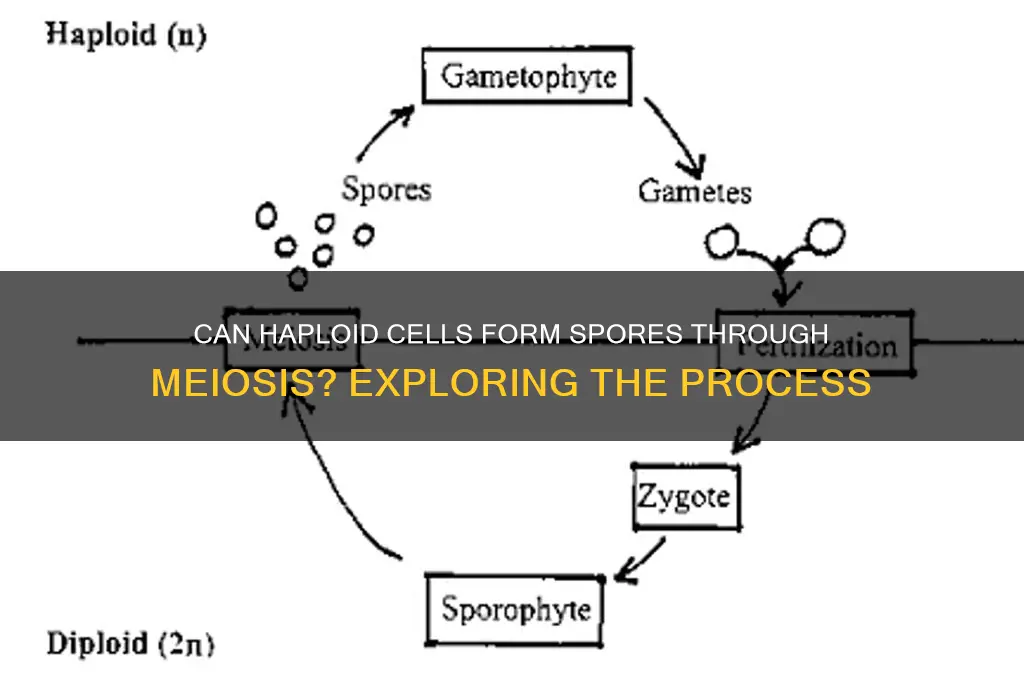

Haploid cells, which contain a single set of chromosomes, play a crucial role in the life cycles of many organisms, particularly in fungi, plants, and some algae. One of the key processes involving haploid cells is sporulation, where spores are formed as a means of reproduction or survival. Meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, is central to this process. In organisms like fungi and plants, haploid cells can indeed undergo meiosis to form spores, but this typically occurs in a diploid phase of their life cycle, where the cell first becomes diploid through fertilization or karyogamy. The resulting diploid cell then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, which can later germinate and grow into new haploid individuals. Thus, while haploid cells themselves do not directly form spores through meiosis, they are integral to the life cycles where meiosis leads to spore formation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Involved | Meiosis |

| Cell Type Before Meiosis | Diploid (2n) |

| Cell Type After Meiosis | Haploid (n) |

| Can Haploid Cells Undergo Meiosis | No, haploid cells cannot undergo meiosis; they can only undergo mitosis or directly form spores in some organisms |

| Spore Formation in Haploid Cells | In certain organisms (e.g., fungi, plants), haploid cells can directly form spores via mitosis or specialized processes like sporulation, but not via meiosis |

| Meiosis Purpose | Reduces chromosome number from diploid to haploid for sexual reproduction |

| Spores Formed by Meiosis | Spores (e.g., in plants and fungi) are typically formed from diploid cells undergoing meiosis, not from haploid cells |

| Examples of Haploid Spore Formation | Fungi (e.g., yeast) form haploid spores via mitosis after a haploid phase; plants (e.g., ferns) form haploid spores via meiosis in diploid sporophyte generation |

| Key Distinction | Haploid cells do not undergo meiosis; spores formed by meiosis originate from diploid cells |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Meiosis in Haploid Cells: Process Overview

Haploid cells, by definition, contain a single set of chromosomes, which raises the question: can they undergo meiosis, a process typically associated with reducing diploid cells to haploid? The answer lies in understanding the unique context of organisms like fungi and some algae, where haploid cells can indeed form spores through a modified meiotic process. This mechanism is crucial for survival and propagation in environments that demand rapid adaptation and dispersal.

In fungi, for example, haploid cells can undergo a specialized form of meiosis to form spores, even though they are already haploid. This process, often termed "haploid meiosis," serves a different purpose than the traditional meiosis in diploid organisms. Instead of reducing chromosome number, it promotes genetic diversity through recombination. The steps involve DNA replication, followed by two rounds of cell division (Meiosis I and Meiosis II), resulting in four genetically distinct haploid spores. This ensures that even in stable haploid states, organisms can adapt to changing conditions by shuffling genetic material.

One practical example is the yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, where haploid cells of opposite mating types can fuse to form a diploid cell, which then undergoes meiosis to produce spores. However, in some fungi like *Aspergillus*, haploid cells directly enter meiosis without prior diploid formation. This direct approach highlights the flexibility of meiotic processes across species. For researchers or educators, observing spore formation in haploid fungi under a microscope (using a 40x objective lens) can provide a tangible demonstration of this phenomenon.

A critical takeaway is that meiosis in haploid cells is not redundant but rather a strategic adaptation. It allows organisms to maintain genetic diversity without the need for a diploid phase, which can be energetically costly in certain environments. For instance, in nutrient-poor soils, fungi rely on spore formation to disperse and colonize new areas efficiently. Understanding this process has practical applications in biotechnology, such as optimizing fungal strains for industrial fermentation or biocontrol agents.

In summary, while meiosis is traditionally linked to diploid cells, haploid cells in certain organisms employ a modified version of this process to form spores. This mechanism underscores the versatility of cellular reproduction strategies and their ecological significance. Whether in a classroom or a lab, exploring this process offers valuable insights into the adaptability of life at the cellular level.

Effective Mold Removal: Clean Safely Without Spreading Spores

You may want to see also

Sporulation Mechanisms in Fungi and Algae

Haploid cells, by definition, contain a single set of chromosomes, and their role in spore formation varies significantly across different organisms. In the context of fungi and algae, sporulation mechanisms are intricate processes that ensure survival and propagation under diverse environmental conditions. Unlike diploid cells, which typically undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores, haploid cells in these organisms employ unique strategies to form spores, often bypassing the need for meiosis altogether.

In fungi, sporulation is a critical survival mechanism, particularly in species like *Aspergillus* and *Neurospora*. These organisms, despite being predominantly haploid in their vegetative state, produce spores through mitosis rather than meiosis. For instance, conidia, the most common type of fungal spores, are formed via repeated mitotic divisions at the tips of specialized structures called conidiophores. This asexual mode of sporulation allows for rapid proliferation and adaptation to changing environments. However, fungi also engage in sexual reproduction under specific conditions, where haploid cells of opposite mating types fuse to form a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, such as asci or basidiospores. This dual strategy highlights the flexibility of fungal sporulation mechanisms.

Algae, on the other hand, exhibit a broader range of sporulation mechanisms, reflecting their diverse evolutionary histories and ecological niches. In green algae like *Chlamydomonas*, haploid cells can directly form spores through mitosis, similar to fungal conidia. However, some algae, such as *Ulva* (sea lettuce), alternate between haploid and diploid phases in their life cycles. During the haploid phase, cells can produce spores via mitosis, while the diploid phase involves meiosis to generate haploid spores. This alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity and resilience in algal populations. Notably, red algae like *Porphyra* have a more complex life cycle, where haploid spores (carpospores) are produced following the fusion of gametes and subsequent mitotic divisions, rather than meiosis.

A key takeaway from these mechanisms is the adaptability of sporulation processes in fungi and algae. While meiosis is central to sexual reproduction and genetic recombination, haploid cells in these organisms often rely on mitosis for spore formation, ensuring rapid and efficient propagation. This distinction underscores the evolutionary advantages of maintaining a haploid lifestyle, particularly in environments where quick responses to stress or resource scarcity are essential.

Practical applications of understanding sporulation mechanisms extend to biotechnology and agriculture. For example, optimizing conidia production in fungi like *Trichoderma* enhances their use as biocontrol agents against plant pathogens. Similarly, manipulating sporulation in algae can improve biomass yields for biofuel production. By studying these processes, researchers can develop strategies to harness the unique capabilities of fungi and algae, contributing to sustainable solutions in various industries.

Ringworm Spores: Are They Lurking Everywhere in Your Environment?

You may want to see also

Role of Meiosis in Haploid Life Cycles

Meiosis is a cornerstone of sexual reproduction, but its role in haploid life cycles is often misunderstood. Unlike diploid organisms, where meiosis reduces chromosome number to produce gametes, haploid organisms already possess a single set of chromosomes. So, how does meiosis function in this context? The answer lies in the formation of spores, specialized cells that ensure survival and dispersal. In haploid life cycles, meiosis generates genetic diversity among spores, which then develop into new individuals through mitosis. This process is critical in fungi, algae, and some plants, where environmental pressures demand adaptability.

Consider the life cycle of a fungus like *Penicillium*. Here, haploid spores (conidia) are produced asexually through mitosis, but when conditions deteriorate, the fungus switches to sexual reproduction. Meiosis occurs in specialized structures called gametangia, producing haploid gametes that fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis to restore the haploid state, generating spores with novel genetic combinations. This dual role of meiosis—both in creating genetic diversity and maintaining the haploid phase—highlights its versatility in haploid organisms.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this process is vital for industries like agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, in breeding programs for haploid plants (e.g., certain algae or ferns), controlling meiosis can enhance trait variability, leading to hardier crops. Similarly, in fungal fermentation processes, manipulating spore formation through meiosis can optimize yield and product quality. Researchers often use temperature and nutrient cues to trigger meiosis, mimicking natural environmental stresses. For example, exposing *Aspergillus* cultures to 30°C and nitrogen depletion can induce sporulation, a technique widely applied in enzyme production.

Comparatively, the role of meiosis in haploid life cycles contrasts sharply with its function in diploid organisms. In diploids, meiosis is a one-time event leading to gamete formation, whereas in haploids, it is cyclical, intertwined with mitosis to sustain the life cycle. This distinction underscores the adaptability of meiosis across different biological systems. While diploid organisms rely on meiosis for reproduction, haploid organisms use it for survival, ensuring genetic resilience in the face of changing environments.

In conclusion, meiosis in haploid life cycles is not merely a reproductive mechanism but a survival strategy. By generating genetically diverse spores, it equips organisms to thrive in unpredictable conditions. Whether in fungal colonies or algal blooms, this process exemplifies nature’s ingenuity. For scientists and practitioners, mastering this dynamic offers opportunities to innovate in fields ranging from food production to medicine. The next time you encounter a moldy orange or a fern frond, remember: meiosis is quietly at work, shaping life’s diversity.

Ethanol's Power: Can 7% Concentration Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differences Between Spores and Gametes Formation

Haploid cells, with their single set of chromosomes, play distinct roles in the life cycles of organisms, particularly in the formation of spores and gametes. While both processes involve haploid cells, the mechanisms, purposes, and outcomes differ significantly. Understanding these differences is crucial for grasping the diversity of reproductive strategies in the biological world.

Mechanisms of Formation: Meiosis and Beyond

Spores are typically formed through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid. In organisms like fungi and plants, sporulation occurs as a survival mechanism, often in response to environmental stressors. For instance, in *Aspergillus*, a fungus, haploid spores are produced via meiosis and subsequent mitotic divisions, ensuring genetic diversity and resilience. Gametes, on the other hand, are also haploid but are specifically produced for sexual reproduction. In animals, meiosis directly generates gametes (sperm and eggs), while in plants, it occurs within specialized structures like anthers and ovules. The key distinction lies in the immediate purpose: spores are for dispersal and survival, whereas gametes are for genetic recombination.

Environmental Triggers and Timing

Spores are often formed in response to adverse conditions, such as nutrient depletion or desiccation. For example, *Bacillus* bacteria produce endospores during starvation, which can remain dormant for years. Gametes, however, are typically produced under favorable conditions to maximize the chances of successful fertilization. In humans, gamete production (spermatogenesis and oogenesis) is hormonally regulated and occurs during reproductive years, usually from puberty to menopause in females. This contrast highlights how spores serve as a protective measure, while gametes are tied to the continuation of the species under optimal conditions.

Genetic Diversity and Function

Spores frequently undergo genetic recombination during meiosis, increasing diversity within a population. In ferns, for instance, haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes through mitosis. This two-step process amplifies genetic variation. Gametes, while also haploid, are the direct result of meiosis and carry half the genetic material of the parent. Their primary function is to fuse during fertilization, restoring the diploid state. This difference underscores the role of spores in survival and adaptation, whereas gametes are central to sexual reproduction and genetic mixing.

Practical Implications and Examples

For gardeners, understanding spore formation is essential for propagating plants like mosses or ferns, where spores are sown to grow new individuals. In contrast, knowledge of gamete formation is critical in assisted reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), where mature gametes are combined outside the body. For example, in IVF, human oocytes are harvested after hormonal stimulation, and sperm are prepared for optimal fertilization. These applications demonstrate how the distinct processes of spore and gamete formation have tangible impacts in horticulture and medicine.

Takeaway: Purpose Drives Process

The formation of spores and gametes, though both involving haploid cells, is driven by different biological imperatives. Spores are a survival strategy, enabling organisms to endure harsh conditions and disperse widely. Gametes, however, are the cornerstone of sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity and the continuity of species. Recognizing these differences not only enriches our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications in fields ranging from agriculture to healthcare.

Moss Spores vs. Sporangium: Unraveling the Tiny Reproductive Structures

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers for Haploid Sporulation

Haploid cells, already possessing a single set of chromosomes, cannot undergo meiosis to form spores since meiosis is inherently a process that reduces diploid cells to haploid. However, certain haploid organisms, such as fungi and algae, can still form spores through specialized asexual or sexual processes triggered by environmental cues. Understanding these triggers is crucial for manipulating sporulation in biotechnology, agriculture, and ecological studies.

Nutrient Deprivation: The Universal Signal

One of the most potent environmental triggers for haploid sporulation is nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. For instance, in the yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, starvation induces haploid cells to form asexual spores (ascospores) via a process called sporulation. Studies show that reducing glucose concentrations to below 0.5% (w/v) in the growth medium accelerates sporulation within 12–16 hours. Similarly, in the filamentous fungus *Aspergillus nidulans*, nitrogen limitation activates the *brlA* gene, a master regulator of spore formation. Practical tip: To induce sporulation in lab cultures, gradually decrease nutrient availability over 24 hours, ensuring cells are in the exponential growth phase before initiating starvation.

Osmotic Stress: A Double-Edged Sword

High salinity or drought conditions create osmotic stress, another trigger for haploid sporulation in organisms like *Chlamydomonas reinhardtii*, a green alga. When exposed to 200–300 mM NaCl, *C. reinhardtii* cells form zygospores within 48 hours as a survival mechanism. However, prolonged exposure to >500 mM NaCl inhibits sporulation, highlighting the importance of dosage. Caution: When experimenting with osmotic stress, monitor cellular viability every 6 hours to avoid irreversible damage.

Light and Temperature: Subtle Yet Powerful Regulators

Light quality and temperature shifts act as subtle environmental triggers for sporulation in haploid algae and fungi. For example, *Physarum polycephalum*, a slime mold, sporulates under red light (660 nm) but remains vegetative under blue light (450 nm). In *Neurospora crassa*, a temperature drop from 25°C to 15°C induces spore formation within 72 hours. Takeaway: For optimal sporulation, mimic natural light-dark cycles and gradual temperature changes, avoiding abrupt shifts that could stress the cells.

Chemical Signals: The Role of Pheromones and Hormones

In some haploid organisms, chemical signals from neighboring cells or environmental sources trigger sporulation. For instance, mating pheromones in *Schizosaccharomyces pombe* induce haploid cells to form spores during sexual reproduction. In plants like ferns, the plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA) at concentrations of 50–100 μM promotes spore dormancy and germination. Comparative analysis: While pheromones act as short-range signals, hormones like ABA can influence sporulation across larger ecological scales, making them valuable tools for crop preservation and propagation.

PH and Oxidative Stress: Niche-Specific Triggers

Extreme pH levels and oxidative stress are niche-specific triggers for haploid sporulation. Acidic environments (pH 4.0–5.0) induce spore formation in *Penicillium* species, while oxidative stress from hydrogen peroxide (1–5 mM) triggers sporulation in *Cryptococcus neoformans*. Practical tip: When using oxidative stress, pre-treat cells with antioxidants like 1 mM ascorbic acid to enhance survival rates during sporulation.

By manipulating these environmental triggers, researchers and practitioners can control haploid sporulation for applications ranging from food preservation to biofuel production. Each trigger requires precise calibration to balance stress induction and cellular viability, ensuring successful spore formation.

Are Spore Servers Still Active? Exploring the Current Status

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, haploid cells cannot form spores by meiosis. Meiosis is a process that reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid, and haploid cells already have a single set of chromosomes. Spores are typically formed by haploid cells through mitosis, not meiosis.

Haploid cells use mitosis to form spores. Mitosis allows haploid cells to produce genetically identical daughter cells, which can develop into spores under favorable conditions.

Haploid cells do not undergo meiosis to form spores because meiosis is specifically for reducing the chromosome number from diploid to haploid. Since haploid cells already have a single set of chromosomes, meiosis would not serve a purpose in spore formation.

Yes, spores are typically formed by haploid cells in organisms like fungi, plants, and some protists. These haploid cells undergo mitosis to produce spores, which can later germinate into new individuals under suitable conditions.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)