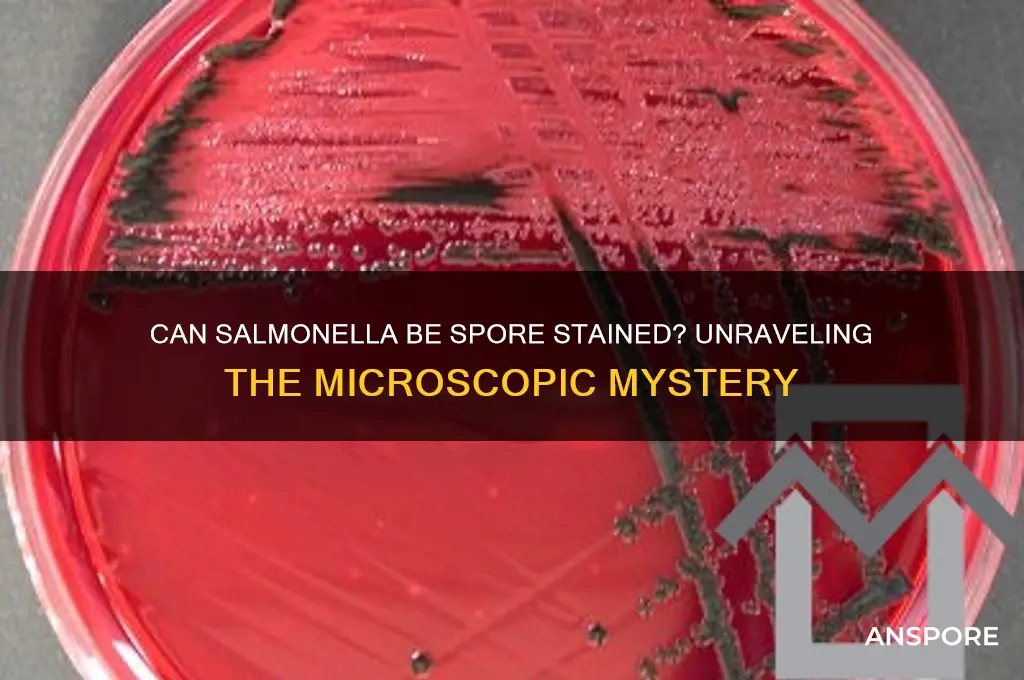

Salmonella, a gram-negative bacterium commonly associated with foodborne illnesses, is known for its rod-shaped morphology and inability to form spores. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, Salmonella lacks the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation. As a result, traditional spore staining techniques, which rely on the presence of endospores, are not applicable to Salmonella. Instead, identification of Salmonella typically involves gram staining, biochemical tests, and molecular methods like PCR. Understanding the non-spore-forming nature of Salmonella is crucial for accurate laboratory diagnosis and appropriate public health interventions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Salmonella be spore stained? | No, Salmonella cannot be spore stained. |

| Reason | Salmonella is a non-spore-forming bacterium (facultative anaerobe). |

| Spore staining applicability | Spore staining is used for detecting endospores in spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Salmonella classification | Gram-negative, rod-shaped, motile bacterium. |

| Endospore production | Salmonella does not produce endospores. |

| Relevant staining methods | Gram staining, differential staining (e.g., MacConkey agar), or immunological tests are used for Salmonella identification. |

| Clinical significance | Causes salmonellosis, a foodborne illness characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms. |

| Laboratory detection | Cultured on selective media (e.g., Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate agar) and confirmed via biochemical tests or PCR. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Stain Technique: Gram staining vs. spore-specific methods for Salmonella detection

- Salmonella Characteristics: Non-spore-forming nature of Salmonella bacteria

- Spore Formation: Comparison with spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus

- Laboratory Challenges: Why Salmonella cannot be spore stained

- Alternative Tests: Methods to identify Salmonella without spore staining

Spore Stain Technique: Gram staining vs. spore-specific methods for Salmonella detection

Salmonella, a notorious foodborne pathogen, lacks the ability to form spores, a critical distinction from spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. This fundamental difference dictates the choice of staining techniques for accurate detection. While Gram staining is a cornerstone of bacterial identification, its utility for Salmonella is limited to differentiating it from Gram-negative bacteria, offering no insight into spore presence. Spore-specific staining methods, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, rely on spores' resistance to decolorization and their ability to retain specific stains, characteristics Salmonella does not possess.

The Gram Stain: A Limited Tool for Salmonella

Gram staining, a differential staining technique, categorizes bacteria based on cell wall composition. Salmonella, being Gram-negative, will appear pink or red under the microscope after staining. However, this result merely confirms its Gram-negative nature, providing no information about spore formation. Gram staining is invaluable for initial bacterial classification but falls short when distinguishing Salmonella from other non-spore-forming Gram-negative pathogens.

Procedure: Heat-fix a smear of the bacterial culture on a slide, apply crystal violet, followed by Gram's iodine, decolorize with alcohol, and counterstain with safranin.

Spore Staining: A Misdirected Approach for Salmonella

Spore staining techniques are specifically designed to visualize endospores, the highly resistant dormant forms produced by certain bacteria. These methods exploit the spores' impermeability to water and dyes, allowing them to retain specific stains even after harsh decolorization. Since Salmonella lacks spores, these techniques will yield negative results, with all cells appearing uniformly stained by the counterstain.

Example: The Schaeffer-Fulton method uses malachite green as the primary stain, requiring heat to drive the dye into the spores. After decolorization with water, the spores retain the green color, while vegetative cells are counterstained red with safranin.

Implications for Salmonella Detection

The inability to spore stain Salmonella highlights the importance of selecting appropriate diagnostic techniques. Relying solely on Gram staining can lead to misidentification if other Gram-negative pathogens are present. For accurate Salmonella detection, culture-based methods on selective media, biochemical tests, and molecular techniques like PCR are far more reliable.

Practical Tip: When dealing with food samples, pre-enrichment in selective broths like Tetrathionate or Rappaport Vassiliadis can enhance Salmonella recovery before further testing.

While spore staining is a powerful tool for identifying spore-forming bacteria, it is irrelevant for Salmonella detection. Understanding the limitations of staining techniques and employing appropriate diagnostic methods is crucial for accurate identification and effective control of this significant foodborne pathogen.

Ethanol's Power: Can 7% Concentration Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Salmonella Characteristics: Non-spore-forming nature of Salmonella bacteria

Salmonella, a notorious pathogen responsible for foodborne illnesses, lacks the ability to form spores, a characteristic that sets it apart from other bacteria like Clostridium botulinum. This non-spore-forming nature is a critical aspect of its biology, influencing both its survival strategies and detection methods. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can withstand extreme conditions by entering a dormant, highly resistant state, Salmonella relies on active replication and immediate environmental resources for survival. This distinction is fundamental when considering techniques like spore staining, which are ineffective for identifying Salmonella due to its lack of spores.

From a laboratory perspective, the non-spore-forming nature of Salmonella necessitates specific diagnostic approaches. Spore staining, typically performed using methods like the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner techniques, targets the heat-resistant, thick-walled spores of certain bacteria. Since Salmonella does not produce spores, these staining methods yield negative results, making them unsuitable for its detection. Instead, laboratories rely on alternative techniques such as selective agar plating (e.g., MacConkey or XLD agar), biochemical tests, and molecular methods like PCR to identify Salmonella. Understanding this limitation of spore staining is crucial for accurate diagnosis and prevention of salmonellosis.

The absence of spore formation in Salmonella also has significant implications for its control in food and environmental settings. Without the ability to form spores, Salmonella is more susceptible to common disinfection methods, such as heat treatment (e.g., cooking at 65°C for 10 minutes) and sanitizing agents (e.g., chlorine-based solutions). However, its survival in dry environments or on surfaces can still pose risks, particularly in food processing facilities. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can persist for years in a dormant state, Salmonella’s viability decreases rapidly under adverse conditions, though it can still survive for weeks in favorable environments like moist, nutrient-rich materials.

For practical purposes, this characteristic of Salmonella informs food safety protocols. For instance, proper cooking and storage practices are essential to eliminate Salmonella, as it cannot revert to a spore-like state to evade destruction. Consumers and food handlers should focus on preventing cross-contamination, maintaining hygiene, and ensuring thorough cooking to temperatures that kill the bacteria. In contrast, spore-forming pathogens require more stringent measures, such as sterilization or prolonged heating, highlighting the importance of tailoring control strategies to the specific biology of the pathogen in question.

In summary, the non-spore-forming nature of Salmonella is a defining feature that shapes its detection, survival, and control. While this characteristic renders spore staining ineffective for its identification, it also makes Salmonella more vulnerable to standard disinfection methods compared to spore-forming bacteria. By understanding this unique aspect of Salmonella’s biology, laboratories, food safety professionals, and individuals can implement targeted measures to mitigate the risks associated with this pathogen, ultimately reducing the incidence of salmonellosis.

Exploring Sporangium: Are Spores Present Inside This Fungal Structure?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation: Comparison with spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus

Salmonella, a notorious foodborne pathogen, lacks the ability to form spores, a survival mechanism mastered by bacteria like Bacillus. This fundamental difference in physiology has significant implications for their detection, treatment, and control. While Bacillus species can endure extreme conditions by forming highly resistant spores, Salmonella relies on other strategies, such as biofilm formation and stress response mechanisms, to survive harsh environments. This distinction is crucial when considering staining techniques, as spore-specific stains like the Schaeffer-Fulton method are ineffective for Salmonella, necessitating alternative approaches like Gram staining or immunological assays for accurate identification.

Understanding spore formation in Bacillus provides a stark contrast to Salmonella's survival tactics. Bacillus spores are characterized by their multilayered structure, including a thick protein coat and a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid, which confers resistance to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This resilience allows Bacillus spores to persist in soil, water, and food for years, posing challenges in food safety and healthcare settings. In contrast, Salmonella's vegetative cells are more susceptible to environmental stressors, making them easier to eliminate through standard sanitation practices like pasteurization or cooking. However, their ability to multiply rapidly in favorable conditions underscores the importance of timely detection and intervention.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in Salmonella simplifies certain aspects of its control but complicates others. For instance, while Salmonella does not require the extreme measures needed to eradicate Bacillus spores, its widespread presence in animal reservoirs and its ability to contaminate diverse food products demand rigorous hygiene protocols. Laboratories must employ specific staining and culturing techniques, such as selective media like XLD agar, to isolate Salmonella effectively. Additionally, molecular methods like PCR have become invaluable for rapid and accurate detection, particularly in outbreak investigations where time is critical.

A comparative analysis of spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus and non-spore-forming pathogens like Salmonella highlights the evolutionary trade-offs in bacterial survival strategies. While spore formation ensures long-term persistence, it comes at the cost of metabolic dormancy and reduced adaptability. Salmonella, on the other hand, prioritizes rapid replication and host colonization, leveraging its ability to exploit nutrient-rich environments. This comparison underscores the need for tailored approaches in microbiology, whether in diagnostic testing, food safety measures, or therapeutic interventions. By recognizing these differences, scientists and practitioners can devise more effective strategies to combat these distinct yet equally significant pathogens.

Save Spore Creatures: Modding Tips for Preservation and Gameplay

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Laboratory Challenges: Why Salmonella cannot be spore stained

Salmonella, a notorious foodborne pathogen, lacks the ability to form spores, a critical factor that immediately disqualifies it from spore staining procedures. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, Salmonella exists solely in a vegetative state. Spore staining techniques, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, rely on the presence of endospores—highly resistant structures that can withstand extreme conditions. Since Salmonella lacks these structures, applying spore stains would yield no visible results, rendering the process futile.

From a laboratory perspective, the absence of spores in Salmonella simplifies identification but complicates certain diagnostic approaches. Spore staining is a specialized technique designed to differentiate between spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria. When a sample is suspected to contain spore-forming pathogens, this method is invaluable. However, for Salmonella, standard biochemical tests, serotyping, or molecular methods like PCR are more appropriate. Attempting spore staining on Salmonella not only wastes resources but also risks misinterpretation of results, as the absence of spores might falsely suggest contamination or procedural errors.

A comparative analysis highlights the stark contrast between Salmonella and spore-forming bacteria. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores can survive decades in soil, while Salmonella’s vegetative cells are relatively fragile, perishing under harsh conditions like high heat or desiccation. This biological difference underscores why Salmonella cannot be spore stained—it simply lacks the target structure. Laboratories must prioritize tests that align with the organism’s characteristics, such as culturing on selective media like XLD agar or using antibody-based assays for rapid detection.

Practically, understanding this limitation saves time and resources in clinical and food safety settings. For example, in a foodborne illness outbreak investigation, focusing on Salmonella’s motility, biochemical reactions, or antigenic markers is far more effective than attempting spore staining. Additionally, educating laboratory personnel about the biological distinctions between bacteria ensures accurate testing and reporting. While spore staining remains a cornerstone for certain pathogens, it is irrelevant for Salmonella, emphasizing the need for tailored diagnostic strategies.

Fungi Propagation: Understanding the Role of Spores in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Alternative Tests: Methods to identify Salmonella without spore staining

Salmonella, a leading cause of foodborne illness, cannot be identified through spore staining because it is a non-spore-forming bacterium. This limitation necessitates the use of alternative methods for accurate detection. One widely adopted approach is the culture-based method, which involves enriching the sample in selective media such as selenite broth or Rappaport-Vassiliadis (RV) broth. These media suppress the growth of competing microorganisms while promoting the proliferation of Salmonella. After enrichment, the sample is streaked onto differential plates like xylose-lysine-deoxycholate (XLD) agar or Hektoen enteric (HE) agar. On XLD agar, Salmonella colonies appear as black-centered with a reddish hue due to hydrogen sulfide production, providing a visual cue for identification.

For faster results, molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have become indispensable. PCR amplifies specific DNA sequences unique to Salmonella, allowing for detection within hours rather than days. Real-time PCR, or quantitative PCR (qPCR), further enhances this method by providing quantitative data on bacterial load, which is crucial for risk assessment in food safety. Multiplex PCR assays can simultaneously detect multiple serovars or virulence genes, increasing efficiency and specificity. These methods require minimal sample preparation and are highly sensitive, making them ideal for high-throughput testing in clinical and industrial settings.

Another alternative is the use of immunological assays, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or lateral flow devices. These tests rely on antibodies that bind specifically to Salmonella antigens, producing a detectable signal. ELISA, for instance, can be performed in microplate format, with results available within 2–4 hours. Lateral flow devices, often referred to as rapid tests, provide results in as little as 10–15 minutes, making them suitable for on-site testing. However, their sensitivity may be lower compared to PCR or culture methods, and confirmatory testing is often recommended for critical samples.

In resource-limited settings, biochemical tests remain a practical option. The triple sugar iron (TSI) agar test, for example, differentiates Salmonella based on its ability to ferment sugars and produce hydrogen sulfide. A slant with a yellow butt and a black center indicates a positive result. Similarly, the lysine iron agar (LIA) test and the urea test can be used to confirm the presence of Salmonella by assessing specific metabolic activities. While these methods are less rapid than molecular or immunological assays, they are cost-effective and do not require specialized equipment, making them accessible for basic diagnostic laboratories.

Lastly, chromogenic media offers a user-friendly alternative by incorporating color-producing substrates that react with Salmonella enzymes. Media such as CHROMagar Salmonella or Brilliance Salmonella Agar produce distinctively colored colonies, simplifying identification without the need for further testing. This method combines the reliability of culture-based techniques with the convenience of visual interpretation, making it a popular choice in routine diagnostics. However, it is essential to follow manufacturer instructions carefully, as incubation conditions (e.g., temperature, duration) can significantly impact results.

In summary, while Salmonella cannot be identified through spore staining, a variety of alternative methods—ranging from culture-based and molecular techniques to immunological and biochemical assays—provide reliable and efficient means of detection. The choice of method depends on factors such as turnaround time, cost, and available resources, ensuring flexibility in addressing diverse testing needs.

Can Coffee Kill Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind This Claim

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Salmonella cannot be spore stained because it is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

Salmonella does not produce spores, so there are no endospores to visualize or stain in the process.

Gram staining is commonly used for Salmonella, as it is a Gram-negative bacterium.

No, Salmonella is identified through other methods like biochemical tests, serotyping, and molecular techniques, not spore staining.

No, Salmonella belongs to the genus *Salmonella*, which does not include spore-forming species. Spore staining is used for bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*.