the most deadly species known to foragers. Among these, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera* and *Amanita ocreata*) stand out as prime examples of lethal fungi. Both belong to the *Amanita* genus and share a tan or pale coloration, making them deceptively similar to edible varieties like the button mushroom. Their toxicity lies in amatoxins, which cause severe liver and kidney damage within 24–48 hours of ingestion. Even a small bite—as little as 50 grams of a Death Cap—can be fatal if left untreated.

To identify these dangers, focus on key features: the Death Cap has a greenish-tan cap, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. The Destroying Angel, as its name suggests, is pure white to tan, with a smooth cap and a similar volva. Both often grow near oak or birch trees, a habitat that overlaps with edible species, increasing the risk of misidentification. A critical rule for foragers: avoid any mushroom with a bulbous base and cup-like structure, as this is a hallmark of *Amanita* toxicity.

The symptoms of amatoxin poisoning are insidious. Initially, victims may experience nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can falsely suggest a simple stomach bug. However, after a symptom-free period of 24 hours, severe liver failure sets in, marked by jaundice, seizures, and coma. Treatment requires immediate medical attention, including activated charcoal, intravenous fluids, and, in severe cases, a liver transplant. Survival rates are higher when treatment begins within 6 hours of ingestion, underscoring the urgency of recognizing these mushrooms.

Comparatively, the Death Cap is more widespread, found across Europe, North America, and Australia, often introduced via imported trees. The Destroying Angel, while less common, is equally deadly and primarily found in North America. Both thrive in temperate climates and are most active in late summer to fall, coinciding with peak foraging season. This overlap increases the likelihood of accidental poisoning, particularly among inexperienced foragers who rely on color alone for identification.

To stay safe, adopt a multi-step approach: first, learn the specific traits of poisonous tan mushrooms, such as their volva and bulbous base. Second, carry a reliable field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app. Third, when in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk. Finally, educate children and pets about the dangers of wild mushrooms, as their curiosity can lead to accidental ingestion. By treating foraging with caution and respect, you can enjoy the hobby without falling victim to these silent killers.

Are Scotch Bonnet Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Symptoms of poisoning: recognizing signs like nausea, vomiting, and organ failure

Nausea and vomiting are often the body’s first alarm bells after ingesting a toxic tan mushroom. These symptoms typically appear within 6 to 24 hours, depending on the species and the amount consumed. For instance, the *Galerina marginata*, a tan mushroom often mistaken for edible varieties, contains amatoxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. If you or someone you know experiences persistent vomiting or nausea after mushroom consumption, seek medical attention immediately. Time is critical, as delayed treatment can lead to more severe complications.

Organ failure is a late-stage, life-threatening symptom of mushroom poisoning, particularly from species containing amatoxins or orellanine. Amatoxins, found in tan mushrooms like the *Lepiota* species, target the liver and kidneys, leading to acute failure within 3 to 9 days post-ingestion. Orellanine, present in the *Cortinarius* genus, primarily damages the kidneys, causing symptoms like dark urine, fatigue, and swelling. Children and the elderly are at higher risk due to their lower body mass and weaker immune systems. Monitoring for signs of jaundice, confusion, or decreased urine output is crucial, as these indicate organ distress.

Recognizing the progression of symptoms is key to survival. Early signs like nausea and vomiting may seem benign but can escalate rapidly. For example, a single *Galerina marginata* cap contains enough toxins to cause fatal liver failure in adults. If ingestion is suspected, activated charcoal may be administered within the first hour to reduce toxin absorption. However, this is no substitute for professional medical care. Blood tests, including liver and kidney function panels, are essential for diagnosis and treatment planning.

Prevention is the best defense. Avoid foraging for mushrooms without expert guidance, as tan varieties often mimic edible species. Teach children not to touch or eat wild mushrooms, and keep pets away from unknown fungi. If exposure occurs, document the mushroom’s appearance and save a sample for identification. Hospitals and poison control centers use this information to tailor treatment, which may include antidotes like silibinin for amatoxin poisoning or hemodialysis for kidney failure. Quick action and accurate information can mean the difference between recovery and tragedy.

Are Cup Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Safe Identification and Consumption

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe foraging tips: how to avoid toxic tan mushrooms while hunting

Foraging for mushrooms can be a rewarding activity, but it comes with risks, especially when tan mushrooms are involved. Not all tan mushrooms are toxic, but several dangerous species, like the deadly galerina (Galerina marginata), resemble common edible varieties. Misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. To avoid toxic tan mushrooms, start by educating yourself on the key characteristics of both edible and poisonous species. Field guides and local mycological clubs are invaluable resources for learning the subtle differences in cap texture, gill color, and spore print that distinguish safe from harmful varieties.

One practical tip is to focus on mushrooms with distinctive features that toxic tan species lack. For example, the edible lion’s mane mushroom (Hericium erinaceus) has cascading spines instead of gills, making it easy to differentiate from toxic look-alikes. Always carry a knife and a basket while foraging, not a plastic bag. A knife allows you to cut mushrooms at the base, preserving the ecosystem, while a basket lets spores disperse, aiding future growth. Avoid picking mushrooms near roadsides or industrial areas, as they may absorb pollutants, increasing health risks regardless of toxicity.

When in doubt, apply the "spore print test" to identify mushrooms more accurately. Place the cap gills-down on white and black paper overnight. The spore color—ranging from white to black, brown, or even pink—can help narrow down the species. For instance, the toxic galerina typically produces a rust-brown spore print, while many edible tan mushrooms, like the chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), produce a lighter yellow or white print. However, rely on this test as a supplementary tool, not a definitive identifier, as some toxic and edible species share spore colors.

Finally, adopt a cautious mindset: never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Even experienced foragers consult multiple sources or experts when unsure. Symptoms of mushroom poisoning can appear within 20 minutes to 24 hours, depending on the toxin. For example, amatoxins found in deadly galerina cause gastrointestinal distress followed by liver failure, while muscarine in certain toxic species induces sweating and salivation within minutes. If poisoning is suspected, contact a poison control center immediately and bring a sample of the mushroom for identification. Safe foraging is about patience, knowledge, and respect for nature’s complexities.

Are Mycena Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About These Glowing Fungi

You may want to see also

Edible tan mushrooms: safe species like the Chanterelle and Lion’s Mane

Not all tan mushrooms are created equal, and while some can be toxic, others are prized for their culinary and medicinal qualities. Among the safe and edible varieties, the Chanterelle and Lion’s Mane stand out as exceptional examples. These mushrooms not only boast a rich, earthy flavor but also offer nutritional and health benefits, making them a favorite among foragers and chefs alike. However, proper identification is crucial, as misidentification can lead to serious consequences.

The Chanterelle, with its golden-tan hue and forked gills, is a forager’s delight. Found in wooded areas across North America, Europe, and Asia, it thrives in symbiotic relationships with trees like oak and spruce. Its fruity aroma and chewy texture make it a versatile ingredient in soups, sauces, and sautéed dishes. To ensure safety, look for its characteristic wavy caps and absence of true gills—features that distinguish it from toxic look-alikes like the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom. Always cook Chanterelles thoroughly, as consuming them raw can cause mild digestive discomfort.

In contrast, the Lion’s Mane mushroom is a unique tan species known for its shaggy, icicle-like appearance. Often found on hardwood trees, it’s not just edible but also a powerhouse of bioactive compounds. Studies suggest that Lion’s Mane may support cognitive health, potentially aiding in nerve regeneration and reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. To prepare it, tear the mushroom into crab-like chunks and sauté or deep-fry for a crispy texture. Avoid overcooking, as it can become mushy. For medicinal use, consult a healthcare provider for dosage recommendations, typically ranging from 500 mg to 3 g daily in supplement form.

When foraging for these tan mushrooms, follow strict guidelines to avoid toxic species. Always carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. For beginners, joining a local mycological society or foraging with an expert can provide hands-on learning. Store harvested mushrooms in paper bags, not plastic, to prevent moisture buildup and spoilage.

In conclusion, while the question "are tan mushrooms poisonous?" often looms large, species like the Chanterelle and Lion’s Mane prove that not all tan fungi are dangerous. By understanding their unique characteristics and preparing them correctly, you can safely enjoy their flavors and benefits. Always prioritize caution and education in your foraging endeavors to turn a potentially perilous pursuit into a rewarding culinary adventure.

Are Shiitake Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all tan mushrooms are poisonous. Some tan mushrooms, like the Chanterelle, are edible and highly prized, while others, such as the Deadly Galerina, are toxic. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming.

Identifying poisonous tan mushrooms requires knowledge of specific features like gill color, spore print, and habitat. Consulting a field guide or expert is essential, as visual similarities can be misleading.

If you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately. Save a sample of the mushroom for identification and contact a poison control center or healthcare provider right away.