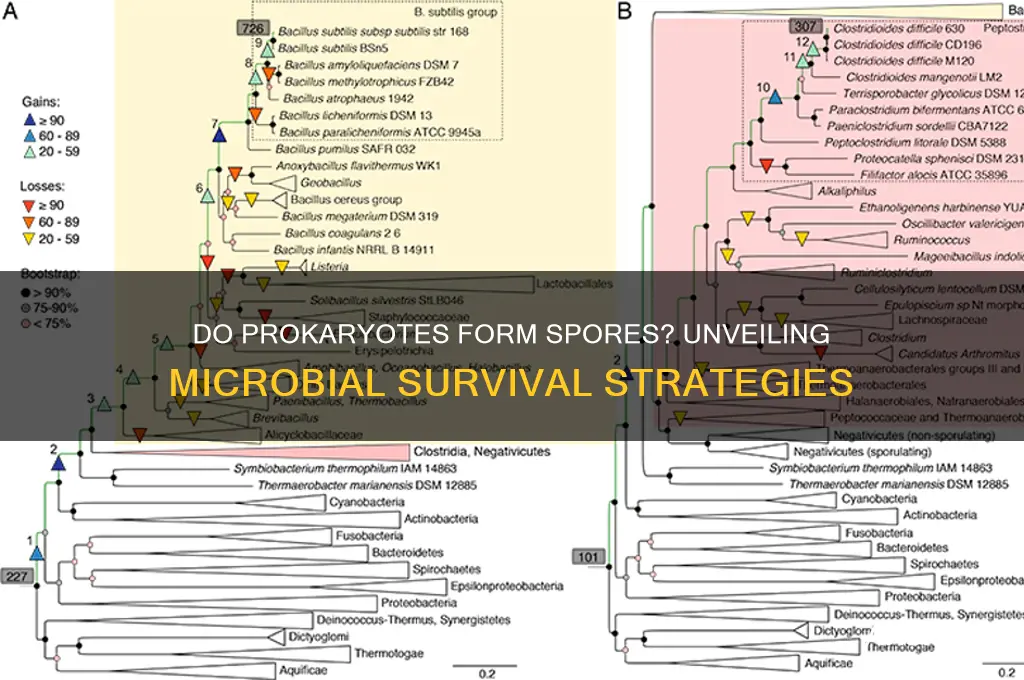

Prokaryotes, which include bacteria and archaea, are single-celled organisms that lack a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. While not all prokaryotes form spores, certain bacterial species, such as those in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are capable of producing highly resistant endospores as a survival mechanism. These spores allow the bacteria to withstand extreme environmental conditions, including heat, desiccation, and radiation, by entering a dormant state. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are metabolically inactive and can remain viable for extended periods, sometimes even centuries, until favorable conditions return. This ability to form spores is a unique and adaptive feature among prokaryotes, distinguishing them from other microorganisms and contributing to their widespread distribution and persistence in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Prokaryotes Contain Spores? | Yes |

| Types of Prokaryotes Forming Spores | Primarily bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) |

| Purpose of Spores | Survival in harsh conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals) |

| Structure of Spores | Highly resistant, dormant cells with thick protective coats |

| Metabolic Activity in Spores | Minimal to none (dormant state) |

| Germination Process | Spores revert to active bacterial cells under favorable conditions |

| Examples of Spore-Forming Bacteria | Bacillus anthracis, Clostridium botulinum, Sporosarcina ureae |

| Location of Spores in Prokaryotes | Typically formed within the bacterial cell (endospores) |

| Resistance Capabilities | Heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemical agents |

| Significance in Environment | Long-term survival in adverse environments |

| Medical and Industrial Relevance | Pathogenic concerns (e.g., anthrax) and applications in biotechnology |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process in Prokaryotes: How and why prokaryotes form spores under stress conditions

- Types of Prokaryotic Spores: Endospores, cysts, and other spore forms in bacteria and archaea

- Survival Mechanisms: Role of spores in prokaryotic survival in harsh environments

- Germination of Spores: Conditions and triggers for spore activation in prokaryotes

- Examples of Spore-Forming Prokaryotes: Species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* that produce spores

Sporulation Process in Prokaryotes: How and why prokaryotes form spores under stress conditions

Prokaryotes, particularly certain bacteria, employ sporulation as a survival strategy when faced with adverse environmental conditions. This process involves the formation of highly resistant endospores, which can endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium botulinum* are well-known spore-forming bacteria. The sporulation process is a complex, multi-step transformation that begins with the depletion of essential nutrients or other stressors, triggering a genetic cascade that ultimately results in the creation of a spore within the bacterial cell.

Steps in Sporulation: The process starts with an asymmetric cell division, producing a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a double membrane structure. Next, the forespore synthesizes a thick, protective coat composed of proteins and peptidoglycan, while the mother cell degrades its own DNA and provides nutrients to the developing spore. Finally, the mature spore is released upon lysis of the mother cell. This entire process can take several hours, depending on the bacterial species and environmental conditions.

Why Sporulation Occurs: Sporulation is a last-resort mechanism for prokaryotes to ensure survival in harsh environments. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can remain dormant for years, even decades, until conditions improve. For example, soil-dwelling bacteria like *Bacillus* species form spores during nutrient scarcity or exposure to UV radiation. Similarly, *Clostridium* species sporulate in oxygen-rich environments, where their anaerobic metabolism is compromised. This adaptability highlights the evolutionary advantage of sporulation, allowing bacteria to persist in diverse and challenging ecosystems.

Practical Implications: Understanding sporulation is crucial in fields like food safety and medicine. Spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, for instance, can survive standard cooking temperatures and cause botulism if ingested. To eliminate such risks, food preservation methods like pressure cooking (121°C for 3 minutes) or irradiation are employed to destroy spores. In contrast, sporulation is harnessed in biotechnology for the production of enzymes and other biomolecules, as spores can be easily stored and reactivated. For researchers, studying sporulation provides insights into bacterial resilience and potential targets for antimicrobial therapies.

Cautions and Considerations: While spores are remarkably resilient, they are not invincible. Prolonged exposure to extreme conditions, such as high doses of gamma radiation (>10 kGy) or strong oxidizing agents, can destroy them. Additionally, spore germination is a vulnerable phase, as the emerging vegetative cell is susceptible to antibiotics and environmental stressors. Thus, controlling sporulation and germination is key to managing bacterial populations in both beneficial and harmful contexts. By studying these processes, scientists can develop more effective strategies for combating pathogenic bacteria and optimizing biotechnological applications.

Black Mold Spores: Potential Link to Elevated White Blood Cell Counts

You may want to see also

Types of Prokaryotic Spores: Endospores, cysts, and other spore forms in bacteria and archaea

Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, have evolved diverse strategies to survive harsh environmental conditions, and one of the most remarkable is the formation of spores. These dormant, highly resistant structures allow prokaryotes to endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemical stressors. Among the various types of prokaryotic spores, endospores, cysts, and other specialized forms stand out for their unique characteristics and survival mechanisms.

Endospores, primarily produced by certain Gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are the most resilient spore type. Formed within the bacterial cell through a process called sporulation, endospores consist of a core containing DNA and essential enzymes, surrounded by multiple protective layers. These layers include the spore coat, cortex, and sometimes an exosporium, which collectively provide resistance to heat, UV radiation, and chemicals. For example, *Bacillus anthracis* endospores can survive in soil for decades, making them a significant concern in bioterrorism. To inactivate endospores, extreme measures such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes are required, underscoring their robustness.

Cysts, in contrast, are less complex than endospores and are typically formed by protozoa and some bacteria, such as *Azotobacter*. These structures are essentially dormant cells encased in a protective wall, allowing them to withstand unfavorable conditions like nutrient depletion or desiccation. Unlike endospores, cysts retain their cellular structure and can revert to active growth when conditions improve. For instance, *Azotobacter* cysts are crucial for nitrogen fixation in soil, as they can survive until nutrients become available. While cysts are less resistant than endospores, they serve as an effective survival mechanism in fluctuating environments.

Beyond endospores and cysts, other spore-like forms exist in prokaryotes, particularly in archaea. Archaeal spores, though less studied, exhibit unique adaptations to extreme environments. For example, *Halobacterium* species form structures resembling spores under high-salt conditions, enabling survival in hypersaline environments. Similarly, myxospores in myxobacteria are formed during fruiting body development, providing resistance to environmental stresses. These diverse spore forms highlight the evolutionary ingenuity of prokaryotes in adapting to challenging habitats.

Understanding the types and functions of prokaryotic spores has practical implications, from food preservation to medical sterilization. For instance, knowing that endospores require high temperatures for inactivation informs sterilization protocols in laboratories and hospitals. Conversely, cysts’ ability to survive in soil influences agricultural practices, particularly in nutrient-poor environments. By studying these spore forms, scientists can develop targeted strategies to control harmful bacteria or harness beneficial ones, emphasizing the importance of spore biology in both applied and fundamental research.

Are Psilocybin Spores Illegal? Understanding the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Role of spores in prokaryotic survival in harsh environments

Prokaryotes, particularly bacteria, have evolved remarkable strategies to endure extreme conditions, and one of their most fascinating survival mechanisms is the formation of spores. These highly resistant structures enable prokaryotes to withstand environmental stresses that would otherwise be lethal, such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, and exposure to radiation or toxic chemicals. Spores are not just a passive defense; they are a sophisticated adaptation that ensures the long-term survival of the species. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium botulinum* are well-known spore-forming bacteria that can persist in soil, water, and even food products for years, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate.

The process of spore formation, or sporulation, is a complex, energy-intensive transformation that involves the differentiation of a bacterial cell into a spore and a mother cell. The mother cell eventually lyses, releasing the spore, which is encased in multiple protective layers, including a thick peptidoglycan cortex and a proteinaceous coat. These layers provide resistance to heat, UV radiation, and enzymes, making spores nearly indestructible. For example, bacterial spores can survive boiling water for extended periods, a trait exploited in food preservation techniques like canning, where temperatures of 121°C (250°F) for 15–20 minutes are required to ensure their destruction.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore survival mechanisms is critical in industries such as healthcare, food safety, and environmental management. Spores of pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* can persist on hospital surfaces, leading to healthcare-associated infections, while *Bacillus anthracis* spores are notorious for their role in bioterrorism. To combat these threats, effective disinfection protocols must account for spore resistance. For instance, hydrogen peroxide vaporization or chlorine-based disinfectants at concentrations of 5,000–10,000 ppm are recommended for spore decontamination in clinical settings. Similarly, in food processing, methods like autoclaving or the use of spore-specific bacteriophages are employed to eliminate spores from products.

Comparatively, while eukaryotic organisms like fungi also produce spores, prokaryotic spores are uniquely adapted to their microscopic scale and metabolic simplicity. Unlike fungal spores, which often serve as dispersal units, prokaryotic spores are primarily survival structures. This distinction highlights the evolutionary pressures faced by prokaryotes, which lack the cellular complexity of eukaryotes and must rely on such extreme measures to endure. For example, spores of *Deinococcus radiodurans*, a bacterium known for its radiation resistance, can repair DNA damage from doses as high as 15,000 gray (Gy), a level that would be fatal to most organisms.

In conclusion, the role of spores in prokaryotic survival is a testament to the ingenuity of microbial life. These structures are not merely a passive shield but a dynamic response to environmental challenges, ensuring the persistence of prokaryotes in even the harshest conditions. By studying spore formation and resistance, scientists can develop more effective strategies for controlling pathogens, preserving food, and even exploring the limits of life in extreme environments, such as those found on other planets. The spore, in its simplicity, encapsulates the resilience and adaptability that define prokaryotic life.

Spores vs. Seeds: Which is More Effective for Plant Propagation?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination of Spores: Conditions and triggers for spore activation in prokaryotes

Prokaryotes, particularly bacteria, form spores as a survival strategy in harsh conditions. These dormant structures can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, but their true marvel lies in germination—the process of returning to an active, vegetative state. Understanding the conditions and triggers for spore activation is crucial for fields ranging from food safety to biotechnology. Unlike vegetative cells, spores require specific environmental cues to resume growth, ensuring they only activate when conditions are favorable.

Conditions for Germination: A Precise Recipe

Germination is not spontaneous; it demands a precise combination of factors. First, water availability is critical. Spores must absorb sufficient water to rehydrate their cellular machinery, typically requiring a water activity (aw) of 0.9 or higher. Nutrient availability is equally important, with specific amino acids, sugars, or salts acting as potent germinants. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores often require L-valine or a combination of glucose and fructose to initiate germination. Temperature also plays a role, with most bacterial spores germinating optimally between 25°C and 40°C. Deviations from these conditions can delay or inhibit activation, highlighting the spore’s adaptability to its environment.

Triggers: The Molecular Wake-Up Call

Germination begins with the binding of germinants to specific receptors on the spore’s surface. In *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, these receptors are part of the germinant-receptor complex, which triggers the release of dipicolinic acid (DPA) and calcium ions from the spore’s core. This release is a critical step, as DPA is a key factor in maintaining spore dormancy. Once expelled, the spore’s core hydrates, and enzymes like hydrolytic enzymes become active, degrading the spore’s protective coat. This cascade of events is irreversible, committing the spore to returning to its vegetative form.

Practical Implications: Controlling Spore Activation

In food preservation, preventing spore germination is essential to avoid spoilage or foodborne illness. Techniques like heat treatment (e.g., pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds) or chemical preservatives (e.g., nitrites in cured meats) target spore activation. Conversely, in biotechnology, controlled germination is used to produce enzymes or metabolites. For instance, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores are germinated under specific conditions to produce insecticidal proteins. Understanding germination triggers allows for precise manipulation of spore behavior, whether to inhibit or promote their activation.

Comparative Perspective: Eukaryotic vs. Prokaryotic Spores

While prokaryotic spores share some germination principles with eukaryotic spores (e.g., fungi), the mechanisms differ significantly. Eukaryotic spores often require light, oxygen, or specific pH levels for activation, whereas prokaryotic spores rely on nutrient availability and hydration. This distinction underscores the evolutionary divergence in spore strategies. For example, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* germinate in response to light, a trigger irrelevant to prokaryotic spores. Such comparisons highlight the unique adaptations of prokaryotes to their microbial world.

Takeaway: A Balanced Approach to Spore Management

Germination of prokaryotic spores is a finely tuned process, requiring specific environmental conditions and molecular triggers. Whether in food safety, medicine, or biotechnology, controlling spore activation demands a nuanced understanding of these factors. By manipulating water availability, nutrients, and temperature, we can either prevent unwanted germination or harness its potential for beneficial applications. This delicate balance between dormancy and activation is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of prokaryotic life.

Are Laccaria Spores White? Unveiling the Truth About Their Color

You may want to see also

Examples of Spore-Forming Prokaryotes: Species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* that produce spores

Prokaryotes, particularly certain bacterial species, have evolved a remarkable survival strategy: spore formation. Among these, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* stand out as prime examples of spore-forming prokaryotes. These spores are highly resistant structures that allow the bacteria to endure extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, can remain dormant in soil for decades as a spore, only to germinate and cause disease when conditions become favorable. Similarly, *Clostridium botulinum*, responsible for botulism, produces spores that can survive boiling temperatures, making it a significant concern in food preservation.

Understanding the spore-forming capabilities of these bacteria is crucial for both medical and industrial applications. *Bacillus subtilis*, a non-pathogenic species, is widely studied for its ability to produce spores that can withstand harsh environments. This has led to its use in biotechnology, such as in the production of enzymes and biofertilizers. In contrast, *Clostridium difficile*, a major cause of hospital-acquired infections, forms spores that are resistant to routine cleaning agents, necessitating specialized disinfection protocols. For healthcare settings, this means using sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm) to effectively eliminate *C. difficile* spores from surfaces.

The process of spore formation, or sporulation, is a complex and energy-intensive mechanism. In *Bacillus* species, it involves the differentiation of a vegetative cell into a spore through a series of morphological and biochemical changes. The resulting spore is encased in a protective coat and cortex, making it highly resilient. For example, *Bacillus cereus*, a common foodborne pathogen, can form spores that survive cooking temperatures, leading to outbreaks if contaminated food is not stored properly. Practical tips for preventing such outbreaks include reheating food to at least 75°C (167°F) and refrigerating leftovers promptly.

Comparatively, *Clostridium* species also undergo sporulation, but their spores often have additional layers, such as an exosporium, which further enhances their durability. *Clostridium perfringens*, another foodborne pathogen, produces spores that can germinate rapidly in the human gut, causing illness. This highlights the importance of proper food handling, particularly in large-scale cooking, where temperature abuse (e.g., holding food between 15°C and 60°C) can allow spores to germinate and multiply. To mitigate this, follow the "2-hour rule": discard perishable food left at room temperature for more than 2 hours.

In conclusion, spore-forming prokaryotes like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* exemplify the adaptability of bacteria in harsh environments. Their spores are not only a survival mechanism but also a challenge in medical and industrial settings. By understanding their biology and implementing targeted strategies, such as using sporicidal agents and proper food handling practices, we can effectively manage the risks associated with these resilient organisms. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or kitchen, awareness of spore-forming bacteria is key to preventing their detrimental effects.

Can Moldy Food Spores Trigger Respiratory Infections? Uncover the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, certain prokaryotes, particularly bacteria, can form spores as a survival mechanism in harsh environmental conditions.

Primarily, spore-forming prokaryotes include bacteria from the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, which are well-known for their ability to produce endospores.

Spore formation allows prokaryotes to survive extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, radiation, and lack of nutrients by entering a dormant, highly resistant state.

No, only specific groups of prokaryotes, such as certain bacterial species, have the ability to form spores. Most prokaryotes do not possess this capability.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)