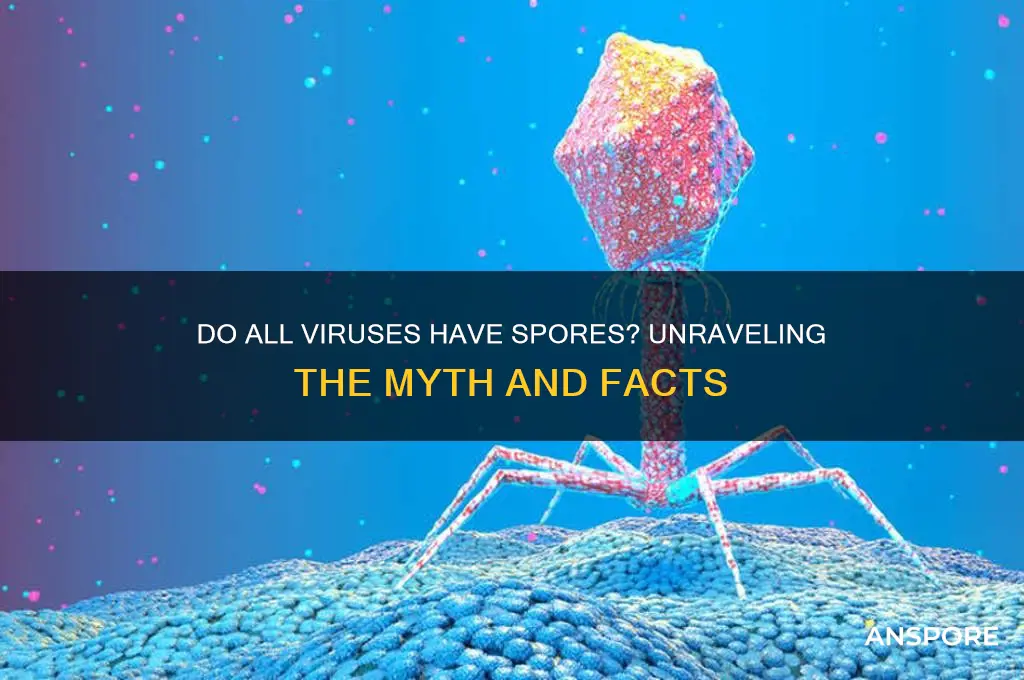

The question of whether all viruses have spores is a common misconception, as spores are actually associated with bacteria, fungi, and some plants, not viruses. Viruses are distinct biological entities that lack cellular structure and reproduce by hijacking host cells to replicate their genetic material. Unlike spore-forming organisms, which produce dormant, resistant structures to survive harsh conditions, viruses rely on protective protein coats (capsids) or envelopes to endure external environments. Therefore, viruses do not form spores, and understanding this distinction is crucial for accurately categorizing and studying these microscopic entities.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do all viruses have spores? | No |

| Viruses that form spores | None (viruses do not form spores) |

| Spores | Formed by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants as a survival mechanism |

| Virus survival mechanisms | May include formation of viral crystals, biofilms, or persistence in host cells |

| Distinction between viruses and spore-formers | Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, whereas spore-formers are typically prokaryotic or eukaryotic organisms |

| Examples of spore-forming organisms | Bacillus (bacteria), Clostridium (bacteria), and fungi like Aspergillus |

| Virus structure | Consists of genetic material (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a protein capsid, sometimes with an envelope |

| Spore structure | A dormant, highly resistant cell type with a thick protective coating |

| Environmental resistance | Spores are highly resistant to environmental stresses, while viruses rely on host cells for survival |

| Reproduction | Viruses replicate inside host cells, whereas spores germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Virus vs. Bacteria Spores: Viruses lack spores; only bacteria form spores for survival in harsh conditions

- Virus Survival Mechanisms: Viruses survive via host cells or external protection, not spore formation

- Spores in Microorganisms: Spores are exclusive to certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, not viruses

- Virus Structure Differences: Viruses consist of genetic material and protein coats, lacking spore-like structures

- Misconceptions About Viruses: Confusion arises from comparing viral persistence to bacterial spore resilience

Virus vs. Bacteria Spores: Viruses lack spores; only bacteria form spores for survival in harsh conditions

Viruses and bacteria are both microscopic entities, yet they differ fundamentally in their survival strategies. While bacteria can form spores to endure extreme conditions, viruses lack this ability entirely. This distinction is critical for understanding how these organisms persist in environments ranging from scorching deserts to freezing tundra. Bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis*, are highly resistant to heat, radiation, and desiccation, allowing them to remain dormant for years until conditions improve. Viruses, on the other hand, rely on host cells for replication and survival, making them vulnerable outside a living organism.

Consider the practical implications of this difference in medical and environmental contexts. For instance, sterilizing equipment in hospitals often requires autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to destroy bacterial spores, which are far more resilient than vegetative bacteria or viruses. However, viruses like influenza or SARS-CoV-2 can be inactivated by simpler methods, such as alcohol-based disinfectants or soap, as they lack the protective spore structure. This highlights the importance of tailoring disinfection protocols to the specific pathogen in question.

From an evolutionary perspective, the absence of spores in viruses is tied to their parasitic nature. Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, meaning they cannot survive or replicate without a host. Their genetic material is encased in a protein coat, which offers limited protection compared to the robust, multilayered structure of a bacterial spore. Bacteria, being self-sufficient organisms, evolved sporulation as a survival mechanism to withstand environmental stresses. Viruses, however, have evolved alternative strategies, such as rapid mutation and host-switching, to ensure their persistence.

For those working in fields like microbiology or public health, understanding this distinction is crucial. For example, when investigating a waterborne outbreak, knowing that bacterial spores can survive in water for extended periods, while viruses degrade more quickly, can guide testing and treatment strategies. Similarly, in food safety, the presence of bacterial spores in canned goods necessitates high-temperature processing, whereas viral contamination is less likely to survive standard cooking temperatures.

In summary, while both viruses and bacteria are microscopic, their survival mechanisms diverge sharply. Bacteria form spores to endure harsh conditions, while viruses lack this ability, relying instead on host cells for survival. This difference has profound implications for disinfection, medical treatment, and environmental persistence, underscoring the need for targeted approaches in managing these distinct pathogens.

Mold Spores and Diarrhea: Uncovering the Surprising Health Connection

You may want to see also

Virus Survival Mechanisms: Viruses survive via host cells or external protection, not spore formation

Viruses, unlike bacteria and fungi, do not form spores as a survival mechanism. This fundamental distinction is rooted in their biological nature: viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, entirely dependent on host cells for replication and survival. While spore formation is a well-known strategy for microorganisms to endure harsh conditions, viruses employ alternative methods to persist in environments outside their hosts. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for combating viral transmission and designing effective disinfection strategies.

One primary survival mechanism for viruses is their ability to remain dormant within host cells. For instance, herpesviruses can establish latency in nerve cells, reactivating under specific triggers like stress or immunosuppression. This intracellular hiding ensures long-term survival without the need for spore-like structures. Similarly, HIV integrates its genetic material into the host’s DNA, lying dormant until conditions favor replication. Such strategies highlight the virus’s reliance on the host’s cellular machinery rather than external protective forms.

Externally, viruses rely on protective envelopes or protein capsids to withstand environmental challenges. Enveloped viruses, like influenza and SARS-CoV-2, are more susceptible to desiccation and disinfectants but can survive for hours to days on surfaces due to their lipid bilayer. Non-enveloped viruses, such as norovirus and poliovirus, are more resilient, surviving for weeks in water or on surfaces due to their robust protein capsids. These structural adaptations provide a form of external protection, but they are not equivalent to spores, which are metabolically inactive and highly resistant to extreme conditions.

Practical implications of these survival mechanisms are evident in disinfection protocols. Enveloped viruses are effectively inactivated by alcohol-based sanitizers (at least 70% ethanol or isopropanol), while non-enveloped viruses require more robust methods, such as bleach solutions (1:10 dilution of household bleach) or heat treatment (60°C for 30 minutes). Understanding these differences is essential for healthcare settings, food safety, and public health interventions. For example, surfaces contaminated with norovirus require thorough cleaning with bleach, whereas alcohol-based hand sanitizers are sufficient for reducing SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

In summary, viruses survive through host cell dependency and structural resilience, not spore formation. Their survival strategies are tailored to their parasitic nature, relying on either intracellular dormancy or external protective layers. This knowledge informs targeted disinfection practices, emphasizing the importance of adapting methods to the specific virus type. By focusing on these mechanisms, we can more effectively mitigate viral spread and protect public health.

Could an Asteroid Strike a Planet in Spore? Exploring the Possibility

You may want to see also

Spores in Microorganisms: Spores are exclusive to certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, not viruses

Spores are nature’s survival capsules, but they are not universal across all microorganisms. While bacteria, fungi, and certain plants rely on spores to endure harsh conditions, viruses are conspicuously absent from this adaptive strategy. This distinction is rooted in the fundamental biology of these organisms. Bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* and fungi such as *Aspergillus* produce spores as dormant, resilient forms to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemicals. Plants, too, use spores in their reproductive cycles, as seen in ferns and mosses. Viruses, however, lack the cellular machinery to produce spores; they are obligate intracellular parasites that depend on host cells for replication. Understanding this exclusivity helps clarify why antiviral strategies differ from those targeting spore-forming organisms.

To illustrate, consider the spore-forming bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, which can survive in soil for years before germinating under favorable conditions. In contrast, viruses like influenza or SARS-CoV-2 rely on rapid transmission and host susceptibility rather than long-term environmental persistence. This difference is critical in public health: while bacterial spores can be inactivated by autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, viruses are typically neutralized by disinfectants like 70% ethanol or bleach solutions. Misapplying spore-targeted methods to viruses could lead to ineffective disinfection, underscoring the importance of tailoring interventions to the organism’s biology.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between spore-forming and non-spore-forming microorganisms is essential in fields like food safety and medicine. For instance, canned foods are heated to 121°C to destroy bacterial spores, a process known as botulinum cook, which is unnecessary for viral contamination. Similarly, in healthcare settings, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* require specialized cleaning protocols, such as using chlorine-based disinfectants, whereas viral pathogens are effectively managed with standard alcohol-based sanitizers. This specificity ensures resources are allocated efficiently and risks are mitigated appropriately.

Finally, the absence of spores in viruses highlights their evolutionary strategy: rapid mutation and host dependency. Unlike spore-forming organisms, which invest energy in long-term survival, viruses prioritize replication speed and genetic adaptability. This distinction not only explains why viruses dominate acute infectious diseases but also informs vaccine development. While bacterial spores can be targeted by vaccines like the anthrax vaccine, viral vaccines, such as the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, focus on neutralizing viral proteins. Recognizing these differences empowers scientists and practitioners to combat microbial threats with precision and efficacy.

How Wind Disperses Spores: Exploring Nature's Aerial Seed Scattering

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Virus Structure Differences: Viruses consist of genetic material and protein coats, lacking spore-like structures

Viruses, unlike bacteria and fungi, do not produce spores. This fundamental distinction lies in their structural simplicity. A virus is essentially a package of genetic material—either DNA or RNA—encased in a protein coat called a capsid. Some viruses also have an outer lipid envelope derived from the host cell membrane. This minimalistic design is tailored for one purpose: to infiltrate host cells and hijack their machinery for replication. Spores, on the other hand, are specialized survival structures produced by certain bacteria and fungi, designed to endure harsh conditions like extreme temperatures or desiccation. Viruses lack the cellular machinery to create such complex structures, relying instead on rapid replication and host-to-host transmission for survival.

Consider the influenza virus, a common example of an enveloped virus. Its structure consists of RNA segments encased in a capsid, surrounded by a lipid envelope studded with glycoproteins. This design allows it to fuse with host cell membranes and inject its genetic material. However, without a cell, the virus is fragile and degrades quickly outside a host. Contrast this with bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*, which can remain dormant for years in soil or food, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate. The absence of spore-like structures in viruses underscores their dependence on living hosts for survival and propagation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this structural difference has significant implications for disinfection and sterilization. Viruses are generally susceptible to common disinfectants like alcohol and bleach, which disrupt their protein coats or lipid envelopes. For instance, a 70% ethanol solution can inactivate most enveloped viruses within seconds. However, bacterial spores require more aggressive methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure complete destruction. This highlights the importance of tailoring sterilization protocols to the specific pathogen in question, rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach.

Finally, the lack of spore-like structures in viruses also influences their evolutionary strategies. While spores allow bacteria and fungi to persist in adverse environments, viruses must continuously infect hosts to survive. This has driven the evolution of remarkable adaptability in viruses, such as rapid mutation rates and the ability to cross species barriers. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for COVID-19, likely originated in bats before adapting to humans. Such adaptability poses unique challenges for public health, as it necessitates ongoing surveillance and vaccine updates to keep pace with viral evolution. In essence, the absence of spores in viruses shapes not only their structure but also their ecological and epidemiological dynamics.

Can Tetanus Spores Survive in Oxygen? Unraveling the Myth

You may want to see also

Misconceptions About Viruses: Confusion arises from comparing viral persistence to bacterial spore resilience

Viruses and bacteria are fundamentally different entities, yet their mechanisms of survival are often conflated, leading to misconceptions about viral persistence. Unlike bacteria, which can form highly resilient spores to endure harsh conditions, viruses do not produce spores. Instead, viruses rely on host cells for replication and survival, remaining dormant in extracellular environments as virions. This distinction is critical, as bacterial spores can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemicals, whereas viral persistence outside a host is limited and highly dependent on environmental factors like humidity and surface type. For instance, while *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling temperatures, the influenza virus typically remains infectious on surfaces for only 24 to 48 hours.

A common misconception arises from equating viral persistence with bacterial spore resilience, particularly in discussions about disinfection and sterilization. Bacterial spores require specialized methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure their destruction. In contrast, most viruses are inactivated by standard disinfectants like 70% ethanol or sodium hypochlorite (bleach) within minutes. However, the confusion persists, especially in public health contexts, where terms like "viral spores" are mistakenly used. This misnomer can lead to over-reliance on extreme measures for viral decontamination, which are unnecessary and resource-intensive. For example, UV-C light effectively inactivates viruses on surfaces, but it is not required to "kill spores" as it would for bacteria.

To address this confusion, it’s essential to educate on the biological differences between viruses and bacteria. Viruses lack the cellular machinery to form spores; their survival strategies include integrating into host genomes (e.g., herpesviruses) or persisting in protected environments (e.g., hepatitis B virus in dried blood). Bacterial spores, on the other hand, are metabolically dormant cells encased in a protective coat, capable of reviving under favorable conditions. Practical tips for distinguishing these concepts include focusing on the term "viral particles" instead of "spores" and understanding that viral disinfection protocols are generally less stringent than those for bacterial spores. For instance, hand sanitizers with 60% alcohol are sufficient for viruses but ineffective against *Bacillus anthracis* spores.

The takeaway is clear: viral persistence and bacterial spore resilience are distinct phenomena, and conflating them undermines accurate public health practices. While bacterial spores demand extreme measures for eradication, viruses are more susceptible to common disinfectants and environmental degradation. By clarifying these differences, individuals and professionals can implement targeted strategies for infection control, avoiding unnecessary panic or over-treatment. For example, in healthcare settings, knowing that viruses like SARS-CoV-2 are inactivated by routine cleaning protocols, while *C. difficile* spores require sporicidal agents, ensures efficient resource allocation and patient safety.

Injecting Spores into Coco Coir: Benefits, Techniques, and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, viruses do not produce spores. Spores are a survival structure produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, not by viruses.

Viruses do not form dormant structures like spores. Instead, they can remain latent within host cells or survive outside hosts in a protective protein coat (capsid) until they infect a new host.

While viruses do not form spores, some can survive in harsh conditions for extended periods, similar to spore-forming bacteria. However, this is due to their capsid structure, not spore formation.