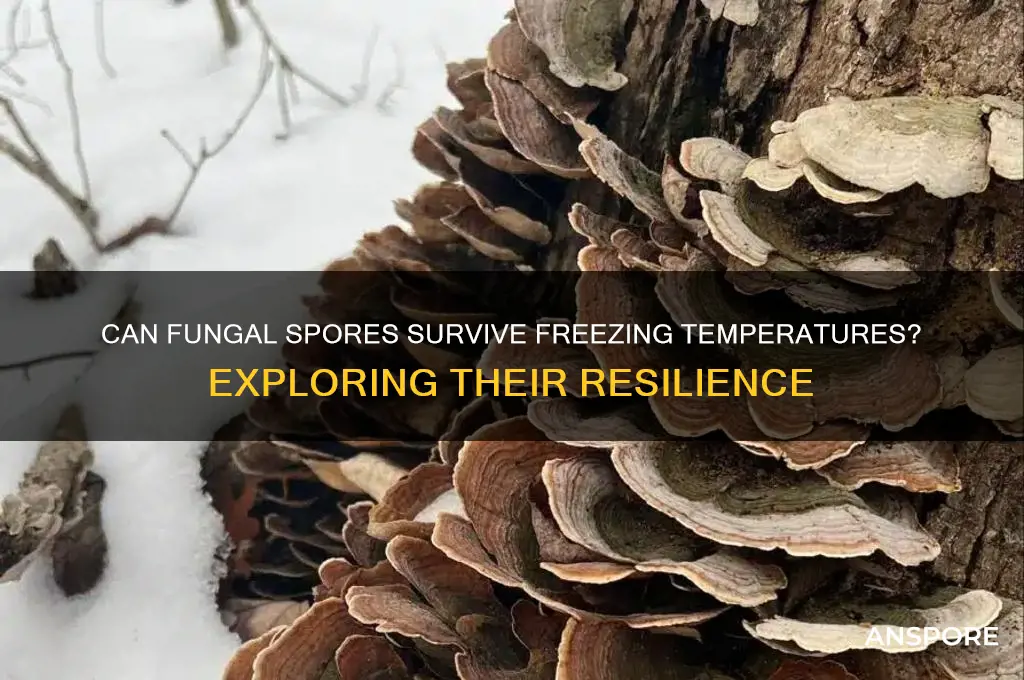

Fungal spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, play a crucial role in their life cycle and dispersal. One common question that arises is whether these spores can freeze and, if so, what impact freezing has on their viability. Fungal spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving a wide range of environmental conditions, including extreme temperatures. While freezing can affect their structure and function, many fungal spores are able to withstand freezing temperatures through mechanisms such as cryoprotectants and desiccation tolerance. Understanding how fungal spores respond to freezing is essential for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology, as it influences their persistence in the environment, their role in disease transmission, and their potential use in biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Freezing Tolerance | Many fungal spores can survive freezing temperatures, with some species tolerating temperatures as low as -80°C. |

| Survival Mechanism | Spores enter a dormant state, reducing metabolic activity and protecting cellular structures with compatible solutes (e.g., glycerol, trehalose). |

| Desiccation Tolerance | Freezing often involves desiccation, and fungal spores are highly resistant to water loss due to their thick cell walls. |

| Cell Wall Composition | The cell wall, composed of chitin, glucans, and other polymers, provides structural integrity and protection during freezing. |

| Revival After Thawing | Spores can revive and germinate upon thawing, given suitable environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, nutrients). |

| Species Variability | Tolerance to freezing varies widely among fungal species, with psychrophilic fungi being more resistant than others. |

| Ecological Significance | Freezing tolerance allows fungi to survive in extreme environments, such as polar regions and high altitudes. |

| Applications | Understanding freezing tolerance in fungal spores has implications for food preservation, biotechnology, and astrobiology. |

Explore related products

$22.49 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Freezing Tolerance Mechanisms: How fungal spores survive freezing temperatures through protective mechanisms like antifreeze proteins

- Impact on Viability: Effects of freezing on spore germination rates and long-term survival

- Cryopreservation Techniques: Methods to preserve fungal spores at ultra-low temperatures for research and agriculture

- Ecological Significance: Role of freezing in spore dispersal and survival in cold environments

- Species Variability: Differences in freezing resistance among fungal species and their adaptations

Freezing Tolerance Mechanisms: How fungal spores survive freezing temperatures through protective mechanisms like antifreeze proteins

Fungal spores, often associated with decay and disease, harbor a remarkable ability to withstand freezing temperatures, a trait that ensures their survival across diverse ecosystems. This resilience is not accidental but the result of sophisticated freezing tolerance mechanisms, chief among them the production of antifreeze proteins (AFPs). These proteins bind to ice crystals, inhibiting their growth and preventing cellular damage, a process critical for spore longevity in cold environments. Unlike animals, which rely on behavioral adaptations or migration, fungi are sessile organisms, making such biochemical strategies essential for their persistence.

The role of AFPs in fungal spores is both precise and multifaceted. These proteins function by adsorbing to the surface of ice crystals, lowering the non-colligative freezing point of water without affecting its melting point—a phenomenon known as thermal hysteresis. This mechanism allows spores to remain viable even when temperatures drop below the freezing point of water. For instance, species like *Mortierella alpina* produce AFPs that enable survival in subzero conditions, a trait particularly advantageous in polar or alpine regions. The dosage and type of AFP produced vary among species, reflecting their evolutionary adaptation to specific environmental pressures.

To understand the practical implications, consider the agricultural sector, where fungal spores can either be beneficial (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi enhancing plant growth) or detrimental (e.g., pathogens causing crop loss). Knowledge of freezing tolerance mechanisms can inform strategies for both preservation and eradication. For example, storing beneficial fungal spores at temperatures just below their freezing threshold, coupled with controlled AFP expression, could enhance their shelf life. Conversely, disrupting AFP production in pathogenic fungi might offer a novel biocontrol method, reducing their survival in cold climates.

A comparative analysis reveals that fungal AFPs differ structurally and functionally from those found in fish, insects, or plants, highlighting convergent evolution in response to freezing stress. While fish AFPs are typically hyperactive and small, fungal AFPs often exhibit moderate thermal hysteresis but are more versatile in their interactions with ice. This diversity underscores the adaptability of fungi, which have evolved unique solutions to shared environmental challenges. For researchers, this presents an opportunity to engineer AFPs for industrial applications, such as cryopreservation of organs or food, by drawing inspiration from fungal models.

In conclusion, the survival of fungal spores in freezing temperatures is a testament to the ingenuity of nature’s biochemical toolkit. Antifreeze proteins, though just one component of this toolkit, play a pivotal role by directly mitigating ice-induced damage. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can unlock practical applications ranging from agriculture to biotechnology, while also gaining deeper insights into the evolutionary strategies of fungi. Whether preserving beneficial species or combating pathogens, understanding freezing tolerance in fungal spores offers a pathway to harnessing their resilience for human benefit.

Beyond Fungi: Exploring the Diverse World of Spore-Producing Organisms

You may want to see also

Impact on Viability: Effects of freezing on spore germination rates and long-term survival

Freezing temperatures can significantly alter the viability of fungal spores, affecting both their germination rates and long-term survival. Research indicates that while some fungal species exhibit remarkable resilience to freezing, others may suffer reduced viability or complete inactivation. For instance, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* spores have been shown to tolerate freezing conditions, with germination rates often remaining stable after exposure to temperatures as low as -20°C. However, species like *Fusarium* and *Rhizoctonia* may experience up to a 50% reduction in germination after prolonged freezing, highlighting the variability in fungal responses.

To mitigate the adverse effects of freezing on spore viability, specific strategies can be employed. Gradual freezing, as opposed to rapid freezing, has been observed to enhance survival rates in some species by allowing spores to acclimate to low temperatures. Additionally, the inclusion of cryoprotectants such as glycerol or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations of 5–10% can protect cellular structures during freezing. For long-term storage, spores should be suspended in a solution containing 10% skim milk or 15% glycerol before freezing at -80°C, ensuring optimal preservation of viability for up to 10 years.

A comparative analysis of freezing methods reveals that lyophilization (freeze-drying) often outperforms conventional freezing in maintaining spore viability. This technique removes water through sublimation, minimizing ice crystal formation that can damage cellular membranes. Studies show that lyophilized spores of *Trichoderma* retain over 90% germination after 5 years of storage, compared to 60% for conventionally frozen spores. However, lyophilization requires specialized equipment and is more costly, making it less accessible for small-scale applications.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the impact of freezing on spore viability is crucial for industries such as agriculture, food preservation, and biotechnology. For example, farmers storing fungal biocontrol agents like *Trichoderma* must ensure proper freezing protocols to maintain efficacy against soil pathogens. Similarly, laboratories preserving fungal cultures for research should monitor freezing conditions to avoid contamination or loss of viability. By tailoring freezing methods to specific fungal species and employing protective measures, stakeholders can maximize spore survival and functionality, ensuring reliable outcomes in both applied and experimental settings.

Directly Inoculating Agar with Spores: Best Practices and Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Cryopreservation Techniques: Methods to preserve fungal spores at ultra-low temperatures for research and agriculture

Fungal spores, with their remarkable resilience, can survive harsh conditions, but preserving them for long-term research and agricultural applications requires more than nature’s design. Cryopreservation, the art of freezing biological material at ultra-low temperatures, emerges as a critical technique. By plunging spores to temperatures below -130°C, often in liquid nitrogen (-196°C), their metabolic activity halts, effectively suspending them in time. This method ensures genetic stability, prevents degradation, and allows for the storage of diverse fungal species for decades, safeguarding biodiversity and enabling consistent access for scientific and agricultural endeavors.

The process begins with spore preparation, a step as crucial as the freezing itself. Spores must be cleaned to remove contaminants and suspended in a cryoprotectant solution, typically containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations of 5-10%. This solution prevents ice crystal formation, which can rupture cell membranes. The suspension is then loaded into cryovials, sealed to avoid contamination, and gradually cooled using controlled-rate freezers. A cooling rate of 1°C per minute is standard, ensuring spores acclimate without shock. Once cooled, vials are plunged into liquid nitrogen for long-term storage, where spores remain viable for years, if not decades.

Despite its effectiveness, cryopreservation is not without challenges. Thawing, for instance, requires precision to avoid damaging spores. Rapid warming in a 40°C water bath for 1-2 minutes is recommended, followed by immediate transfer to recovery media. Post-thaw viability checks are essential, with germination rates often assessed on agar plates. Researchers must also consider the species-specific tolerance of fungi to cryoprotectants and freezing protocols. For example, some species may require lower DMSO concentrations or alternative cryoprotectants like glycerol to maintain viability.

Cryopreservation’s applications are vast, particularly in agriculture, where fungal strains are harnessed for biocontrol, fermentation, and crop improvement. Preserved spores of *Trichoderma* species, for instance, can be revived to combat soil-borne pathogens, reducing reliance on chemical pesticides. In research, cryopreserved fungal libraries serve as genetic reservoirs, enabling studies on mycoremediation, drug discovery, and evolutionary biology. The technique also supports conservation efforts, preserving endangered fungal species for future reintroduction or study.

In conclusion, cryopreservation is a powerful tool for preserving fungal spores, bridging the gap between immediate needs and long-term goals. By mastering its techniques and addressing its challenges, scientists and agriculturalists can unlock the full potential of fungi, ensuring their availability for generations to come. Whether for research, conservation, or practical applications, the ultra-cold storage of fungal spores is a testament to human ingenuity in harnessing nature’s wonders.

Do Carnivorous Plants Produce Spores? Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$151.99 $219.99

Ecological Significance: Role of freezing in spore dispersal and survival in cold environments

Freezing temperatures, often seen as harsh and limiting, play a pivotal role in the life cycle of certain fungal species, particularly in cold environments. Many fungi have evolved mechanisms to not only survive but also exploit freezing conditions for spore dispersal and long-term survival. For instance, some fungal spores enter a state of cryopreservation, where metabolic activity is drastically reduced, allowing them to endure subzero temperatures for extended periods. This adaptation is crucial in polar regions, alpine zones, and other cold ecosystems where freezing is a persistent environmental factor.

Consider the process of freeze-thaw cycles, a common phenomenon in cold environments. When water freezes, it expands, creating cracks in soil, rock, and plant material. As temperatures rise and ice melts, fungal spores trapped within these cracks are released, dispersing more effectively than in static conditions. This natural mechanism enhances spore distribution, increasing the likelihood of colonization in new areas. For example, *Mortierella alpina*, a fungus found in alpine soils, relies on freeze-thaw cycles to disperse its spores, ensuring its survival in harsh mountain environments.

From an ecological perspective, freezing acts as a selective pressure, favoring fungi with robust spore structures and adaptive strategies. Spores with thick cell walls or those containing cryoprotectants, such as glycerol or trehalose, are better equipped to withstand freezing. These adaptations not only ensure survival but also contribute to the fungi’s role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability. In permafrost regions, for instance, fungal spores can remain dormant for centuries, only to revive when thawed, highlighting their resilience and ecological importance.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. Understanding how fungal spores survive freezing can inform the development of cold-resistant crop strains or preservation techniques for microbial cultures. For gardeners in cold climates, incorporating fungi like *Trichoderma* into soil amendments can enhance plant health, as these fungi thrive in freezing conditions and suppress pathogens. Similarly, researchers studying Antarctic fungi have identified enzymes that function at low temperatures, offering potential biotechnological advancements in cold-active processes.

In conclusion, freezing is not merely a challenge for fungal spores but a critical ecological driver in cold environments. By leveraging freeze-thaw cycles, developing cryotolerance, and exploiting unique dispersal mechanisms, fungi ensure their survival and contribute to the resilience of cold ecosystems. This understanding underscores the importance of studying fungal adaptations in extreme conditions, offering insights into both ecological dynamics and practical applications.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Vomiting? Understanding the Health Risks

You may want to see also

Species Variability: Differences in freezing resistance among fungal species and their adaptations

Fungal species exhibit remarkable variability in their resistance to freezing, a trait that significantly influences their survival in cold environments. This variability is not random but reflects specific adaptations that allow certain fungi to thrive where others cannot. For instance, psychrophilic fungi like *Cristalosporyidium arcticum* have evolved to produce antifreeze proteins that prevent ice crystals from forming within their cells, enabling them to survive temperatures as low as -20°C. In contrast, mesophilic fungi such as *Aspergillus niger* lack these proteins and are more susceptible to freezing damage, typically surviving only down to -5°C. Understanding these differences is crucial for applications in agriculture, food preservation, and biotechnology, where fungal resilience to cold can be harnessed or mitigated.

To explore these adaptations, consider the role of cellular composition in freezing resistance. Fungi with higher concentrations of glycerol, a cryoprotectant, can withstand freezing better than those without. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* increases glycerol production in response to cold stress, reducing intracellular ice formation and maintaining membrane integrity. This mechanism is not universal, however; some fungi rely on trehalose, a disaccharide that stabilizes proteins and cell structures during freezing. *Neurospora crassa*, for instance, accumulates trehalose to protect its cells, allowing it to survive freezing temperatures that would destroy less-adapted species. These biochemical strategies highlight the diversity of fungal responses to cold and underscore the importance of species-specific adaptations.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in the agricultural sector, where freezing-resistant fungi are used to protect crops from cold damage. For example, inoculating plant roots with *Trichoderma harzianum*, a fungus tolerant to freezing, can enhance crop resilience by promoting nutrient uptake and reducing frost-induced stress. Conversely, understanding the vulnerabilities of pathogenic fungi like *Botrytis cinerea*, which is less resistant to freezing, can inform the development of targeted biocontrol strategies. Farmers can exploit this weakness by applying fungicides during cold periods when the pathogen is most susceptible. Such targeted approaches minimize chemical use while maximizing efficacy, aligning with sustainable agricultural practices.

A comparative analysis of fungal spores further reveals how structural adaptations contribute to freezing resistance. Thick-walled spores, such as those of *Cladosporium* species, provide physical protection against ice damage, while thin-walled spores of *Penicillium* are more vulnerable. Additionally, melanin pigmentation in spore walls, observed in *Alternaria alternata*, acts as an antioxidant and insulator, reducing cellular damage during freezing. These structural differences explain why some fungal species dominate cold environments, while others are confined to temperate zones. By studying these traits, researchers can predict fungal distribution patterns and develop strategies to manipulate fungal populations in various ecosystems.

In conclusion, the variability in freezing resistance among fungal species is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. From biochemical cryoprotectants to structural spore adaptations, these mechanisms enable fungi to colonize diverse habitats, including the harshest cold environments. For practitioners in agriculture, biotechnology, and ecology, understanding these adaptations offers practical tools to enhance fungal benefits or mitigate their harms. Whether protecting crops from frost or preserving food through fungal biocontrol, the key lies in leveraging species-specific traits to achieve desired outcomes. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also empowers us to apply it effectively in real-world scenarios.

Can Rain Bring Mold Spores Indoors Through Open Windows?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungal spores can freeze, especially when exposed to temperatures below their freezing point. However, many fungal spores are highly resistant to freezing and can survive in frozen conditions for extended periods.

Freezing can reduce the viability of some fungal spores, but it does not always kill them. Many fungal spores have adaptations that allow them to survive freezing temperatures, such as producing protective compounds or entering a dormant state.

Fungal spores can survive in a frozen state for years or even decades, depending on the species and environmental conditions. Some spores have been found viable after being frozen for thousands of years in permafrost.

Freezing can temporarily halt the spread of fungal spores by immobilizing them in ice, but once temperatures rise, the spores can become active again. Freezing is not a reliable method for controlling fungal spore dispersal in most environments.