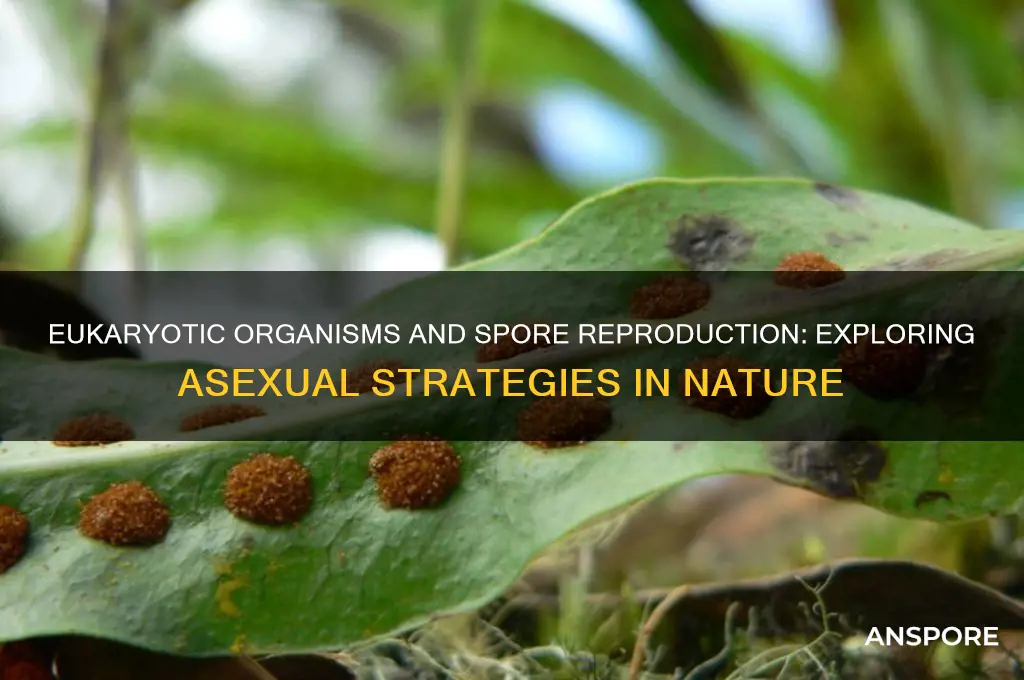

The kingdom Eukarya encompasses a vast array of organisms, including protists, fungi, plants, and animals, each with distinct reproductive strategies. Among these, spore reproduction is a notable method employed by certain eukaryotic organisms, particularly fungi and some plants. Spores are specialized cells capable of developing into new individuals under favorable conditions, allowing for efficient dispersal and survival in harsh environments. Fungi, for instance, produce spores as part of their life cycle, which can remain dormant until conditions are suitable for growth. Similarly, non-vascular plants like ferns and mosses rely on spores for reproduction, while vascular plants such as ferns and some seedless vascular plants also utilize this method. However, not all eukaryotic organisms reproduce via spores; animals and many other groups rely on sexual or asexual methods involving gametes or cell division. Thus, while spore reproduction is a significant strategy within Eukarya, it is not universal across the kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Kingdom | Eukarya |

| Reproduction via Spores | Yes, certain organisms within Eukarya can reproduce via spores. |

| Organisms Capable of Spore Reproduction | Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), some Protists (e.g., slime molds), and certain Plants (e.g., ferns, mosses). |

| Types of Spores | Asexual spores (e.g., conidia, zoospores) and sexual spores (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Function of Spores | Survival in harsh conditions, dispersal, and asexual/sexual reproduction. |

| Cellular Structure | Spores are typically haploid (single set of chromosomes) in plants and fungi, but can vary depending on the organism and life cycle stage. |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, resisting extreme temperatures, desiccation, and other adverse conditions. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions, developing into new individuals or structures (e.g., hyphae, gametophytes). |

| Life Cycle Integration | Spore reproduction is often part of complex life cycles, such as alternation of generations in plants and fungi. |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a key role in ecosystem dynamics, contributing to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and colonization of new habitats. |

| Examples | Fungal spores (e.g., Penicillium, Aspergillus), fern spores, and moss spores. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fungal spore reproduction mechanisms

Fungi, a diverse group within the Eukarya domain, have mastered the art of spore reproduction, a strategy that ensures their survival and proliferation in various environments. This mechanism is not just a means of reproduction but a sophisticated adaptation that allows fungi to disperse, colonize new habitats, and endure harsh conditions. The process begins with the formation of specialized structures, such as sporangia or asci, where spores are produced through either asexual or sexual means. Asexual spores, like conidia, are formed via mitosis and are common in molds, enabling rapid multiplication. Sexual spores, such as asci or basidiospores, result from meiosis and genetic recombination, promoting diversity and adaptability.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus*, a ubiquitous mold. When conditions are favorable, it produces conidia on stalk-like structures called conidiophores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air currents, allowing the fungus to colonize new substrates quickly. In contrast, during sexual reproduction, *Aspergillus* forms cleistothecia, structures that protect developing ascospores. This dual reproductive strategy highlights the fungus’s ability to thrive in both stable and changing environments. For practical purposes, understanding this mechanism is crucial in controlling fungal growth in food storage or medical settings, where spore dispersal can lead to contamination or infection.

From a comparative perspective, fungal spore reproduction stands out among eukaryotic organisms for its efficiency and versatility. Unlike plants, which rely on seeds for dispersal, or animals, which reproduce via gametes, fungi produce spores in vast quantities, often with specialized structures for ejection or wind dispersal. For instance, the mushroom’s gills are designed to release basidiospores into the air, ensuring wide distribution. This contrasts with the localized dispersal of plant seeds, which often depend on external agents like animals or water. Fungi’s ability to produce both asexual and sexual spores further enhances their survival, a feature not commonly found in other eukaryotic groups.

To harness or control fungal spore reproduction, specific conditions must be manipulated. Sporulation in fungi is triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, or temperature changes. For example, *Neurospora crassa*, a model fungus, initiates sexual spore formation under nitrogen-limited conditions. In industrial settings, controlling humidity and temperature can inhibit spore production in molds like *Penicillium*. For gardeners, ensuring proper air circulation and avoiding waterlogging can prevent fungal spore germination on plants. These practical tips underscore the importance of understanding spore mechanisms to manage fungal growth effectively.

In conclusion, fungal spore reproduction mechanisms are a testament to the adaptability and resilience of fungi within the Eukarya domain. By producing spores through asexual and sexual pathways, fungi ensure genetic diversity, rapid dispersal, and survival in adverse conditions. Whether in natural ecosystems or human-controlled environments, these mechanisms play a pivotal role in fungal proliferation. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can better manage fungal growth, from preserving food to treating infections, highlighting the practical significance of this unique reproductive strategy.

Are All Spores Diploid? Unraveling the Genetic Makeup of Spores

You may want to see also

Plant spore dispersal methods

Plants within the kingdom Eukarya employ a variety of ingenious methods to disperse their spores, ensuring the survival and propagation of their species. One of the most common and efficient techniques is wind dispersal. Spores are often lightweight and equipped with structures like wings or hairs, allowing them to be carried over vast distances by air currents. For instance, ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, which are so small and light that even a gentle breeze can transport them kilometers away. This method maximizes the chances of spores landing in new, potentially habitable environments, though it relies heavily on unpredictable wind patterns.

Another fascinating dispersal method is water dispersal, particularly in aquatic or semi-aquatic plants. Spores of species like the water fern *Salvinia* are buoyant and can float on water surfaces until they reach suitable substrates to germinate. This strategy is highly effective in wetland ecosystems, where water flow can carry spores to new locations with minimal energy expenditure from the plant. However, it is limited to environments with consistent water bodies, making it less versatile than wind dispersal.

Animal-mediated dispersal is a less common but equally intriguing method. Some plants produce spores with sticky or hook-like structures that attach to the fur or feathers of passing animals. For example, certain mosses and liverworts rely on this mechanism to transport their spores to new areas. While this method is more targeted than wind or water dispersal, it depends on the movement patterns of animals, which can be unpredictable. Additionally, the success rate is lower compared to more widespread dispersal techniques.

A more specialized approach is explosive spore release, seen in plants like the genus *Pilobolus*, a type of fungus-like organism. These plants use internal pressure to eject their spores with remarkable force, often targeting the undersides of grazing animals. The spores stick to the animal’s body and are later deposited in its feces, ensuring they land in nutrient-rich soil. This method is highly efficient but requires precise timing and energy investment from the plant.

Lastly, self-dispersal mechanisms are employed by some plants, such as the snapping movements of spore capsules in certain mosses. When conditions are dry, these capsules contract, propelling spores into the air. This method is energy-efficient and does not rely on external agents, but its range is limited compared to wind or animal dispersal. Each of these strategies highlights the adaptability of plants in ensuring their spores reach new habitats, showcasing the diversity of reproductive methods within the Eukarya kingdom.

Ordering Spores and PF Tek: Legal Risks and Consequences Explained

You may want to see also

Protozoan spore formation processes

Protozoans, single-celled eukaryotic organisms, exhibit diverse reproductive strategies, yet spore formation remains a less common but fascinating mechanism among them. Unlike fungi or plants, not all protozoans produce spores, but those that do employ unique processes tailored to their environments. For instance, *Sporozoa*, a subclass of protozoans, includes species like *Plasmodium* (the malaria parasite), which forms spores called oocysts within mosquito vectors. This process is critical for their life cycle, ensuring survival and transmission between hosts. Understanding these spore formation processes sheds light on protozoan resilience and adaptability.

Analyzing the spore formation in *Microsporidia*, another group of spore-forming protozoans, reveals a highly specialized mechanism. These organisms produce resistant spores with thick walls to withstand harsh conditions, such as desiccation or extreme temperatures. The spore contains a coiled polar tube, a structure that allows the infective sporoplasm to be injected into a new host cell upon germination. This process is not only efficient but also highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of protozoans in ensuring their propagation. Notably, *Microsporidia* spores can remain viable for years, making them formidable pathogens in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

From a practical standpoint, understanding protozoan spore formation is crucial for controlling diseases caused by these organisms. For example, *Cryptosporidium*, a waterborne protozoan, forms oocysts that are highly resistant to chlorine disinfection. This resistance poses significant challenges in water treatment plants, where standard methods may fail to eliminate the spores. Implementing advanced filtration techniques, such as ultrafiltration or UV disinfection, can effectively reduce oocyst contamination. Additionally, public health strategies should focus on educating communities about boiling water in areas with known outbreaks, as this simple step can inactivate the spores.

Comparatively, spore formation in protozoans differs significantly from that in fungi or plants, primarily due to the absence of complex multicellular structures. Protozoan spores are often smaller, more resilient, and designed for rapid dispersal and infection. For instance, while fungal spores rely on wind or water for dispersal, protozoan spores frequently exploit host vectors or direct contact. This distinction underscores the importance of studying protozoan spore formation independently, as their mechanisms are finely tuned to their unicellular lifestyle. Such insights are invaluable for both ecological research and disease management.

In conclusion, protozoan spore formation processes are a testament to the adaptability and survival strategies of these unicellular eukaryotes. From the oocysts of *Plasmodium* to the resilient spores of *Microsporidia*, each process is uniquely tailored to the organism’s life cycle and environment. By studying these mechanisms, we not only gain insights into protozoan biology but also develop targeted strategies to combat protozoan-borne diseases. Whether through advanced water treatment methods or public health interventions, understanding spore formation is key to mitigating the impact of these microscopic yet formidable organisms.

Can Your Vacuum Harbor Ringworm Spores? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Algal spore types and functions

Algae, a diverse group of eukaryotic organisms, employ various spore types as part of their reproductive strategies. These spores are not merely dormant structures but specialized cells with distinct functions, ensuring survival and dispersal in diverse environments. From freshwater ponds to marine ecosystems, algal spores play a critical role in maintaining species continuity and ecological balance. Understanding their types and functions provides insights into algal life cycles and their adaptability to changing conditions.

One prominent example is the zyspore, produced by certain green algae like *Chlamydomonas*. These spores form during sexual reproduction and are encased in a thick, resistant wall, enabling them to withstand harsh conditions such as desiccation or extreme temperatures. Zyspores remain dormant until environmental cues, such as increased moisture or favorable light, trigger germination. This mechanism ensures that algal populations can persist through unfavorable periods, a survival strategy akin to seed dormancy in plants.

In contrast, carpospores are characteristic of red algae (Rhodophyta) and are formed within specialized structures called carposporangia. These spores are part of a complex triphasic life cycle, where they develop into the diploid phase of the alga. Carpospores are released into the water, settling on substrates to grow into new individuals. Their function is not just reproductive but also ecological, as they contribute to the colonization of new habitats and the maintenance of genetic diversity within populations.

Another notable spore type is the hypnospore, found in certain blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) and some green algae. Hypnospores are akinetes—thick-walled, dormant cells that form in response to nutrient depletion or other stressors. Unlike other spores, hypnospores often remain attached to the parent organism, forming chains or clusters. This strategy minimizes dispersal risks while ensuring that the spores can quickly resume growth when conditions improve. For aquarists or researchers cultivating algae, recognizing hypnospore formation can indicate the need to adjust nutrient levels or environmental conditions.

Finally, zoospores represent a unique spore type in algae, particularly in groups like the brown algae (Phaeophyceae) and some green algae. These spores are motile, equipped with flagella that allow them to swim through water in search of suitable substrates. Zoospores are short-lived but highly efficient in dispersal, making them crucial for rapid colonization of new areas. Their function highlights the dynamic nature of algal reproduction, blending mobility with environmental responsiveness.

In practical terms, understanding algal spore types and functions has applications in aquaculture, biotechnology, and environmental management. For instance, cultivating algae for biofuel production requires optimizing spore germination rates, which can be achieved by mimicking natural triggers like light exposure or temperature shifts. Similarly, controlling spore dispersal in aquatic ecosystems can help manage algal blooms, which often disrupt water quality and biodiversity. By studying these spores, we gain not only theoretical knowledge but also tools to harness algae’s potential and mitigate their challenges.

Algae Spores Fusion: Understanding Diploids Formation in Algal Life Cycles

You may want to see also

Spore-based life cycles in eukaryotes

Eukaryotic organisms, from fungi to plants, employ spore-based life cycles as a survival strategy, ensuring resilience across generations. Spores are lightweight, durable cells capable of withstanding harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and nutrient scarcity. For instance, ferns release spores that can lie dormant for years, germinating only when environmental conditions become favorable. This adaptability highlights the evolutionary advantage of spore reproduction, allowing species to persist in unpredictable ecosystems.

Consider the life cycle of a fungus like *Aspergillus*, a common mold. It alternates between vegetative growth and spore production, a process known as alternation of generations. During the asexual phase, it forms conidia—single-celled spores dispersed by air currents. These spores can travel vast distances, colonizing new substrates upon landing. The sexual phase involves the fusion of gametes, resulting in the formation of thicker-walled spores called ascospores, which offer enhanced protection against environmental stressors. This dual reproductive strategy ensures both rapid proliferation and long-term survival.

Plants like mosses and liverworts also rely on spores, showcasing a simpler life cycle compared to vascular plants. In these bryophytes, the gametophyte generation dominates, producing spores via meiosis. These spores develop into thread-like protonema, which eventually grow into mature gametophytes. Notably, this cycle bypasses the seed stage, making it highly dependent on moisture for spore dispersal and germination. For gardeners cultivating moss, maintaining consistent humidity is crucial to mimic the natural conditions required for spore viability.

A comparative analysis reveals that spore-based life cycles in eukaryotes share common themes but diverge in complexity. Fungi and plants both use spores for dispersal and survival, yet fungi often exhibit more intricate reproductive phases, including both asexual and sexual spore types. In contrast, plant spores are typically unicellular and haploid, focusing on dispersal rather than genetic diversity. This variation underscores the versatility of spore reproduction across eukaryotic domains.

To harness the potential of spore-based life cycles, researchers and enthusiasts alike can experiment with spore cultivation. For example, growing ferns from spores requires a sterile medium, such as a mixture of peat moss and perlite, kept at a temperature of 20–25°C. Spores should be lightly sprinkled on the surface and covered with a transparent lid to maintain humidity. Germination typically occurs within 2–4 weeks, with protonema appearing first. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding of eukaryotic life cycles but also fosters appreciation for the ingenuity of spore-based reproduction.

Can Dehydrated Morel Spores Still Grow Mushrooms? Viability Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all eukaryotic organisms reproduce with spores. While some groups like fungi, plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and certain protists use spores for reproduction, many others, such as animals and most algae, do not.

Spore reproduction in Eukarya serves as a survival and dispersal mechanism. Spores are highly resistant structures that can withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures. They also allow organisms to spread to new habitats over long distances.

Spores are typically single-celled and lack stored food reserves, relying on favorable conditions to germinate. Seeds, on the other hand, are multicellular structures with stored nutrients (e.g., endosperm) that support the developing embryo until it can photosynthesize or establish itself.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)