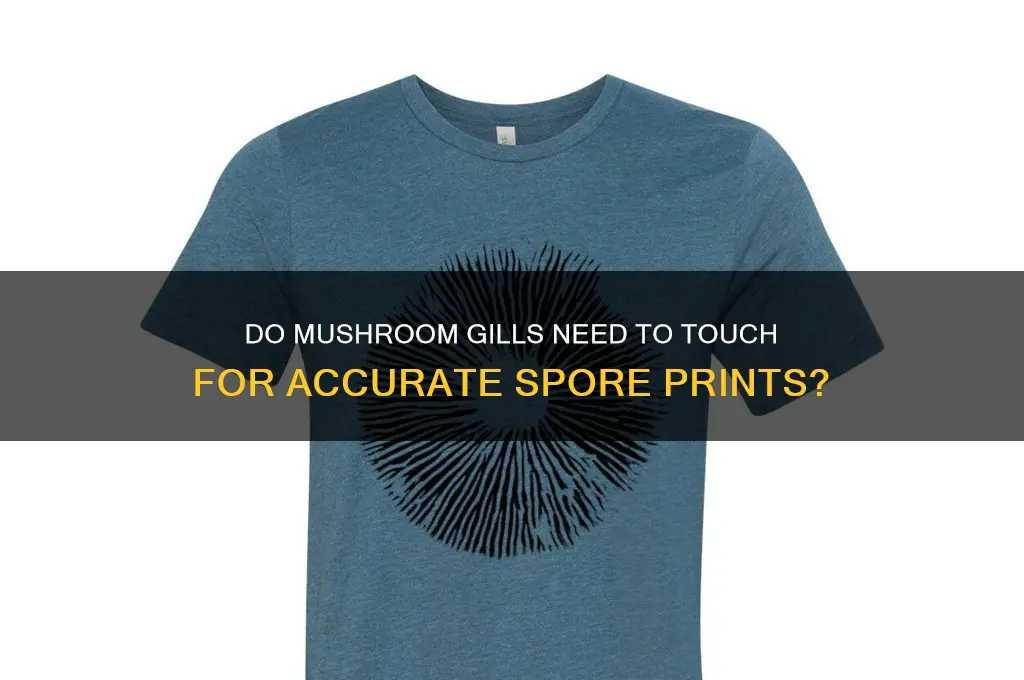

When exploring the process of creating a spore print from mushrooms, a common question arises: do the gills of the mushroom need to touch the surface to obtain a clear and accurate print? Spore prints are a valuable tool for identifying mushroom species, as they reveal the color and pattern of the spores. To create a spore print, the cap of the mushroom is typically placed gills-down on a piece of paper or glass, allowing the spores to fall naturally. While direct contact between the gills and the surface is ideal for a clean and complete print, it is not always necessary. Even if the gills do not touch the surface perfectly, spores can still be released and collected, though the resulting print may be less defined or contain gaps. Therefore, while optimal contact enhances the quality of the spore print, it is not a strict requirement for successful spore collection.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do gills need to touch for spore print? | No, gills do not need to physically touch to obtain a spore print. |

| Spore print method | Place the mushroom cap gills-down on paper or glass for several hours. |

| Spore release mechanism | Spores are released naturally through gravity and air currents. |

| Gills proximity requirement | Gills should be close to the surface but do not need to touch directly. |

| Optimal conditions | Moist environment, stable temperature, and minimal air disturbance. |

| Common misconceptions | Gills must touch the surface or be pressed for spore release. |

| Spore print color | Varies by mushroom species, used for identification. |

| Time required | Typically 4-8 hours, depending on species and conditions. |

| Surface suitability | White paper or glass for clear spore print visualization. |

| Preservation | Spore prints can be preserved by covering with a transparent material. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Print Basics: Understanding the process and purpose of creating spore prints from mushrooms

- Gill Structure Role: How gill spacing and structure affect spore release and print clarity

- Touch vs. Proximity: Do gills need to physically touch, or is close proximity enough

- Species Variations: Differences in spore print methods across mushroom species and gill types

- Alternative Techniques: Methods to obtain spore prints without requiring gill contact

Spore Print Basics: Understanding the process and purpose of creating spore prints from mushrooms

Creating a spore print is a delicate process that hinges on the precise placement of a mushroom cap, gills facing downward, onto a surface. The question of whether gills must touch the surface directly is critical. In reality, the gills don’t need to physically touch the paper or glass for a successful print; spores are released passively through gravity. However, ensuring the gills are close enough to allow spores to fall without obstruction is key. A gap between the gills and the surface can lead to scattered or incomplete prints, so using a spacer like a thin wire mesh or a breathable material can optimize results while maintaining airflow.

The purpose of a spore print extends beyond mere aesthetics; it’s a diagnostic tool for mushroom identification. Spore color, a defining characteristic of many species, can differentiate between edible and toxic varieties. For instance, the spores of *Amanita muscaria* are white, while those of *Coprinus comatus* are black. To create a print, place a mature mushroom cap on a piece of dark and light paper (to account for spore colors that may blend into one surface) and cover it with a bowl to maintain humidity. After 6–24 hours, carefully remove the cap and examine the spore deposit. This method is particularly useful for foragers and mycologists who rely on precise identification.

While the process seems straightforward, several factors can influence the outcome. Humidity, temperature, and the mushroom’s maturity play significant roles. Spores are more likely to drop in a humid environment, so covering the setup is essential. If the mushroom is too young or overripe, spore release may be minimal or inconsistent. For best results, select a specimen with fully developed gills and a cap that lies flat when placed on the surface. Avoid handling the gills directly, as oils from your skin can contaminate the print.

Comparing spore printing to other identification methods highlights its practicality. DNA analysis, while definitive, is costly and time-consuming, whereas spore prints can be made with minimal equipment. Microscopic examination of spores is more detailed but requires specialized tools. Spore prints strike a balance, offering a quick, low-cost method that provides critical color and pattern data. For beginners, mastering this technique is a foundational skill in mycology, bridging the gap between casual observation and scientific study.

In practice, spore printing is both an art and a science. Patience and attention to detail are paramount. For educators or hobbyists, involving children or groups in the process can foster an appreciation for fungi’s role in ecosystems. Practical tips include labeling prints immediately with the mushroom’s collection date and location, storing them in airtight containers, and using glass slides for long-term preservation. By understanding the nuances of spore printing, enthusiasts can unlock a deeper connection to the fungal world, one print at a time.

Did Spore Ever Get Good? Revisiting the Game's Legacy

You may want to see also

Gill Structure Role: How gill spacing and structure affect spore release and print clarity

The spacing between gills in fungi is a critical factor in spore release and print clarity. Gills that are too close together can hinder spore dispersal, as the spores may clump or fail to detach efficiently. Conversely, overly spaced gills can result in uneven spore deposition, leading to a patchy or indistinct print. Optimal gill spacing allows spores to drop freely and uniformly, creating a clear, consistent print. For example, species like *Coprinus comatus* have widely spaced gills that facilitate rapid spore release, while *Agaricus bisporus* has closely packed gills that require more time for spores to accumulate. Understanding this relationship helps mycologists predict spore print quality based on gill structure.

To maximize spore print clarity, consider the gill structure of the fungus in question. For species with dense gills, such as *Panaeolus cyanescens*, place a glass or plastic cover over the cap to create a humid microenvironment, encouraging spores to drop without clumping. For fungi with open gill structures, like *Amanita muscaria*, a simple sheet of paper or foil placed beneath the cap often suffices. Patience is key; allow 6–12 hours for spore deposition, as rushed attempts can yield incomplete prints. Always handle the mushroom gently to avoid disturbing the gill arrangement, which could skew the results.

Gill structure also influences the practicality of obtaining a spore print. Thin, fragile gills, as seen in *Marasmius* species, may break or collapse under slight pressure, making it difficult to position the cap for printing. In such cases, use a fine mesh or thin fabric as a support layer to maintain gill integrity. For mushrooms with decurrent gills, like *Lactarius* species, ensure the entire gill surface contacts the substrate to capture spores that drop along the stem. Observing these structural nuances can transform a failed attempt into a successful, high-clarity print.

Comparing gill structures across species highlights their evolutionary adaptations for spore dispersal. For instance, the tightly packed gills of *Boletus edulis* are designed for slow, controlled spore release, reflecting its habitat needs. In contrast, the widely spaced gills of *Schizophyllum commune* enable rapid dispersal in windy environments. By studying these adaptations, mycologists can infer ecological roles and improve spore print techniques. For hobbyists, recognizing these patterns ensures a more informed and effective approach to spore collection.

Instructive tips for optimizing spore prints based on gill structure include selecting mature specimens with fully developed gills, as immature fungi may produce incomplete prints. For species with crowded gills, lightly brushing the cap with a soft brush can dislodge spores without damaging the structure. When working with delicate gills, use a magnifying glass to inspect the arrangement before proceeding. Documenting gill spacing and print outcomes for different species creates a valuable reference for future attempts. With practice, the interplay between gill structure and spore release becomes intuitive, enhancing both accuracy and efficiency in mycological studies.

Do Cordyceps Release Spores? Unveiling the Fungal Reproduction Mystery

You may want to see also

Touch vs. Proximity: Do gills need to physically touch, or is close proximity enough?

The debate over whether gills must physically touch to produce a spore print hinges on the delicate interplay between fungal anatomy and environmental conditions. Spore prints are created when spores are released from the gills and deposited onto a surface, forming a pattern that aids in mushroom identification. While direct contact between gills and the substrate seems intuitive, mycologists argue that proximity alone can suffice under optimal conditions. For instance, placing a mature cap gill-side down on a piece of paper or glass for 6–12 hours often yields a clear print, even without pressure. This suggests that spore release is primarily driven by gravity and air currents rather than physical contact.

To maximize success, consider the humidity and maturity of the mushroom. Spores are more readily released when the gills are fully developed and the environment is humid, typically around 60–70% relative humidity. If proximity alone isn’t yielding results, gently pressing the cap onto the substrate for 2–3 hours can enhance spore deposition. However, avoid excessive force, as it may damage the gills and distort the print. For beginners, using a glass surface allows for easy observation of spore release without disturbing the setup.

A comparative analysis reveals that while touch can expedite the process, it isn’t strictly necessary. In controlled experiments, spore prints from caps placed in close proximity (1–2 mm from the substrate) showed no significant difference in clarity or completeness compared to those from caps pressed directly onto the surface. This finding challenges the traditional method, suggesting that proximity, combined with adequate time and humidity, is sufficient for most species. Exceptions may include mushrooms with dense or recessed gills, where slight pressure aids spore release.

Practically, this insight simplifies the spore printing process, especially for field mycologists. Instead of meticulously pressing caps onto paper, collectors can place mushrooms gill-side down in a humid container, such as a sealed plastic bag or box with a damp paper towel, and wait for spores to settle naturally. This method preserves the mushroom’s structure while ensuring a high-quality print. For educational purposes, demonstrating both touch and proximity methods can illustrate the adaptability of fungal spore dispersal mechanisms.

In conclusion, while physical touch can enhance spore print clarity, close proximity is often enough to achieve reliable results. By focusing on environmental factors like humidity and gill maturity, enthusiasts can streamline the process without compromising accuracy. Whether for identification or artistic purposes, understanding the touch vs. proximity dynamic empowers mycologists to work more efficiently and effectively with fungal specimens.

Can Civilizations Thrive in Claimed Systems Within Spore's Universe?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

$16.99

Species Variations: Differences in spore print methods across mushroom species and gill types

Mushroom enthusiasts often wonder whether gills must touch to produce a viable spore print, but the answer varies dramatically across species. For instance, Agaricus bisporus (the common button mushroom) has densely packed, free gills that release spores efficiently even without direct contact. In contrast, Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushrooms) have broad, decurrent gills that benefit from slight pressure to ensure complete spore discharge. Understanding these species-specific traits is crucial for accurate identification and cultivation.

When attempting spore prints, the gill structure dictates the method. Lactarius species, with their forked or interconnected gills, often require a flat surface to capture spores effectively, as their unique gill arrangement can hinder spore release if not properly supported. Conversely, Amanita species, known for their crowded, free gills, typically produce clean prints when placed gill-side down on paper or glass. The key is to observe whether the gills are attached (adnate), free, or decurrent, as these characteristics influence spore dispersal patterns.

For species with delicate or widely spaced gills, such as Marasmius oreades (the fairy ring mushroom), a lighter touch is necessary. Placing a glass over the cap without pressing can help capture spores without damaging the fragile structure. In contrast, Boletus species, which lack gills entirely and instead have pores, require a different approach altogether—spore prints are replaced by spore deposits collected by placing the pore surface on a dark background for several hours.

Practical tips for species-specific spore printing include using a moisture-resistant surface for Coprinus comatus (the shaggy mane), as its gills deliquesce quickly, and applying gentle pressure for Stropharia rugosoannulata (the wine cap stropharia) to ensure all spores are released from its crowded gills. Always consider the mushroom’s age; younger specimens may not yet have mature spores, while older ones might have already dropped them. Tailoring your approach to the species and gill type ensures success and preserves the mushroom’s integrity for further study.

Troubleshooting Tips: Why You Can't Create an EA Account for Spore

You may want to see also

Alternative Techniques: Methods to obtain spore prints without requiring gill contact

Obtaining a spore print without direct gill contact is not only possible but also a valuable skill for mycologists and enthusiasts alike. Traditional methods often involve placing the mushroom cap gills-down on paper, but this can be limiting, especially with delicate or irregular specimens. Alternative techniques offer precision, reduce contamination risk, and accommodate a wider range of mushroom species. By exploring these methods, you can expand your mycological toolkit and improve the accuracy of your spore prints.

One effective alternative is the spore syringe method, which bypasses gill contact entirely. To create a spore syringe, sterilize a syringe and needle, then carefully suspend the mushroom cap in a sterile container with a small amount of distilled water. After 24–48 hours, the spores will have fallen into the water, creating a spore suspension. Draw this liquid into the syringe, and you have a concentrated spore sample ready for study or cultivation. This method is particularly useful for species with fragile gills or those that decompose quickly.

Another technique involves using adhesive tape to capture spores indirectly. Place a piece of transparent tape over the gills, gently press to ensure contact, and then carefully lift the tape. The spores will adhere to the tape, which can then be transferred to a glass slide or paper for examination. This method is non-invasive and ideal for preserving the mushroom’s structure, though it may yield fewer spores compared to traditional prints. It’s best suited for detailed microscopic analysis rather than large-scale spore collection.

For those seeking a hands-off approach, the spore deposition chamber offers a controlled environment. Place the mushroom cap inside a sealed container with a piece of glass or paper positioned below the gills. Over time, spores will naturally fall onto the surface, creating a clean print. This method minimizes contamination and works well for mushrooms with dense or recessed gills. However, it requires patience, as spore deposition can take several hours to complete.

Each of these techniques has its strengths and limitations, but together they provide a versatile toolkit for spore collection. Whether you’re working with fragile specimens, conducting detailed research, or simply exploring alternative methods, these approaches ensure that gill contact is no longer a requirement for successful spore prints. By mastering these techniques, you can enhance your mycological practice and unlock new possibilities in fungal study.

From Barracks to Beliefs: Can Military Cities Transform into Religious Hubs?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, gills do not have to touch for a spore print to be successful. The spores are released from the gills and can fall onto the surface below without direct contact.

Yes, you can still get a spore print even if the gills are spaced apart. Spores are dispersed through the air and will settle on the surface beneath the mushroom.

The distance between gills does not significantly affect the quality of a spore print, as long as the spores are allowed to fall freely onto the surface.

No, it is not necessary to press the gills together. Simply placing the mushroom cap gills-down on a surface is sufficient for spores to drop.

No, a spore print will not fail if the gills are not touching the surface. Spores are lightweight and will naturally fall onto the surface below without direct contact.