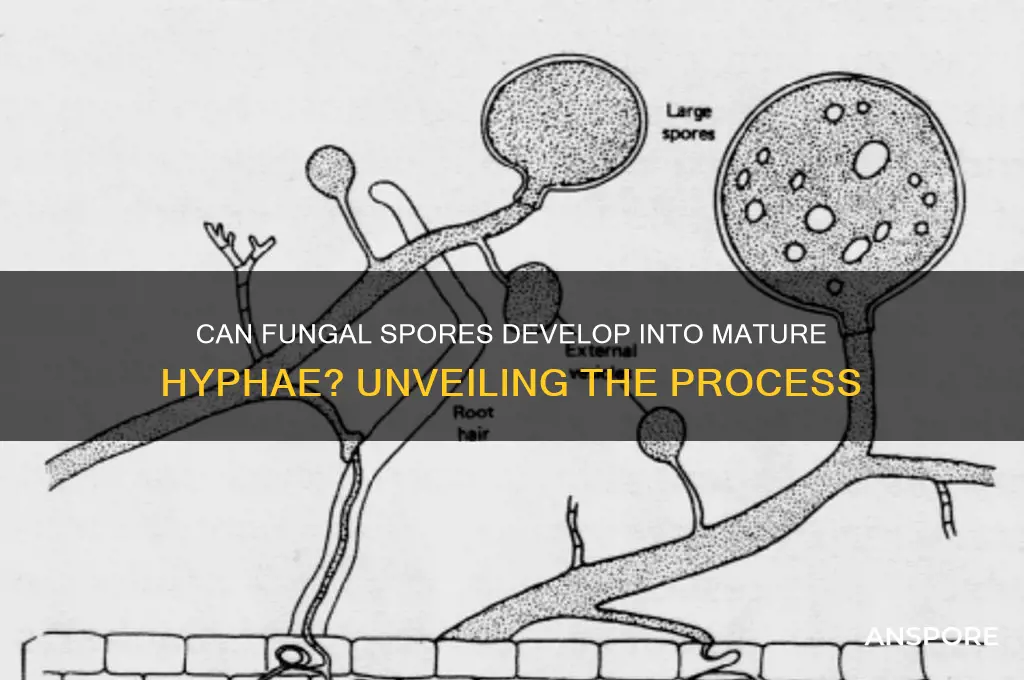

Fungal spores are microscopic, dormant structures produced by fungi as part of their reproductive cycle, serving as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. Once spores land in a suitable environment with adequate nutrients, moisture, and temperature, they can germinate and develop into mature fungal hyphae, the filamentous structures that form the body of the fungus. This transformation is a critical step in the fungal life cycle, enabling the organism to absorb nutrients, grow, and colonize new substrates. Understanding the conditions and mechanisms that allow spores to transition into hyphae is essential for fields such as mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as it sheds light on fungal ecology, pathogenicity, and potential control strategies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can fungal spores grow into mature fungal hyphae? | Yes |

| Process | Germination |

| Conditions Required | Moisture, suitable temperature, nutrients |

| Timeframe | Varies by species (hours to days) |

| Structure Formed | Hyphal network (mycelium) |

| Function of Hyphae | Absorption of nutrients, growth, reproduction |

| Types of Spores | Asexual (conidia, spores) and sexual (ascospores, basidiospores) |

| Germination Mechanism | Enzyme secretion to break dormancy, cell wall expansion |

| Environmental Factors | pH, oxygen availability, substrate type |

| Significance | Essential for fungal life cycle and ecosystem roles (decomposition, symbiosis) |

| Examples of Fungi | Aspergillus, Penicillium, Mucor, and many others |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Optimal environmental conditions for spore germination

Fungal spores, akin to seeds in the plant world, require specific environmental cues to transition from dormancy to active growth. This process, known as germination, is the critical first step in the development of mature fungal hyphae. Understanding the optimal conditions for spore germination is essential for both harnessing fungi in beneficial applications, such as agriculture and biotechnology, and controlling them in contexts like food preservation and medicine.

Temperature and Moisture: The Foundation of Germination

Fungal spores are highly sensitive to temperature and moisture, which act as primary triggers for germination. Most fungi thrive in temperatures ranging from 20°C to 30°C (68°F to 86°F), though some species, like those in thermophilic groups, require higher temperatures up to 50°C (122°F). Moisture is equally critical; spores typically require a water activity (aw) of at least 0.85 to initiate germination. However, excessive moisture can lead to waterlogging, depriving spores of oxygen and inhibiting growth. Practical tip: For laboratory or agricultural settings, maintain a relative humidity of 80–90% and monitor temperature closely to ensure optimal conditions.

Nutrient Availability: Fueling the Transition

While spores can remain dormant for extended periods without nutrients, germination and subsequent hyphal growth demand a carbon source, such as glucose or cellulose, and nitrogen, often in the form of ammonium or nitrate. The concentration of these nutrients is crucial; for example, a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 10:1 is ideal for many fungal species. Caution: Overabundance of nutrients, particularly sugars, can lead to osmotic stress, hindering germination. In practical applications, such as mushroom cultivation, use a substrate like straw or sawdust enriched with a balanced nutrient solution to support spore germination.

Light and pH: Subtle Yet Significant Factors

Light exposure and pH levels play nuanced roles in spore germination. Some fungi, like *Neurospora crassa*, require light to trigger germination, while others are inhibited by it. Similarly, pH influences spore viability, with most fungi preferring a slightly acidic to neutral environment (pH 5.0–7.0). Deviations from this range can denature enzymes essential for germination. For instance, *Aspergillus* species germinate optimally at pH 6.0–6.5. When preparing growth media, adjust pH using buffers like phosphate or acetate to ensure compatibility with the target fungal species.

Oxygen and Gas Exchange: Breathing Life into Spores

Aeration is vital for spore germination, as fungi are predominantly aerobic organisms. Oxygen is required for energy metabolism during the early stages of growth. In closed environments, such as petri dishes or fermentation tanks, ensure adequate gas exchange by using porous materials or periodically opening containers. However, some fungi, like certain yeasts, can tolerate anaerobic conditions, though this is less common. Practical tip: For large-scale cultivation, use aerated substrates or bioreactors with controlled oxygen levels to maximize germination rates.

By meticulously controlling temperature, moisture, nutrients, light, pH, and oxygen, one can create an environment that not only encourages spore germination but also fosters the development of robust fungal hyphae. This precision is key to unlocking the potential of fungi in diverse fields, from food production to environmental remediation.

Bacterial Spores: Their Role in Reproduction and Survival Explained

You may want to see also

Nutrient requirements for hyphal growth

Fungal spores, when provided with the right conditions, can indeed germinate and develop into mature fungal hyphae, the filamentous structures that form the body of a fungus. This transformation is not spontaneous; it requires a precise balance of nutrients to fuel the metabolic processes driving hyphal growth. Understanding these nutrient requirements is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications, such as agriculture, biotechnology, and medicine.

Essential Macronutrients for Hyphal Growth

Hyphal growth relies heavily on macronutrients, which are consumed in larger quantities. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus are the cornerstone elements. Carbon serves as the primary energy source and structural component, with glucose being a preferred carbon source for many fungi. However, fungi exhibit metabolic flexibility, utilizing alternative carbon sources like cellulose or lignin in nature. Nitrogen is critical for amino acid synthesis and nucleic acid production, with ammonium and nitrate being readily absorbed forms. Phosphorus, often taken up as phosphate, is essential for ATP synthesis and cell membrane integrity. Optimal growth typically occurs at a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 10:1, though this varies by species. For instance, *Aspergillus niger* thrives with 1% glucose and 0.1% ammonium nitrate in culture media.

Micronutrients and Their Role in Hyphal Development

While required in trace amounts, micronutrients are indispensable for hyphal growth. Magnesium, iron, and zinc are key players. Magnesium is a cofactor for enzymes involved in energy metabolism, while iron is vital for electron transport in respiration. Zinc supports DNA synthesis and protein function. Deficiencies in these elements can stunt growth or lead to abnormal hyphal morphology. For example, iron limitation often results in reduced branching and slower extension rates. Supplementing media with 0.01% iron sulfate can restore normal growth in iron-limited conditions. Additionally, vitamins like thiamine and biotin act as growth factors, particularly for auxotrophic fungi that cannot synthesize these compounds internally.

Water and pH: The Unseen Regulators

Water availability and pH are indirect but critical factors influencing nutrient uptake and hyphal growth. Fungi require free water for nutrient solubilization and transport, with most species growing optimally at water activity levels above 0.85. pH affects nutrient solubility and enzyme activity; most fungi prefer a slightly acidic to neutral pH range (4.5–7.0). Deviations can inhibit growth or alter hyphal architecture. For instance, *Trichoderma* species grow best at pH 5.0–6.0, while *Candida albicans* tolerates a broader range of 4.0–8.0. Buffering culture media with 0.1 M phosphate or acetate can stabilize pH and enhance growth consistency.

Practical Tips for Optimizing Hyphal Growth

For researchers and practitioners, achieving robust hyphal growth requires attention to detail. Start by using a defined medium like Sabouraud dextrose agar, which provides a balanced nutrient profile. Adjust carbon and nitrogen sources based on the fungal species; for example, replace glucose with sucrose for osmotolerant fungi. Monitor micronutrient concentrations, especially in long-term cultures, as depletion can occur. Sterilize media properly to prevent contamination, which competes for nutrients. Finally, maintain environmental conditions—temperature (25–30°C for most fungi) and humidity—to support optimal nutrient utilization. Regularly subculturing hyphae onto fresh media ensures continuous access to essential nutrients.

By meticulously managing these nutrient requirements, one can effectively cultivate mature fungal hyphae from spores, unlocking their potential in various fields from bioremediation to pharmaceutical production.

Exploring Soil: Are Spore-Forming Bacteria Common in Earth's Layers?

You may want to see also

Role of moisture in spore-to-hypha transition

Fungal spores, those microscopic survival units, remain dormant until conditions trigger their transformation into mature hyphae, the filamentous structures that define fungal growth. Among these conditions, moisture stands as a critical catalyst. Without adequate water, spores remain inert, unable to initiate metabolic processes or expand their cell walls. Even a slight increase in humidity can activate enzymes within the spore, breaking dormancy and signaling the start of germination. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores require water activity levels above 0.75 to transition into hyphae, while *Penicillium* can germinate at levels as low as 0.80. This threshold varies by species, highlighting moisture’s role as a species-specific trigger.

Consider the practical implications of moisture control in environments prone to fungal growth. In homes, maintaining relative humidity below 60% inhibits spore germination, a key strategy in mold prevention. Dehumidifiers, proper ventilation, and prompt repair of leaks are actionable steps to disrupt this transition. Conversely, in agricultural settings, controlled moisture levels are used to encourage beneficial fungal growth, such as mycorrhizal fungi that enhance plant nutrient uptake. Here, moisture isn’t just a preventive measure but a tool for fostering symbiotic relationships. The duality of moisture’s role—both inhibitor and enabler—underscores its importance in managing fungal ecosystems.

The mechanism by which moisture facilitates spore-to-hypha transition involves more than just hydration. Water acts as a solvent, enabling nutrient uptake and enzyme activity essential for cell wall expansion. During germination, spores absorb water, swelling and rupturing their protective outer layer. This process, known as imbibition, is followed by the emergence of a germ tube, the precursor to hyphal growth. Without sufficient moisture, this sequence stalls, leaving spores in a state of suspended animation. For example, *Fusarium* spores require a minimum of 0.90 water activity to initiate imbibition, a threshold that ensures their survival in dry soils until conditions improve.

A comparative analysis reveals that moisture’s role extends beyond mere presence to include timing and duration. Spores of *Trichoderma*, a biocontrol fungus, germinate rapidly in high-moisture environments but require prolonged exposure to develop extensive hyphal networks. In contrast, *Alternaria* spores can germinate in short moisture bursts, making them particularly resilient in fluctuating conditions. This adaptability explains their prevalence in damp, variable climates. Understanding these nuances allows for targeted interventions, such as intermittent drying cycles to disrupt *Alternaria* growth or sustained moisture to promote *Trichoderma* colonization.

In conclusion, moisture is not just a passive requirement but an active regulator of the spore-to-hypha transition. Its role is multifaceted, influencing germination thresholds, metabolic activation, and structural development. By manipulating moisture levels, whether through environmental control or strategic application, one can either suppress unwanted fungal growth or cultivate beneficial fungi. This knowledge transforms moisture from a simple environmental factor into a powerful tool in fields ranging from home maintenance to agriculture, offering both preventive and productive applications.

Are All Psilocybe Spore Prints Purple? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Temperature effects on fungal spore development

Fungal spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in diverse environments until conditions favor germination. However, temperature plays a pivotal role in determining whether these spores develop into mature fungal hyphae. Optimal temperature ranges vary among fungal species, but generally, mesophilic fungi thrive between 20°C and 30°C (68°F and 86°F). For example, *Aspergillus niger*, a common mold, germinates most efficiently at 30°C, while *Penicillium* species prefer slightly cooler temperatures around 25°C. Understanding these preferences is crucial for both controlling fungal growth in unwanted areas and cultivating fungi for industrial or agricultural purposes.

To harness temperature for fungal spore development, consider the following steps. First, identify the specific fungus you are working with, as temperature requirements differ significantly. For instance, thermophilic fungi like *Thermomyces lanuginosus* require temperatures above 45°C (113°F) to germinate, while psychrophilic fungi such as *Geomyces pannorum* can develop at temperatures as low as 4°C (39°F). Second, maintain consistent temperatures within the optimal range using incubators or controlled environments. Fluctuations can delay germination or inhibit growth altogether. For home cultivators, a simple setup like a heated mat or a thermostat-controlled room can suffice for mesophilic fungi.

Despite the importance of optimal temperatures, extreme conditions can either halt or accelerate fungal development in unintended ways. Prolonged exposure to temperatures above 50°C (122°F) typically kills fungal spores, making this a common method for sterilizing equipment. Conversely, suboptimal temperatures below the germination threshold can induce dormancy, allowing spores to survive but not develop. For example, refrigerating fungal cultures at 4°C can preserve spores for months, but they will remain dormant until returned to favorable conditions. This knowledge is particularly useful in food preservation, where controlling temperature prevents spoilage caused by fungal growth.

Practical applications of temperature control in fungal spore development extend beyond the lab. In agriculture, adjusting soil temperature through mulching or irrigation can suppress pathogenic fungi while promoting beneficial species. For instance, maintaining soil temperatures below 15°C (59°F) can inhibit the growth of *Fusarium*, a common crop pathogen. Similarly, in indoor environments, keeping humidity levels low and temperatures outside the optimal range for common molds (e.g., 20°C–30°C) can prevent household fungal infestations. By manipulating temperature strategically, we can either foster or inhibit fungal growth, depending on the desired outcome.

In conclusion, temperature is a critical factor in fungal spore development, dictating whether spores remain dormant, germinate, or perish. Tailoring temperature conditions to specific fungal species ensures successful growth in controlled settings, while understanding temperature thresholds allows for effective fungal management in various contexts. Whether cultivating fungi for biotechnology or preventing mold in homes, precise temperature control is key to achieving the desired results.

Are Spores Viable Haploid Cells? Unraveling Their Biological Significance

You may want to see also

Genetic factors influencing spore maturation into hyphae

Fungal spores are not merely dormant entities awaiting favorable conditions to germinate; their transformation into mature hyphae is a genetically orchestrated process. At the heart of this transition lies a complex interplay of genetic factors that dictate when, where, and how spores develop into the filamentous structures characteristic of fungal growth. Understanding these genetic influences is crucial for fields ranging from agriculture to medicine, as it sheds light on fungal adaptability, pathogenicity, and potential control strategies.

One key genetic factor is the presence of specific genes encoding transcription factors that regulate spore germination. For instance, the *CON* genes in *Aspergillus nidulans* are essential for initiating the developmental switch from spore to hyphal growth. Mutations in these genes can halt germination, highlighting their critical role. Similarly, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the *STE12* gene governs the transition from spore to vegetative growth, demonstrating conservation of such regulatory mechanisms across fungal species. These genes act as molecular switches, responding to environmental cues like nutrient availability, temperature, and pH to activate the germination program.

Epigenetic modifications also play a significant role in spore maturation. Histone acetylation and DNA methylation can influence gene expression patterns during germination, ensuring that the correct set of genes is activated at the right time. For example, in *Neurospora crassa*, histone deacetylases are required for proper spore development and subsequent germination. Disruption of these epigenetic regulators can lead to aberrant hyphal growth or failure to germinate altogether. Such findings underscore the importance of epigenetic control in fine-tuning the genetic program underlying spore-to-hypha transition.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in fungal pathogen management. By targeting the genetic pathways involved in spore germination, researchers can develop fungicides that specifically inhibit this process. For instance, compounds that block the activity of *CON*-like transcription factors could prevent pathogenic fungi from establishing infections. Similarly, understanding epigenetic regulation opens avenues for manipulating fungal growth through environmental interventions, such as altering nutrient availability to suppress germination.

In conclusion, the maturation of fungal spores into hyphae is a genetically driven process governed by transcription factors, epigenetic mechanisms, and environmental responsiveness. Deciphering these genetic factors not only advances our fundamental understanding of fungal biology but also offers practical strategies for controlling fungal growth in agricultural and clinical settings. By targeting these pathways, we can develop more effective and sustainable approaches to managing fungal pathogens and harnessing beneficial fungi.

Exploring Spores: Nature's Ingenious Dispersal Mechanism for Survival and Spread

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungal spores can germinate and develop into mature fungal hyphae under suitable environmental conditions, such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability.

Fungal spores require moisture, a suitable temperature range, oxygen, and a nutrient source to germinate and grow into mature hyphae.

The time varies depending on the fungal species and environmental conditions, but it can range from a few hours to several days for spores to germinate and form mature hyphae.

No, not all fungal spores successfully germinate into mature hyphae. Factors like unfavorable conditions, lack of nutrients, or predation can prevent spore germination.

No, fungal spores require a nutrient source to germinate and grow into mature hyphae, as they are heterotrophic organisms that depend on external organic matter for energy.