Fungal spores are a critical component of the fungal life cycle, serving as both a means of dispersal and a mechanism for survival in adverse conditions. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungal spores is their ability to reproduce asexually, a process that allows fungi to rapidly colonize new environments and adapt to changing conditions. Asexual reproduction in fungi typically involves the formation of specialized structures such as conidia, sporangiospores, or chlamydospores, which are produced through mitosis and can develop into new individuals without the need for fertilization. This mode of reproduction is highly efficient and enables fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from soil and decaying matter to plant and animal hosts. Understanding the mechanisms and implications of asexual spore reproduction is essential for fields such as mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as it sheds light on fungal growth, pathogenicity, and potential control strategies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual |

| Methods of Asexual Reproduction | Budding, Fission, Fragmentation, Sporulation (e.g., conidia, spores) |

| Spore Types | Conidia, Chlamydospores, Oospores, Arthrospores, Blastospores |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, Water, Animals, Human Activities |

| Environmental Factors | Moisture, Temperature, Nutrient Availability |

| Advantages | Rapid Reproduction, Genetic Stability, Survival in Adverse Conditions |

| Examples of Fungi | Aspergillus, Penicillium, Candida, Fusarium, Saccharomyces |

| Significance | Ecological Roles (decomposition), Industrial Applications, Pathogenesis |

| Genetic Diversity | Limited (clonal populations) |

| Adaptability | High (ability to colonize diverse habitats) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Budding in Yeasts: Yeasts reproduce asexually by budding, forming a small outgrowth that detaches as a new cell

- Fragmentation in Fungi: Some fungi break into fragments, each growing into an independent organism without gametes

- Sporulation Process: Fungi produce spores (e.g., conidia) that disperse and grow into new individuals without fertilization

- Vegetative Propagation: Structures like hyphae or mycelium fragments can regenerate into new fungal colonies asexually

- Parthenogenesis in Fungi: Some fungi produce spores from unfertilized gametes, allowing asexual reproduction in certain species

Budding in Yeasts: Yeasts reproduce asexually by budding, forming a small outgrowth that detaches as a new cell

Fungal spores are renowned for their diverse reproductive strategies, but yeasts stand out with a uniquely efficient method: budding. Unlike the dispersal-focused spores of molds or mushrooms, yeasts reproduce asexually by forming a small outgrowth, or bud, directly on the parent cell. This bud gradually enlarges, develops a nucleus, and eventually detaches to become a fully independent cell. This process is not just a curiosity of microbiology; it’s a cornerstone of industries like baking, brewing, and biotechnology, where yeast’s rapid multiplication is harnessed for fermentation and production.

To observe budding in yeasts, a simple experiment can be conducted using a microscope and a nutrient-rich medium like yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) agar. Inoculate the agar with a small amount of yeast (e.g., *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*), incubate at 30°C for 24 hours, and then scrape a small sample onto a slide with a drop of water and a coverslip. Under 400x magnification, you’ll see parent cells with buds in various stages of development—some small and nascent, others nearly the same size as the parent, ready to separate. This hands-on approach not only illustrates budding but also highlights the yeast’s adaptability to resource-rich environments, where asexual reproduction is favored over sexual methods.

From an analytical perspective, budding is a highly regulated process driven by cell cycle checkpoints. The bud emerges at a specific site on the parent cell, determined by internal and external cues. As the bud grows, the nucleus undergoes mitosis, and one daughter nucleus migrates into the bud. Simultaneously, organelles like mitochondria are partitioned between the parent and daughter cell. This precision ensures that each new cell is genetically identical to the parent, a key advantage for maintaining desirable traits in industrial strains. However, this lack of genetic diversity can be a limitation in changing environments, underscoring the trade-offs of asexual reproduction.

For practical applications, understanding budding is crucial for optimizing yeast performance in fermentation processes. In brewing, for instance, controlling factors like temperature (ideally 20–25°C for ale yeasts) and nutrient availability can enhance budding rates, leading to faster alcohol production. Similarly, in baking, ensuring a sufficient supply of sugars and minerals in the dough promotes yeast growth, resulting in better leavening. Conversely, stressors like high ethanol concentrations or low pH can inhibit budding, a cautionary note for industries aiming to maximize yield. By manipulating these conditions, practitioners can harness the full potential of yeast’s asexual reproduction.

Finally, budding in yeasts offers a compelling comparison to other fungal reproductive methods. While molds rely on spore dispersal to colonize new habitats, yeasts prioritize rapid multiplication in situ, a strategy well-suited to stable, nutrient-rich environments. This distinction explains why yeasts dominate in controlled settings like breweries or bakeries, while molds thrive in diverse, unpredictable ecosystems. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, this insight underscores the importance of matching reproductive strategies to specific goals, whether it’s preserving genetic consistency or adapting to new conditions.

Are Spore Servers Down? Current Status and Player Concerns

You may want to see also

Fragmentation in Fungi: Some fungi break into fragments, each growing into an independent organism without gametes

Fungi exhibit a remarkable ability to reproduce asexually through fragmentation, a process where their bodies break into smaller pieces, each capable of growing into a new, independent organism. This method bypasses the need for gametes, making it a highly efficient and rapid means of propagation. For instance, species like *Rhizopus*, a common bread mold, can fragment into smaller mycelial pieces, each of which develops into a genetically identical clone of the parent organism. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in stable environments where the parent fungus has already adapted successfully.

Fragmentation in fungi is not merely a random process but a structured one, often triggered by environmental cues such as physical damage or nutrient availability. When a fungus detects favorable conditions, it may deliberately shed fragments of its mycelium or thallus. These fragments, though small, contain sufficient cellular material to initiate growth. For example, in *Penicillium*, fragments of the mycelium can regenerate into new colonies within days under optimal conditions of moisture and temperature (typically 20–30°C). This adaptability underscores the resilience of fungi in diverse ecosystems.

One practical takeaway from understanding fragmentation is its application in agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers and researchers can exploit this process to cultivate beneficial fungi rapidly. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi, which enhance plant nutrient uptake, can be propagated through fragmentation to improve soil health. To achieve this, a small piece of the fungal mycelium (approximately 1–2 cm in length) can be placed in a nutrient-rich medium, where it will grow into a new colony within 1–2 weeks. This method is cost-effective and scalable, making it ideal for large-scale agricultural projects.

However, fragmentation is not without its limitations. Since it involves the production of clones, genetic diversity is minimal, which can hinder adaptation to changing environments. For example, if a fragmented population of *Aspergillus* encounters a new pathogen, its lack of genetic variation may limit its ability to resist infection. To mitigate this, practitioners should periodically introduce genetic diversity through other reproductive methods, such as sporulation, or by combining fragments from different parent organisms.

In conclusion, fragmentation in fungi is a fascinating and practical asexual reproductive strategy that leverages the organism’s ability to regenerate from small pieces. By understanding and harnessing this process, individuals can propagate beneficial fungi efficiently, whether for agricultural, industrial, or research purposes. However, awareness of its limitations, particularly regarding genetic diversity, ensures its effective and sustainable application. This method exemplifies the ingenuity of fungal biology, offering both simplicity and utility in reproduction.

Are Botulism Spores Dangerous? Understanding Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

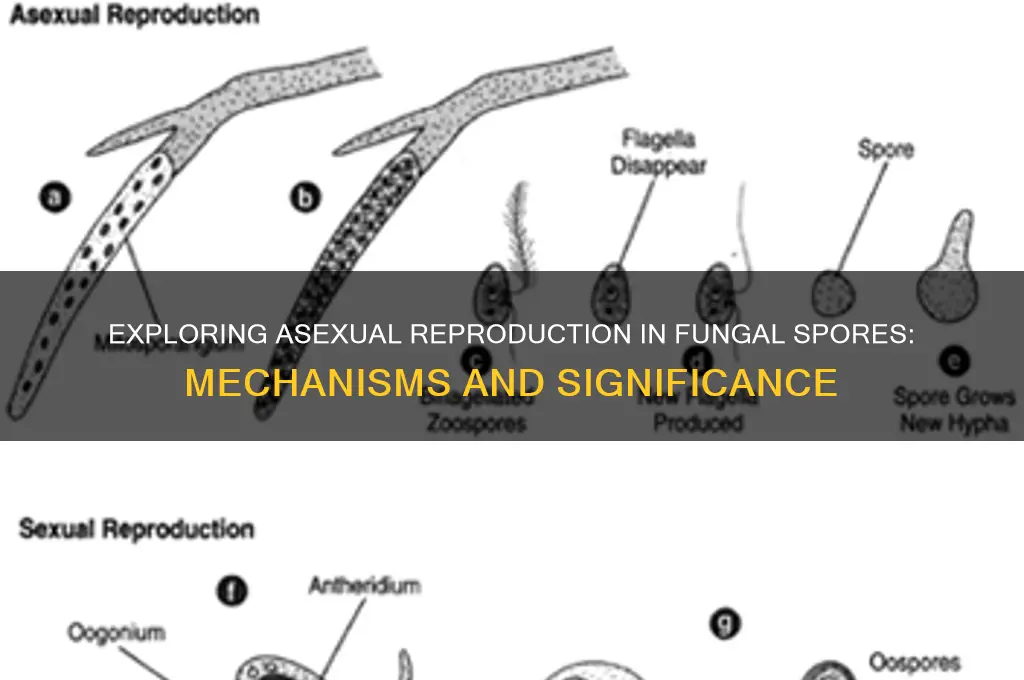

Sporulation Process: Fungi produce spores (e.g., conidia) that disperse and grow into new individuals without fertilization

Fungi have mastered the art of survival through asexual reproduction, a process that hinges on the production and dispersal of spores. One of the most common types of asexual spores is conidia, which are generated by fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. These spores are not the result of fertilization but rather a direct extension of the parent fungus. The sporulation process begins with the development of specialized structures, such as conidiophores, which bear the conidia. Once mature, these spores are released into the environment, where they can land on suitable substrates and grow into new fungal individuals. This method ensures rapid colonization of new habitats, even in the absence of a mate.

The sporulation process is a highly regulated sequence of events, influenced by environmental cues such as nutrient availability, humidity, and temperature. For instance, *Aspergillus niger* produces conidia optimally at temperatures between 28°C and 37°C and high humidity levels. The fungus first forms a network of hyphae, which then differentiate into conidiophores. At the tips of these structures, conidia develop in chains, resembling bunches of grapes. When mature, the spores are dry and lightweight, allowing them to be easily dispersed by air currents. This adaptability in spore production and dispersal is a key reason fungi thrive in diverse ecosystems, from soil to human-made environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the sporulation process is crucial for industries like agriculture and medicine. For example, conidia of *Trichoderma* species are used as biocontrol agents to combat plant pathogens. To maximize their efficacy, conidia are often produced in controlled environments, where factors like light, pH, and nutrient composition are optimized. A common medium for conidia production is potato dextrose agar (PDA), supplemented with trace elements like zinc and manganese. Once harvested, the spores are formulated into powders or suspensions, with concentrations typically ranging from 10^6 to 10^8 spores per gram for effective application. This highlights how knowledge of sporulation can be harnessed for practical benefits.

Comparatively, the asexual sporulation process in fungi contrasts with sexual reproduction, which requires the fusion of gametes and is often more resource-intensive. Asexual spores like conidia offer a quick and efficient means of propagation, particularly in stable environments where genetic diversity is less critical. However, this method also has limitations. Since the offspring are genetically identical to the parent, they may lack the resilience to adapt to sudden environmental changes. For instance, a population of *Penicillium* spores produced asexually might struggle if exposed to a new fungicide, whereas sexually produced spores could potentially carry mutations that confer resistance.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a testament to fungi’s evolutionary ingenuity. By producing spores like conidia, fungi bypass the need for fertilization, ensuring rapid and widespread reproduction. This mechanism is not only a survival strategy but also a resource for human applications, from biocontrol to biotechnology. However, its efficiency comes with trade-offs, such as reduced genetic diversity. For anyone working with fungi—whether in research, agriculture, or industry—grasping the intricacies of sporulation is essential for harnessing its potential while mitigating its limitations.

Can Coffee Kill Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind This Claim

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$3.99

Vegetative Propagation: Structures like hyphae or mycelium fragments can regenerate into new fungal colonies asexually

Fungi possess a remarkable ability to regenerate from fragmented vegetative structures, a process known as vegetative propagation. Unlike spore-based reproduction, which relies on specialized cells, this method leverages the inherent resilience of hyphae and mycelium. When a fragment of these structures is separated from the parent colony—whether by physical disruption, environmental factors, or human intervention—it retains the genetic material and metabolic capacity to initiate a new colony. This asexual mechanism ensures rapid proliferation without the need for mating or genetic recombination, making it a highly efficient survival strategy in stable environments.

Consider the practical implications for mycologists and cultivators. To propagate fungi vegetatively, one can carefully excise a small portion of mycelium (approximately 1–2 cm in diameter) from a healthy colony using a sterile scalpel or blade. This fragment should then be transferred to a nutrient-rich substrate, such as agar or grain spawn, under aseptic conditions to prevent contamination. Within days to weeks, depending on the species, the fragment will develop into a new, genetically identical colony. For example, *Ophiocordyceps sinensis*, a fungus prized in traditional medicine, is often cultivated using mycelium fragments due to the challenges of spore-based propagation.

While vegetative propagation offers advantages in speed and genetic consistency, it is not without limitations. Over time, reliance on this method can reduce genetic diversity, making fungal populations more susceptible to diseases or environmental changes. Additionally, fragmented structures may carry contaminants from the parent colony, necessitating rigorous sterilization protocols. For instance, soaking mycelium fragments in a 10% hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 minutes can reduce microbial contamination without harming fungal viability. Balancing these trade-offs requires careful planning and monitoring.

Comparatively, vegetative propagation stands in stark contrast to spore-based reproduction, which disperses genetically diverse offspring over long distances. However, in controlled environments like laboratories or farms, the predictability and speed of vegetative propagation make it invaluable. For hobbyists or small-scale cultivators, this method allows for the preservation and expansion of rare or desirable strains without specialized equipment. A simple setup—a laminar flow hood, sterile containers, and basic substrates—can yield consistent results with minimal investment.

In conclusion, vegetative propagation through hyphae or mycelium fragments exemplifies the adaptability of fungi, offering a straightforward yet powerful tool for asexual reproduction. By understanding and harnessing this mechanism, practitioners can efficiently cultivate fungi for research, agriculture, or industry. However, success hinges on meticulous technique and awareness of potential pitfalls. Whether preserving a prized strain or scaling up production, this method bridges the gap between scientific principle and practical application, showcasing the ingenuity of both fungi and those who study them.

Understanding Mold Spores Lifespan: How Long Do They Survive?

You may want to see also

Parthenogenesis in Fungi: Some fungi produce spores from unfertilized gametes, allowing asexual reproduction in certain species

Fungi exhibit a remarkable diversity in reproductive strategies, and parthenogenesis stands out as a unique mechanism where spores develop from unfertilized gametes. This process bypasses the need for mating, enabling certain fungal species to reproduce asexually under specific conditions. For instance, some species of the genus *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* can produce viable spores through parthenogenesis, ensuring survival even in the absence of compatible mates. This adaptability highlights fungi’s evolutionary ingenuity in colonizing diverse environments.

Analyzing the mechanism, parthenogenesis in fungi involves the direct development of spores from female gametangia without fertilization. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires genetic recombination, parthenogenetic spores are genetically identical to the parent, preserving traits that may be advantageous in stable environments. However, this lack of genetic diversity limits their ability to adapt to changing conditions, making parthenogenesis a trade-off between rapid reproduction and long-term resilience. Researchers often study this process in controlled environments, such as agar plates with specific nutrient compositions, to observe how fungi respond to stressors like nutrient scarcity or temperature fluctuations.

From a practical standpoint, understanding parthenogenesis in fungi has significant implications for industries like agriculture and medicine. For example, fungal pathogens that reproduce parthenogenetically can rapidly spread in crops, causing widespread damage. Farmers can mitigate this by rotating crops or using fungicides with active ingredients like chlorothalonil or mancozeb, which disrupt spore formation. Conversely, beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* species, which can suppress plant pathogens, are cultivated using parthenogenesis to ensure consistent production of effective biocontrol agents.

Comparatively, parthenogenesis in fungi differs from similar processes in other organisms, such as aphids or certain reptiles, due to the unique structure of fungal spores. Fungal spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving extreme conditions like desiccation or radiation, making them ideal for asexual reproduction. This resilience is attributed to their thick cell walls composed of chitin and glucans, which provide structural integrity. In contrast, parthenogenetic eggs in animals lack such protective features, limiting their survival outside controlled environments.

In conclusion, parthenogenesis in fungi is a fascinating adaptation that underscores their versatility in reproduction. By producing spores from unfertilized gametes, certain species ensure survival in challenging conditions, though at the cost of genetic diversity. This mechanism has practical applications in agriculture and biotechnology, offering both challenges and opportunities. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, studying parthenogenesis provides valuable insights into fungal biology and its broader ecological impact.

Unveiling the Truth: Are Mold Spores Toxic to Your Health?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many fungal spores can reproduce asexually through processes like budding, fragmentation, or spore formation (e.g., conidia or sporangiospores).

Common methods include budding (e.g., in yeast), fragmentation (breaking into smaller pieces that grow into new fungi), and spore production (e.g., conidia in molds or sporangiospores in some fungi).

No, not all fungal spores reproduce asexually. Some fungi produce sexual spores (e.g., asci or basidiospores) through meiosis, while others are primarily asexual or can switch between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on conditions.