Fungal spores are a critical component of the fungal life cycle, serving as both a means of dispersal and a survival mechanism. While many fungi reproduce asexually through spore formation, a significant number of species also have the capability to reproduce sexually. Sexual reproduction in fungi involves the fusion of compatible hyphae or gametes, leading to the formation of specialized structures like zygospores, ascospores, or basidiospores. These sexually produced spores often play a vital role in genetic diversity, allowing fungi to adapt to changing environments and resist stressors. Understanding whether and how fungal spores can reproduce sexually is essential for comprehending fungal biology, ecology, and their impact on ecosystems and human activities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sexual Reproduction | Many fungal spores can reproduce sexually under favorable conditions. |

| Process | Involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals, resulting in a diploid zygote. |

| Types of Spores | Zygospores, ascospores, and basidiospores are common sexually produced spores. |

| Zygospores | Formed by the fusion of two gametangia (e.g., in Zygomycota), typically thick-walled and resistant to harsh conditions. |

| Ascospores | Produced within a sac-like structure called an ascus (e.g., in Ascomycota), often released through a pore. |

| Basidiospores | Formed on a club-shaped structure called a basidium (e.g., in Basidiomycota), commonly found in mushrooms. |

| Pheromone Signaling | Fungi use pheromones to identify compatible mates and initiate sexual reproduction. |

| Plasmodium Fusion | In some fungi (e.g., Myxomycetes), plasmodia fuse to form a diploid zygote. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sexual reproduction is often induced by environmental cues like nutrient scarcity, temperature changes, or light. |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual reproduction promotes genetic recombination, increasing diversity and adaptability. |

| Asexual vs. Sexual | Many fungi can switch between asexual (e.g., conidia) and sexual reproduction depending on conditions. |

| Examples | Mushrooms, yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and molds (e.g., Neurospora crassa). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fungal spore sexual compatibility: Understanding genetic and environmental factors influencing successful mating between compatible fungal spores

- Karyogamy process: Fusion of haploid nuclei during sexual reproduction, forming a diploid zygote in fungi

- Ascospores and basidiospores: Specialized sexual spores produced in asci and basidia, respectively, in fungi

- Meiosis in fungi: Reduction division in sexual reproduction, generating genetic diversity in fungal spores

- Environmental triggers for sexuality: Factors like nutrient scarcity or stress inducing sexual reproduction in fungi

Fungal spore sexual compatibility: Understanding genetic and environmental factors influencing successful mating between compatible fungal spores

Fungal spores, often perceived as asexual entities, indeed possess the capacity for sexual reproduction under specific conditions. This process, however, is not a simple encounter but a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for fields ranging from agriculture to medicine, where fungal mating can lead to genetic diversity, pathogenicity, or beneficial traits.

Fungal species exhibit diverse mating systems, from heterothallic (requiring two compatible partners) to homothallic (self-fertile). Compatibility is primarily governed by mating-type loci, which encode proteins involved in recognition and signaling. For instance, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, the a and α loci determine mating types, with successful mating occurring only between opposite types. Environmental cues such as nutrient availability, pH, and temperature further modulate this process. For example, in *Neurospora crassa*, nitrogen starvation triggers the formation of sexual structures (perithecia), while optimal mating occurs at pH 5.5–6.5.

To study sexual compatibility, researchers employ techniques like genetic crosses and molecular markers. A practical tip for laboratory experiments: maintain cultures at 25°C and use minimal media (e.g., 1% glucose, 0.5% ammonium sulfate) to induce mating in species like *Aspergillus nidulans*. Caution: avoid contamination by sterilizing equipment and using antibiotics (e.g., 100 µg/mL penicillin) in growth media. Analyzing progeny through PCR or sequencing can confirm successful mating and identify genetic recombination events.

Environmental factors act as both triggers and barriers to fungal mating. Light, humidity, and carbon sources play pivotal roles. For instance, in *Coprinopsis cinerea*, blue light accelerates mating, while high humidity (80–90%) is essential for spore germination in *Fusarium graminearum*. Comparative studies reveal that while some fungi, like *Cryptococcus neoformans*, mate efficiently in nutrient-rich conditions, others, such as *Ustilago maydis*, require minimal nutrients. A persuasive argument here is that manipulating these factors could control fungal populations in agricultural settings, reducing crop diseases caused by sexually reproducing pathogens.

The takeaway is clear: sexual compatibility in fungal spores is a finely tuned process influenced by genetics and environment. By deciphering these mechanisms, scientists can develop strategies to either promote beneficial mating (e.g., in biocontrol fungi) or inhibit harmful mating (e.g., in pathogenic fungi). Practical applications include breeding programs for improved mushroom strains or targeted fungicides that disrupt mating signals. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, understanding these dynamics opens doors to innovative solutions in fungal biology and beyond.

Gymnosperms vs. Spores: Unraveling the Evolutionary Timeline of Plants

You may want to see also

Karyogamy process: Fusion of haploid nuclei during sexual reproduction, forming a diploid zygote in fungi

Fungal spores, often associated with asexual reproduction, can indeed participate in sexual processes under specific conditions. The karyogamy process is a pivotal event in this sexual cycle, marking the fusion of haploid nuclei to form a diploid zygote. This mechanism is essential for genetic diversity and adaptation in fungi, ensuring their survival across diverse environments. Understanding karyogamy provides insights into fungal biology and highlights the complexity of their reproductive strategies.

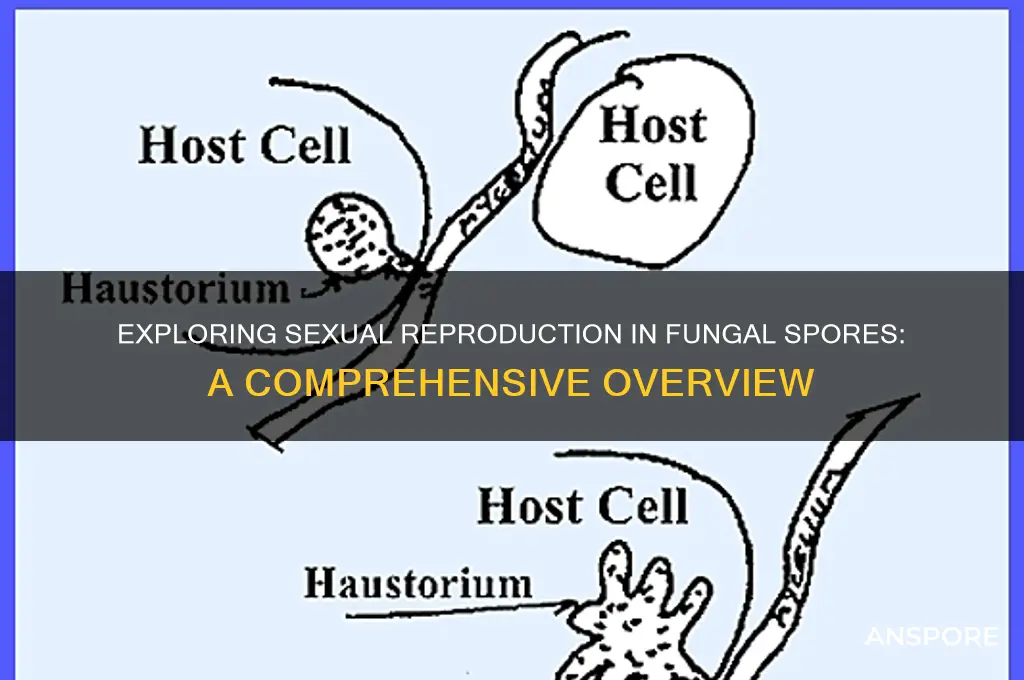

The karyogamy process begins with the conjugation of haploid cells, typically from compatible mating types. In fungi like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), this involves the fusion of two haploid cells (a and α) through a specialized structure called a shmoo. Once the cell membranes merge, the haploid nuclei migrate toward each other within the newly formed dikaryotic cell. This migration is facilitated by cytoskeletal elements, ensuring precise alignment before fusion. The timing of karyogamy is tightly regulated, often triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient scarcity or pheromone signaling, which activate specific genes like *KAR3* and *CIK1* to guide the process.

During karyogamy, the fusion of haploid nuclei results in a diploid nucleus, a critical step in forming a zygote. This diploid state allows for genetic recombination during meiosis, generating spores with novel genetic combinations. For example, in *Aspergillus nidulans*, karyogamy occurs within a specialized structure called the ascus, where the diploid zygote undergoes meiosis to produce haploid ascospores. These ascospores can then disperse and germinate, perpetuating the fungal life cycle. The efficiency of karyogamy is crucial, as failures in nuclear fusion can lead to inviable offspring, underscoring its role as a bottleneck in sexual reproduction.

Practical applications of understanding karyogamy extend to biotechnology and agriculture. For instance, manipulating karyogamy in yeast can enhance the production of biofuels or pharmaceuticals by optimizing genetic diversity. In plant pathology, disrupting this process in pathogenic fungi could serve as a targeted control strategy, reducing crop losses without harming beneficial microorganisms. Researchers often use genetic tools like CRISPR-Cas9 to study karyogamy genes, offering precise insights into their function. For hobbyists or educators, observing karyogamy in yeast under a microscope can be a fascinating experiment, requiring only basic lab equipment and mating-type strains.

In summary, the karyogamy process is a cornerstone of fungal sexual reproduction, driving genetic innovation through the fusion of haploid nuclei. Its regulation, mechanisms, and outcomes reveal the sophistication of fungal life cycles and their adaptability. Whether in research, industry, or education, understanding karyogamy opens doors to harnessing fungal biology for practical purposes while appreciating its evolutionary significance.

Can You See Mold Spores? Unveiling the Invisible Threat in Your Home

You may want to see also

Ascospores and basidiospores: Specialized sexual spores produced in asci and basidia, respectively, in fungi

Fungi, often overlooked in the grand tapestry of life, possess a remarkable reproductive strategy centered around specialized sexual spores. Among these, ascospores and basidiospores stand out as key players, each produced in unique structures that underscore the diversity and complexity of fungal reproduction. Ascospores develop within sac-like structures called asci, typically found in Ascomycota, one of the largest fungal phyla. Basidiospores, on the other hand, are borne on club-shaped structures known as basidia, characteristic of Basidiomycota, which includes mushrooms and rusts. These spores are not merely reproductive units; they are the culmination of intricate sexual processes that ensure genetic diversity and survival in varying environments.

Consider the lifecycle of ascospores. Formed through a process called ascogenesis, these spores are the product of sexual fusion within the ascus. This begins with the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals, resulting in a diploid zygote. The zygote then undergoes meiosis, followed by mitosis, to produce eight haploid ascospores. These spores are often forcibly ejected from the ascus, dispersing widely to colonize new habitats. For example, the fungus *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) produces ascospores under specific environmental conditions, such as nutrient limitation, showcasing the adaptability of this reproductive mechanism. Practical tip: To observe ascospores, mount a sample of an ascocarp (fruiting body) on a microscope slide and look for the sac-like asci containing the spores.

Basidiospores, in contrast, are produced on the external surface of basidia, a feature that distinguishes them from ascospores. The basidium typically supports four spores, each attached by a slender projection called a sterigma. When mature, the basidiospores are released, often with the aid of a droplet of fluid that forms at the sterigma tip, propelling the spore into the air. This mechanism, known as ballistospore discharge, is highly efficient for dispersal. For instance, the common mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* relies on basidiospores to propagate, with each basidium producing spores capable of traveling several centimeters in still air. Caution: Handling basidiocarps (mushroom fruiting bodies) requires care, as some species produce toxic compounds or allergens.

Comparing ascospores and basidiospores reveals both similarities and differences in their ecological roles. Both are products of sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic recombination and adaptability. However, their structures and dispersal mechanisms differ significantly. Ascospores are often more resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions, while basidiospores are optimized for rapid dispersal. This specialization reflects the diverse habitats fungi occupy, from soil and decaying matter to living plants. For researchers or enthusiasts, understanding these differences can aid in identifying fungal species and predicting their behavior in various environments.

In practical applications, knowledge of ascospores and basidiospores is invaluable. For example, in agriculture, managing fungal pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae* (rice blast fungus, an Ascomycota) requires understanding its ascospore production and dispersal patterns. Similarly, in forestry, controlling basidiomycete pathogens such as *Armillaria* spp. (honey fungus) involves targeting basidiospore release from their rhizomorphs. Takeaway: By studying these specialized spores, we gain insights into fungal ecology and develop strategies to mitigate their negative impacts or harness their benefits, whether in food production, medicine, or environmental management.

Are Spores an Aerosol? Exploring the Science Behind Airborne Particles

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Meiosis in fungi: Reduction division in sexual reproduction, generating genetic diversity in fungal spores

Fungal spores are not merely agents of dispersal; they are the products of a sophisticated reproductive strategy that ensures survival and adaptability. Among the various mechanisms fungi employ, sexual reproduction stands out for its role in generating genetic diversity. Central to this process is meiosis, a specialized cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid spores capable of combining genetic material from two parents. This reduction division is not just a biological curiosity—it is a cornerstone of fungal evolution, enabling species to respond to environmental pressures and resist threats like fungicides.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus nidulans*, a model fungus for studying meiosis. When conditions trigger sexual reproduction, haploid cells from two compatible individuals fuse, forming a diploid zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis, a two-stage division process that first separates homologous chromosomes (Meiosis I) and then sister chromatids (Meiosis II). The result is four haploid spores, each genetically distinct due to crossing over during prophase I. This genetic shuffling is critical for fungi, which often face static environments where adaptability is key. For instance, in agricultural settings, fungi like *Magnaporthe oryzae* (rice blast fungus) rely on meiosis to evolve resistance to fungicides, underscoring the practical implications of this process.

To visualize meiosis in fungi, imagine a baker kneading dough to mix ingredients—except here, the "ingredients" are genetic traits. During prophase I, homologous chromosomes align and exchange segments, a process called recombination. This step is akin to the baker folding in different flavors, creating unique combinations. By the end of meiosis, the resulting spores carry novel genetic profiles, increasing the population’s resilience. For researchers, understanding this mechanism is crucial; manipulating meiotic recombination could lead to breakthroughs in controlling fungal pathogens or enhancing beneficial fungi in biotechnology.

Practical applications of meiotic studies in fungi extend beyond academia. In brewing, for example, yeast (*Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) undergoes meiosis to produce spores that can adapt to varying fermentation conditions. Brewers often select strains with specific genetic traits, such as tolerance to high alcohol concentrations, by exploiting this natural diversity. Similarly, in mycoremediation—using fungi to clean up pollutants—genetically diverse spores enhance the efficiency of toxin breakdown. To harness these benefits, scientists recommend controlled environments that mimic natural triggers for sexual reproduction, such as nutrient limitation or temperature shifts, to induce meiosis in laboratory settings.

In conclusion, meiosis in fungi is more than a biological mechanism—it is a survival strategy. By generating genetic diversity through reduction division, fungi ensure their offspring are equipped to thrive in unpredictable environments. Whether combating pathogens or optimizing industrial processes, understanding and manipulating this process offers tangible benefits. For those working with fungi, the takeaway is clear: meiosis is not just about reproduction; it is about innovation encoded in the very DNA of fungal spores.

Understanding Mold Spores: Causes, Health Risks, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for sexuality: Factors like nutrient scarcity or stress inducing sexual reproduction in fungi

Fungi, often thriving in environments where resources are unpredictable, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to ensure survival. Among these is the ability to switch from asexual to sexual reproduction when conditions demand it. Environmental stressors such as nutrient scarcity, temperature fluctuations, or physical damage act as triggers, prompting fungi to produce sexual spores. This adaptive strategy ensures genetic diversity, which is crucial for adapting to changing environments and resisting pathogens. For instance, *Neurospora crassa*, a model fungus, initiates sexual reproduction when nitrogen levels drop below 10 mM, a threshold that signals resource limitation.

To understand how nutrient scarcity induces sexuality, consider the role of carbon and nitrogen availability. When carbon sources like glucose are abundant, fungi typically favor asexual reproduction, which is faster and less energy-intensive. However, when carbon is scarce, and nitrogen levels are insufficient, fungi like *Aspergillus nidulans* shift to sexual reproduction. This shift is regulated by signaling pathways, such as the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) pathway, which senses nutrient levels and activates sexual development genes. Practical tip: In laboratory settings, reducing glucose concentration to 0.1% (w/v) and maintaining a C:N ratio below 5:1 can reliably induce sexual reproduction in many fungal species.

Stress, whether from desiccation, UV radiation, or mechanical injury, also triggers sexual reproduction in fungi. For example, *Fusarium graminearum*, a crop pathogen, produces sexual spores (ascospores) in response to prolonged drought. This response is mediated by stress-activated MAP kinase (MAPK) pathways, which detect cellular damage and initiate sexual development. Comparative analysis reveals that while asexual spores are optimized for rapid dispersal, sexual spores are more resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions for years. This trade-off highlights the strategic importance of stress-induced sexuality in fungal life cycles.

A persuasive argument for studying these triggers lies in their agricultural and medical implications. Fungal pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae* (rice blast) and *Candida albicans* (human pathogen) often become more virulent after sexual reproduction, as it generates genetic diversity that can overcome host defenses. By identifying and manipulating environmental triggers, such as nutrient availability or stress levels, researchers could develop strategies to disrupt sexual reproduction in harmful fungi. For instance, maintaining high nitrogen levels in soil might suppress sexual reproduction in crop pathogens, reducing disease outbreaks.

In conclusion, environmental triggers like nutrient scarcity and stress are not mere challenges for fungi but catalysts for sexual reproduction. These mechanisms ensure survival and adaptability in dynamic ecosystems. By studying these triggers, scientists can unlock new ways to control fungal pathogens and harness beneficial fungi. Practical takeaway: Monitor nutrient levels and stress factors in agricultural or clinical settings to predict and manage fungal sexual reproduction, potentially mitigating disease and improving outcomes.

Mastering Spore Syringe Creation: A Step-by-Step DIY Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many fungal spores can reproduce sexually through processes like plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis, leading to the formation of genetic diversity.

Most fungi, including Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, and Zygomycetes, have spores capable of sexual reproduction under favorable conditions.

Fungal spores can fuse with compatible spores or structures (e.g., gametangia) to combine genetic material, resulting in the production of sexually derived spores like ascospores or basidiospores.

No, not all fungal spores can reproduce sexually. Some fungi are asexual or have lost the ability to reproduce sexually, relying solely on vegetative or asexual spore production.