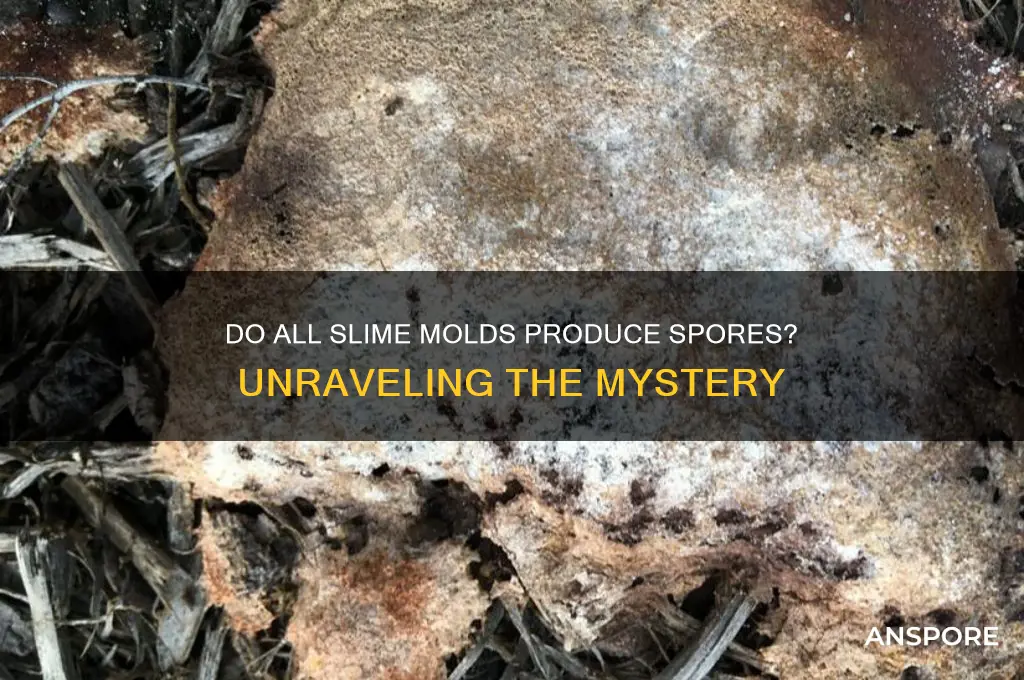

Slime molds, a diverse group of organisms often mistaken for fungi, exhibit a fascinating range of life cycles and reproductive strategies. While many slime molds are known to produce spores as a means of dispersal and survival, not all species follow this pattern. Some slime molds, particularly those in the plasmodial stage, can reproduce asexually through fragmentation, where parts of the organism break off and develop into new individuals. Additionally, certain species rely on other mechanisms, such as the release of motile cells or the formation of resistant structures like sclerotia. Therefore, while spore production is a common trait among slime molds, it is not universal, highlighting the complexity and diversity of these intriguing organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do all slime molds have spores? | No, not all slime molds produce spores. |

| Types of Slime Molds | Cellular Slime Molds (e.g., Dictyostelium) and Acellular Slime Molds (e.g., Physarum). |

| Spores in Cellular Slime Molds | Yes, they form spores during their life cycle. |

| Spores in Acellular Slime Molds | No, they do not produce spores; instead, they reproduce via fragmentation or spores-like structures in some cases. |

| Reproductive Structures | Sporangia (in cellular slime molds), plasmodiocarp (in some acellular slime molds). |

| Life Cycle | Alternation between vegetative (amoeboid or plasmodial) and reproductive (spore-forming) stages, but not all stages are present in all species. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores (in spore-producing species) are dispersed by wind, water, or animals. |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers, breaking down organic matter in ecosystems. |

| Taxonomic Classification | Formerly classified as fungi, now grouped in the kingdom Protista or Amoebozoa. |

| Examples of Spore-Producing Species | Dictyostelium discoideum, Stemonitis spp. |

| Examples of Non-Spore-Producing Species | Physarum polycephalum, Fuligo septica. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporangia Formation in Slime Molds

Slime molds, despite their name, are not molds but rather unique organisms that exhibit both fungal-like and animal-like characteristics. Among their fascinating traits is the formation of sporangia, a critical process in their life cycle. Sporangia are structures that produce and contain spores, which serve as the primary means of dispersal and survival for slime molds. However, not all slime molds follow the same path to sporangia formation, and understanding these differences is key to appreciating their diversity.

Consider the plasmodial slime molds, such as *Physarum polycephalum*, which are known for their striking, network-like structures. When environmental conditions deteriorate—such as reduced food availability or increased dryness—the plasmodium transforms into a sporangium. This process involves the aggregation of the plasmodial mass into a central structure, followed by the differentiation of spore-producing cells. The sporangium then matures, releasing spores that can withstand harsh conditions until favorable environments return. This transformation is a survival strategy, ensuring the slime mold’s persistence across generations.

In contrast, cellular slime molds, like those in the genus *Dictyostelium*, take a different approach to sporangia formation. When nutrients are scarce, individual amoeba-like cells aggregate into a multicellular slug. This slug migrates toward light and then differentiates into a stalked structure, with the sporangium forming at the top. The cells in the stalk sacrifice themselves to elevate the sporangium, which releases spores capable of dispersing and germinating elsewhere. This cooperative behavior highlights the intricate social dynamics within cellular slime molds, making their sporangia formation a remarkable example of collective survival.

For practical observation, enthusiasts can cultivate slime molds on oatmeal-agar plates or damp organic matter to witness sporangia formation firsthand. Plasmodial slime molds often require a few days to a week to form sporangia under optimal conditions (20–25°C and high humidity), while cellular slime molds may take slightly longer due to their multicellular aggregation phase. Patience is key, as the process is highly dependent on environmental cues. Observing these structures under a microscope reveals their intricate details, such as the spore arrangement and the supporting structures, offering a deeper appreciation of their complexity.

While sporangia formation is a universal feature among slime molds, the mechanisms and structures involved vary significantly between groups. This diversity underscores the adaptability of slime molds to their environments and their evolutionary success. Whether through the rapid transformation of a plasmodium or the coordinated effort of cellular aggregation, sporangia formation remains a cornerstone of slime mold biology, offering both scientific intrigue and practical insights into their survival strategies.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Types of Slime Mold Spores

Slime molds, despite their name, are not molds but rather unique organisms that exhibit both fungal and animal-like characteristics. One of the most fascinating aspects of their life cycle is their ability to produce spores, which are crucial for survival and dispersal. However, not all slime molds produce spores in the same way or for the same purpose. Understanding the types of spores they generate provides insight into their diverse reproductive strategies.

Sporangiospores are the most common type of spore produced by slime molds, particularly in the class *Myxomycetes*. These spores are formed within a sporangium, a structure that develops from the fruiting body. When mature, the sporangium releases the spores, which are then dispersed by wind, water, or animals. For example, the *Physarum polycephalum* slime mold produces sporangiospores that can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. To observe this process, place a sample of *Physarum* on a damp surface and watch as the sporangia form and release spores over several days.

In contrast, zygotes serve as a different type of spore in some slime molds, particularly in the class *Dictyosteliida*. Unlike sporangiospores, zygotes are formed through sexual reproduction when two compatible cells fuse. These zygotes have a thick, protective wall that allows them to withstand harsh environmental conditions. For instance, *Dictyostelium discoideum* forms zygotes that can remain dormant in soil for extended periods. To encourage zygote formation, mix two compatible strains of *Dictyostelium* on a nutrient-rich agar plate and monitor for the development of zygospores under a microscope.

Aplanospores and zoospores are less common but equally intriguing spore types found in certain slime molds, such as those in the class *Protosteliida*. Aplanospores are non-motile spores that develop directly from vegetative cells, while zoospores are motile, using flagella to move through water. These spores are typically produced in aquatic or moist environments. To study zoospores, collect a water sample from a damp, decaying log and examine it under a microscope for the characteristic swimming motion of these spores.

Understanding the types of slime mold spores is not just an academic exercise; it has practical applications in fields like agriculture and biotechnology. For example, sporangiospores of *Physarum* have been studied for their potential in bioremediation, as they can break down pollutants. Similarly, the motility of zoospores has inspired research in robotics, mimicking their movement for micro-scale devices. By exploring these spore types, we gain a deeper appreciation for the adaptability and complexity of slime molds, challenging our traditional views of microbial life.

Are All Psilocybe Spore Prints Purple? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Variations

Slime molds, often mistaken for fungi, exhibit a fascinating array of life cycle variations that challenge our understanding of microbial reproduction. While many slime molds do produce spores as part of their life cycle, not all follow this conventional path. For instance, *Physarum polycephalum*, a well-studied acellular slime mold, reproduces through the fragmentation of its plasmodial network, forming multiple independent organisms without the need for spores. This asexual method highlights the diversity within the group and raises questions about the evolutionary pressures shaping these strategies.

Consider the life cycle of *Dictyostelium discoideum*, a social slime mold that exemplifies a unique approach to survival. When food is scarce, individual amoebae aggregate to form a multicellular slug-like structure, which then develops into a fruiting body. Only at this stage are spores produced, dispersed to colonize new environments. This cooperative behavior contrasts sharply with the solitary life cycles of other slime molds, such as *Fuligo septica*, which relies on spores released from sporangia. Understanding these variations requires examining environmental cues, such as nutrient availability and population density, which dictate the choice of reproductive strategy.

For those studying or cultivating slime molds, recognizing these life cycle differences is crucial. For example, if you’re growing *Physarum* in a lab, avoid assuming spore formation as a reproductive endpoint; instead, observe plasmodial growth and fragmentation. Conversely, when working with *Dictyostelium*, monitor aggregation stages by maintaining a cell density of 5–10 million cells/mL and reducing nutrients to trigger development. Practical tips include using non-nutrient agar plates for *Dictyostelium* fruiting body formation and providing oatmeal or cellulose substrates for *Physarum* to thrive.

Comparatively, spore-producing slime molds like *Stemonitis* offer a different set of challenges and opportunities. Their spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving desiccation and extreme temperatures, making them ideal subjects for studying dormancy mechanisms. To induce sporulation in *Stemonitis*, expose cultures to alternating light-dark cycles and gradually decrease humidity. This contrasts with the continuous, spore-independent growth of *Physarum*, which thrives in consistently moist, dark conditions. Such comparisons underscore the adaptability of slime molds to diverse ecological niches.

In conclusion, the life cycle variations among slime molds reflect their evolutionary ingenuity. From spore-dependent species like *Stemonitis* to spore-independent forms like *Physarum*, each strategy is finely tuned to environmental demands. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, understanding these differences not only deepens appreciation for microbial life but also informs practical techniques for cultivation and study. Whether you’re fragmenting a plasmodium or harvesting spores, the key lies in mimicking the natural conditions that drive these unique reproductive pathways.

Are Purple Spore Syringes Better? Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.99 $14.99

Non-Sporulating Slime Molds

Slime molds, often mistaken for fungi, are a diverse group of organisms with unique life cycles. While many slime molds reproduce via spores, a lesser-known subset defies this norm. Non-sporulating slime molds, such as those in the *Physarum* genus, reproduce through fragmentation or the release of motile amoeboid cells instead of forming spores. This deviation challenges the assumption that all slime molds follow a spore-based reproductive strategy, highlighting the complexity and adaptability of these organisms.

Understanding non-sporulating slime molds requires a shift in perspective. Unlike their spore-producing counterparts, these molds rely on asexual methods to propagate. For instance, *Physarum polycephalum* reproduces by breaking into smaller pieces, each capable of growing into a new individual. This process, known as fragmentation, is efficient in stable environments where dispersal is less critical. Additionally, some species release amoeboid cells that can aggregate and form new plasmodia, showcasing an alternative to spore-based reproduction.

From a practical standpoint, studying non-sporulating slime molds offers insights into alternative reproductive strategies in nature. Researchers can cultivate *Physarum* in laboratory settings using simple substrates like oatmeal or agar, making it an accessible model for experiments. To observe fragmentation, place a small piece of the plasmodium on a nutrient-rich surface and monitor its growth over 24–48 hours. For amoeboid cell release, observe the mold under a microscope to see individual cells detaching and moving independently.

Comparatively, non-sporulating slime molds thrive in environments where spore dispersal is less advantageous, such as nutrient-rich, stable habitats. Their reproductive methods prioritize rapid growth and resource utilization over long-distance dispersal. This contrasts with sporulating species, which often inhabit unpredictable environments where spores ensure survival during harsh conditions. By studying these differences, scientists can better understand how environmental pressures shape reproductive strategies.

In conclusion, non-sporulating slime molds challenge the notion that spores are universal in slime mold reproduction. Their unique methods—fragmentation and amoeboid cell release—demonstrate the diversity of life cycles within this group. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, exploring these molds provides a fascinating glimpse into the adaptability of nature. Whether in a lab or the wild, observing their reproductive processes reveals a world where survival strategies are as varied as the organisms themselves.

Troubleshooting Spore Galactic Adventures Installation Issues: Solutions for Existing Spore Users

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors Affecting Spore Production

Slime molds, despite their name, are not molds but rather unique organisms that exhibit both fungal-like and animal-like characteristics. While many slime molds produce spores as part of their life cycle, not all species do. For those that do, spore production is a critical process influenced by a variety of environmental factors. Understanding these factors can provide insights into the ecology and behavior of slime molds, as well as their role in ecosystems.

Analytical Perspective:

Temperature and humidity are two primary environmental factors that significantly impact spore production in slime molds. Most species thrive in temperate to tropical climates, where temperatures range between 15°C and 25°C (59°F to 77°F). Below 10°C (50°F) or above 30°C (86°F), spore production often decreases or halts entirely. Humidity levels are equally crucial; slime molds require moisture to prevent desiccation, with optimal relative humidity ranging from 70% to 90%. For example, *Physarum polycephalum*, a well-studied slime mold, exhibits reduced sporulation under dry conditions, highlighting the sensitivity of these organisms to environmental moisture.

Instructive Approach:

To optimize spore production in slime molds for research or cultivation, consider the following steps:

- Maintain Optimal Temperature: Use a controlled environment, such as an incubator, to keep temperatures between 20°C and 25°C (68°F to 77°F).

- Regulate Humidity: Employ a humidifier or misting system to ensure relative humidity remains above 70%.

- Provide Substrate: Slime molds often require organic matter, such as decaying wood or leaf litter, as a substrate for growth and sporulation.

- Monitor Light Exposure: While slime molds are not photosynthetic, some species may respond to light cues. Indirect, diffused light is generally sufficient.

Comparative Insight:

Unlike fungi, which often produce spores in response to nutrient depletion, slime molds are more influenced by physical environmental conditions. For instance, while fungi like *Aspergillus* can sporulate under a wide range of temperatures, slime molds are more restricted. Additionally, slime molds lack the complex hyphae networks of fungi, relying instead on plasmodial stages that are highly sensitive to environmental changes. This sensitivity makes slime molds excellent bioindicators for monitoring ecosystem health, as changes in spore production can signal shifts in environmental conditions.

Descriptive Example:

In a forest ecosystem, slime molds like *Stemonitis* species often produce spores on decaying logs or leaf litter during the wet season. The combination of high humidity, moderate temperatures, and abundant organic matter creates an ideal environment for sporulation. Conversely, during dry periods, these organisms may enter a dormant phase, reducing spore production to conserve energy. This seasonal pattern underscores the adaptive strategies of slime molds in response to environmental fluctuations.

Persuasive Takeaway:

Understanding the environmental factors affecting spore production in slime molds is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications for conservation and biotechnology. By manipulating these factors, researchers can cultivate slime molds for studying their unique behaviors, such as problem-solving and memory-like capabilities. Moreover, protecting the habitats that support optimal conditions for slime mold sporulation can contribute to biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. Whether in a laboratory or the wild, recognizing the delicate balance of temperature, humidity, and substrate is key to appreciating and harnessing the potential of these fascinating organisms.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Headaches? Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all slime molds produce spores as part of their life cycle, though the methods and structures involved can vary between species.

Slime molds release spores through specialized structures like sporangia or spore-bearing bodies, which rupture or disintegrate to disperse the spores.

No, the spores of slime molds differ in size, shape, and structure depending on the species and their specific reproductive strategies.

While spores are the primary method of reproduction for slime molds, some species can also reproduce asexually through fragmentation or other vegetative means.