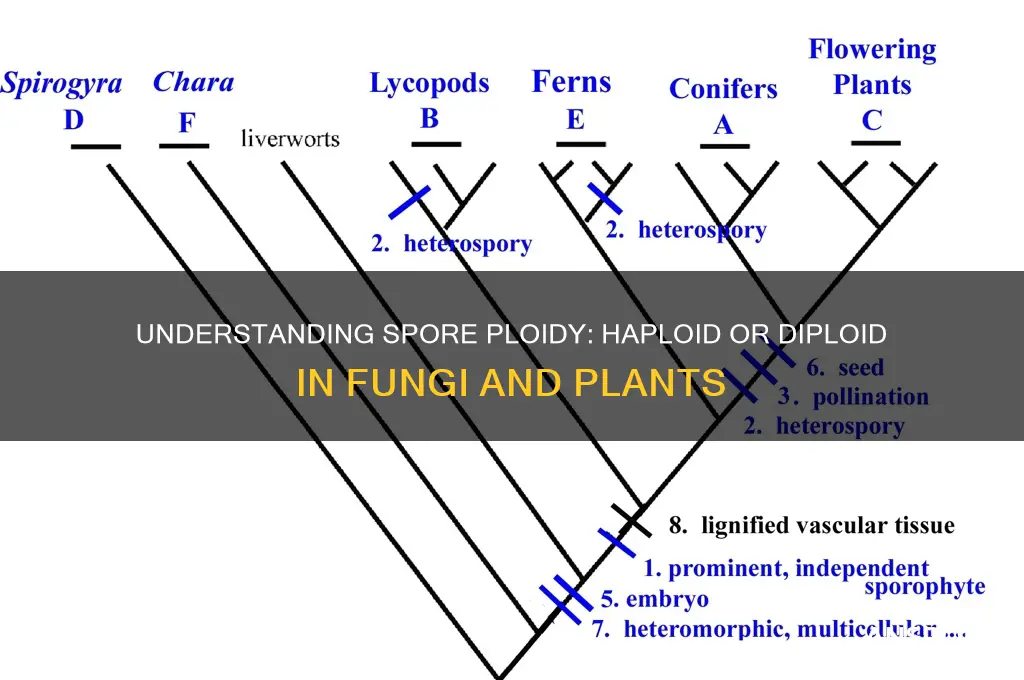

The question of whether a spore is haploid or diploid is fundamental to understanding the life cycles of various organisms, particularly in fungi, plants, and some protists. Spores are reproductive structures that play a crucial role in dispersal and survival, but their ploidy—whether they contain a single set of chromosomes (haploid) or two sets (diploid)—varies depending on the organism and its life cycle stage. In most fungi and non-vascular plants, spores are typically haploid, produced by meiosis and developing into haploid individuals. However, in vascular plants like ferns and seed plants, spores can be haploid (e.g., pollen and spores in ferns) or diploid (e.g., spores in some algae and certain fungal species). Understanding the ploidy of spores is essential for grasping the alternation of generations and reproductive strategies in these organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Type | Spores can be either haploid or diploid depending on the organism and life cycle stage. |

| Haploid Spores | Produced in haploid organisms (e.g., fungi, some plants) via meiosis; contain a single set of chromosomes (n). |

| Diploid Spores | Produced in diploid organisms (e.g., some algae, certain fungi) via mitosis; contain two sets of chromosomes (2n). |

| Function | Haploid spores typically germinate into gametophytes, while diploid spores may directly develop into sporophytes or other structures. |

| Examples | Haploid: Fungal spores, pollen grains in plants. Diploid: Spores in some algae, certain fungal species. |

| Life Cycle Role | Haploid spores are common in alternation of generations, while diploid spores are less frequent and specific to certain life cycles. |

| Chromosome Number | Haploid (n) vs. Diploid (2n). |

| Reproductive Strategy | Haploid spores often involve sexual reproduction, while diploid spores may involve asexual or vegetative reproduction. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: Spores develop via meiosis, ensuring haploid genetic content for diversity

- Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Most spores are haploid; diploid spores occur in specific life cycles

- Fungal Spores: Fungi produce haploid spores for reproduction and dispersal

- Plant Spores: Plants have alternating haploid (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) phases

- Spore Function: Haploid spores fuse to form diploid zygotes, restarting the cycle

Spore Formation Process: Spores develop via meiosis, ensuring haploid genetic content for diversity

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are pivotal in the reproductive strategies of many organisms, particularly fungi, plants, and some protozoa. Their formation is a fascinating biological process that hinges on meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. This reduction is crucial because it ensures that spores carry a single set of chromosomes, setting the stage for genetic diversity when they germinate and fuse with other haploid cells. Understanding this process not only sheds light on the life cycles of these organisms but also highlights the evolutionary advantages of haploidy in spore-producing species.

The spore formation process begins with a diploid cell, which contains two sets of chromosomes, one from each parent. Through meiosis, this cell undergoes two rounds of division, producing four haploid spores. Each spore is genetically unique due to the shuffling of genetic material during meiosis, a phenomenon known as genetic recombination. This diversity is a survival strategy, allowing species to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases. For instance, in fungi like *Aspergillus*, meiosis ensures that each spore has a distinct genetic makeup, increasing the likelihood that at least some will thrive in varying conditions.

From a practical standpoint, the haploid nature of spores is exploited in agriculture and biotechnology. In plant breeding, haploid spores are used to create homozygous lines, which are essential for developing new crop varieties with desirable traits. For example, in maize breeding, haploid induction techniques accelerate the production of inbred lines, reducing the time required to develop new hybrids. Similarly, in biotechnology, haploid spores of fungi like *Yarrowia lipolytica* are engineered to produce biofuels and pharmaceuticals, leveraging their genetic simplicity for efficient metabolic engineering.

However, the haploid state of spores is not without challenges. Haploid organisms are more susceptible to genetic mutations because they lack a second set of chromosomes to mask deleterious alleles. To mitigate this, many spore-producing organisms have evolved mechanisms to repair DNA damage and maintain genetic integrity. For example, fungi like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) have robust DNA repair pathways that ensure the survival of their haploid spores. Understanding these mechanisms can inform strategies for preserving spore viability in storage and enhancing their resilience in industrial applications.

In conclusion, the spore formation process, driven by meiosis, is a masterclass in ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. By producing haploid spores, organisms maximize their evolutionary potential, enabling them to colonize new environments and resist threats. Whether in natural ecosystems or biotechnological applications, the haploid nature of spores is both a challenge and an opportunity, offering insights into the intricate balance between genetic stability and innovation. For researchers and practitioners, harnessing this process requires a deep understanding of its mechanisms and the practical implications of haploidy in spore-producing species.

Do Gram-Negative Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling the Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Most spores are haploid; diploid spores occur in specific life cycles

Spores, the reproductive units of many organisms, predominantly exist in a haploid state, carrying a single set of chromosomes. This is a fundamental characteristic of the life cycles of fungi, plants, and some protists, where haploid spores germinate into haploid individuals that later undergo fertilization to form diploid zygotes. For instance, in the life cycle of a fern, spores produced by the sporophyte (diploid) generation develop into gametophytes (haploid), which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction. This haploid dominance is a key evolutionary strategy, allowing for genetic diversity through recombination during fertilization.

However, diploid spores are not entirely absent from nature, though they are less common and occur in specific life cycles. Certain fungi, like some basidiomycetes, produce diploid spores as part of their reproductive strategy. These diploid spores can directly germinate into diploid individuals, bypassing the haploid phase. This adaptation is advantageous in stable environments where rapid growth and colonization are prioritized over genetic diversity. Understanding this distinction is crucial for fields like mycology and botany, where life cycle variations influence ecological roles and reproductive success.

To illustrate, consider the life cycle of a mushroom-forming fungus. In the typical dikaryotic phase, haploid nuclei coexist in the same cell without fusing, but during spore formation, diploid spores may be produced under specific conditions. These diploid spores can then germinate into diploid mycelium, which may later undergo meiosis to return to the haploid state. This flexibility in ploidy levels highlights the adaptability of spore-producing organisms to different environmental pressures.

For practical applications, such as in agriculture or biotechnology, recognizing whether spores are haploid or diploid is essential. Haploid spores are often used in genetic studies because their single set of chromosomes simplifies analysis. For example, in plant breeding, haploid spores derived from microspores can be cultured to produce doubled haploid plants, which are genetically uniform and valuable for crop improvement. Conversely, diploid spores may be utilized in fungal fermentation processes where stability and consistency are required.

In summary, while most spores are haploid, diploid spores emerge in specialized life cycles, offering unique advantages in specific contexts. This duality underscores the complexity and diversity of reproductive strategies in spore-producing organisms. By understanding these differences, researchers and practitioners can harness the potential of spores more effectively, whether in scientific inquiry or applied fields.

Lysol's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Ringworm Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Fungi produce haploid spores for reproduction and dispersal

Fungi, a diverse group of organisms, have evolved a unique reproductive strategy centered around the production of haploid spores. Unlike diploid cells, which contain two sets of chromosomes, haploid cells carry a single set, making them lighter and more adaptable for dispersal. This characteristic is crucial for fungi, as it allows them to colonize new environments efficiently. For instance, when a mushroom releases its spores, each one is genetically distinct and capable of growing into a new individual under favorable conditions. This haploid nature ensures genetic diversity, a key factor in the survival and adaptability of fungal species across various ecosystems.

Consider the life cycle of a common fungus like *Aspergillus*. It begins with the germination of a haploid spore, which grows into a network of filaments called hyphae. These hyphae then produce specialized structures, such as conidiophores, which bear new haploid spores. This asexual reproduction phase is rapid and efficient, enabling the fungus to spread quickly in stable environments. However, fungi also have a sexual phase where haploid cells from two compatible individuals fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote undergoes meiosis to produce new haploid spores, ensuring genetic recombination and long-term evolutionary success.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of fungal spores is essential for industries like agriculture and medicine. For example, farmers use fungicides to target specific stages of the fungal life cycle, often focusing on spore production to prevent crop diseases. Similarly, in medical mycology, knowing that fungal pathogens like *Candida* and *Cryptococcus* disperse via haploid spores helps in developing targeted antifungal therapies. By disrupting spore formation or germination, these treatments can effectively control fungal infections without harming the host.

Comparatively, the haploid spore strategy contrasts with the reproductive methods of plants and animals, which often rely on diploid structures for dispersal. For instance, plant seeds are typically diploid, containing genetic material from both parents. Fungi, however, prioritize lightweight, genetically diverse haploid spores for wind or water dispersal, a strategy that maximizes their reach and survival in unpredictable environments. This difference highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi, which have thrived for millions of years by leveraging simplicity and adaptability.

In conclusion, the production of haploid spores is a cornerstone of fungal reproduction and dispersal. This strategy not only ensures genetic diversity but also enables fungi to colonize diverse habitats efficiently. Whether in natural ecosystems or human-managed environments, understanding this unique aspect of fungal biology is crucial for managing fungal populations effectively. By studying fungal spores, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of these organisms, informing practices in agriculture, medicine, and beyond.

Understanding Milky Spore: A Natural Grub Control Solution for Lawns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Plant Spores: Plants have alternating haploid (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) phases

Plants exhibit a unique life cycle characterized by alternating generations, where the haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases play distinct roles. In this cycle, spores are the pivotal link between these phases. Spores are haploid cells produced by the sporophyte through a process called meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number by half. These spores then germinate to form the gametophyte, a haploid organism responsible for producing gametes (sperm and egg cells). Understanding this alternation of generations is crucial for grasping the complexity of plant reproduction and evolution.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The visible fern plant we often see is the diploid sporophyte generation. On the underside of its fronds, it produces spore cases (sporangia) that release haploid spores. These spores develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, which are often hidden from plain sight. The gametophyte, being haploid, produces both sperm and egg cells. After fertilization, the resulting zygote grows into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, key factors in the success of plant species across diverse environments.

From an analytical perspective, the haploid-diploid alternation in plants is a strategic evolutionary adaptation. The haploid phase (gametophyte) is typically short-lived and dependent on moisture, limiting its exposure to environmental stressors. In contrast, the diploid phase (sporophyte) is more robust and long-lived, better equipped to survive harsh conditions. This division of labor allows plants to maximize reproductive efficiency while minimizing risks. For instance, in mosses, the gametophyte is the dominant phase, while in more complex plants like angiosperms, the sporophyte dominates, reflecting evolutionary trends toward greater complexity and resilience.

For gardeners and botanists, understanding this cycle has practical implications. For example, when propagating ferns, knowing that spores are haploid and require specific conditions to germinate can improve success rates. Spores need a humid, shaded environment to develop into gametophytes, which then rely on water for sperm to reach the egg. Similarly, in seed-producing plants, the sporophyte phase is what we cultivate, but the haploid gametophyte (within the flower) is critical for fertilization. This knowledge can guide practices like pollination management or spore-based propagation, ensuring healthier and more productive plants.

In conclusion, the alternation between haploid and diploid phases in plant spores is a fascinating and functional aspect of plant biology. It not only highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of plants but also offers practical insights for horticulture and conservation. By recognizing the roles of spores, gametophytes, and sporophytes, we can better appreciate the intricate balance that sustains plant life and apply this knowledge to real-world applications. Whether studying ferns or cultivating crops, this understanding bridges the gap between theory and practice, enriching our interaction with the botanical world.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Propagation: Effective Techniques to Spread Spores

You may want to see also

Spore Function: Haploid spores fuse to form diploid zygotes, restarting the cycle

Spores, often misunderstood as mere survival structures, play a pivotal role in the life cycles of plants, fungi, and some protists by bridging the gap between haploid and diploid phases. In organisms like ferns and mushrooms, spores are unequivocally haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes. This haploid nature is critical because when spores germinate, they grow into gametophytes—structures that produce gametes (sperm and eggs). The fusion of these gametes, each haploid, results in a diploid zygote, effectively restarting the life cycle. This process, known as alternation of generations, ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in changing environments.

Consider the fern life cycle as a practical example. A haploid spore lands on moist soil, germinates, and develops into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte produces sperm and eggs. When sperm fertilizes an egg, a diploid zygote forms, which grows into the familiar fern plant (the sporophyte). The sporophyte then produces spores through meiosis, completing the cycle. This alternation between haploid and diploid phases is a hallmark of spore function, showcasing how spores act as both endpoints and starting points in the reproductive journey.

From an analytical perspective, the haploid nature of spores serves as a strategic evolutionary advantage. By producing haploid spores, organisms reduce the genetic material in their dispersive stage, minimizing the risk of mutations during environmental exposure. Once the spore germinates and grows into a gametophyte, the fusion of gametes reintroduces diploidy, restoring genetic robustness. This two-step process balances vulnerability and stability, ensuring survival across generations. For instance, in fungi like *Aspergillus*, haploid spores (conidia) are lightweight and easily dispersed, allowing the organism to colonize new habitats efficiently.

For those studying or working with spore-producing organisms, understanding this cycle is crucial. In agriculture, knowing that spores are haploid helps in predicting disease spread in crops like wheat or rice, where fungal spores (e.g., rust fungi) can rapidly infect plants. In horticulture, manipulating spore germination conditions can enhance fern or moss growth. A practical tip: maintain high humidity (70–90%) and moderate temperatures (20–25°C) to encourage spore germination in controlled environments. This knowledge also aids in conservation efforts, as preserving spore-producing plants ensures biodiversity in ecosystems.

In conclusion, the function of spores as haploid entities that fuse to form diploid zygotes is a cornerstone of life cycles in many organisms. This mechanism not only ensures genetic diversity but also provides resilience against environmental challenges. Whether in research, agriculture, or conservation, recognizing the role of spores in restarting the life cycle offers actionable insights for practical applications. By focusing on this specific aspect of spore function, one gains a deeper appreciation for the intricate balance between haploidy and diploidy in nature.

Understanding Milky Spores: A Natural Solution for Grub Control in Lawns

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore is haploid, meaning it contains a single set of chromosomes.

Spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells.

Yes, all spores, whether they are from fungi, plants, or other organisms, are haploid.

Haploid spores germinate and grow into haploid individuals or structures, which then undergo fertilization to restore the diploid phase in the life cycle.

No, spores are always haploid. Diploid cells are formed after fertilization, not during spore production.