Glomeromycota, a diverse group of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, play a crucial role in plant nutrition by forming symbiotic relationships with plant roots. These fungi are known for their unique life cycle and specialized structures, but one question that often arises is whether they produce flagellated spores. Unlike some other fungal groups, such as Chytridiomycota, which are characterized by flagellated zoospores, Glomeromycota lack flagellated structures in their life cycle. Instead, they reproduce through asexual spores called chlamydospores and rely on hyphal growth for dispersal and colonization of plant roots, making them distinct in their reproductive strategies within the fungal kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Flagellated Spores | No, Glomeromycota do not produce flagellated spores. |

| Type of Spores | Asexual spores (chlamydospores and spores in vesicles) and zygospores. |

| Mode of Reproduction | Primarily asexual through vegetative spores; sexual reproduction via zygospores. |

| Motility | Spores are non-motile; lack flagella or other motility structures. |

| Habitat | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, primarily found in soil. |

| Symbiotic Relationship | Form mutualistic relationships with plant roots (arbuscular mycorrhiza). |

| Cell Wall Composition | Primarily composed of chitin, unlike flagellated fungi which often have cellulose. |

| Phylum | Glomeromycota (formerly Zygomycota). |

| Ecological Role | Enhance nutrient uptake (e.g., phosphorus) in plants. |

| Flagellated Structures | Absent in all life stages. |

Explore related products

$17.97 $29.95

What You'll Learn

- Glomeromycota spore structure: Do they possess flagella or other motility structures for movement

- Flagellated spores in fungi: Are flagella common in fungal spores, including Glomeromycota

- Glomeromycota reproduction methods: How do they disperse spores without flagella

- Comparison with flagellated fungi: How do Glomeromycota differ from fungi with flagellated spores

- Evidence of flagella in Glomeromycota: Is there any research indicating flagellated spores in this group

Glomeromycota spore structure: Do they possess flagella or other motility structures for movement?

Glomeromycota, a diverse group of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, play a crucial role in plant nutrition by forming symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Their spores are key to their life cycle, serving as dispersal units and survival structures. However, unlike some fungal groups, Glomeromycota spores lack flagella or other motility structures. This absence is a defining characteristic, as flagella are typically found in zoospores of water molds or certain lower fungi, enabling movement in aquatic environments. Glomeromycota, being primarily soil-dwelling, rely on passive dispersal mechanisms, such as attachment to soil particles or transport by soil organisms, rather than active movement.

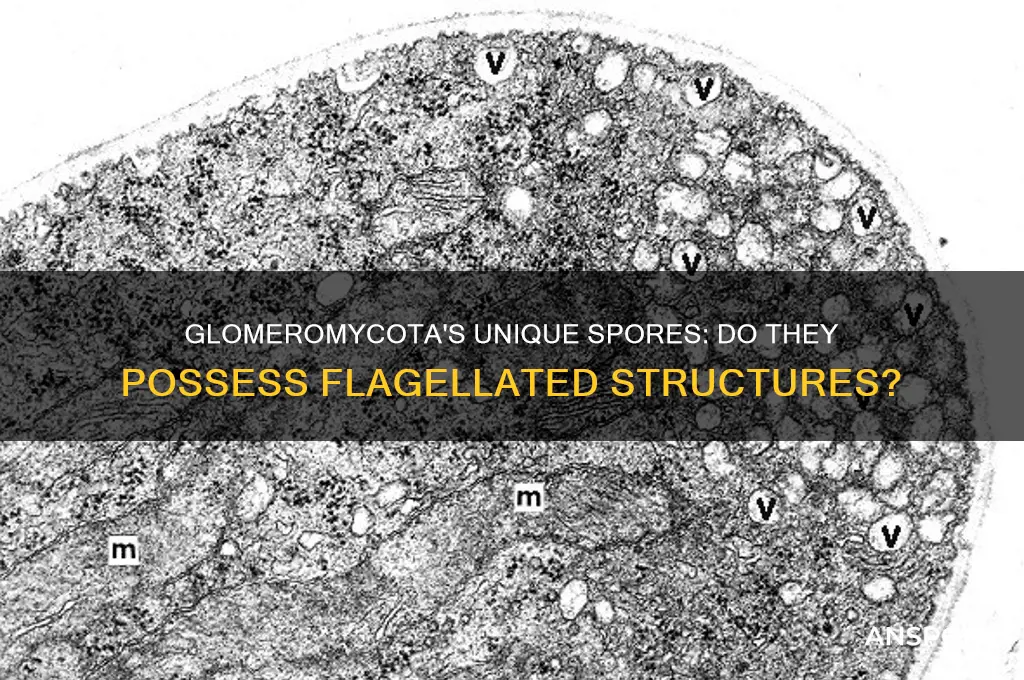

Analyzing the spore structure of Glomeromycota reveals a thick, resilient cell wall composed of chitin and other complex polymers, which protects the spore from harsh environmental conditions. This wall is often ornamented with ridges, spines, or reticulations, which may aid in attachment to soil or plant roots but do not facilitate motility. Internally, the spore contains lipid droplets and glycogen reserves, which support germination and early hyphal growth upon favorable conditions. The absence of flagella aligns with their ecological niche, as soil habitats do not require active swimming mechanisms for spore dispersal.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the lack of motility structures in Glomeromycota spores is essential for agricultural and ecological applications. For instance, when inoculating soils with these fungi to enhance plant growth, knowing their passive dispersal nature emphasizes the need for careful placement near plant roots. Techniques such as mixing spores into the rhizosphere or using carrier materials like peat can improve colonization success. Additionally, this knowledge informs conservation strategies, as protecting soil integrity and minimizing disturbance are critical for maintaining Glomeromycota populations.

Comparatively, the absence of flagella in Glomeromycota spores contrasts sharply with fungi like Chytridiomycota, which produce flagellated zoospores for aquatic dispersal. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptation of Glomeromycota to terrestrial environments, where water-based motility is unnecessary. Instead, their spores are designed for longevity and resistance, enabling survival in nutrient-poor soils for extended periods. This adaptation underscores their role as keystone species in soil ecosystems, facilitating nutrient cycling and plant health.

In conclusion, Glomeromycota spores are structurally specialized for survival and passive dispersal rather than active movement. Their lack of flagella or motility structures is a testament to their evolutionary success in soil habitats, where resilience and attachment mechanisms outweigh the need for mobility. For practitioners in agriculture, ecology, or mycology, this knowledge is invaluable for optimizing the use of these fungi in soil management and plant health strategies. By focusing on their unique spore characteristics, we can better harness their potential in sustainable agricultural practices and ecosystem restoration.

Download Spore Creature Creator for Free: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Flagellated spores in fungi: Are flagella common in fungal spores, including Glomeromycota?

Fungi exhibit remarkable diversity in their reproductive strategies, yet flagellated spores are notably rare within the kingdom. Most fungal spores are non-motile, relying on wind, water, or vectors for dispersal. Flagella, the whip-like structures enabling movement, are predominantly found in certain fungal groups, such as the Chytridiomycota, often referred to as chytrids. These fungi are considered the most primitive due to their retention of flagellated zoospores, which swim through aquatic environments to locate suitable substrates. This contrasts sharply with the majority of fungi, including Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which produce non-motile spores adapted for aerial dispersal.

Glomeromycota, a phylum of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), presents an intriguing case in this context. These fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake, but their reproductive structures lack flagella. Glomeromycota produce thick-walled spores that are resistant to environmental stresses, ensuring long-term survival in soil. These spores are passively dispersed through soil disturbances, root growth, or animal activity. The absence of flagella in Glomeromycota aligns with their ecological niche, where motility is less critical than durability and persistence in soil environments.

The rarity of flagellated spores in fungi, including Glomeromycota, underscores the evolutionary trade-offs between motility and other adaptations. Flagella require energy to produce and maintain, making them advantageous in aquatic or moist environments where movement enhances survival. In contrast, fungi in terrestrial ecosystems, such as Glomeromycota, prioritize spore robustness and longevity over motility. This distinction highlights how fungal reproductive strategies are finely tuned to their habitats, with flagella being a specialized trait rather than a common feature.

For researchers and enthusiasts studying fungal biology, understanding the distribution of flagellated spores provides insights into evolutionary relationships and ecological roles. Chytridiomycota’s flagellated zoospores, for instance, reflect their aquatic ancestry, while Glomeromycota’s non-motile spores exemplify adaptations to soil-dwelling lifestyles. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing conditions for fungal cultivation and managing soil health in agriculture, where AMF play a critical role in plant nutrition. By focusing on these specific traits, one can better appreciate the functional diversity within the fungal kingdom.

In summary, flagellated spores are uncommon in fungi, confined primarily to groups like Chytridiomycota, while most fungi, including Glomeromycota, lack this feature. This disparity reflects evolutionary adaptations to distinct environments, with motility favored in aquatic settings and durability prioritized in terrestrial ecosystems. For those working with fungi, recognizing these patterns aids in identifying species, understanding their ecological roles, and applying this knowledge in fields such as agriculture and conservation.

Can Marijuana Spores Trigger Hives? Exploring the Allergic Reaction Link

You may want to see also

Glomeromycota reproduction methods: How do they disperse spores without flagella?

Glomeromycota, a diverse group of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, lack flagellated spores, a feature common in many other fungal groups. This absence raises the question: how do they manage to disperse their spores effectively? The answer lies in their unique reproductive strategies, which rely heavily on their symbiotic relationships with plants and environmental factors. Unlike flagellated spores that swim through water, Glomeromycota spores are dispersed through soil, plant roots, and external agents, ensuring their survival and propagation.

One of the primary methods of spore dispersal in Glomeromycota is through mycorrhizal networks. When these fungi colonize plant roots, they form extensive hyphal networks that connect multiple plants. Spores are produced within these networks and can be transported from one plant to another, either through the soil or via root-to-root contact. This internal dispersal mechanism is highly efficient, as it leverages the existing fungal-plant symbiosis. For example, when a plant dies or sheds its roots, the spores embedded in the soil are released, ready to colonize new hosts. Gardeners and farmers can enhance this process by ensuring healthy soil conditions, such as maintaining organic matter and avoiding excessive tilling, which disrupts hyphal networks.

Another critical dispersal method is external agents, particularly soil organisms and water. Earthworms, insects, and other soil fauna inadvertently carry spores on their bodies as they move through the soil. Additionally, water runoff during rainfall or irrigation can transport spores to new locations. This passive dispersal is particularly effective in agricultural settings where water management practices, such as contour plowing or terracing, can be optimized to facilitate spore movement. For instance, planting cover crops with deep root systems can improve soil structure, aiding both water infiltration and spore dispersal.

A lesser-known but fascinating method involves spore attachment to plant seeds. Some Glomeromycota spores adhere to the surface of seeds, allowing them to be dispersed along with the plant. When the seed germinates in a new location, the fungus colonizes the emerging seedling, establishing a new mycorrhizal association. This strategy is particularly advantageous for plants in nutrient-poor soils, as the fungus enhances nutrient uptake. Farmers can capitalize on this by using inoculated seeds or ensuring that seed-cleaning processes do not remove beneficial fungal spores.

Despite their lack of flagella, Glomeromycota have evolved sophisticated dispersal mechanisms that capitalize on their symbiotic lifestyle and environmental interactions. Understanding these methods not only sheds light on their ecology but also provides practical insights for agriculture and ecosystem management. By fostering conditions that support mycorrhizal networks, external agents, and seed-spore associations, we can enhance soil health and plant productivity, demonstrating the importance of these fungi in sustainable practices.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Vegetable Gardens? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.25 $11.99

Comparison with flagellated fungi: How do Glomeromycota differ from fungi with flagellated spores?

Glomeromycota, a unique group of fungi, stand apart from their flagellated counterparts in several key ways. Unlike fungi such as Chytridiomycota, which produce motile spores equipped with flagella for dispersal in aquatic environments, Glomeromycota rely on a fundamentally different strategy for survival and propagation. Their spores are non-motile, lacking flagella entirely, and are instead dispersed through soil or via their symbiotic relationships with plant roots. This distinction highlights a profound adaptation to terrestrial ecosystems, where water-dependent motility is less advantageous.

Consider the structural and functional implications of this difference. Flagellated fungi, like Chytrids, invest energy in producing and maintaining flagella, which require complex molecular machinery for assembly and operation. In contrast, Glomeromycota allocate resources toward forming robust, thick-walled spores capable of enduring harsh soil conditions and long periods of dormancy. This trade-off reflects their ecological niche: while flagellated fungi thrive in wet, transient habitats, Glomeromycota excel in stable, nutrient-rich soil environments where longevity and resilience are paramount.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences has implications for agricultural and ecological management. For instance, farmers cultivating mycorrhizal crops benefit from Glomeromycota’s ability to form symbiotic associations with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake and stress tolerance. In contrast, flagellated fungi like Chytrids are often studied for their role in aquatic ecosystems or as pathogens, such as *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, which causes chytridiomycosis in amphibians. Tailoring strategies to manage these fungi requires recognizing their distinct dispersal mechanisms and ecological roles.

A comparative analysis reveals that the absence of flagellated spores in Glomeromycota is not a limitation but a specialization. Their success lies in forming extensive hyphal networks that facilitate nutrient exchange with host plants, a feature absent in flagellated fungi. This symbiotic lifestyle reduces the need for motile spores, as spore dispersal often occurs via plant roots or soil adhesion. Conversely, flagellated fungi rely on water currents to disperse their spores, limiting their effectiveness in dry or terrestrial environments.

In conclusion, the divergence between Glomeromycota and flagellated fungi underscores the evolutionary ingenuity of these organisms. By abandoning flagellated spores, Glomeromycota have carved out a niche as essential symbionts in terrestrial ecosystems, while flagellated fungi remain tied to aquatic or damp habitats. This comparison not only enriches our understanding of fungal diversity but also informs practical applications in agriculture, conservation, and disease management.

Can Spores Harm Green Giant Arborvitae? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Evidence of flagella in Glomeromycota: Is there any research indicating flagellated spores in this group?

Glomeromycota, a diverse group of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, play a crucial role in plant nutrient uptake and soil ecosystems. Despite their ecological significance, the presence of flagellated spores in this group remains a topic of scientific inquiry. Flagellated spores are typically associated with aquatic fungi and some zygomycetes, but their existence in Glomeromycota has not been conclusively established. This raises the question: Is there any research indicating flagellated spores in Glomeromycota?

To address this, it is essential to examine the reproductive structures of Glomeromycota. These fungi primarily produce thick-walled spores, known as chlamydospores, which are asexual and lack flagella. Their life cycle is predominantly subterranean, with spores dispersed through soil or via plant roots. While flagella are common in zoospores of other fungal groups, such as Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota rely on hyphal growth and root colonization for propagation. This fundamental difference in reproductive strategy suggests that flagellated spores may not align with their evolutionary adaptations.

Research to date has not provided evidence of flagellated spores in Glomeromycota. Studies employing electron microscopy and molecular techniques have focused on spore morphology, wall composition, and genetic markers, yet none have identified flagellar structures. For instance, a 2018 study published in *Fungal Biology* analyzed spore ultrastructure in *Rhizophagus irregularis* and confirmed the absence of flagella. Similarly, genomic analyses of Glomeromycota have not revealed genes associated with flagellar assembly, further supporting the hypothesis that these fungi lack flagellated spores.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the absence of flagellated spores in Glomeromycota has implications for their cultivation and application in agriculture. Since these fungi do not produce motile spores, their dispersal relies on physical vectors like soil movement, root growth, or inoculum addition. Farmers and researchers can optimize mycorrhizal inoculation by focusing on soil conditions and root contact rather than expecting spore motility. This knowledge also underscores the importance of preserving soil integrity to maintain Glomeromycota populations.

In conclusion, current evidence strongly indicates that Glomeromycota do not possess flagellated spores. Their reproductive biology, supported by morphological and genetic studies, aligns with a flagella-free lifestyle. While this finding may seem definitive, ongoing research in fungal evolution and ecology could reveal unexpected adaptations. For now, the absence of flagella in Glomeromycota remains a key characteristic distinguishing them from other fungal groups, shaping their ecological role and practical applications.

Exploring Genetic Diversity: Are Spores Unique or Identical?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Glomeromycota do not have flagellated spores. They produce spores that are non-motile and lack flagella.

Glomeromycota spores disperse through passive mechanisms such as water, wind, soil movement, or via animal vectors, as they lack the ability to move on their own.

No, Glomeromycota belong to a group of fungi that do not produce flagellated spores. Flagellated spores are typically found in other fungal groups, such as Chytridiomycota.

Glomeromycota produce thick-walled, non-motile spores called chlamydospores or zygospores, which are adapted for survival in soil environments.